Given that for those myriad subaltern communities marked as structurally disposable, as incapable of (democratic) rights and the (responsible) exercise of freedom, “the fascism which liberal modernity and civil society have always required has never abided by this order’s mendacious separation of the political from the aesthetic,” how could one expect an art keyed to the operation of these structures, or grounded in the historical praxis of these communities, to conform to the artifice of such notionally separable strictures as those that divide aesthetics from politics, form from content, present from past, living from dead?

Within the shared sociohistorical field of black cultural practice, within the neglected realms of the studium, homogeneity and heterogeneity are instead bound up in shifting but complementary relation. In this model, repetition and differentiation are not antagonistically opposed. Difference is not exclusionary, and similitude is not unprepossessing.

In contemplating Camera Lucida now, in the wake of the fortieth anniversary of its publication, I am moved to ask: How could a book so intensely bound up with photography and loss show so little generosity, and why, today, should we heed its call? Beyond this, what might insights from black studies bring to bear on a book so indebted to the identification and rejection of difference in the expropriative formulation of Barthes’s inner self?

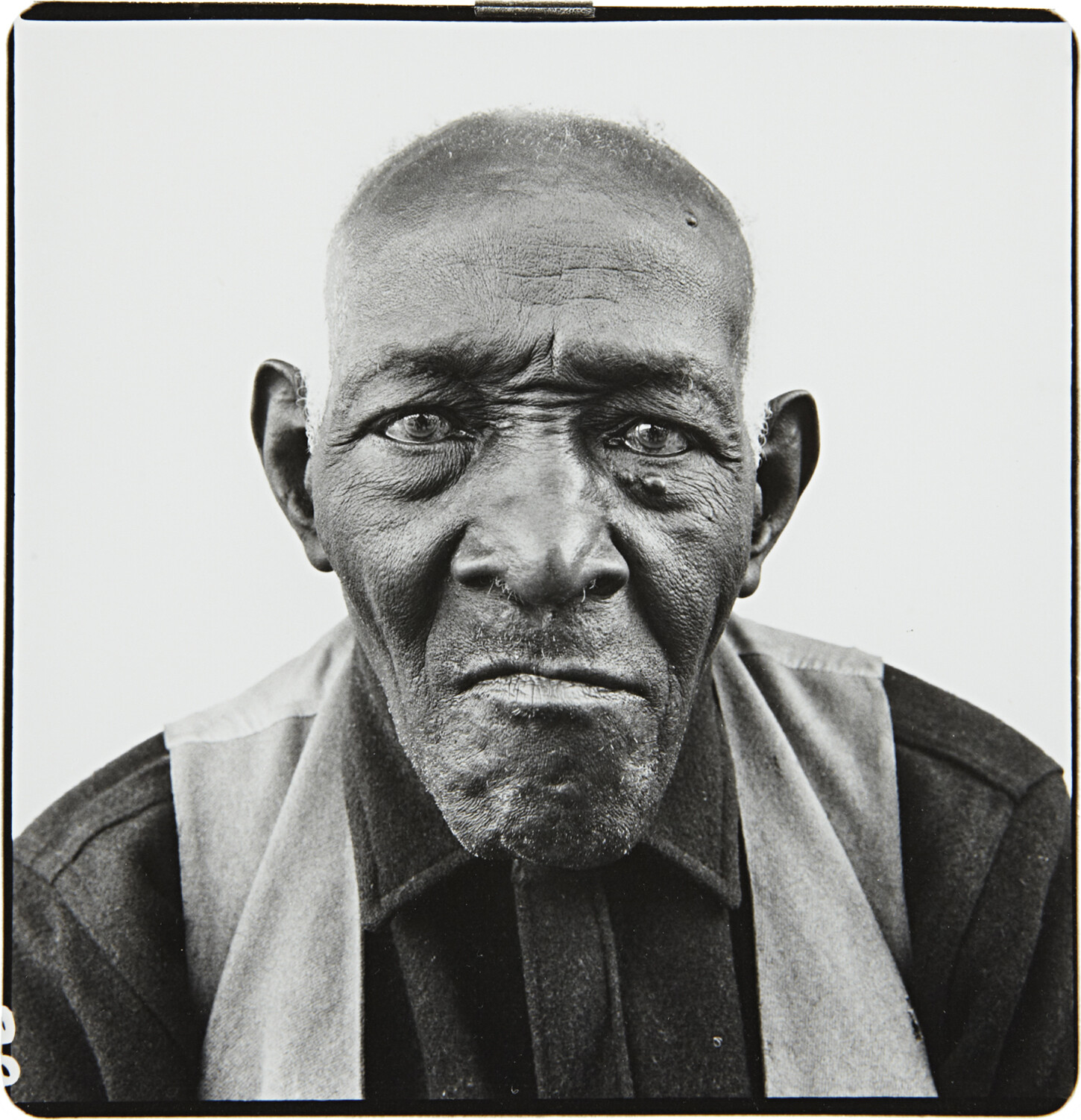

The “resistant objecthood” that grounds the performances in Lawson’s and Pfeiffer’s images unearths a deeper white anxiety at blackness’ lack of restraint, and its intemperate hostility to discipline. Lawson’s and Pfeiffer’s aesthetics interrogate the normative value of visibility and proffer a politics of visuality in which blackness at once appears and retreats. In their work, raced subjects cultivate a visuality of fugitive evasion, or, to borrow from Anne Anlin Cheng, they manifest “a disappearance into appearance.” Their images model spectacular opacity as a black visual practice that recedes into view.