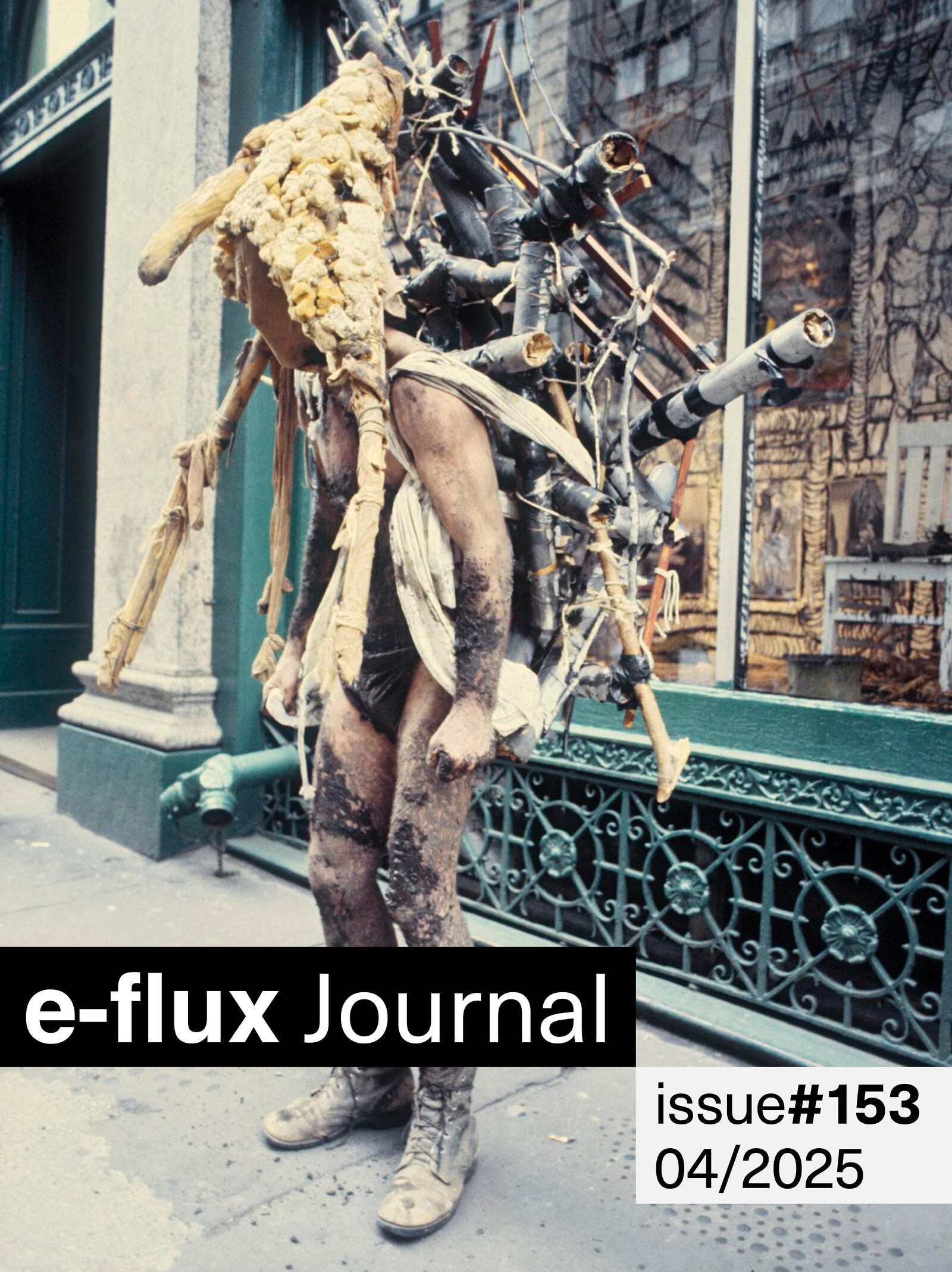

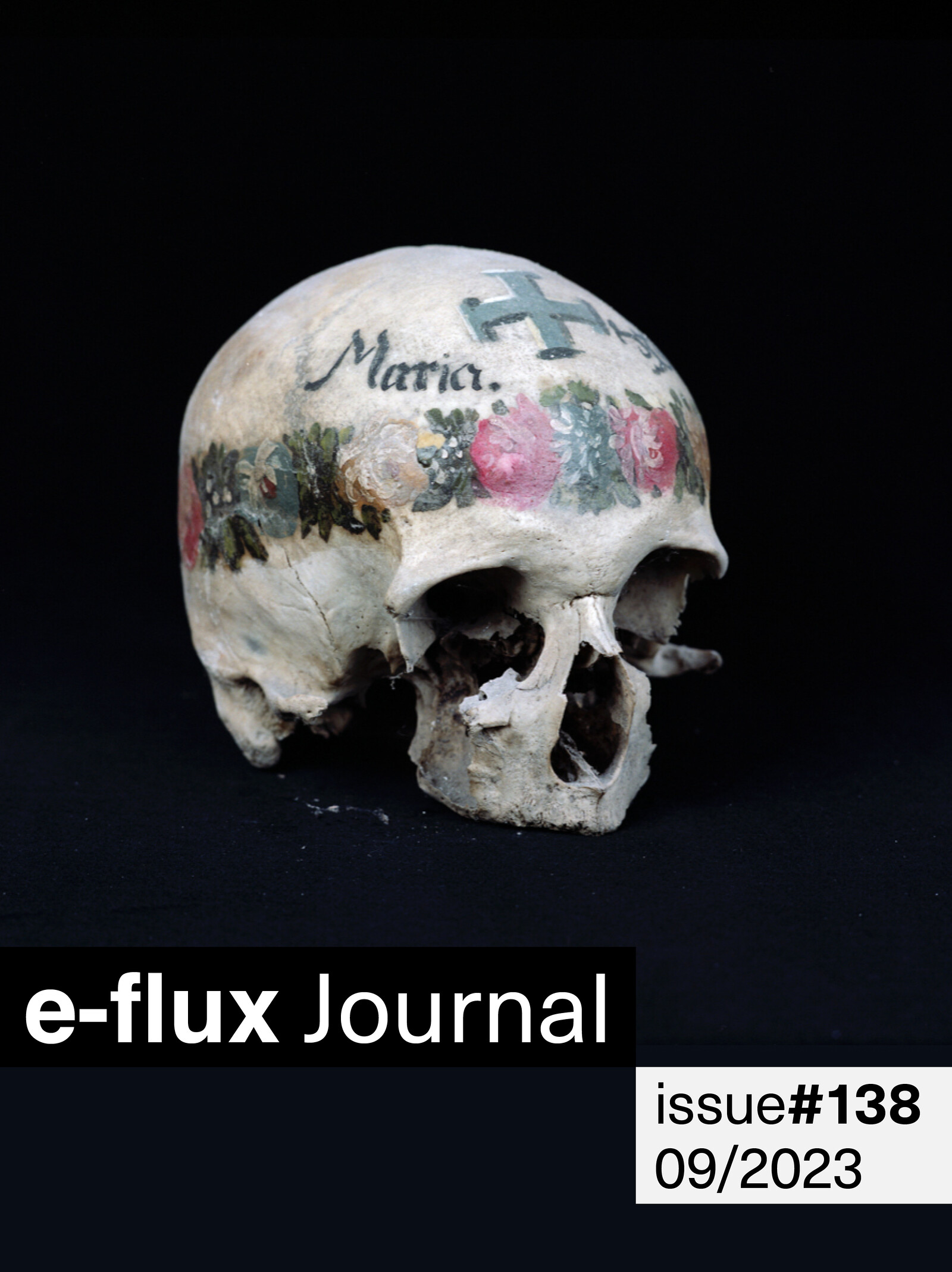

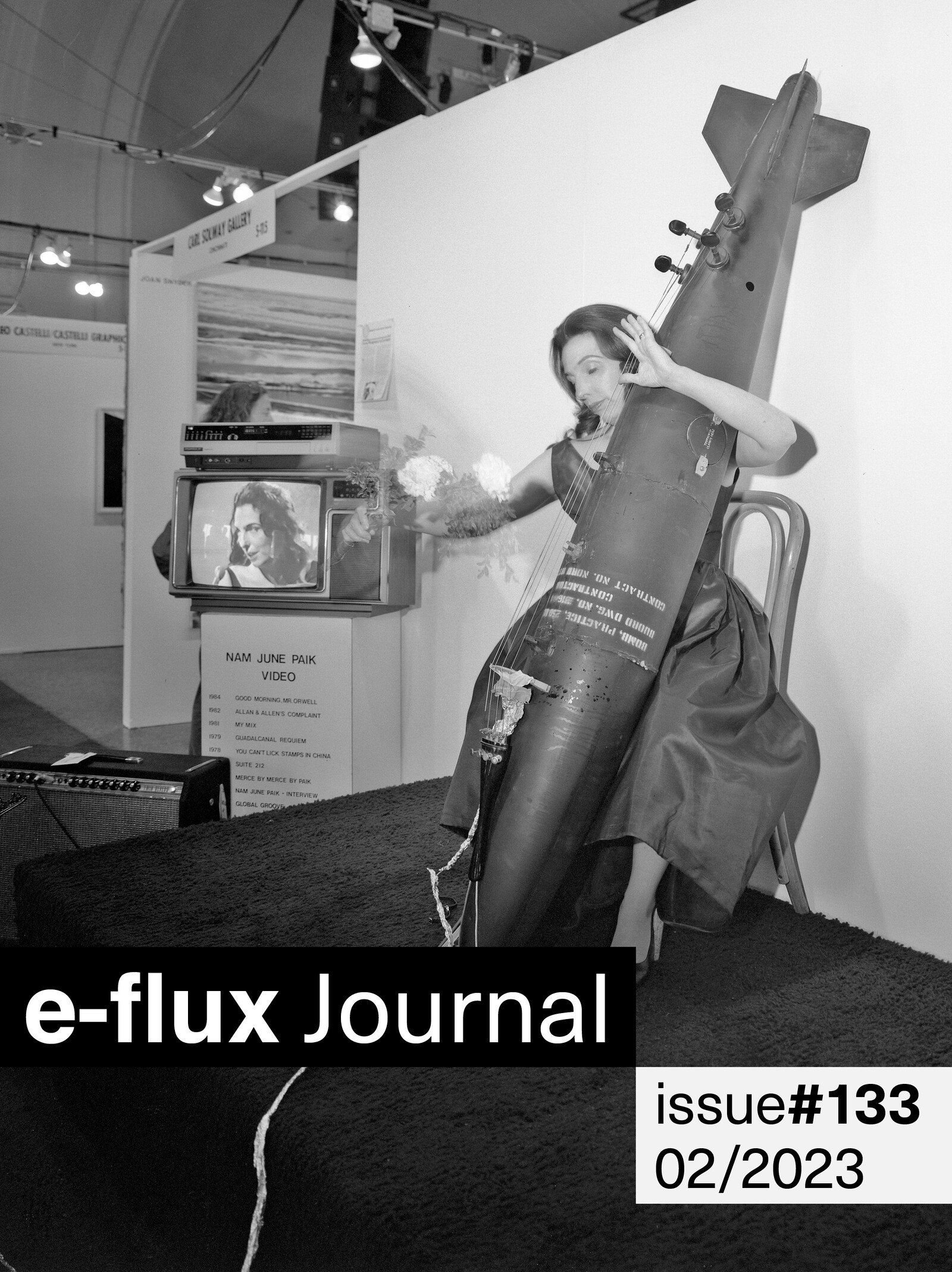

Wars can be waged in various forms, from cold to hot, from trade wars to psychological warfare to outright bombardment and genocide. The techniques available for negotiating unresolvable differences can seem endless. But it would also seem that the material of war’s underbelly is capable of a strange expressivity. In this issue, Mary Walling Blackburn takes on the genre of “trench art”—objects crafted from war’s detritus by soldiers addressing material or spiritual needs, or by prisoners or civilians reflecting on the circumstances of war and confinement. In their detailed making and decorative use, Blackburn finds a contorted, diagonal relation to fine art objects. If trench art often miniaturizes the psychic magnitude of war, what would a proportional relation look like, say, if the estimated millions of tons of rubble, human remains, and unexploded ordinance in Gaza caused by US arms could be materially reabsorbed as an “unholy amalgam” of trench art for US art collections, as collective burial and real consequence? If spent bullet shells, weapons, or other war detritus can become decorative trench art, artist Kim Jones’s Mudman on the issue’s cover demonstrates how the psychological trauma of war can transform into material for art.

A curious series of handmade signs started replacing commercial advertisements in some bus shelters near e-flux in the Clinton Hill neighborhood of Brooklyn over the last few weeks. Amidst the new US government’s breakneck pace of undoing itself, the signs’ cheerful colors, reminiscent of children’s crafts, and their calls to protect democracy and resist seem to inhabit a level of power surreal in its mismatch with that of Trump, Musk, and their cabal armed with AI engineers and turbocharged by historically unprecedented wealth. Amidst the near-absence of effective opposition from the stunned onlookers of more organized and powerful bodies in the Democratic Party, labor unions, and civil society, perhaps this does not bode well for the outcome. Then again, maybe this is how a new form of opposition begins.

The conspicuous presence of human growth hormone and ill-fitting suits worn by tech-billionaire CEOs in the front row of Donald J. Trump’s presidential inauguration last month speaks volumes about the deep ties between the disruptive ideology of the tech sector and far-right movements in recent decades—a partnership now formally entering the White House. The way disgraced New York City mayor Eric Adams was relegated to a back room after receiving a last-minute invite to the inauguration only adds to the displacement of traditional agents of governance to make room for the new “globalists.” Neoreactionary thought has been particularly influential, appealing to young provocateurs in art and tech turned on by its brand of futurist extremism and targeted anti-humanism spotted with various illiberal tendencies masquerading as pronatalism, market nationalism, and so on. In this issue, Yuk Hui notes that vice president J. D. Vance’s close association with Dark Enlightenment figures such as Peter Thiel and Curtis Yarvin has taken their abject provocations to a new extreme. Hui revisits his 2017 e-flux journal essay “On the Unhappy Consciousness of Neoreactionaries” to analyze how this fitful thrashing of US empire clings to the spoils of globalization while also buckling under its consequences, deepening its unsustainable contradictions.

In January, Donald Trump will begin his second term as the president of the United States. His first term and his campaigns have been defined by the extreme and effective loosening of the constraints of “reality” on previously unimaginable levels of power. His critics are often hampered by confusion over whether his policies are guided by any intentionality or foresight. His actions mix transactional plays with intoxicating chaos, to an extent that last month multiple former high-ranking US military officials from his previous administration agreed that Trump is “fascist”—a sentiment likely circulating within the world’s most powerful military that he will soon lead again, at least nominally. But Trump’s radicality and pathological intensity in courting chaos threatens more than just military structure or policy, and is not only about the already fragile concepts of “truth” and “facts,” but about a much higher order where reality itself is structured. Developing literacy in this domain will be essential for geopolitics in the difficult years ahead.

Wars are never the result of just one man. And yet, today’s strongman leaders are emblematic of the ideological and existential rot that hides within state systems, behind the promise of an ultimate showdown of all against all. It is well known, perhaps within Israel more than anywhere, that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been indicted on multiple criminal charges of bribery, fraud, and breach of trust. These charges were not handed down by the Palestinians, by Hamas in Gaza, by Hezbollah in Lebanon, or by the Houthis in Yemen. He will not stand trial for corruption by the Islamic Republic of Iran or the United Nations, nor by the International Criminal Court (which has issued an arrest warrant against him for war crimes and crimes against humanity), nor by South Africa (which has formally accused Israel of genocide in the International Court of Justice).

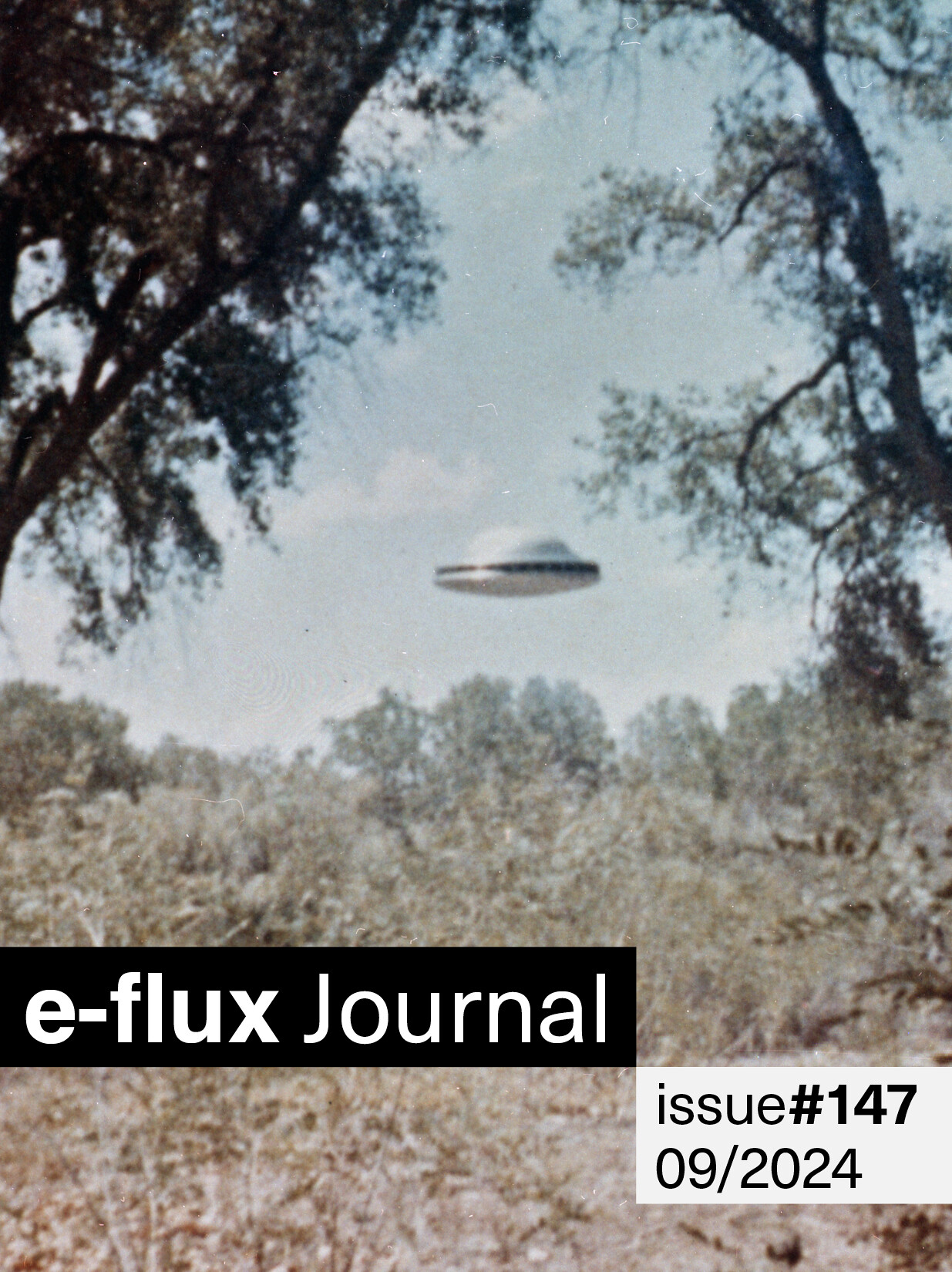

In this issue of e-flux journal, Trevor Paglen begins his three-part essay on how US military psychological warfare techniques were a historical predecessor to today’s AI-driven social media trained to identify emotions and exploit affects. Telling the story of Richard Doty, a counterintelligence officer who deliberately spread disinformation about extraterrestrials as cover for military operations, Paglen identifies a key tenet of the US Army Field Manual: it is easier to deceive someone by reinforcing their preexisting beliefs than to change those beliefs. Behind the outlandish but well-documented example of UFO sightings lies a chilling warning that the creation of an entirely new reality is accomplished not through coercion but through the tactical use of affirmative encouragement.

Under the right conditions, each day contains two brief moments when the rising or falling sun hits at an angle so precise it arrests the eye. In this issue of e-flux journal, Oraib Toukan shows that there is more to what filmmakers and photographers call the “golden hour.” The unmistakable light of a brief interval also reveals things exactly as they are. In this time of Gaza’s devastation, Toukan explores the power and limitations of words and images in conveying the depth of Palestinian grief and dignity amidst what appears to be an ongoing ethnic cleansing. The grounding concept of turbeh (soil) emerges as an axis for knowledge and justice, urging readers to look beyond the surface and into the soil grain of images.

Last month, Documenta 16’s Finding Committee resigned en masse following the resignations of Bracha L. Ettinger and Ranjit Hoskoté. In his written resignation, Hoskoté explained the high irony of being accused of anti-Semitism for having signed an online petition against an event hosted by the Israeli Consulate to India in 2019. The event drew an alliance between Zionism and Hindutva, the Hindu ultranationalist ideology that was inspired by European fascism and that proposed Hitler’s policy for Jews as a method for dealing with Indian Muslims. Yet Germany’s culture minister, Claudia Roth, denounced the obscure 2019 petition Hoskoté signed as “clearly anti-Semitic” for describing Zionism as “racist” and Israel as a “settler-colonial apartheid state,” threatening to withdraw state funding if Documenta didn’t cut ties with Hoskoté.

The illogic of exclusion and exception is seductive. Perhaps we will all know ourselves better when we advertise our own place in the world by taking sides with regimes that masquerade as fixed identities and project illusory strength while actually being irreparably fragmented from within, just like we all are. The oppressed, on the other hand, know that a much larger struggle can only be sustained by distinguishing faithful from false witnesses among their own ranks as well as the enemy’s. True identity is forged by how we choose to bear witness, by what endures and grows in meaning as it is transmitted.

In this issue, Charles Mudede proposes that Octavia Butler brought us a viable theory of quantum movement. Who is capable of moving through time to haunt other people in other places and other times, and in which direction? Paradoxically—and there are many paradoxes—just as the hurt have been hurt, the dead can only be dead, and are for that reason no longer able to move forward in time to haunt us. We, however, are alive in our own time, and we feel pain on their behalf. It is we who reach out from the future—our present—to haunt them in the past. We are in fact the zombies of the already dead, mirrors of our own regrets, just as we are presently haunted by messengers from a future time warning us to not repeat what they know will not end well.

Often it seems like we are facing so many endings that we can only be living in the end times—a self-annihilation whose inevitability even appears deliberate. From climate projection to daily news, much of the apocalyptic tone we encounter has an almost celebratory character, as if the end times were more of an ideological construction than a common observation. Certainly a lot of it is macho clickbait or political brinkmanship, and in some cases actual worlds ending. But it also carries a stranger imaginative character in the absence of any significant political imagination by traditional standards. Indeed, taken as a literary tool more than a documentary one, perhaps there is more to the end of the world than we thought.

Part of what makes interviews so engaging to read is that they presume to share ideas on the fly, in a social setting and in the world. In comparison, written essays feel like constructed machines, lean and airtight with beginnings, middles, and ends. No wonder interviews, as a whole, seem a bit decadent in their procrastinatory pleasure. It’s like they catch interlocutors off guard when they should be doing something more serious. Interestingly though, the informality of speech is also a ruse, and a formal challenge for those who prefer to construct words and ideas methodically, because things sometimes spill out that wouldn’t be disciplined into more structured writing and thinking.

In this issue, Xin Wang details the haunting of China’s contemporary art by socialist-realist pedagogy from the Soviet Union. Perhaps even more significant than this line of influence is its near-total occlusion in Western accounts of China’s avant-garde lineages, no doubt related to Clement Greenberg’s assaults on Soviet socialist realism for epitomizing kitsch. Following Greenberg’s lead, Western scholars may have attempted to be generous by elevating works above lowly pictorial origins, but in doing so, they cleaved them not only from their key influences, but also from a range of formal innovations and attitudes specific to socialist modernity—a version of modernism that continues to persist through its negation, haunting artworks up to today …

In this issue, Boris Groys charts the self-transformation of the working class through labor itself. Workers’ bodies, through their own labor, become spiritualized—artificial forms of their own creation. Since modernity, the working class, held up as a universal whole, has practiced “secular ascesis,” even if by exploitation and oppression. And where does this spiritualized dimension of the working class manifest itself? As art.

In the first e-flux journal issue of 2023, the Ukranian researcher and curator Kateryna Iakovlenko points our eyes at images of forests. The first is from the site of a mass grave outside Izium, a city on the Donets River in eastern Ukraine. The bodies were gone by the time the photo was taken; instead, the photographer shows medics and the surrounding woods. Another is a nineteenth-century photograph of a forest in Tasmania picturing lush trees, which on close examination conceal colonizing British officers. A more recent Instagram photograph shows a feminist Ukrainian Army volunteer living, with others, among the trees they are protecting. A final photo was captured by an occupying Russian Federation soldier’s camera moments before his death outside Izium’s woods. His body remains out of view; his unambiguous vantage point of the exploded forest landscape remains.

In this issue of e-flux journal, deep glances at the past hope to make sense of the present by diving into history’s original abysses and early promises. Mi You brings us a refreshingly constructive analysis of this year’s documenta fifteen, its curators, its intended organizational structure, and its audiences. Olga Olina, Hallie Ayres, and Anton Vidokle chart suppressed, banned, and otherwise disappeared languages in a resource that sprawls over geography and time from 1367 to today, showing an ongoing process of erasure and survival that corresponds with the rise of nation-states.

In this issue of e-flux journal, Carolina Caycedo explains that so many climate activists in South America are murdered by the state that their friends and families have coined a new term for this loss: the dead aren’t killed so much as they are “sown,” like seeds. Their legacies are a source of abundant energy and knowledge to be used in continuing struggles against the collusion of extractive corporations and necropolitical states.

Chances are that in the last couple years, your life has been turned upside down by a pandemic, a war, an economic meltdown, or some combination of these. And you may feel that whatever you were lucky enough to avoid may already be on its way to you. As the coming years are sure to bring more uncertainty, maybe it’s time to prepare. Buy a small armory and move into an underground bunker? Blame foreigners or neighboring countries? Attack each other online? Let’s try instead to consider how our basic needs are met, as the individual and collective bodies that we are.

In this issue, Asia Bazdyrieva offers a broader picture of Ukraine’s significance as a biopolitical resource for Western European appetites. In Ukraine’s operational capacity as Europe’s “breadbasket,” a colonial imaginary unfolds that sees the country’s human, agricultural, and material resources as inert—ripe for extraction by a conqueror who can release their inexhaustible transactional benefits.

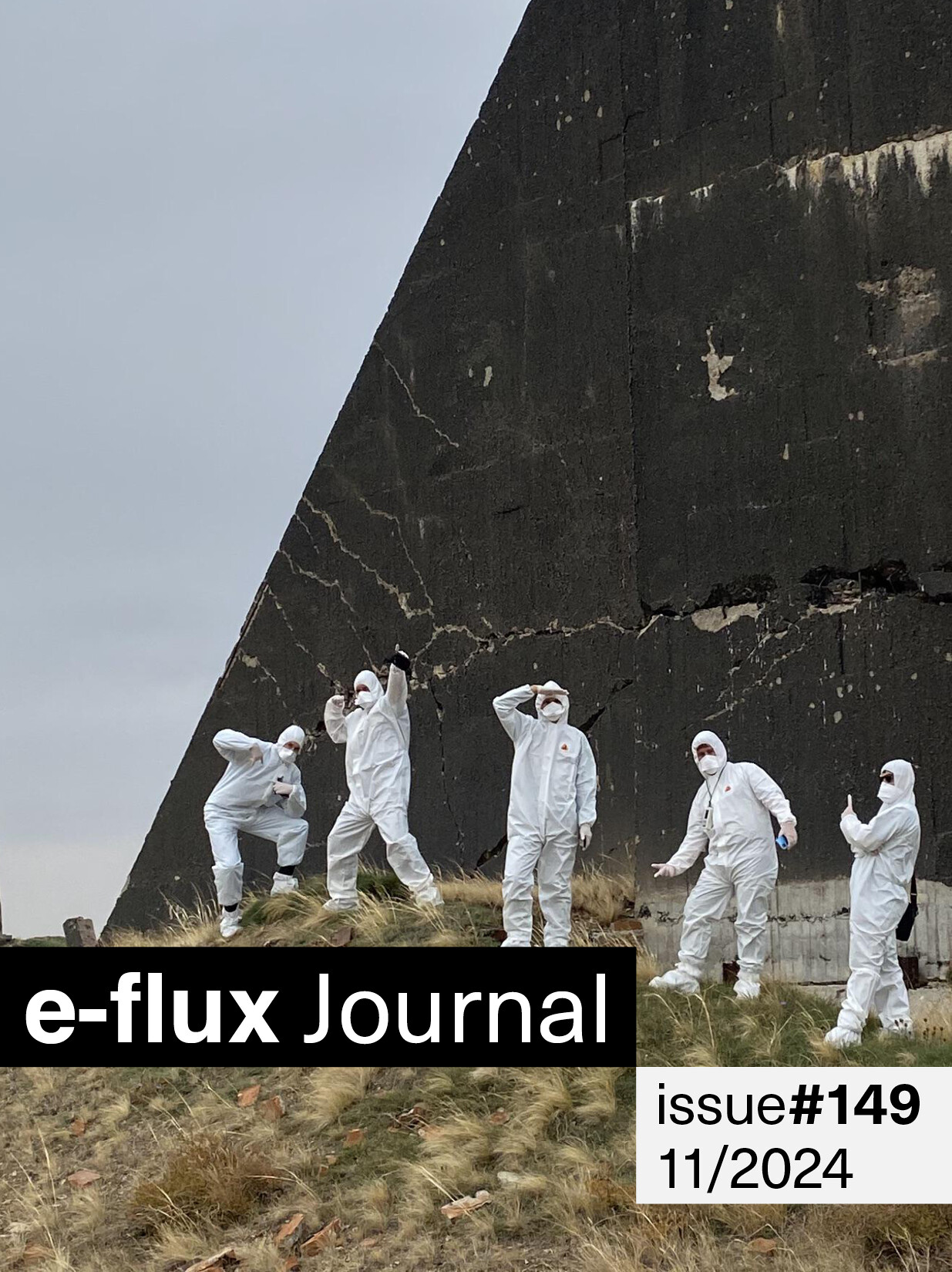

It’s unclear how many people still alive today can remember feeling the strange, warm rains that fell over the riverside city of Pripyat on the Ukraine-Belarus border in late April 1986. Pripyat was built in 1970 to serve the nearby Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, dedicated to harnessing the mirnyy atom (“peaceful atom”) for the Soviet Union. For the past thirty-six years, Pripyat and a surrounding exclusion zone of inconsistent bounds bridging swaths of today’s Ukraine, Belarus, and a bit of Russia have been off limits to most human beings.

A couple weeks ago, the world turned upside down again. Dnipro has been bombed again, but not by the Nazis. It’s like a bad dream one can’t wake up from: while thousands of people are being killed in Ukraine and millions are being displaced by the Russian army, nobody really seems to understand the reason or goal of such violence. While Ukraine is being bombed and destroyed, the social fabric of Russia and its economy are disintegrating under sanctions and martial law, and what is rapidly emerging is an isolated, impoverished, fascist state propelled by a death drive.

In the first e-flux journal issue of 2022, Bifo points out a recent social protest movement in China known as tangping (躺平, “lying flat”), in which young people increasingly opt out of the pressure to overwork by taking low-paying jobs or not working at all. In the US, “the Great Resignation” has been the name for four and a half million American workers who left their jobs at the end of 2020. But Bifo reminds us that “resignation” also means re-signification—a new meaning given to pleasure, richness, activity, and cooperation that may unveil a previously hidden egalitarian and frugal sensitivity following the exhaustion of the Western geopolitical order.

Two women sit at a sidewalk cafe in Manhattan. There are others around: suited bros poring over a spreadsheet, a possible fashion blogger, generally well-dressed white people. The women engage in dialogue and play a game. They talk Platonism, Nietzsche, femmunism, and also traps. The initial point of the game is to decide who has partaken in a particular sexual act, and who has given it or been taken by whom. As they speak, the women, in a dialogue written by McKenzie Wark, create a trans-for-trans space for communication, for a world both part of and separate from the cis one. As one woman tells the other, “They think they know our little secret, but we have information about being that they will never know.” As she says earlier, “We turn the cis gaze back on itself.”

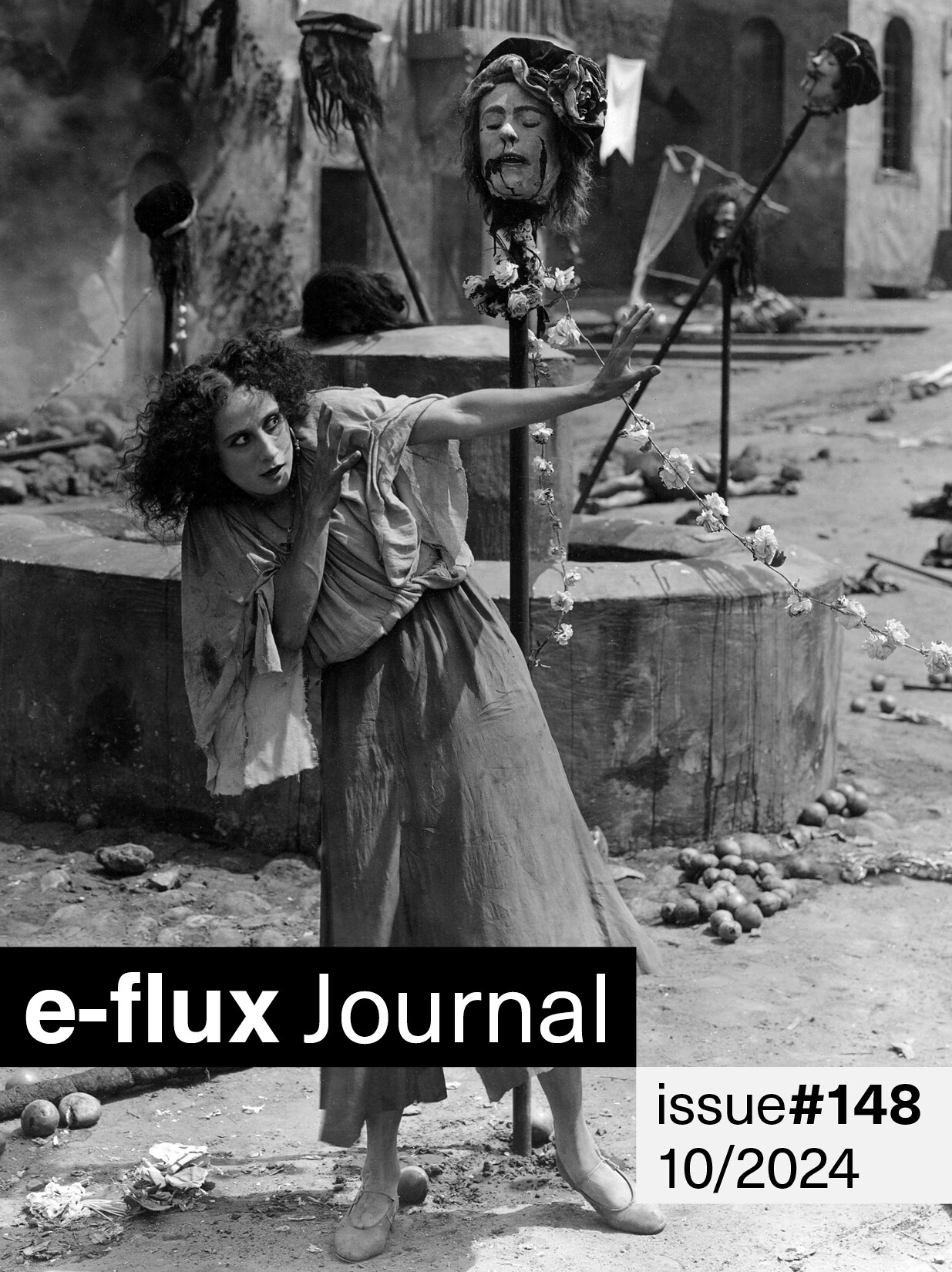

It is now October, when the veils between worlds become thin. In this issue, there are human worlds and more-than-human worlds, and the university worlds, world wars, and art worlds that cross between them. Tam Donner plumbs the world we live in. Have you heard the one where universities give out honorary hoods to painters and warmongers alike? Take a look at the class pictures. Andreas Petrossiants follows the lead of Mount Etna, Europe’s oldest active volcano, where Pasolini may have seen a stage—or a screen—on which to feature the volcano’s ability to communize time, showing “linear, European time for the cruel joke of modernity that it is.”

As we step out of our homes this September to go back to school, go back to work, go back to traveling, we might pause for a moment to look back into this home, this peculiar chamber of private life that, in one way or another, we couldn’t exit for some time. Perhaps the outside world appears strange, menacing, or deceitful. Maybe it was from staying inside for too long.

We have never completely understood poetry. As a contemporary art publication, there’s no shortage of affection, admiration, or affinity for poetry, and e-flux journal has certainly published a few memorable poems over the years. But it always felt like a stroke of luck or a gift from the ether when someone brilliant would send us a poem. You won’t be surprised that this didn’t happen often. But now is the time to change that, and we’re honored to welcome Simone White as e-flux journal’s first ever poetry editor. Simone is the author of the collections or, on being the other woman (forthcoming from Duke University Press), Dear Angel of Death, Of Being Dispersed, and House Envy of All the World, and lives in Brooklyn. We’re so glad that she’s joined us.

On the occasion of the Taipei Biennial 2020 and together with the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM), this special issue of e-flux journal will also be available to read in Chinese in 2021. Titled “You and I Don’t Live on the Same Planet,” the issue deals with an increasingly pressing situation: people “around” the world no longer agree on what it means to live “on” earth—to such a radical extent that the foundational material and existential categories of “earth” and “world” are profoundly destabilized.

In this issue, Alessandra Franetovich and Trevor Paglen discuss Orbital Reflector, Paglen’s reflective sculpture launched into low-earth orbit as a satellite. Housed in a small box-like structure, the lightweight reflective material of the sculpture was meant to deploy and self-inflate like a balloon and reflect sunlight towards earth, making it visible to our eyes as a nearby artificial star. Unfortunately, at the critical moment of the sculpture’s release in 2018, the US government was on shutdown, with all agencies held hostage in order to force Congress to fund Trump’s gigantic border wall between the US and Mexico. There was no way to release the mirror.