Aaron Schuster, How to Research Like a Dog

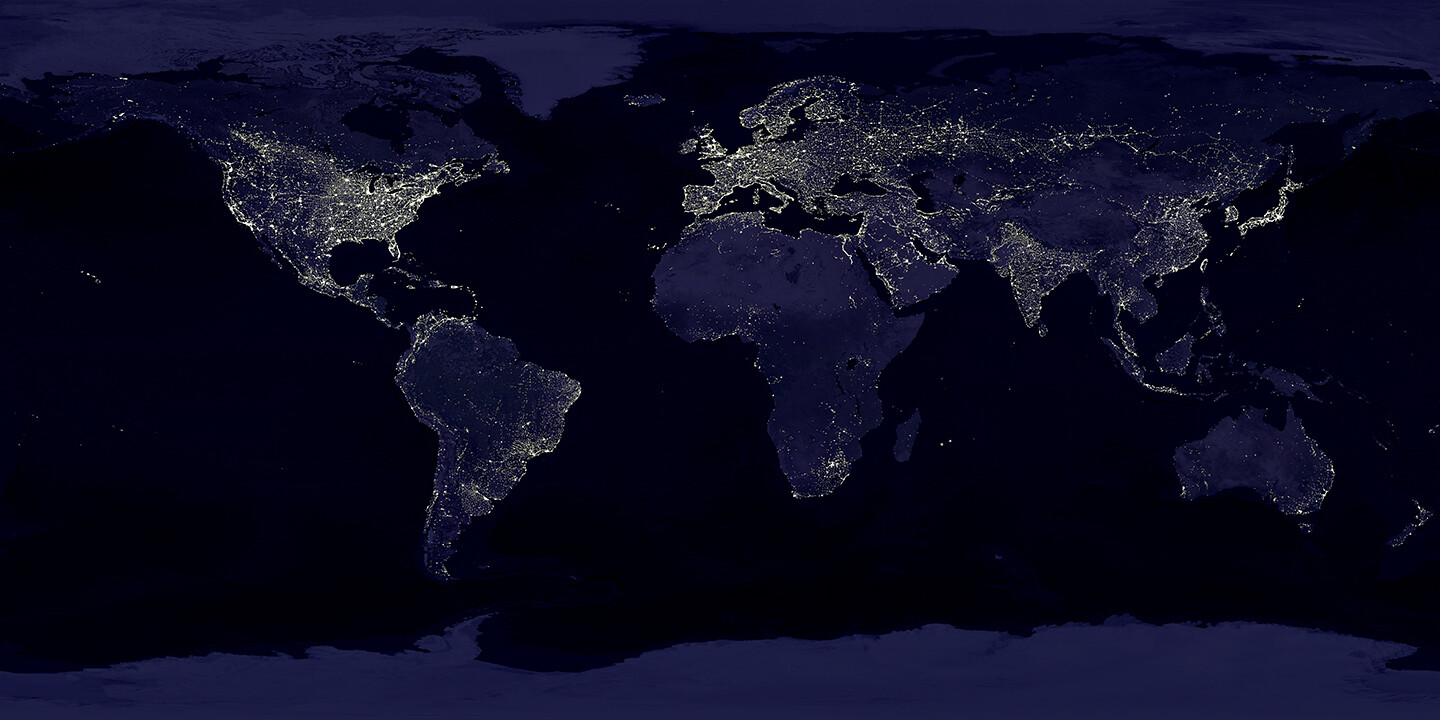

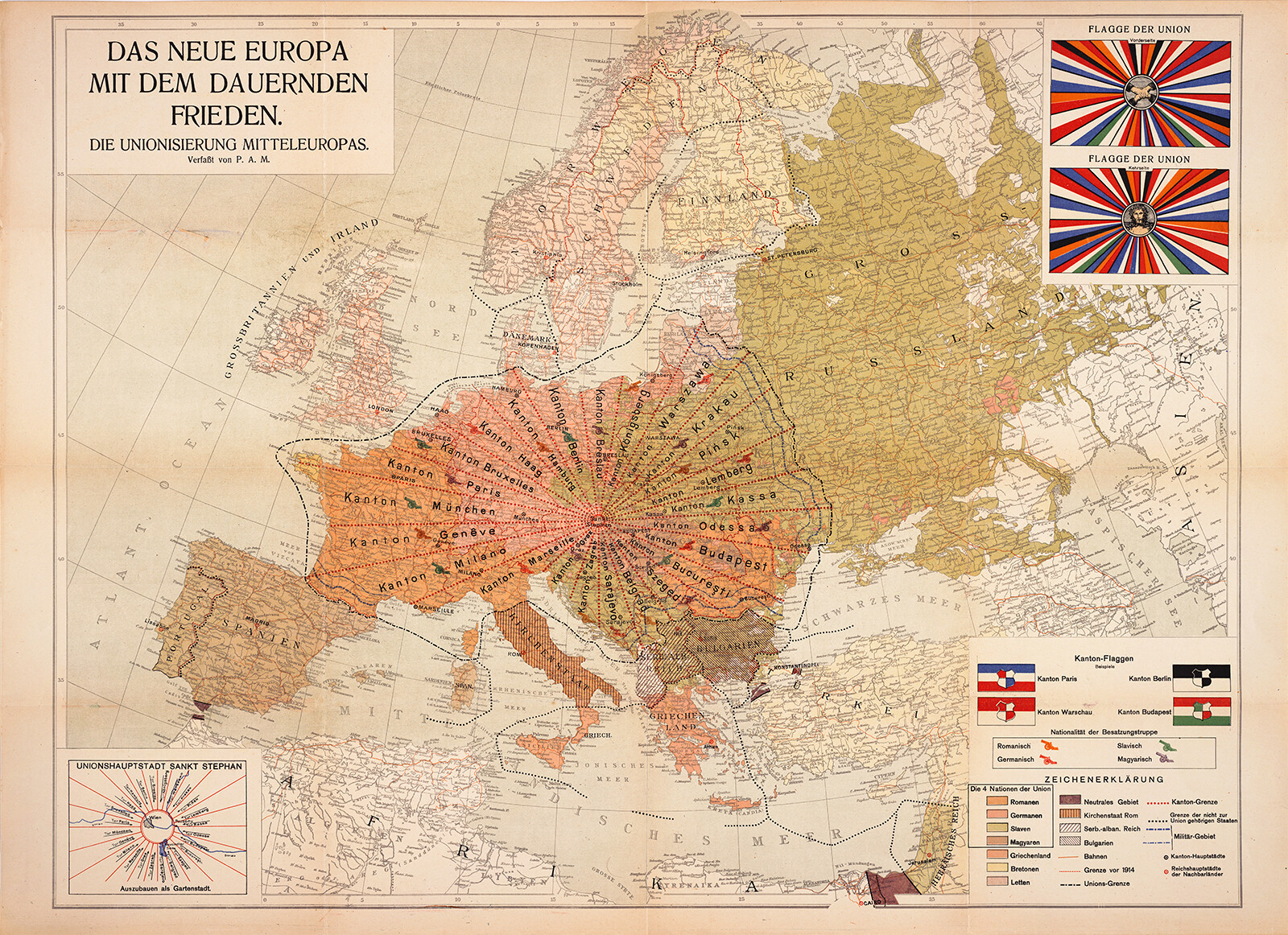

Planetary thinking should be oriented toward the future with a new conceptual framework. The obstacle is that today we still think primarily from the perspective of the nation-state and its economic and military interests. The planetary should not be confused with a new configuration of power between the states, such as a bipolar or multipolar configuration, because this does not change the nature of politics. For this would be the mere continuation of the politics of the nation-state; the difference would only be related to who has more power and more control over resources and the world market.

The neoliberal attack on the humanities in countries such as the UK and the Netherlands makes universities increasingly inhospitable to heterodox forms of life, of intellectual praxis and critical inquiry. Under the circumstances, it is vital that existing institutional forms and habits are supplemented and challenged by forms of self-organization whose autonomy often comes at the cost of extreme precarity.

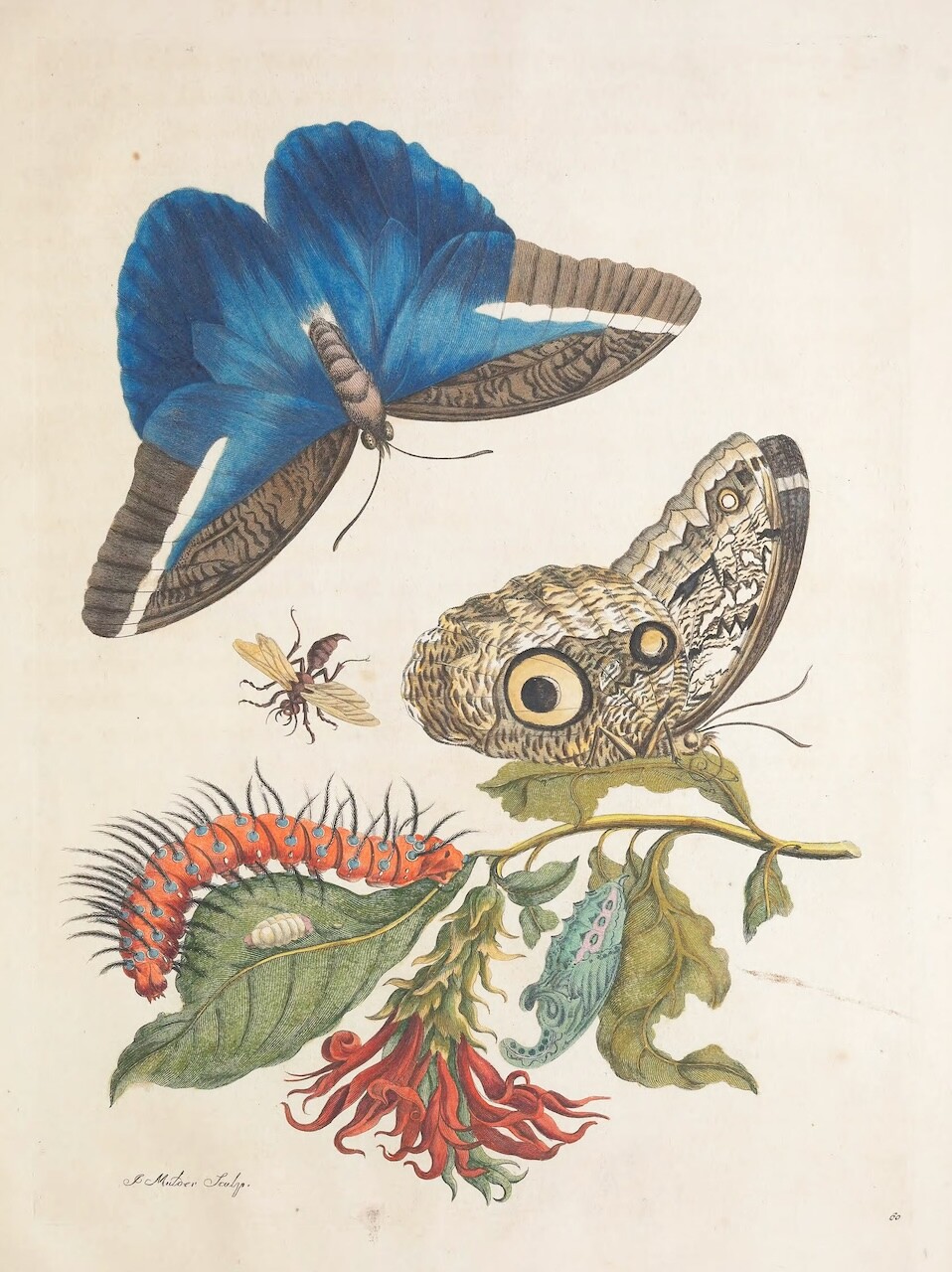

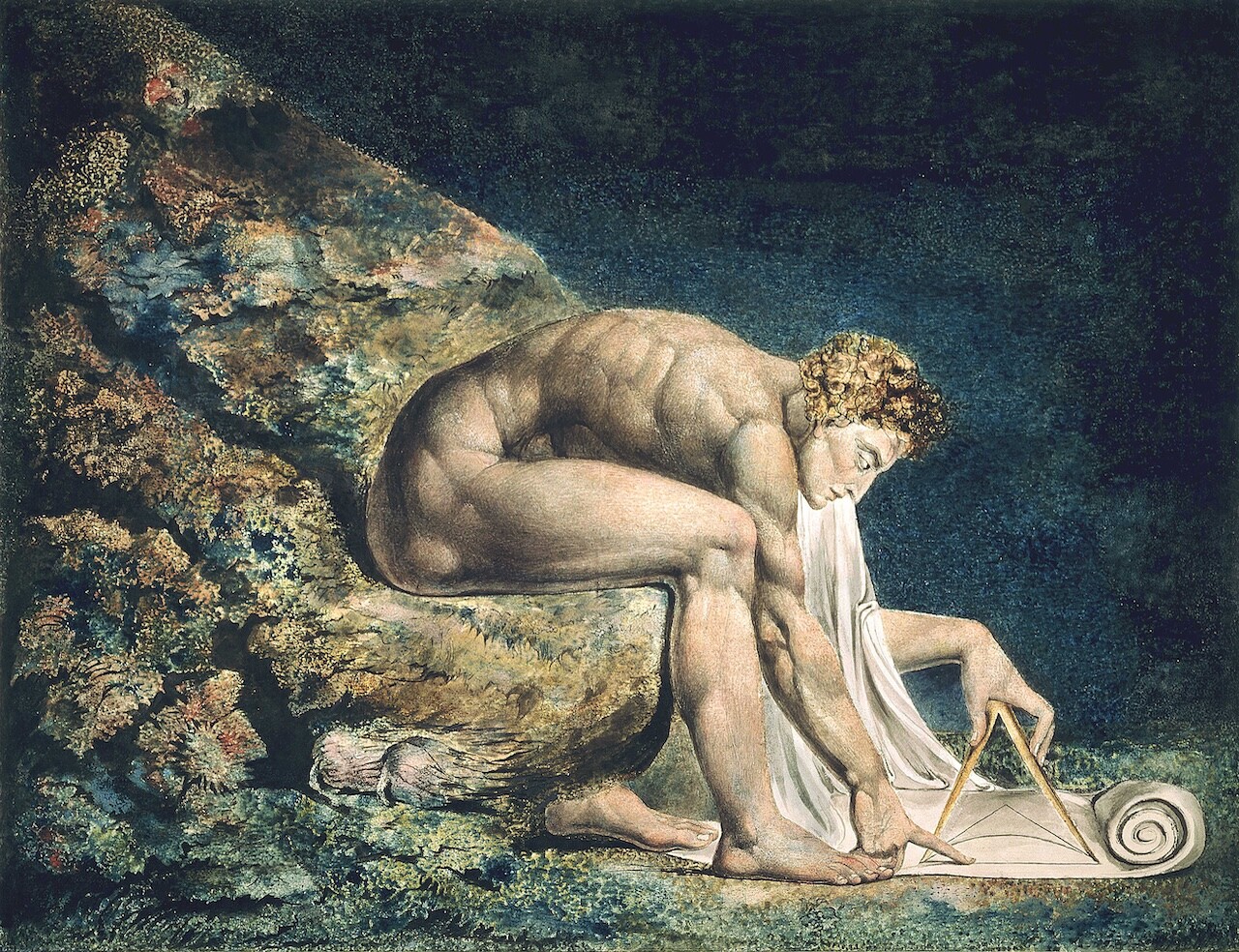

What is, then, organization? Aleksandr Bogdanov’s Essays in Tektology offers two distinct and complementary definitions, one indirect, the other explicit. If human labor discovers that “any product is a system organized from material elements by means of joining them with the elements of energy of human labor,” then it is possible to generalize from this that organization consists of the joining of elements through the expenditure of energy. “No conjunction whatsoever—not only this, biological, but none whatsoever, in the most general tektological sense of the word—can occur without an expenditure of activities,” hence also energy.

Imperial powers will continue competing over resources to maintain the uneven development of the world. Many intellectuals unfortunately share the illusion that these powers will come to the table, listen to each other, work out their differences, and collaborate. But neither culture nor understanding are at stake in this larger power struggle, and those who have not woken up to this will only repeat the “clash of civilizations” cliché by insisting on respect for cultural differences. The East and the West are in fact developing the same plan, the same technology, and the same philosophy of history for domination, and are thus no longer distinguishable in this world process.

One radical strand of modern historical thinking could be termed “potentialism”—a form of historicism that is open to unprecedented actualizations and long latencies, to events transcending their conditions, and to processes of becoming that are not always reducible to classical conceptions of class. Now that it has been recaptured and refunctionalized in the service of algorithmic governance by a planetary elite of AI-pushing space invaders, what potential does the concept of potentiality still hold? How to propagate a potentialism of deviation and divergence, of the improbable-but-necessary, in opposition to the techno-dystopian future that is being made today in Silicon Valley?

Kojève’s journey from philosophy to diplomacy was not a case of accidental wandering but the outgrowth of his Hegelian convictions. He held that critique without action is frivolous, dismissing the “fundamentally nihilist elements, known as ‘intellectuals,’ for whom non-conformity is in itself an absolute value”—those who, like Albert Camus, reveled in moral dissent yet sidestepped the arduous institutional work needed for durable change. A critique, Kojève said, that wants to be taken seriously cannot operate at a distance from the state.

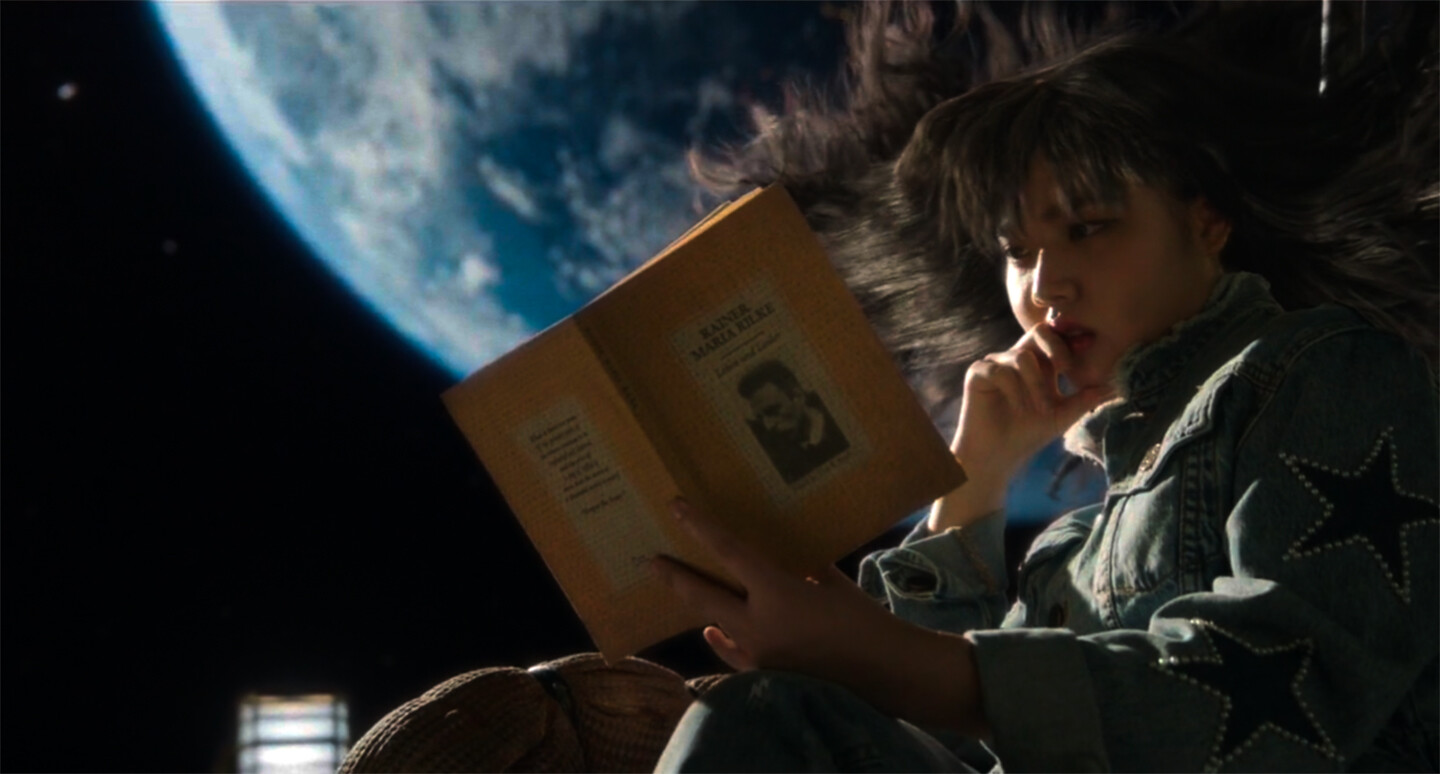

According to Evald Ilyenkov, the dialectic process must have no beginning and no end; it must be infinitely circular. Such an infinite circulation presupposes that at the end of every cosmic period, every humanity takes the decision to explode itself and thus let the universe start a new cosmic period. Here dialectical materialism is inscribed not merely into historical materialism but into the symbolic exchange between universe and humanity, between nature and spirit.

In past centuries, almost every philosopher was addressed according to nationality, and a new school of thought was often prefixed with a nationality. A thinker can only go beyond the nation-state by becoming heimatlos, that is to say, by looking at the world from the standpoint of not being at home. This doesn’t mean that one must refrain from talking or thinking about a particular place or a culture; on the contrary, one must confront it and access it from the perspective of a planetary future.

In the twenty-first century, we can easily sense that this process of destruction and recreation is only accelerating rather than slowing down. The longing for Heimat will only be intensified instead of being diminished; the dilemma of homecoming can only become more pathological. In fact, two opposed movements are taking place at the same time: planetarization and homecoming. Capital and techno-science, with their assumed universality, have a tendency toward escalation and self-propagation, while the specificity of territory and customs have a tendency to resist what is foreign.

It can be difficult to see what is lost when loss is experienced. Freud described melancholia as a condition in which what is lost, beyond any particular object, is ultimately the subject’s relation to the world, which he then describes as a topographical withdrawal back into the self and narcissism, a state he called melancholia. In the process, the relation to the external world is severely compromised. But, Anders asked, could it be possible to start from the opposite premise—that the relationship to the world is never guaranteed a priori?