In 1952, Chinese architects Lin Huiyin and Liang Sicheng published a translation of Soviet architect Nikolai Voronin’s Rebuilding the Liberated Areas of the Soviet Union.1 In their foreword, Lin and Liang identified reconstruction (chongjian, 重建) and redesign (chongxin sheji, 重新设计) as the operable problematics for socialism both in China and beyond. German and Japanese invaders had destroyed the built environment, a material and physical register of the failure of early Soviet and Republican building practices to facilitate a society capable of withstanding the challenges of international forces of reaction. However, beyond the desire to build a stronger state, Lin and Liang realized that, even before the Japanese invasion, the Chinese landscape indexed and reinscribed the contradictory tendencies of capital that were at fault for the rise of fascism. Thus, if socialism were to succeed—both as a modernizing project aimed at urban development and as a political attempt to abolish past hierarchies—the environment would have to be simultaneously rebuilt and built anew.

While Lin and Liang’s translation was based on an English edition, Voronin’s contemporaneous works in Russian show a similar thinking around the twin problematics of re-building and building anew (rekonstruktsiya, реконструкция and vosstanovleniye, восстановление, literally “reconstruction” and “restoration”). Within this constellation, Lin, Liang, and Voronin reimagined the architect as a facilitator of new productive relations while grappling with the place of traditional aesthetics and their role in socialism. Could the socialist architect preserve classical Chinese and Slavic signifiers in the face of fascist attempts at cultural destruction, while also transforming them into constitutive parts of a more equitable economic system and a new experience of habitation by a burgeoning international subject? At stake in this question is the content of that socialist subject. Reading Lin and Liang through Voronin reveals two attempts to grapple with the role of reproductive and domestic labor in a moment of egalitarian transformation and collectivization. Their work thus provides a new locus for articulating a specific Asian feminism while also revealing blind spots in Marxian and Soviet economic accounts of reproduction.

Moreover, Lin and Liang’s particular work explores what it means to do translation as socialist praxis. Lin and Liang’s project of cultural reconstruction arose out of a critical engagement with Soviet theory and is undergirded by the philosophical and practical task of making foreign experiments speak to the reality of Chinese socialism qua a global project of world-making. Analyzing these texts in this way recontextualizes their discussion of national culture (minzu wenhua, 民族文化) as something profoundly radical and material: a new culture (xinwenhua, 新文化) for a socialist subject in the process of its coming into existence—one in need of a new built environment to both renew and reconstruct this subjectivity. These conclusions arose from Voronin’s own insistence that “the cities which have suffered from the temporary fascist occupation are, as it were, being born anew,” and thus the task of “restoration” was always-already a task of building the future, both physically and ideologically.2 I have chosen to translate the nexus of tasks comprising chongjian and vosstanovleniye as “renewal.” This was done in order to account for the breadth of their intervention beyond questions of technical construction implied by “reconstruction,” and to emphasize the new-ness and emancipatory vision of their design aspiration that, while nationally-defined, moved beyond the reactionary connotations implied in “restoring” the landscape to its former glory. Taking a hint from the Chinese word for “redesign” deployed by Lin and Liang (chongxin sheji, 重新设计, literally to “re-new design”), the English “renewal” represents an apropos yet self-contradictory signifier that gestures to the twin tasks of rebuilding infrastructure and envisioning a new environment beyond that practical necessity. Renewal also encapsulates these three thinkers’ commitment to making the cultural and aesthetic dimensions of historical design relevant to a new world. In the words of Voronin, “architects bear great responsibility to both history and future generations.”3

Looking at the work of these three architects through the lens of renewal shows the fraught task of thinking beyond capitalism. Indeed, their utopian project opened these thinkers to the trap of reifying immanent components of their semicolonial reality as natural facets of their respective nations. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Voronin’s identification of a transhistorical substrate of Russo-Slavic culture and perseverance, which in turn articulated his vision of peasant aesthetics. At the same time, socialist renewal reveals the productive possibilities of placing the immanent and the utopian in dialectical confrontation, as was the case with Lin, who, in both her co-authored translation with Liang and in other writings of the time, positioned Chinese culture (zhongguo wenhua, 中国文化) less as a fact of the past and more as a latent potential: a future-goal of equitable social relations uniquely conceivable from China’s position at the intersection of feudalism, imperialism, and communism, all shot through with patriarchy and in desperate need of feminist alternatives.

Actualizing this potential entailed another translation: from the plan to the environment. Whereas Voronin saw in the blank slate created by the Nazi’s systematic destruction the potential for a more efficient “return to normal economic and industrial life,” Lin grasped at a theoretical blank slate that had been created by a liquidation of the political powers representing the old society that freed cultural and historical signifiers from a system of oppression.4 Lin argued that this allowed the Chinese landscape to be rethought from the ground up—not just literally, but conceptually and socially, and in such a way as to subject social reproduction and domestic life to the same emancipation sought in the sphere of production.

Reviving this project of feminist possibility is also an intervention in the story of Lin Huiyin, whose later relegation to the role of cultural preservationist belies the sophistication and revolutionary dimension of “culture” in her body of thought. Indeed, positioning Lin as the defender of a timeless building tradition against the forces of modernization homogenizes the various political contexts within which she operated and drains her critiques of their specificity. This not only obfuscates the political agency she exerted within socialist state building, but also reenacts her real-world exclusion from the domain of politics, beginning with her exclusion from architectural education in the US and continuing all the way to her exclusion from city-planning decisions in the early years of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).5 Instead, the dearth of buildings designed by Lin can be read as indicative of a party bureaucracy that was exclusively male and only capable of imagining a male socialist subject triumphing over alienated economic relations, and thus incapable of actualizing or even conceptualizing Lin’s broader intervention outside of a reductive project of national renewal. In the face of mounting nationalism and imperial aggression perpetrated by the still male-dominated state bureaucracies of post-socialist Russia and China today, renewing this radical intervention and its vision of utopian world-making is more important than ever. It encourages us to remember the feminist potentialities overwritten by these structural conditions and to hold open the future for another subject in another built environment.

Revolutionary Rupture and Post-Socialist Translations

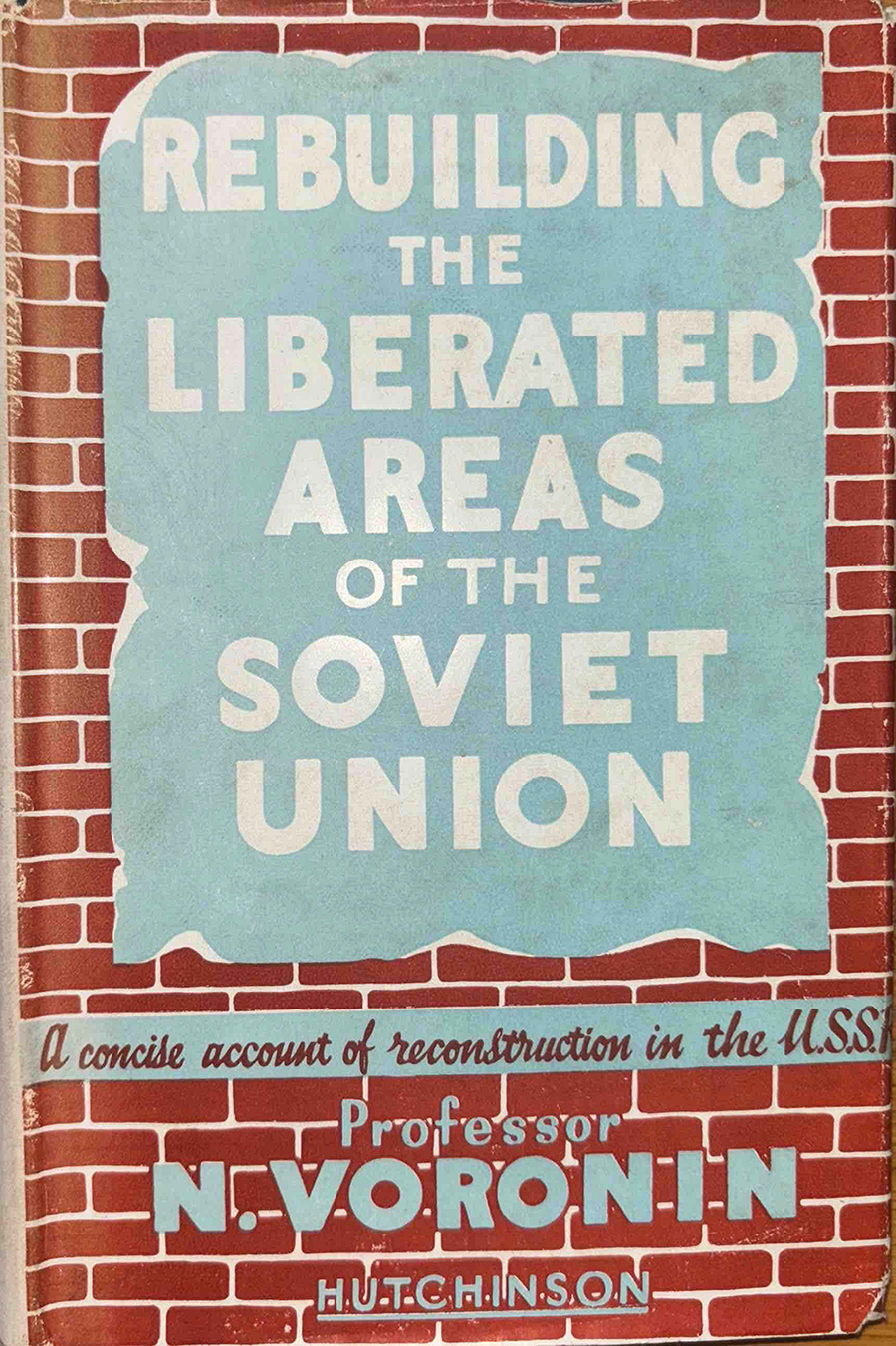

The Soviet architect and historian Nikolai Nikolayevich Voronin wrote Rebuilding the Liberated Areas of the Soviet Union between 1944-45. The text indexes a series of works presented to the All-Union Archaeological Conference in the spring of 1945, chiefly his “On the Organization and Legal Justification for the Protection and Study of Archaeological Monuments in the USSR,” published in the same year.6 This presentation represented a triumphant return for Voronin, who had been removed from his post at the Institute for the History of Material Culture of the USSR Academy of Sciences (IIMK) due to falling out of favor of his mentors M. N. Pokrovsky and M. M. Tsivibak.7 In the essay, Voronin decries the 1938 dissolution of the Committee on the Preservation of Monuments, which left monuments of classical Slavic architecture “without supervision to this day,” a warning that resonated with an intelligentsia freshly victorious in the “Great Patriotic War.”8 Moreover, the lessons learned through his excommunication, the dismantling of administrative bureaus, and his own experience of the war on the frontlines drew his attention not only to the “vulgar sociologism” of his earlier works, but also to the need for a more holistic understanding of cultural architecture.9 Thus, Rebuilding builds on the most activist and universal points of his previous works and compiles them for international export. As such, Rebuilding represents no one single extant Russian text. Likely compiled and translated by Soviet academics, it first appeared in English in London in 1945, for the modest price of ten shillings. Dutch, Italian, and Indian editions appeared shortly after.10

Looking at Rebuilding, we see Voronin’s attempt to rework a series of pre-war essays that, due to their lack of historical specificity, led to his fall from grace.11 However, this desire to revisit previous work was not merely an academic exercise, but an evolution of his political aims and practical responsibilities. Indeed, by 1944, Voronin was directly implicated in the task of rebuilding as a member of the Committee on Architecture, which was responsible for the restoration and preservation of national monuments, and as a member of the Academy of Architecture, whose vice president, Karo Alabyan, oversaw the restoration of Soviet towns.12 As such, Rebuilding was simultaneously practical and propagandistic. It sought to extol the “age-old architecture of the Russian people” alongside the necessity of “structural changes” to the pre-communist forms of Slavic architecture, such as the village, the farm, and the metropole.13

Similar to Voronin’s pre-war writing, Rebuilding identifies the village as the fundamental unit of Slavic social organization. Unlike his earlier work, however, Rebuilding’s conception of the village-form is notably articulated by Soviet collectivization as a progressive experiment in social organization, one which laid bare historical hierarchy and gendered violence that were themselves anchored to traditional modes of rural habitation. In other words, collectivization represented a political intervention not only in economic reproduction but also in social reproduction. In his own words, Voronin acknowledged that “the restoration of the villages destroyed by the Germans must reflect these tremendous economic and social changes which are the result of socialist reconstruction and collectivization of farming.”14

By positing the rural inhabitant as a political subject who must deconstruct the reproduction of authority, collectivization destabilized Voronin’s assumption of a passive peasant class. In past investigations, Voronin saw the sloboda (a type of colony of non-indentured artisans, whose Russian name means “freedom”) as the spatial domain of the “freed slave” (osvobozhdennykh rabov, освобожденных рабов).”15 However, the young architect took this feudal exception (the sloboda) and positioned it as a general, prehistoric entity wherein slaves found themselves liberated from chattel bondage only to be subjected to systems of authority and land management like the church and the estate. This transformed these settlements from sloboda into selo (or villages, село), wherein a hazy process of “feudalization” (feodalizatsii, феодализации) finally converted freed slaves into serfs (krepostnoy, крепостной). The Soviet art historian Sergey Bakhrushin published a critique of Voronin in which he argues that, in fact, the sloboda and the selo existed side by side, neither wholly free nor unfree. Instead, these spatial organizations were inseparable from their feudal context. Bakhrushin attacked Voronin’s progressive teleology of free sloboda, feudalization, and finally village (to be overcome by the tsar’s liberation of the serfs, then bourgeoisification, and finally communism) as politically sinister.16 For Bakhrushin, this teleology retroactively designated pre-feudal autonomous configurations as backwards, implicitly deeming enclosure and feudal capture as the forward march of progress. This belied the reality of different feudal settlements as multifaceted yet contemporaneous, whose combined subsumption and transition to capitalism were uniquely contingent and oppressive.

Indeed, this history proves crucial for understanding social reproduction and the demands of gendered labor as part and parcel of capital’s reproduction. As the Italian feminist thinker Leopldina Fortunati explains:

while as a slave or serf, i.e. as the property of the master or the feudal lord, the individual had a certain value. But as a “free” worker under capitalism, the individual has no value: only his or her labor power has value. Thus the other side of the transition from pre-capitalist to capitalist “freedom” is a total stripping of value.17

This de-valorization, for Fortunati, makes possible the phenomenon of domestic labor qua un-waged reproduction. Indeed, notions of the transhistorical family and village undergirding an essential de-valorization of gendered work can be seen in the political programs of Voronin’s contemporaries. In an influential pamphlet, fellow Soviet official and intellectual Alexandra Kollantai wrote that “it is necessary for the collective to assume all the cares of motherhood that have weighed so heavily on women, thus recognizing that the task of bringing up children ceases to be a function of the private family and becomes a social function of the state.”18

Countering these critiques, Voronin sought to identify contingencies within peasant spatial organization, reinscribing or embedding within its architectural aesthetics a contested process of knowledge formation—one whose beauty deserved to be enjoyed by the new ruling class of workers. According to Rebuilding, peasant spatial aesthetics arise as a product of struggle through time: distinct historical struggles between peasants and their overlords accrue knowledge from below (in the form of peasant political alternatives) that is then reflected in architecture. Thus, the repair or rebuilding of these older forms is part of building a future defined by new social relations of production and reproduction, reflecting kernels of past alternatives. In describing the architect’s place amid this historical mediation, Voronin wrote that “he should not subordinate his work to the task of ‘historic reconstruction’ but rather to that of planning a new socialist town to meet the needs that will arise during many coming years of economic and cultural development.”19 In essence, architects had to meet the bare needs of life amid the rubble and the transcendent aesthetics needs of the utopian life to come. They had to navigate concrete problems of immediate use, efficiency, and durability while at the same time envisioning a future mode of living by a subject not yet in existence—all while maintaining the historical specificity of peasant life and Russian design as a product of working-class labor and history.

These complex problematics of fixity and futurity in the midst of dire need compose Voronin’s theory of renewal. In Rebuilding, Voronin aptly identifies renewal as an epistemological crisis for the practice of architecture. Building socialism in the wake of systematic destruction would necessitate the elevation of architects from capitalist technocrats and aestheticians to productive organizers and planners. The scale of destruction opened up an arena wherein socialist architects could respond to these revolutionary needs within a central plan, implementing worker building practices and aesthetics top-down via a comprehensive urban plan.

At the same time, Voronin reasoned that the totalizing plan was problematic. Specifically, he recognized that previous modernizing initiatives were prone to dismantling historical remnants in the name of efficiency. This is something that Voronin in other works attributes to the misplaced fervor of the early Soviet Union, but which in Rebuilding he links to a global impulse towards an international modernism that was firmly embraced by fascism. Indeed, following the war, Voronin saw modernist aesthetics as inseparable from the enemy’s attempt to “uproot the national self-consciousness of our people and to prevent any possible restoration of our culture.”20 As such, Voronin imagined a conscious and rational inclusion of “Russian” cultural signifiers as a way to mediate between the central plan and the existing reality of the Russian landscape as a unique product of history and culture.

Speaking of the rural abode, Voronin argued for the inclusion of “every positive feature that the people have worked out in the course of centuries combined with the best examples of modern … houses, always of course, taking into consideration the specific features of life in the particular collective farm or region.”21 More than a collage of new and old, Voronin saw this solution as a process of mediation between the architect and the masses, a dialectic between elite and peasant knowledge. By taking the composite knowledge of peasant history and distilling it into design signifiers (under a nationalist umbrella), the Soviet architect, in Voronin’s vision, could integrate those components with an abstract knowledge of Marxian political economy and rationally deploy dialectical syntheses in the new environment. However, the political horizon of this process was at the mercy of the intellectual/bureaucrat, upon whom the task of interpretation and implementation ultimately fell. Voronin rejected the rote reduplication of “stereotyped classical forms” (as an aestheticization of this organic knowledge), arguing instead for the building of cultural forms that reflect a specific locale’s future orientation, or the needs that would arise in relation to a specific and contingent context following a national, abstract goal.22 This renewal, a historically-inflected future arrangement in the minds of revolutionaries here and now, was emancipatory, yet fraught with the ideology of the present. These ideas of authenticity proved susceptible to aesthetic notions of provenance and political notions of revolutionary fidelity, which, as we will see, contrast with Lin’s feminist approach grounded in an implicit critique of the social reproduction of capital.

Voronin explains that “we do not mean to say that the architect should return to the ‘pre-project’ and ‘pre-draft’ system of the masters of ancient Kyven-Rus, but we still do not want him to be an armchair ‘writer,’ but instead to live by direct impressions of the living ancient city, which he must recreate.”23 The paradox of a “living ancient city” demonstrates the contradictory implications within the project of renewal. On the one hand, Voronin hoped to utilize the best elements of premodern design as the synthetic results of peasant consciousness and working-class resistance. Voronin wanted the trained architect-intellectual to wrest classical aesthetics away from feudalism and place it back among the peasantry (that is, the new socialist masses). On the other hand, the reduction of this history to a series of aesthetic conditions speaks to a process of extracting knowledge from peasants and placing it in the hands of architects who could interpret historical signifiers within a scientific, and thus seemingly universalized, approach to design.24 Perhaps more problematic is the way this approach falls back on a notion of aesthetics as merely a philosophy of beauty, an evaluation of design elements based on their aura. Indeed, Voronin argued that to create old styles through contemporary design practices would only introduce “counterfeits” that detract from the “genuine monuments of the past.”25

In Rebuilding, it is hard to judge whether this authenticity is indeed a return to the aura of capitalist art or something more material, such as an appropriateness of a given intervention vis-à-vis social conditions. Authenticity in the political project of renewal is an unstable concept, and this ambiguity proved ill-equipped to account for the patriarchal authority endogenous to both intellectual attitudes and peasant habitation alike. In Lin and Liang’s remediation, and especially in Lin’s other architectural critiques, we see a concrete attempt to examine these competing tensions in revolutionary knowledge production. Ultimately, in the translation of Rebuilding’s political analytic into the Chinese context, the instability of Voronin’s conceptual intervention opened up a radical potentiality: by bypassing the architect as the interpreter of renewal, Lin and Liang instead fixed identity as its target, thus redefining revolutionary design as the renewal of landscape qua the domain of reproduction and the architect itself.

Reading Renewal in the Chinese Context

Chinese revolutionaries displayed a keen awareness of the role of culture in mediating revolutionary subject formation. Indeed, in one important text sometimes credited with initiating the Cultural Revolution, future Gang of Four member Yao Wenyuan took to task the romantic view of the abolition of serfdom by Hui Rui, a Ming dynasty official. In the essay, Yao echoes much of Bakhrushin’s critique of Voronin, arguing that the supposed liberation of serfs by an enlightened aristocrat amounted to a mechanism of feudal consolidation (gonggu, 巩固) by a waning class (the landed gentry). Most importantly, Yao argues that the supposedly emancipatory moments of feudal formation were vulnerable to reactionary articulations when interpreted by the managerial class of the PRC. These concerns haunted Lin Huiyin and Liang Sicheng’s political environment, with critiques of “classical restoration” (fugu 复古) taking center stage in the early years of PRC architecture scholarship.26 Integrating these concerns, Lin and Liang’s version of Voronin’s thought, while not dispensing with classical design, identifies national architecture as a project of future world-making and intellectual renewal, not of historical interpretation. They steer national aesthetics away from ornament and towards the patterns and environments of domestic and social reproduction.

In 1952, Lin and Liang published their translation of Voronin’s Rebuilding (based on the English-language London text) through the Longmen Joint Publishing House, a Shanghai-based importer of foreign science and technology resources.27 The translation came fresh off the heels of a systematic investigation by Lin into global state-funded or state-facilitated dwelling projects in the wake of the Great Depression. Within these surveys, she sought to unravel the potentials and limits of top-down, wide-scale construction projects, from nineteenth-century railroad section houses to the prefabricated experiments of the US Works Project Administration (WPA).28 Lin saw programs like the WPA as a potential shift in global architectural thought while remaining critical of their underlying impulses and historical precedents. She argued that “residential design [in the first half of the twentieth century], with few exceptions, has always been the domain of the propertied class, whether for their own use or for business.”29 Thus, the appearance of working class domiciles was always a product of social relations, which, under capitalism, manifested economic terms between land’s value and laborers’ surplus value.

While these texts take for granted private land ownership, they nevertheless recognize government-provided housing for all workers as necessary to the wellbeing of the nation.30 The authors therefore sought to uncover what elements of Western design practices might be salvageable under new conditions of production. Writing in the immediate aftermath of World War II, Lin steered this generative reading away from fascist mass housing programs that hinged on the exclusion of certain elements and justified broad construction vis-à-vis competition with other nations.31 Lin’s account was instead oriented around the idea of building for possible “understanding and peace between nations.”32 Moreover, these texts identified the domicile as the site of social reproduction, or that which produces the “economic capabilities of the people.”33 Lin thus considered rational organization of residential spaces to be the key task of Chinese design, both in order to maximize economic capacity and to extend a degree of justice to the worker. This justice entailed improving the conditions of reproduction and allowing workers to enjoy the fruits of accreted national aesthetics in their reproductive spaces (similar to Voronin’s idea of traditional architecture as a signpost for the history of worker design and struggle).34 These surveys were a kind of translation: from the West to China, and from the private to the public. Moreover, with the fall of the liminal Kuomintang–Chinese Communist Party alliance and the foundation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, we see another translation: from world peace to world communism, and, with it, a self-transformation of the author, from an architect concerned with the technocratic organization of a “peaceful century” to one imagining a mass-driven socialist renewal.35

Rebuilding itself is straightforward; Lin and Liang clearly saw its political expediency and worked to translate it quickly. The real translation, however, occurs in the forward, labeled by Lin and Liang as “notes on the translators’ experience.”36 In it, they sketch out an idea of translation as more than a linguistic phenomenon. They write:

Within the mutual experience of wide-scale destruction of cities and villages, and specifically in relation to the scope of construction processes currently underway, the problems we face are not exactly alike. However, in regard to its spiritual foundation and its root cause, each chapter, and each line of [Rebuilding] warrants our study.37

Here, Lin and Liang make a claim for the translatability of the text. Despite different contexts, something internal to Rebuilding’s production warranted reception not only in another language but in another political-historical space. The translatability of Voronin’s text, according to Lin and Liang, lay not in its depiction of a similar situation, but in its insistence that construction work be brought under the rational organization of a central plan mediated by both those who build and those who inhabit the outcomes. This dialectical engagement, for Lin and Liang, would dissolve the distinction between worker and architect (as a kind of intellectual) while inter-determining social relations through physical construction. This is a dissolution, not a sublation. As such, Lin and Liang’s key intervention was to define socialist culture as a future potentiality encompassing both tectonic design and the social organization of reproduction, in contrast to Voronin’s vision of culture as a historical residue (that stands in for the living peasant class) and a post-hoc aesthetic ornamentation to accommodate it.

Lin and Liang began their forward with a critique of the reconstruction already underway. Whereas Voronin critiqued his own country’s initial efforts for their bricolage of hypermodern and faux-traditional aesthetics, Lin and Liang’s critique was not stylistic in nature. For them, the transfer of rebuilding decisions from the field of architecture to socialist/state agencies starting in 1949 blinded reconstruction efforts to fundamental contradictions, thereby essentially duplicating capitalism’s own systemic blindness and threatening the socialist project with the decentralized hodge-podge characteristic of Western skylines (which facilitated capital’s underlying forms of labor and reproduction).38 Instead, Lin and Liang saw the opportunity for reconstruction to probe the very possibilities of social organization. Indeed, speaking of a report on construction errors overseen by the People’s Daily, which focused on questions of safety, labor expenditure, materials, and economics, Lin and Liang called for a deeper critique (jiantao, 检讨): “the scope of these criticisms can still be broadened; we still should search for the more fundamental questions.”39

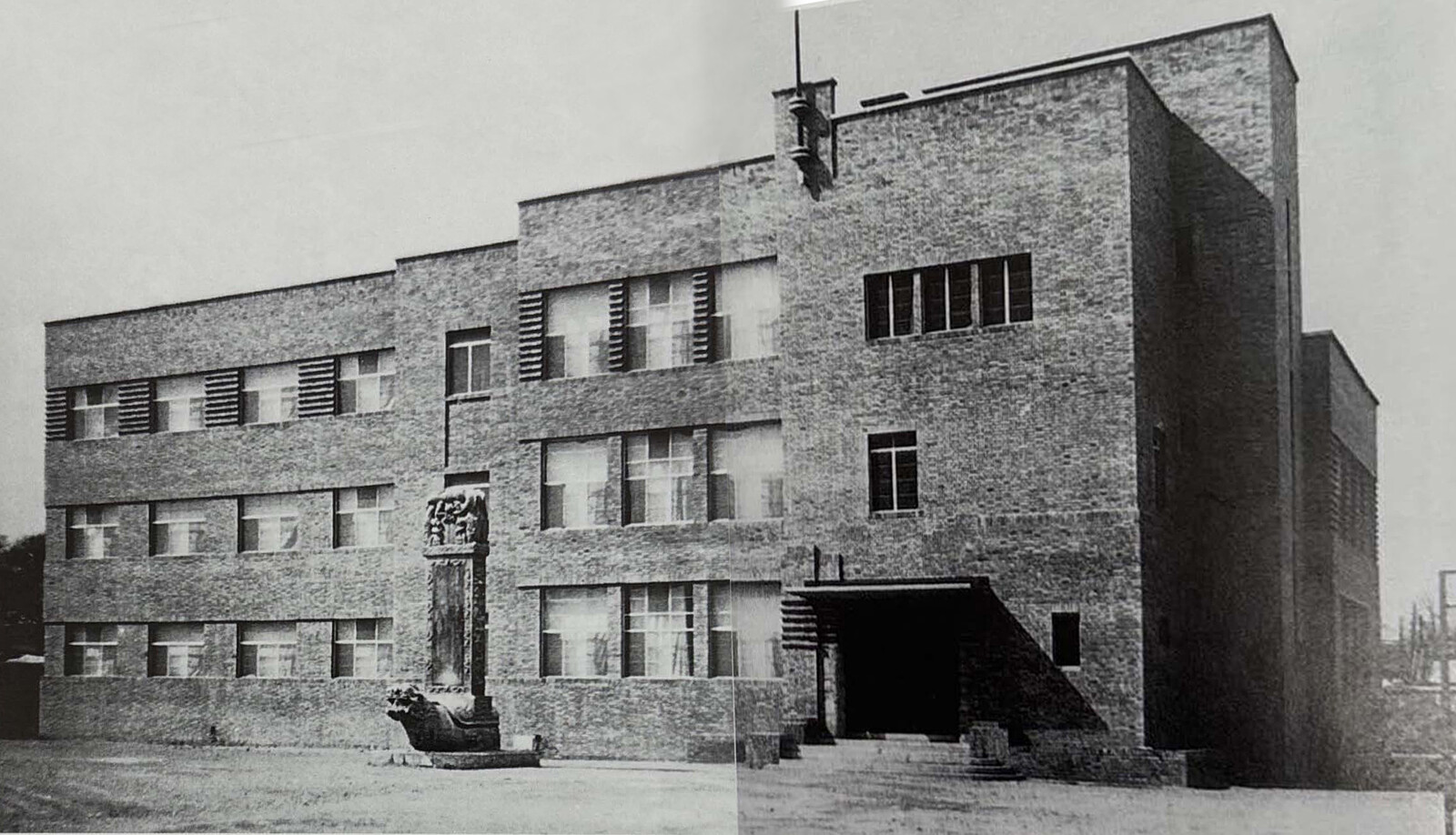

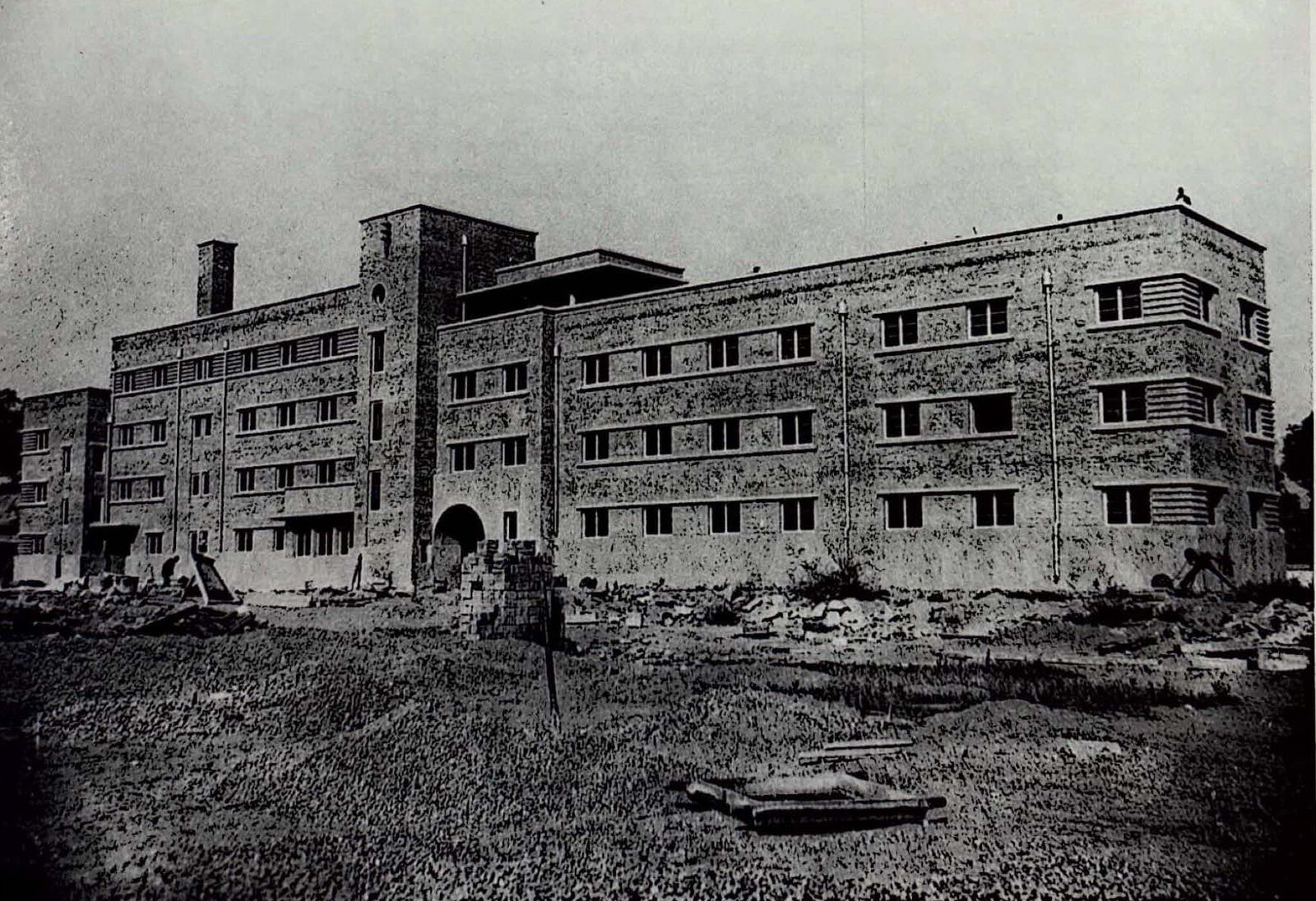

Beijing University Women’s Dormitory, designed by Lin and Liang in 1932. Photographed in 1934. Source: Liang Sicheng 梁思成. Liang Sicheng Chuanji, di Jiu Juan 梁思成全集,第九卷 [The Collected Works of Liang Sicheng, Volume 9]. Beijing 北京: Zhongguo Jianzhu Gongye Chuban She 中国建筑工业出版社 [Chinese Architecture and Building Press], 2001, 16-20.

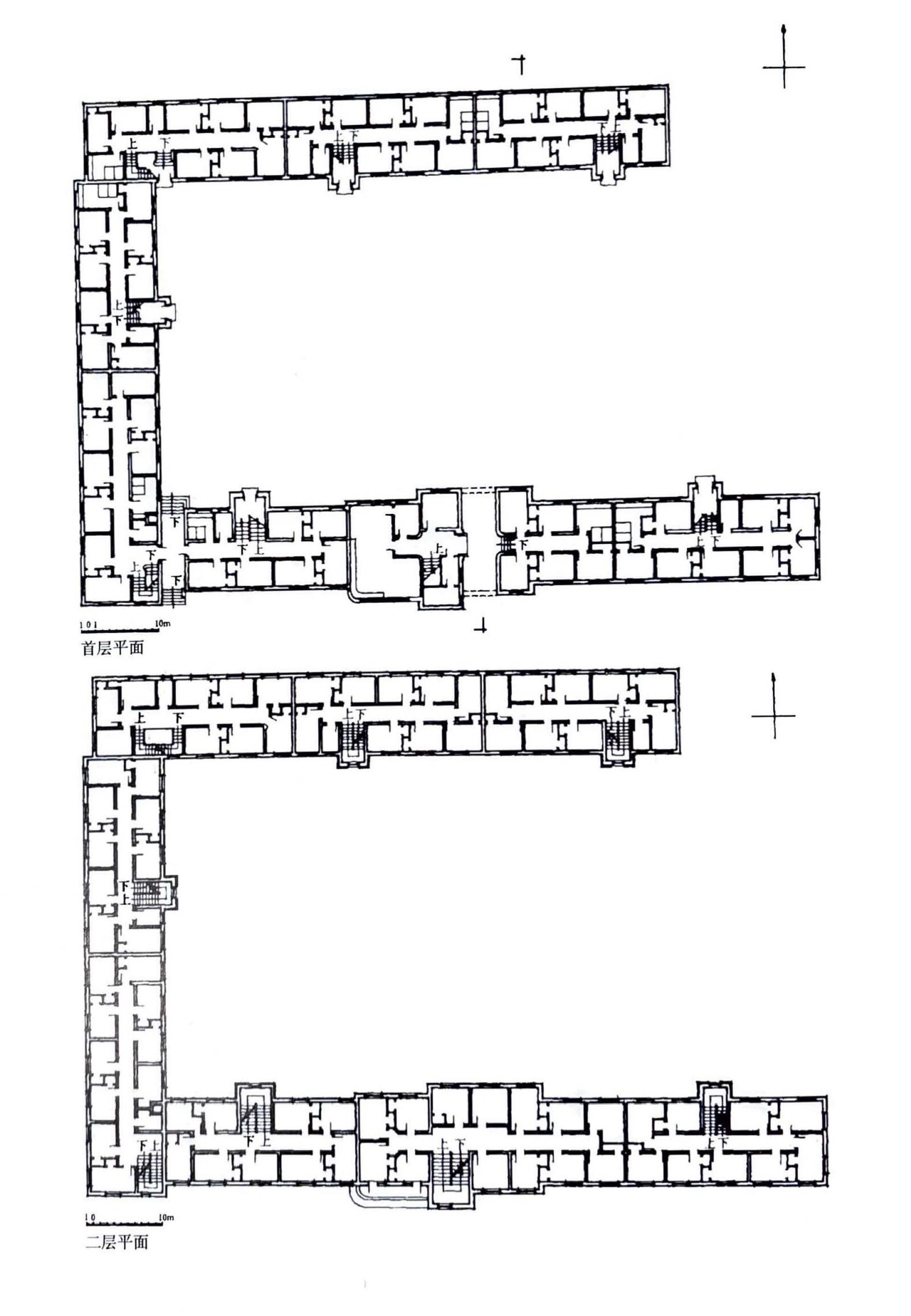

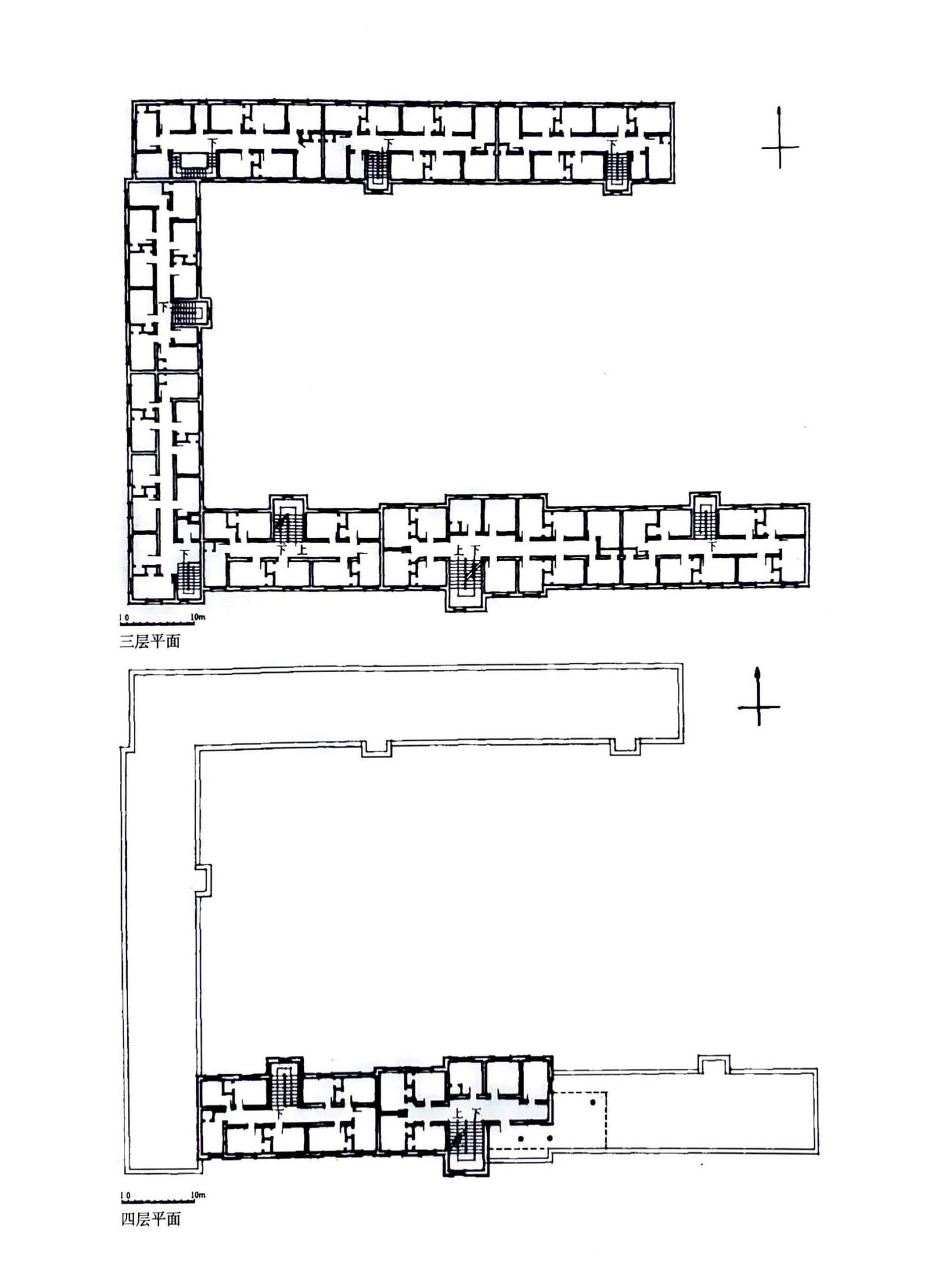

Floor plan of Dormitory. Source: Ibid, 18.

Floor plan of Dormitory. Source: Ibid, 19.

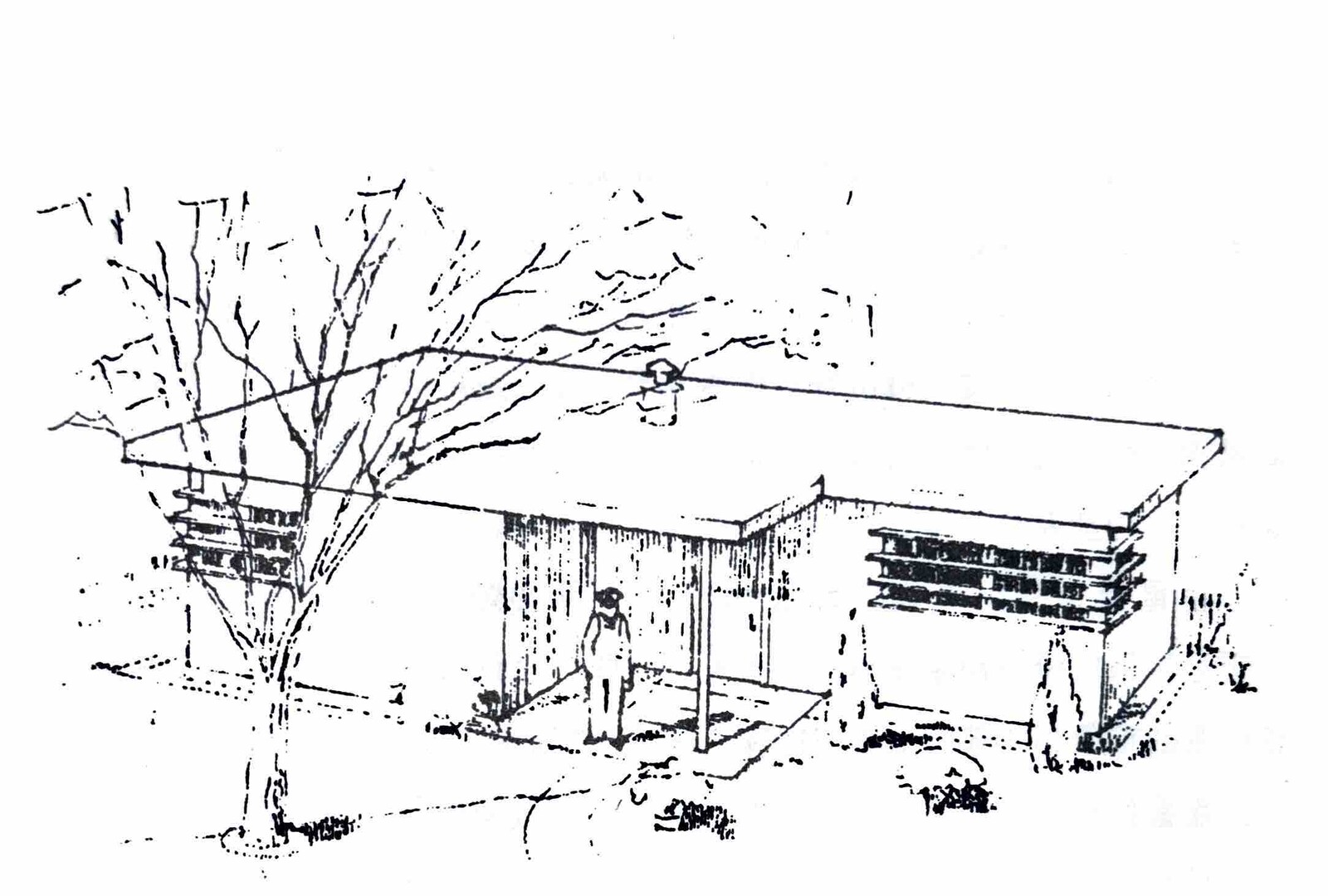

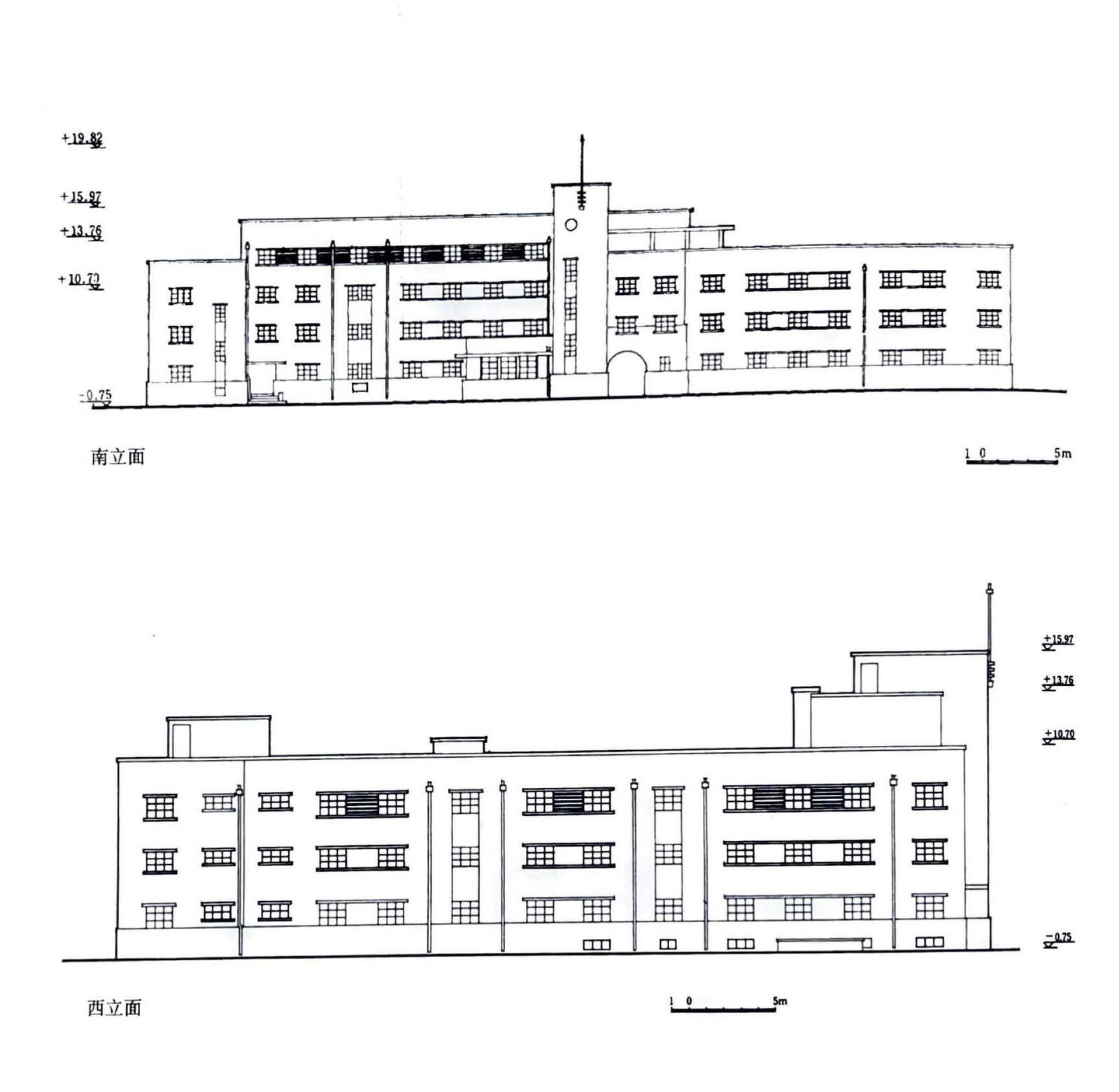

Elevation drawing of Dormitory. Source: Ibid, 20.

Beijing University Women’s Dormitory, designed by Lin and Liang in 1932. Photographed in 1934. Source: Liang Sicheng 梁思成. Liang Sicheng Chuanji, di Jiu Juan 梁思成全集,第九卷 [The Collected Works of Liang Sicheng, Volume 9]. Beijing 北京: Zhongguo Jianzhu Gongye Chuban She 中国建筑工业出版社 [Chinese Architecture and Building Press], 2001, 16-20.

The central question for the two architects was how to think of design as a synthetic, horizontal process of total mobilization. If the Communist Party had rationalized control of the state under a single apparatus in order to implement socialism (the so-called dictatorship of the proletariat), then the determination of the physical environment should be subjected to the same rationalization (in this case, the plan).40 Here, they differed strongly from Voronin. Whereas the Soviet architect saw the plan as a complicated necessity, Lin and Liang saw it as politically liberatory. Their forward argues that the construction of the built environment was dialectically co-constitutive (xingying xiangsui, 形影相随) of not only new economic relations but also wider relations that supersede capitalist categorical divisions (e.g. the strictly economic). As such, the built environment should be the focus of the same kind of intention and thought that characterized economic planning.41 This holistic view of mass political mobilization as a kind of total plan represents the condition of possibility for a left-feminist critique of early Maoist developmentalism. For Lin and Liang, economic planning was one side of the overall social plan: production. On the other side, which they argued should fall within the domain of socialist architecture, lay social reproduction.

In describing the rational construction of housing following the war, Lin and Liang argued for a plan that would be “three dimensional … [which] does not just concern economy, production, and residence, but also culture, entertainment.” 42 For the pair, housing was more than just its “blueprints and construction instructions.”43 The social relations behind the construction of the house should be the target of socialist politics and socialist architecture, as should the political relations inside the house. This desire to bring social reproduction under the auspices of the rationally controlled plan implicitly strikes at a fundamental problem and oversight of Voronin’s approach and of Marxism more broadly: namely, the positioning of reproduction and domestic labor as outside the sphere of value production, which leads to shaky conceptions of the domicile as either a “precapitalist vestige” or a “non-capitalist island” (a separate mode of production embedded within capital).44 This instability, and the way it degrades gendered, reproductive work, reveals the limits of Rebuilding’s vision. While Voronin may have tempered his nostalgia for past configurations of reproduction, his idea of socialist life never reached beyond the contours of aesthetic experience. In pushing for a total project of social engineering, however, Lin and Liang attempt to break through an epistemological limit in Soviet renewal. In Fortunati’s words:

Marxian analysis describes only one half of the process of production—the production of commodities—and cannot be extended per se to cover reproduction; and furthermore, an analysis of the entire cycle of production cannot be made until reproduction has been analyzed too. This latter analysis can only be made if Marxian categories are not used dogmatically and if they are combined with feminist critique.45

We can see this feminist critique in Lin’s contemporaneous polemics against male architects all too willing to reinscribe habitation and reproduction as an historical-aesthetic question. Indeed, Lin’s arguments allow us to see how this aestheticization was precisely the logic of capital, which posited the domain of reproduction outside itself in order to produce value without paying a wage. This critique, like her divergence from Voronin, centers on her view of history as the grounds wherein reproduction is obscured and current gender hierarchy legitimized. Lin viewed history through the present, specifically a present overdetermined by the reality of colonization. She argued that both the aesthetics of an ossified culture and the dreams of pure functionalism were equally the result of empire’s epistemological dominance. Speaking of her contemporary, architect Dai Nianci, Lin quipped:

Reading only his words, the reader would be convinced that [Dai] had grasped the essence of the Chinese national form, but his architectural drawings reveal the particularity of Western forms … his creation is indeed likely only to produce a second generation of semi-colonialism through the unconscious imitation of the appearance of modern buildings in Western magazines.46

What is striking about this critique is its object. Dai’s designs stood precisely in opposition to the functionalism of practical construction and the high modernism of early Communist foreign-facing architectural landmarks. Dai was known for his work on domestic-facing cultural institutions, such as the National Gallery of Art in Beijing, with which the state was directly involved. He saw these buildings as opportunities to re-create the splendor of proto-proletarian labor through aesthetic signifiers embedded in a progressive history.47 Yet, Lin saw how the effort to boil culture down to its representative features was intrinsic to the ideology of capital, which, even in explicit attempts to build outside it, manifested itself subconsciously. Thus, for Lin, the past could not be mined for aesthetic authenticity in order to repackage it as an architectural typology for a socialist nation. Communism could only be imagined as a future condition, and that meant that its contents (gender equality, class abolition, technological abundance, etc.) had to be theorized beyond the current conceptual apparatuses. In other words, the domains and spheres of what would be brought under conditions of equality had to be broadened, as did the construction that would be responsible for materializing and reproducing that equality. Lin and Liang brought the obfuscated logics of capital, empire, and patriarchy into the magnifying prism of architecture. This was not only a shift in the very definition of design, but also a necessary condition for a new socialist architecture and (the continued reproduction of) a feminist epistemology of the Chinese revolution.

(Re)producing a New Architect

For Lin and Liang, this constant expansion of the categorical objects of revolutionary renewal was also a process of rearticulating the place of the intellectual, themselves included. Indeed, they credited their initial reading of Voronin’s text with the realization that their past training was part and parcel of the Republican landscape:

Today’s Chinese architects, without exception (translators included), directly or indirectly learned abroad. The older ones studied ancient Greece, Rome, and the Renaissance, while the younger ones studied the crystallization of capitalist art theory: that is, the so-called “functionalism” (mechanical materialism) of “modernization” or the genre of “international style” (cosmopolitanism). We have been drunk for decades on these two toxins. We have become the accomplices to the imperialist capitalist cultural invaders.48

Unlike Voronin, who was educated in Russia, Lin and Liang studied architecture in the United States. Barred from the architecture department at the University of Pennsylvania on account of her gender, Lin realized that her spatial consciousness was likewise shaped by the imperial project. Therefore, renewal had to be a dialectic not just between the plan and the site, but also between the architect and the (global) masses. It had to be feminist but also internationalist. Rebuilding was as much a response to the devastation of the Nazis as it was a refutation of Stalinist design, which had long since embraced an aestheticized classicism as dogma, and moreover had ruthlessly consolidated the state and its totalizing modernization objectives. The destruction of ancient architecture to make way for stylized classicism (“counterfeits” in Voronin’s words) and academic purges no doubt contributed to Voronin’s notion of “authenticity” and the role of the aesthetician in safeguarding it.49 But these ideas were destabilized in their translation by subaltern and gendered subjects. At the open-ended beginning of the Chinese revolution, China had only seven years prior thrown off the shackles of Japanese colonization (and European before that). For Lin and Liang, aesthetics simply could not be thought of as the domain of the elite, because the elite aesthetician was by and large a comprador class. With this realization, Lin and Liang were also able to undermine a conception of aesthetics qua ornamental beauty: “economic construction and cultural construction go hand in hand and cannot be separated.”50 This economic-cultural nexus, for Lin and Liang, existed at the city-scale, not at the level of detail:

When designing, [Soviet] architects not only pay attention to the artistic aspects of individual buildings, but they also deeply understand that each building and its neighbors, whether in terms of convenience of use or aesthetic effect, articulate each other and thus cannot be isolated from one another. Therefore, the advanced architects of the Soviet Union take the city as a whole and design it as a whole with a three-dimensional composition (liti goutu de zhengti sheji, 立体构图的整体设计).51

Thus, through the rational plan, the disparate identities of a new socialist project (worker, farmer, inhabitant, architect, engineer, bureaucrat) could dialogically articulate their cleavages to overcome them—and dialectically construe the environment of their future renewal and reproduction as subject and master of a new political system. Rendered through the experience of the Chinese Revolution, Voronin’s Rebuilding became the instrument for Lin and Liang to critique and rearticulate their role as Western-trained architects, and with it the siloed horizon of “culture” that training upheld.

Born in 1901 to a prominent Qing-era reformer, Liang Sicheng is commonly referred to as “The Father of Chinese Architecture,” having founded some of the country’s first architecture departments, including that of Tsinghua University. He worked in the field of architecture and archeology throughout the Republican, Occupation, and Communist periods, contributing to significant works both in China and abroad, such as the Monument to the People’s Heroes and the United Nations Headquarters in New York, as well as writing the first works on the history of Chinese architecture, translating the historical building practices of dynastic China into the language of modern design. Lin Huiyin (b. 1904) was a Chinese poet, novelist, and architect. She was the author of several important works of pre-war fiction, such as Ninety-nine Degrees (1931). Having been denied a degree in architecture at the University of Pennsylvania on account of her gender, Lin went on to attain degrees in Fine Arts and Stage Design. Upon her return to China following the end of World War II, Lin joined the architecture department of Tsinghua University, authoring important texts on traditional and modern Chinese design and supervising graduate projects. She, alongside her husband Liang, contributed to the design for the national emblem, the Beijing Capital Plan, and co-designed the Monument to the People’s Heroes.

Nikolai Nikolaevich Voronin, “О Восстановлении Древнерусских Городов {On the Restoration of Ancient Russian Cities},” Исторический Журнал {Historical Journal} 3 (1945): 56.

Lin and Liang chose to emphasize this line and include it in their translator’s forward: Lin Huiyin 林徽因 and Liang Sicheng 梁思成, “苏联卫国战争被毁地区之重建》译者的体会 {Translators’ Experience of ‘Reconstruction of the Regions Destroyed in the Soviet Patriotic War’}” in 林徽因集:建筑 · 美术 (下){Lin Huiyin Collection: Architecture and Art} (Beijing: 人民文学出版社 {People’s Literature Publishing House} (2014), 356.

N. N. Voronin, Rebuilding the Liberated Areas of the Soviet Union (London: Hutchinson & Co. Ltd., 1945), 13.

Liangyong Wu, Rehabilitating the Old City of Beijing: A Project in the Ju’er Hutong Neighbourhood (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1999), chapter 2; and Jianfei Zhu, Architecture of Modern China: A Historical Critique (London: Routledge, 2013), chapter 4. Here I refer to the rejection of Liang and Chen Zhanxiang’s plan for Beijing (to which Lin was a contributor and advocate), To be fair, this plan was not merely rejected because of Lin’s involvement, but also for its vision of an administrative center at the periphery of the city. Another early Lin project that was similarly rejected on artistic grounds was her design of the Chinese National Emblem, which was deemed too abstract and bourgeois. Perhaps more indicative of Lin’s relegation to cultural thinker over designer is her involvement in the Asia-Pacific Peace Conference in 1951. Whereas Yang Tingbao designed the hotel for the delegates and Liang the meeting space, Lin was merely invited to present on classical Chinese cloisonné. Most importantly, she was not afforded the same responsibilities as Liang, something that colored her entire career and persisted after the revolution. There was also the reality of reproductive work in her own life, wherein, despite worsening tuberculosis, she was tasked with caring for hers and Liang’s children while he pursued architecture at the highest echelons of the Communist Party. See her letters to Wilma Fairbank for her most explicit critiques of gendered reproductive work within her own life, and how it inhibited her political and design work, in Xiao Chen 若萍, “一代才女林徽因 {The Talented Lady of Her Generation},” 读书 {Reading in Chinese}10 (October 1984): 113–21.

Alexander Alexandrovich Formozov “Роль Н.Н. Воронина в защите памятников культуры России {The Role of N.N. Voronin in the Protection of Russian Cultural Monuments} Российская Археология {Russian Archaeology} 2 (2004): 176.

Formozov, “The Role of N.N. Voronin in the Protection of Russian Cultural Monuments,” 174.

Formozov, “The Role of N.N. Voronin in the Protection of Russian Cultural Monuments,” 176.

This will become clearer in my discussion below of the contents of Rebuilding, but Formozov similarly assesses the goals of Voronin’s published works during the late 1940s, see: Formozov, “The Role of N.N. Voronin in the Protection of Russian Cultural Monuments,” 175-76.

“Books and Articles on Russia Published in 1945,” The Russian Review 5, No. 2 (Spring 1946): 119.

Sergey Vladimirovich Bakhrushin “Воронин, Н. Н. К Истории Сельского Поселения Феодальной Руси {N. N. Voronin on the History of Feudal Russian Settlements},” Историк-Марксист {Marxist-Historian} 6, no. 58 (1936): 191–94.

Voronin, Rebuilding, 76, 26.

Voronin, Rebuilding, 21, 48.

Voronin, Rebuilding, 48.

Bakhrushin, “N. N. Voronin on the History of Feudal Russian Settlements,” 193.

Indeed we can see how Voronin’s chronology adopts the most Hegelian tendencies of the young Marx (as rendered through Stalin). I’m speaking here of early Marx’s nebulous formulation of primitive communism in relation to feudalism, but more relevant is Stalin’s relatively mechanistic or “economistic” adoption of this chronology, e.g.: “The slave system would be senseless, stupid and unnatural under modern conditions. But under the conditions of a disintegrating primitive communal system, the slave system is a quite understandable and natural phenomenon, since it represents an advance on the primitive communal system,” Joseph Stalin, “1938: Dialectical and Historical Materialism,” trans. M., Marxists.org, September 1938, ➝.

Leopoldina Fortunati, The Arcane of Reproduction: Housework, Prostitution, Labor and Capital, trans. Jim Fleming (Brooklyn, New York: Autonomedia, 1995), 10.

Alexandra Kollontai, “The Labour of Women in the Evolution of the Economy,” trans. Alix Holt, Marxists.org, 1921, ➝. While Stalinism led to a regression in the social status of women and an abandonment of this early revolutionary goal, it is important to note that in the period of Rebuilding’s writing, due to the German invasion and the sheer scope of Nazi military executions, women made up half the agrarian work force, and a new generation of Soviet feminists, like laborer-journalist L. E. Karaseva, used the moment to deconstruct concepts of gendered labor. While indeed Voronin was more likely responding to the critiques that appeared in academic journals, it is important to note that his early works, which reified traditional structures, were published precisely in the moment of Stalinist purges, and that the devastation of the 1940s yielded contradictory messages. These feminist critiques are important in articulating Lin’s critique, which, while contemporaneous with Voronin’s text, unfolded amid the early, experimental years of the Chinese Revolution, much like Kollantai’s early feminist critiques.

Voronin, Rebuilding, 25.

Voronin, Rebuilding, 70, emphasis is my own.

Voronin, Rebuilding, 50.

Voronin, Rebuilding, 47, 25.

Voronin, “On the Restoration,” 56.

Voronin, “On the Restoration,” 56.

Voronin, Rebuilding, 78.

See Yang Tingbao’s influential piece in the Journal of Architecture (founded by Liang), in which Yang (perhaps the most successful early PRC architect and, at times, Liang’s chief competitor), lays out some implicit critiques of Liang’s historical preservationism through the confusion of the term “fugu” (复古). See Yang Tingbao “解放后在建筑设计中存在几个问题 {A few Problems Persisting in Post-Liberation Architecture},” 建筑学报 {Journal of Architecture} 9 (1956): 51-53; and Liang and Lin’s contribution to the debate, Liang Sicheng, Lin Huiyin, and Mo Zongjiang, “中国建筑发展的历史阶段 {Historical Stages of the Development of Chinese Architecture},” 建筑学报 {Journal of Architecture} 2 (1954): 108-121; and Liang Sicheng, “中国建筑的特徵 {Characteristics of Chinese Architecture},” 建筑学报 {Journal of Architecture} 1 (1954): 36-39.

Lin and Liang, “Translator’s Experience,” 353.

Lin Huiyin,“现代住宅设计的参考 {Modern Residential Design References},” 中国营造学社汇刋 {The Society for Research in Chinese Architecture Bulletin}, no. 2 (October 1945).

Lin, “Modern Residential Design,” 270.

This acceptance of private property, however, is due to the context she is discussing (the US and UK). She does indeed critique the system of private property: “Because the UK is a deeply rooted capitalist country and cannot drastically address this issue from a socialist economic standpoint…” However, she does not take this critique much further, partially to focus on a scientific investigation of her case study and partially perhaps to hedge, or at least take nothing off the table as the political regime in China at the time was very much in flux. Lin, “Modern Residential Design,” 271.

See for instance: Nelson Mota Libero, “From House to Home: Social Control and Emancipation in Portuguese Public Housing, 1926-1976,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 78, no. 2 (June 2019): 208-226.

Lin, “Modern Residential Design,” 271-72.

Lin, “Modern Residential Design,” 272.

Lin, “Modern Residential Design,” 270-72.

Lin, “Modern Residential Design.”

Lin and Liang, “Translators’ Experience.”

Lin and Liang, “Translators’ Experience,” 353.

For the consolidation and nationalization of design decisions at the start of the revolution, see Zhu, Architecture of Modern China, chapter 4. This claim refers to this consolidation as well as what Lin and Liang saw as the politicization of architecture and the intervention of bureaucrats in design decisions (notably in regard to capital planning, see footnote 4), which, on the one hand, held political promise but, on the other hand, tended to ignore the contested history of architecture and its internal debates on politics and style.

Zhu, Architecture of Modern China, 355.

Zhu, Architecture of Modern China, 354-55.

Zhu, Architecture of Modern China, 356. By economic planning, I mean the degree of intentional measures (and successes) demonstrated by early price controls, land-leasing, small-scale collectivization within Mutual Aid Teams, and distribution; see: Nicholas Lardy, “Economic Recovery and the First Five Year Plan,” in The Cambridge History of China, ed. Roderick MacFarquhuar and John Fairbank, vol. 14 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 144–83.

Lin and Liang, “Translators’ Experience,” 354.

Lin and Liang, “Translators’ Experience.”

Fortunati, The Arcane of Reproduction, 8.

Fortunati, The Arcane of Reproduction, 10.

Lin Huiyin, “对戴念慈《历史遗产》等的批注 {Annotations on Dai Nianci’s ‘Historical Heritage,’ Etc.},” in Lin Huiyin Collection, 419.

Peter G. Rowe and Seng Kuan, Architectural Encounters with Essence and Form in Modern China (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 124.

Lin and Liang, “Translators’ Experience,” 357.

Voronin, Rebuilding, 78. Voronin uses the word “genuine,” so authenticity is used here in apostrophes to avoid the awkwardness of “genuine-ness.”

Voronin, Rebuilding, 356.

Voronin, Rebuilding, 355, emphasis mine. “Articulate” is taken with some poetic license to capture the meaning of the Chinese “都是互相影响的,” which literally means “all {of which} are mutually influenced by,” but which in this text is explicitly meant to suggest that each building within a landscape affects and is affected by the others. While not quite a direct application of the Marxian notion of “articulation,” my use here is meant to hint at a dynamic of inter-determination comprising both “superstructural” and “base” elements that is similarly well captured by “articulation” (in the common sense) as meaning both a speech-act and a connection of segmented parts.

Asian Feminist Architectural Possibilities is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and Ruo Jia, supported by Pratt Institute.