Sri Lanka is … an interesting example of a society in which women were not subjected to harsh and overt forms of oppression, and therefore did not develop a movement for women’s emancipation that went beyond the existing social parameters. It is precisely this background that has enabled Sri Lanka to produce a woman prime minister, as well as many women in the professions, but without disturbing the general patterns of subordination.1

—Kumari Jayawardena

The close interplay between feminism and nationalism in Sri Lanka and in Asia more generally has been explored astutely in Kumari Jayawardena’s foundational text, Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World (1986), as well as in Neloufer de Mel’s Women and the Nation’s Narrative: Gender and Nationalism in Twentieth Century Sri Lanka (2001), among others. These texts outline the specifics of this dynamic in the Sri Lankan context, where women have, in some respects, played pioneering roles, but where an oppressive heteropatriarchy dominates society more generally. Within this milieu, unpacking feminist possibilities within the discipline of architecture is tricky business.

The practice of architecture—a field that intersects spheres of capital and social politics—inevitably creates interactions that are defined by gender, class, and in twentieth century Sri Lanka, caste.2 This entrenchment in social and economic structures, however, means that architectural agency affords real possibility for engaging with feminist thinking. Discourse on feminism in architecture in Sri Lanka, even Asia, is necessarily a conversation around elective affinities, like its interplay with decolonization, nation-building, and identity. Three female figures in the recent architectural history of Sri Lanka offer insight into these elective affinities, which are heightened in specific contexts. Each of these women are exceptional rather than typical, but their stories as architects are filled with insight into potential and possibility in both architecture and feminism.

Minnette de Silva (1918–98), Vasantha Jacobsen (neé Chandraratna, 1932–present), and Shanti Jayewardene (1947–present) each navigated the discipline of architecture in Sri Lanka in unique and pioneering ways.3 One of the first Asian women to be elected as an associate of RIBA, Minnette de Silva was also the first Asian architect to participate in CIAM and one of the founding members of MARG, the Indian Art Magazine first published in 1946. Vasantha Jacobsen was one of the earliest graduates of the newly founded Architecture Course at the University of Ceylon in 1961, who obtained a scholarship to study at the Royal Danish Academy and later became the project architect for the New Sri Lankan Parliament designed by Geoffrey Bawa’s practice.4 And Shanti Jayewardene is one of the earliest historians and critics of contemporary Sri Lankan architecture who has written on imperial Sri Lankan and Indian subjects since the early 1980s.

Apart from Minnette, whose mother (Agnes Nell) was a keen advocate for women’s rights, and whose sister (Anil) is the subject of a chapter in Neloufer de Mel’s Women and the Nation’s Narrative, Vasantha and Shanti do not identify or ground their work in explicitly feminist discourse. When I broached this topic with Shanti, she remarked: “How can we talk about feminism when you see the status of women in this country?”5 We go on to discuss what it means to be a woman living in Sri Lanka—an experience that often includes harassment and subjugation, especially in semi-urban and rural parts of the island. I am wary of using the story of a few to suggest possibilities for the many, especially when it must be acknowledged that all three of these figures had privileged access to education and a more liberal urban social milieu than the average Sri Lankan woman. But each of these women, through their engagement with practice, wrestle with the patriarchy inherent to architecture within the region and thus have valuable stories to tell. Their encounters with nation-building and the project of decolonization must also then navigate possibilities for charting a practice against the grain.

Education and Decolonization

Shanti Jayewardene gained her architectural education in Sri Lanka and in the UK. She was one of a handful of women of color studying at the time at the Architectural Association in London, then at the Bartlett, UCL, and later at the University of Oxford, where she obtained her doctorate.6 When she began her master’s studies at the Bartlett in 1982, the course had just been established as “The History of Modern Architecture,” now the MA in Architectural History. “For my dissertation I explored [Geoffrey] Bawa’s work from the pioneering theoretical position my tutors, historians Adrian Forty and Mark Swenarton, were developing. For them, architecture was not simply about style, or what architects say, rather it was an activity engaging broader material and intellectual processes. It was logical that their theoretical stance would eventually push me to look at empire, though they did not quite intend it.”7

As a student in the UK, Shanti was able to marry historiographic methodologies with insights gained from having grown up in Sri Lanka, and having worked there on archaeological and architectural projects. She worked with the State Engineering Corporation from 1974 to 1975, and in 1983, when she returned to Sri Lanka to conduct research for her master’s, she was detained for a year due to the outbreak of the civil war. During this time, Shanti worked as project architect on the Abhayagiri Monastic Complex Excavation Project, alongside Professor Senake Bandaranayake, archaeology consultant to Surath Wickramasinghe Associates.8 The client, the Central Cultural Fund, enlisted architects to work with the archaeological teams on these projects. It was a defining experience for Shanti, providing an opportunity to engage deeply and directly with Sri Lanka’s own architectural history.

Following her master’s, Shanti was invited by her tutors to teach on a new master’s course at UCL titled “Architecture in Development,” where she was asked to “teach what you know.” While Shanti’s work in Sri Lanka coupled with her life in the UK equipped her to teach these courses, the request also highlights the ways in which the former colonizing nations continued their control over pedagogic development. In Shanti’s view, the knowledge of modern architecture in the former colonies was almost unknown in the UK, where she felt it was marginalized and separated from imperial architecture in Britain and mainstream knowledge making. She was recruited to teach architecture to students mostly from the developing world rather than in the mainstream history or architecture courses. The role of both race and gender in this marginalization is open to speculation.

Around the same time, in 1986, she was invited to contribute to the Aga Khan Trust for Culture’s journal Mimar: Architecture in Development. The journal sought a break with the Western dominance of popular architectural literature, and she collaborated with the American historian Brian Brace Taylor as a contributing editor. The research and writing for this work pressed Shanti to reflect on her own position, which simultaneously absorbed and rejected the intellectual imbalance instituted in the colonial era.

Her experience at Anuradhapura also grounded her approach to Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa’s work. In her 2017 book Geoffrey Manning Bawa: Decolonizing Architecture, Shanti combined her master’s and doctoral research with Geoffrey Bawa’s work from a decolonial perspective that is rooted in a deep understanding of Sri Lanka’s history and architectural traditions.9 The publication paves a path for a history and theory of architecture in Sri Lanka that foregrounds historiography and offers a possibility for alternative understandings, including feminist histories. In approaching architecture through teaching, writing, editing, and research, Shanti navigated the imperialistic biases of architecture.

Dependability and Competency

Vasantha Jacobsen is one of the most enigmatic figures within Geoffrey Bawa’s practice, working for almost three decades at the firm, overseeing major projects like the New Sri Lankan Parliament as project architect, and yet barely leaving any traces of her presence. 10 The Geoffrey Bawa archives hold scarcely any material drawn or signed by her, whereas the work of some of her colleagues who worked for shorter periods at the firm can be amply traced. Understanding her role at the firm has been impressively difficult; she is mentioned by many but without anecdotes or details. A colleague and close friend of Vasantha, Anura Ratnavibushana, described her ability to get things done, her sense of humor and ready laugh, and her loyalty. Philip Fowler, who also worked at Geoffrey Bawa’s practice and was part of the parliament project team, remarked that Vasantha was “the most loyal subject in the kingdom of Bawa.”11 He elaborated: “Vasantha’s acute attention to detail and her ability to remember innumerable points to be discussed in large and complex projects, especially the parliament project where urgent decisions had to be made as many key materials and fixtures came from Japan, were integral to the success of these projects.”12

The particular strain of the parliament project was mentioned by David Robson, who notes that Vasantha’s hair grew from black to white in the three-year course of its construction.13 Following the project, both Vasantha and her husband Jakob, a devout Buddhist whom she met in Copenhagen, decided to ordain as Buddhist monks. Given the paucity of primary sources on Vasantha, it is not possible to arrive at any definitive conclusions about her motivations to pursue this path. But it is worth mentioning that the New Sri Lankan Parliament was completed in 1982, and in 1983 a pogrom following decades of ethnic unrest gave rise to a twenty-six-year-long civil war.

Vasantha was a figure whose commitment was to the work, and who left no traces except for the work itself. How many parliaments or buildings of national stature from the twentieth century had female project architects? Although her religious instincts were keen even when she left for Denmark,14 it is unclear what her opinions on feminism might have been. It is equally unclear what her beliefs around decolonization or nation-building were; the only fact we can reckon with is that the Sri Lankan Parliament building was fundamentally emblematic of these efforts.

The Sri Lankan Parliament was built on the heels of similar efforts in neighboring parts of South Asia, most famously Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh in India (inaugurated 1953) and Louis Kahn’s National Assembly Building in Bangladesh of 1982. In comparison to these projects, it is noteworthy that Sri Lanka’s parliament was designed by local architects. Three figures mentioned as architects on the building’s plaque are two men of Dutch Burgher and Muslim ancestry (Bawa) and Tamil ancestry (Poologasundram), and a Sinhala Buddhist woman (Jacobsen).

While the only one from that group of a majority ethnicity or religion, Vasantha was still one of only a few women architects in the country at the time. Her story is a testament to the fruits of hard work, of being dependable, or being loyal, of getting the work done. That she was also described as a “giggler” is poignant. History books abound with supporting characters to whom these qualities are ascribed. As the collective nature of architectural practice becomes more accepted, we might also recast these narratives to describe the intrinsic indispensability of such figures.

Archives and Biographies

Minnette de Silva’s practice of architecture was intertwined with defining a post-independence identity for the nation. Working in the immediately postcolonial moment (she would return from her studies in Bombay in 1948, the same year Sri Lanka gained independence from the British), her appreciation of craft and integration of art in her work, and the extension of her practice beyond building to include writing, editing, and teaching, suggests that Minnette was aware of feminist approaches to architecture, pushing against the mundane and mainstream understandings of what architecture might involve.

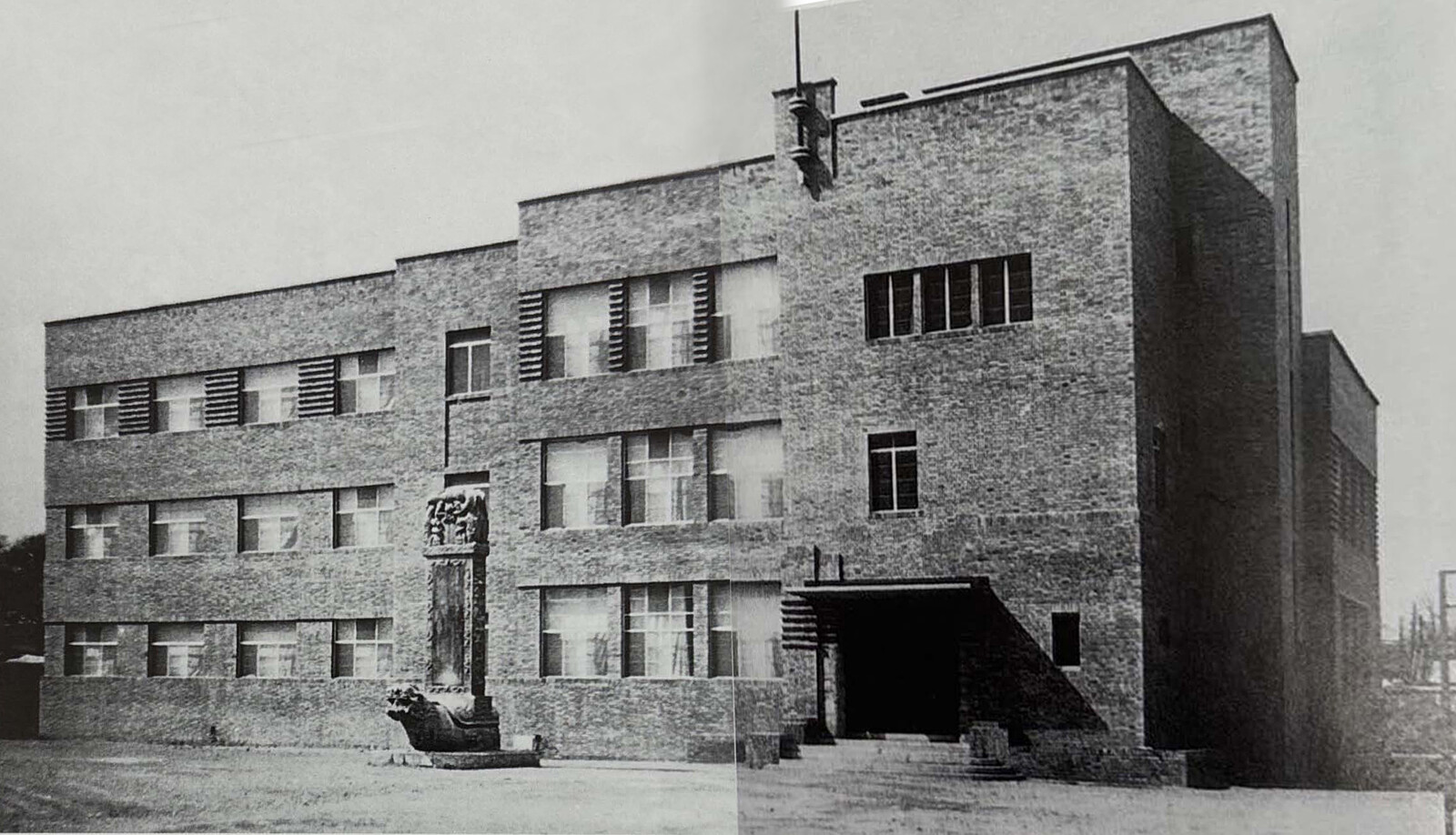

Writing on Minnette by those who knew her, often focuses on her image and personality, like Ulrik Plesner’s 2012 memoir, In Situ. A Danish architect who came to Sri Lanka in 1957 to assist Minnette on the Watapuluwa housing scheme, he left the practice after a year to work instead with Geoffrey Bawa. His memoir describes Minnette in uncharitable and misogynistic ways. An entire chapter is dedicated to this period with Minnette spelled incorrectly throughout as “Minette.” Ulrik writes, “Most importantly, I went to London to meet Minette [sic] de Silva, who was visiting her friend Lady Corea, the wife of the Ceylonese ambassador or ‘high commissioner’ there. Minette [sic] was good-looking, which was the most important thing, so I agreed in five minutes.”15 He describes the work he did at Minnette’s office with scarcely any engagement on the depth of her ideas or the vast network of creative forces in which she moved, but describes at length what he perceives as a lack of “charm.” [Image 5]

The fact that writers like Ulrik Plesner, who worked with Minnette and thus had rare insight into her practice, wrote so little about her work and ideas, makes Minnette’s decision to put her own monograph together before she died in 1998 even more valuable. In her book on Geoffrey Bawa, Shanti Jayewardene writes of Minnette, “Her buildings strove to synthesize European tropical modernist forms with indigenous craft decoration. Her pioneering role as an architect in decolonizing South Asia is not recognized.”16 The work to be done in terms of “recognizing” Minnette alluded to here also speaks to the fact that her estate, including archives and collections, does not have a clear or publicized beneficiary.

If Vasantha’s story is one where, apart from final outcomes, there are hardly any discernible traces within archives and other repositories, Minnette’s story tells us that it is equally fruitful to leave a web of objects which can be understood collectively. As described by Anooradha Siddiqi, “archival deficit is a familiar crisis in women’s histories or even art and architectural histories, yet, rather than impose a sense of loss and condemnation on the scene, I would insist that we follow [Antoinette] Burton’s sense of opportunity and shift the historiographical gaze towards alternate forms of intellectual and material productivity.”17 In understanding both the project of the archive and the project of architecture in Minnette’s work, we are led to look beyond the conventionally defined extents of these endeavors. We cannot rely on the few surviving buildings that still exist of hers. We are led instead to dwell deeply in the texts produced by Minnette, and the ideas and buildings recorded in these materials, to understand her work. This is an inherently feminist act, the occupation of spaces of the “other,” alongside those of convention, which push boundaries and expand disciplinary spheres.

There is intrinsic possibility—specifically feminist possibility—generated in the ways in which Minnette, Vasantha, and Shanti each navigated their professional paths. Their work pursues possibility within architecture, but the interwoven ties to education, the writing of history, creation of archives, and construction of buildings that architecture encompasses means that their practices had far-reaching, transdisciplinary impact. The absence of textual and material data uncovering these practices also necessitate feminist historiographies and other expansive methods to uncover and understand their work. Recognizing the elective affinities that define these efforts—nation-building, decolonization, and other endeavors—as resonant and amplifying, offers possibility for unpacking these histories and charting further possibility.

Kumari Jayawardena, “Women in Sri Lanka” in Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World (London: Verso, 2016), 136.

While Neloufer de Mel notes how caste impacted the perception of an architect like Minnette in the first half of the twentieth century, this author perceives caste oppression to be less pervasive than gender and class in more recent times.

Also known as Shanti Jayewardene Pillai.

More information on the history of formalized architectural training courses can be found via the University of Moratuwa website: ➝.

Author interview with Shanti Jayewardene, October 6, 2024, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Ibid.

Public discussion with Shanti Jayewardene, “Geoffrey Manning Bawa and Decolonizing Architecture,” (part of exhibition program Geoffrey Bawa: It is Essential to be There organized by the Geoffrey Bawa Trust), March 24, 2022, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Abhayagiri is a monastic site exceeding 200 hectares in Anuradhapura, in the North Central Province of the island, dating from 89 to 77 BCE. Although the monastery has not been occupied since the eleventh century, the stupa, which is the second largest in Sri Lanka, is still visited by pilgrims.

Shanti’s doctoral studies from 1998 unraveled the shared interface of imperial architectural knowledge making where British military engineers and Indian intellectuals met, in nineteenth-century South India. Her book, based on this research, Imperial Conversations: Indo-Britons and the Architecture of South India was published in Delhi in 2007 under the name Shanti Jayewardene Pillai.

Vasantha also produced some buildings through her own practice; for more information refer Lamahewa, Susil and Jamaldeen, Shahdia, “The Lady behind the Screen: Finding Vasantha Jacobsen” in The Architect, Volume 123, Issue 1, January 2024.

Author interview with Anura Ratnavibushana, October 31, 2024, Colombo, Sri Lanka; author interview with Philip Fowler, June 28, 2019, transcript, Oral Histories, Geoffrey Bawa Trust Archives, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Author interview with Philip Fowler, December 10, 2024, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

David Robson, Geoffrey Bawa: The Complete Works (London: Thames & Hudson, 2002). Note: neither Philip nor Anura were able to recall this particular detail in interviews with the author.

Author interview with Philip Fowler, December 10, 2024, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Ulrik Plesner, “Minette,” in In Situ (Copenhagen: Aristo, 2013), 55.

Shanti Jayewardene, “Ceylon: Colonial Modern Architecture and Independence, 1939…” in Geoffrey Manning Bawa: Decolonizing Architecture. (Colombo: The National Trust Sri Lanka, 2017), 81.

Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi “Crafting the archive: Minnette De Silva, Architecture, and History” in The Journal of Architecture, 22, no. 8 (2017). In Geoffrey Bawa: The Complete Works, David Robson also writes “Vasantha Jacobsen’s achievements have never been fully documented, and she deserves to be remembered alongside Minette {sic} de Silva as one of Sri Lank’s first women architects.” (pp. 266) Robson also acknowledges that “though she and Bawa were not the best of friends, there can be little doubt that de Silva’s early designs were an important influence for him.” (pp. 51).

Asian Feminist Architectural Possibilities is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and Ruo Jia, supported by Pratt Institute.