In an introduction to the 1997 volume Itsuko Hasegawa: Selected and Current Work 1976-1996, the critic and photographer Kōji Taki attempts a reading of Itsuko Hasegawa’s Shonandai Cultural Center. Seeking to situate and consolidate Hasegawa’s architectural production up to that point, Taki remarks “I believe Shonandai was just an initial step: for Hasegawa herself, for defining community participation in architecture, and for developing a method of making public architecture.”1 Thematically focusing on participation and the social, Taki treads well-established territory when discussing a public project like Shonandai. Having worked extensively with community members in developing the program and design of Shonandai, Hasegawa’s approach was a surprisingly fresh one for 1980s Japanese public architecture.2 As her first major public project, Taki was eager to support and advance Hasegawa’s career (Taki was always a booster for architecture’s critical darlings).3 In his evaluation of the project, however, Taki situates Hasegawa’s work in a somewhat puzzling light: “The possibility of a latent femininity in the city came up in our discussions at that time, but to avoid confusion with more limited issues of feminism, the discussion gradually came closer and closer to issues of locality. Shonandai is public architecture, a community center for a particular place.”4

It is unclear what Taki might mean by a “latent femininity in the city,” and what Hasegawa’s response was to this discussion. Framed as an insight quickly tabled for later, this moment in the text points to a longer-standing dialogue between Hasegawa and Taki over the presence and nature of feminism within Hasegawa’s architectural practice. What begins to emerge in this extended conversation and debate, which stretched over the course of a few decades, is a disparate set of narrative desires. One involves a push for clarity, a sense of progression that positions each step as a sequel to the previous one, building towards a point of arrival. Another approaches the circumstantial and the accidental as key elements of architectural production, a means of incorporating what has heretofore been excluded. That the former appears as “masculine” and the latter “feminine” is, for Taki, a critical distinction. For Hasegawa, it is utterly beside the point (and perhaps even fundamentally misleading). Hasegawa’s architectural narrative can be understood as a form of meander, a narrative form that, according to author and critic Jane Alison, “hint[s] at structures inside them rather than an arc, structures that create an inner sensation of traveling toward something and leave a sense of shape behind.”5 In other words, what might be “latent” for Taki is potent for Hasegawa. This “latent femininity in the city” is an emergent strand of design thinking that has been ever-present yet elided by the desire for a clearer narrative of descent and lineage within Japanese architectural history. Such a desire has hounded Hasegawa’s career from the start, though not without utility.

Itsuko Hasegawa’s early career united two distinct lineages of midcentury Japanese architecture: the large-scale, experimental work of Kiyonori Kikutake, for whom Hasegawa worked from 1964-69, and the more human-scaled work of Kazuo Shinohara, for whom Hasegawa worked throughout the 1970s. Navigating the conflicting design ideologies of Kikutake and Shinohara would inform many of Hasegawa’s subsequent designs, influencing her approach to broad conceptions of the “social” in architecture and design. While still a student at Kanto Gakuin University, Hasegawa was directly recruited by Kikutake to help with a model for the Kyoto International Convention Center competition. She worked closely with Kikutake, primarily on large-scale projects as part of the “kata” team, which did the main design work in his office.6 She left Kikutake’s lab after five years, as her proclaimed interests in a more human-scaled and human-focused design agenda led her to explore residential design with Kazuo Shinohara at the Tokyo Institute of Technology.7

Upon joining Shinohara’s lab, Hasegawa quickly became an essential member of his practice, in no small part because Hasegawa held a “first class” architecture license in Japan, which allowed her to oversee more structurally complex projects, while Shinohara did not.8 Though initially drawn to Shinohara’s office for his approach to traditional domestic architectural design, Hasegawa’s incorporation into the studio coincided with Shinohara’s turn away from such practices. As Hasegawa would later explain about her time in his office, “In a way, I learned from Shinohara by negative example.” Hasegawa would note how Shinohara

was, in a sense, a great architect, but many problems arose because of his attitude towards the more mundane aspects of practice. He would nonchalantly say things like, “It isn’t necessary to see the site, it isn’t necessary to listen to the client.” He started to ignore all the normal requirements of the design process in order to turn the architecture into an artwork.9

Such a move towards architecture-as-art-object would galvanize Hasegawa’s contrary position to see architecture as a conscientious practice of designing lived experience and of using design to “provide amenity for modern life.”10 Despite such an ideological clash of positions, Hasegawa continued to work in Shinohara’s office throughout the 1970s. It was here that she would meet Kōji Taki, who was hired by Shinohara to photograph his recently completed houses.

It was also within Shinohara’s office that Hasegawa began to implicitly construct her narrative as a woman in architecture in Japan. Common within university-based design labs in Japan (like that of Shinohara) is the seminar, an intellectual complement to studio-based design work. Hasegawa notes how Shinohara’s seminar made

it clear that architecture is an intellectual construct, based on rigorous theoretical and philosophical reasoning; that buildings are engineering structures that must be reconciled with social behaviors, and that there are severe obstacles in the way of women who decide to practice architecture. At the conclusion of the seminar, Shinohara said to me, “To become an architect, you must have the ability to first become masculine, and then once again become feminine.”11

The misogynistic absurdity of Shinohara’s conception of what it takes to become an architect reinforces a linearity akin to a bildungsroman, a prototypical literary narrative of personal growth only conceivable through a masculine lens. As an “intellectual construct” focused on a process of reasoned philosophical reconciliation, there is simply no space—literally and figuratively—in Shinohara’s view for a woman to progress in architecture as a woman. While the “feminine” may be an ultimate point of arrival, for Shinohara, it cannot be a point of departure.

But why be a point at all? The linearity of this conception of architectural development directly connecting one’s personal identity to one’s practice of architecture appeared anathema to Hasegawa and thoroughly inessential, which she indicates by stating that she “didn’t try to change anything” about herself in the face of Shinohara’s directives.12 Perhaps unsurprisingly, Hasegawa’s refusal to “change” to fit within the limited parameters laid out by Shinohara coincided with her first small, solo-authored houses. Founding her own practice in 1978 (before leaving Shinohara’s office in 1979), Hasegawa’s meandering path towards professional independence perhaps inadvertently reinforced Shinohara’s developmental narrative through the dialectical relationship it presupposes: that an act of synthesis—between the philosophical “rigor” of a masculinist studio culture and the more meditative single-authored houses of her early practice—is necessary in order to “arrive” at the feminine in architecture.

This supposed dialectical movement and its embedded dichotomies were turned on their head by Hasegawa in a 1985 special issue of the magazine SD (Space Design) dedicated to her work. Published in advance of her winning the Shonandai design competition, the special issue was devoted primarily to her residential work, with commentaries by the likes of Taki, the architectural historian Hajime Yatsuka, and fellow architects Makoto Kikuchi and Hiroyuki Suzuki. While many of these commentaries appear in both English and Japanese, the volume also includes a long, untranslated interview with Hasegawa titled “Kenchiku no feminizumu,” which can be translated as “Architectural Feminism,” though one could also render it in the more possessive phrasing of “The Feminism of Architecture.”13 In the English-language table of contents to the special issue, however, the editors chose to translate the title as “The Feminine Touch in Architecture.” Though Hasegawa’s interlocutor is unnamed in the issue itself, she would later note that the longform interview was between her and Taki, and that it was his choice to render the English translation in this way.14 Covering a wide range of topics related to her work throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, Taki’s line of questioning evolves into a discussion of Hasegawa’s generation (including Toyo Ito and Arata Isozaki) and its specific contributions to architectural discourse. In asking about the connection between modern architecture and the seemingly “ad-hoc” nature of Hasegawa’s approach to design, her response is the first moment when we start to see her formulate and name a specific idea of feminist architectural praxis. She connects this to a form of “pop reason” that, as an intellectual counterpoint to the philosophically-inclined design principles typical of midcentury Japanese design, focuses on a more on-the-ground or “popular” understanding of design’s potentialities.

If we take an ad-hoc approach to designing, treating design as being on the same level as an event, I am always afraid that we are creating a particular solution when we respond to too many contingencies and filter out the coincidental. But should we be conventionally inventive, or work with pop reason? While I think there is a very delicate issue involved in trying to find the state of the modern architect in the latter, I would like to work without being bound by preconceived notions of what an architect should be. I think it is safe to say that I am situated in the latter category [working with pop reason].15

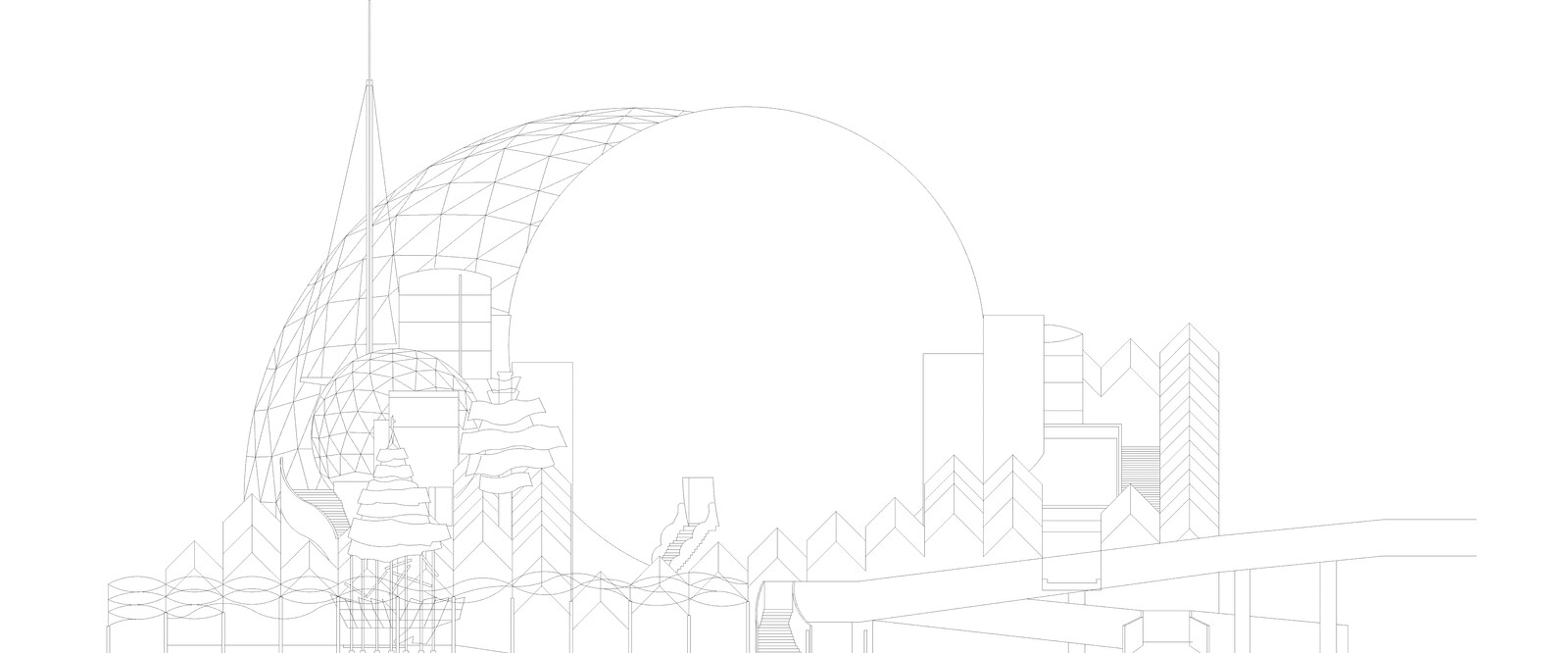

The desire to “not be bound by preconceived notions of what an architect should be” marks Hasegawa’s departure from the narrative projections of Shinohara as well as from the probing idealization of Taki. One of the earliest examples of this departure arises in Hasegawa’s design for the Shonandai Cultural Center. Taking up a full city block in Fujisawa City, the project boasts a planimetric abundance of forms and juxtapositions: sinuous lines of circulation move around a gridded plaza broken by a jagged artificial stream. A monumental sphere partially sunk at the northern end of the complex holds a cavernous theater and performance space, while a second sphere just to its south floats above the central plaza, a globe emblazoned with a map of the world on its metal exterior. A continuous collection of peaked square tubes bundle together along the perimeter like a palisade, a stark contrast to the variety of flows and forms contained within. When collapsed in elevation, architectural forms and textures overlap and interpenetrate like on a city skyline; juxtaposition and coincidence manifest the ad-hoc at the urban scale, condensed into a single architectural complex yet still monumental.

This play of “coincidences” and the “coincidental” derived from an engagement with the “ad-hoc approach to designing” marks Hasegawa’s clear departure from the intellectualized and object-driven styles of Kikutake and Shinohara. Through documentation, fieldwork, and conversation with the oft un-consulted future users of the center, Hasegawa’s design methodology works beyond the “rigorous theoretical and philosophical reasoning” expounded in the studio and seminars of Shinohara as well as the strident partitioning of activity in Kikutake’s lab; both studios maintained a unidirectional and almost teleological progression in design thinking. No less rigorous for its embrace of the coincidental, Hasegawa’s departure from the strictures of her previous employers expands the possibilities of architectural production beyond the supposed divisions of gendered sensibility. Continuing in the SD conversation, Hasegawa remarks:

I am convinced that there is something to be found in the process of expanding the scope of architecture in the process of picking up the accidental. The theoretical reason that architecture has demanded in the past, which requires engineering and philosophical rigor of thought, has eliminated many things. If pop reason is based on a broad base that seeks to incorporate what has been excluded, then when I talk about this in the architectural world, as usual, I am not taken seriously, and I am perceived as feminine. Feminine, however, has nothing to do with the issue of gender division.16

This is an early moment in Hasegawa’s self-theorization when she explicitly challenges the dominant “philosophical” characterization of architectural production in Japan in the 1970s and 1980s—which her former employers Kikutake and Shinohara were instrumental in helping to form. It is also a moment when she directly responds to the “feminine perception” mapped onto her career by the likes of Shinohara. What Hasegawa formulates as “feminine” is a new working method that she positions primarily in contradistinction to the dominant discussions of architecture taking place among her peers.

Such a method is also a direct indictment of postwar Japanese architectural design practice, which embraced a triumphalist narrative of perseverance and overcoming in the face of devastating urban destruction. Given her position as one of the few prominent female architects at the time, Hasegawa was constantly called upon as a kind of standard-bearer on behalf of her gender, an uncomfortable position but also seemingly an inescapable one. As Hasegawa notes further along in SD:

I have never paid much attention to this issue [of being a female architect]; however, it seems to be argued in various quarters that the failure of the “male principle,” which has been the foundation of culture since the dawn of time, has emerged at an impasse in modern culture, and that another principle, let us call it the “female principle,” is needed to counter it, rather than adding a role or raising an issue based on sex discrimination. It seems that there is a meaningful argument to be made for this new principle. From such an argument, it would seem that the fundamental principles of our culture, thought, and architecture have always been based on the “male principle,” but that a different “female principle” is needed from now on. If we extend the concept to this point, “feminine principles,” “feminine things,” or feminism may all have meaning in architecture as well.17

An act of reclamation as well as repositioning, Hasegawa’s answer here, in 1985—a year before winning the competition for Shonandai—offers a clear hint at what her agenda for an “architectural feminism” would come to contain. Despite its admonitions, Hasegawa’s demarcation of gendered “principles” may seem to reproduce the misogynistic divisions of the field. However, unlike the processional qualities described by Shinohara requiring one to “first become masculine,” Hasegawa’s principles set each on an equal footing, making gender a productive method rather than an ontological hurdle.

The preconceptions of architecture Hasegawa associates with the “male” principle are picked up by Taki as well. In fact, Taki remarks on this quality in Hasegawa’s work as early as 1977, in a critique of her early houses, focusing in particular on her House in Yaizu 2. A striking triangular form, clad in metal with incidental interruptions to the facade by intersecting lines of structural bracing and window placements, Taki highlights the ways in which an embrace of the incidental can come to form a new set of interpretive meanings for a work of architecture. In this critique, which was republished as part of the 1985 SD special issue, Taki writes:

It seems certain that Hasegawa does not think of architecture as the introspective expression of the architect nor as completed, symbolic space. Her perception of the nature of things and space appears to be shaped by the understanding of architecture as something neutralized, set apart from human emotions as is a machine, and not tainted with a priori meanings or preconceptions … The absence of symbolism is based on the perception that the themes of architecture have an inextricable diversity. At this point in time, the basis of Hasegawa’s architecture, although it has yet to become sufficiently organized and ordered, can perhaps be described as the plurality of architecture.18

Taki’s comment highlights the relationship between the seemingly “simplistic form” of a triangular facade (or the “pop reasoning” of her Shonandai Cultural Center) and the deep well of metaphorical associations that such strategically simple forms bring into being as the key means of understanding Hasegawa’s architectural production. This essential lack of “fixedness” in the meaning of an architectural work pushes against the dominant and domineering agenda of the time in Japan, and works to formulate a new methodological agenda for the “feminine” in architecture. Taki continues by noting how

Only one very simple and definite method is visible in each of her works. Simplistic form on the visible level and a jumble of diversity and plurality on the abstract level interact in her designs. This intriguing relationship between the visible and abstract in her work makes it necessary to strive for an appreciation of what is not directly apparent in her architecture.19

It is here that Hasegawa’s activated form of “architectural feminism” comes into view, as opposed to the applied “feminism of architecture” (or “a touch of the feminine,” as SD put it). It is not a characteristic that would be innate and therefore exclusive to female-sexed architects, but is instead a methodological approach and architectural agenda that no longer requires some kind of gendered “movement” of masculinization. The constricted dialogue that Hasegawa had seen forced on her by the likes of Shinohara, Taki, and others unspools into a multiplicity, a meandering process emerging from direct engagement with the ad-hoc and coincidental potentials of a design rather than the directed (and expected) progression espoused by others. While the “latent femininity” in the city that Taki identifies with Hasegawa’s approach is one that he works to position in a dialogical “clash” with masculine, traditional, “architecture,” Hasegawa disregards that confrontational stance, seeing the “feminine” position as a meaningful complement rather than a direct competitor. What is “latent,” then, is also accessible and inviting. The story is instead about another mode of architectural production, one that can be taken up by anyone; it isn’t about gender or sex, but methodology and approach. Instead of accepting the oppositional dialogue of a masculine/feminine approach that must synthesize (and more likely sublimate) the latter in order to fully become the former, Hasegawa embraces the meandering possibility of conversation and narrative evolution. Why choose when one can simply do?

Kōji Taki, “Introduction: Form and Program,” in Itsuko Hasegawa: Selected and Current Works by Itsuko Hasegawa, trans. Michel van Ackere (Mulgrave, Australia: Images Publishing Group, 1997), 11.

Thomas Daniell and Itsuko Hasegawa, “Itsuko Hasegawa in Conversation with Thomas Daniell,” AA Files 72 (2016): 24.

Up until winning the open Shonandai Cultural Centre competition, Hasegawa’s independent architectural practice had been gaining increasing recognition for a series of private homes in Japan throughout the 1970s.

Taki, “Introduction: Form and Program,” 11.

Jane Alison, Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative (New York: Catapult, 2019), 20.

Kikutake famously divided his studio into three teams—“ka,” “kata,” and “katachi”—which might best be translated as “force, gesture, and shape.” Daniell and Hasegawa, “Itsuko Hasegawa in Conversation with Thomas Daniell,” 24.

Itsuko Hasegawa, “My Work of the Seventies,” SD (Space Design) 247, no. 4 (April 1985): 108–9.

Based on the 1950 Kenchikushi Law in Japan, architectural licensing is divided into first and second classes (as well as a mokuzo kenchikushi designation that was added in 1984 specifically for wood construction). A first class architect license in Japan allows one to oversee both design and construction on reinforced concrete and steel structures, as well as any large-scale public buildings and places of assembly such as schools, hospitals, theaters, etc. With much of Shinohara’s work in the early 1970s being in wood, a first class license wasn’t necessary.

Daniell and Hasegawa, “Itsuko Hasegawa in Conversation with Thomas Daniell,” 25.

Daniell and Hasegawa, “Itsuko Hasegawa in Conversation with Thomas Daniell,” 25.

Daniell and Hasegawa, “Itsuko Hasegawa in Conversation with Thomas Daniell,” 25.

Daniell and Hasegawa, “Itsuko Hasegawa in Conversation with Thomas Daniell,” 25.

“Special Feature: Itsuko Hasegawa,” SD (Space Design) 247, no. 4 (April 1985).

Daniell and Hasegawa, “Itsuko Hasegawa in Conversation with Thomas Daniell,” 34.

Kōji Taki and Itsuko Hasegawa, “An Interview with Itsuko Hasegawa: Architectural Feminism,” SD (Space Design) 247, no. 4 (April 1985): 80. Translation by the author.

Taki and Hasegawa, “An Interview with Itsuko Hasegawa, ” 80–81. Translation by the author.

Taki and Hasegawa, “An Interview with Itsuko Hasegawa, ” 81–82. Translation by the author, emphasis his.

Kōji Taki, “Diversity and Simplicity (1977),” SD (Space Design) 247, no. 4 (April 1985): 92–93.

Taki, “Diversity and Simplicity (1977),” 96–97.

Asian Feminist Architectural Possibilities is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and Ruo Jia, supported by Pratt Institute.