Boris has been very close to artists ever since his student days and, while I hesitate to think of him as an art historian or a curator, his insight into art and its practitioners is unprecedented for a theoretician. Maybe this is why the Gesamtkunstwerk Stalin book he gave me years ago was so important for me in seeing the relationship between the incredibly complex trajectory of the Soviet avant-garde and the brutal velocity of dictatorial power: the total work of art that the USSR briefly embodied, and where I came from.

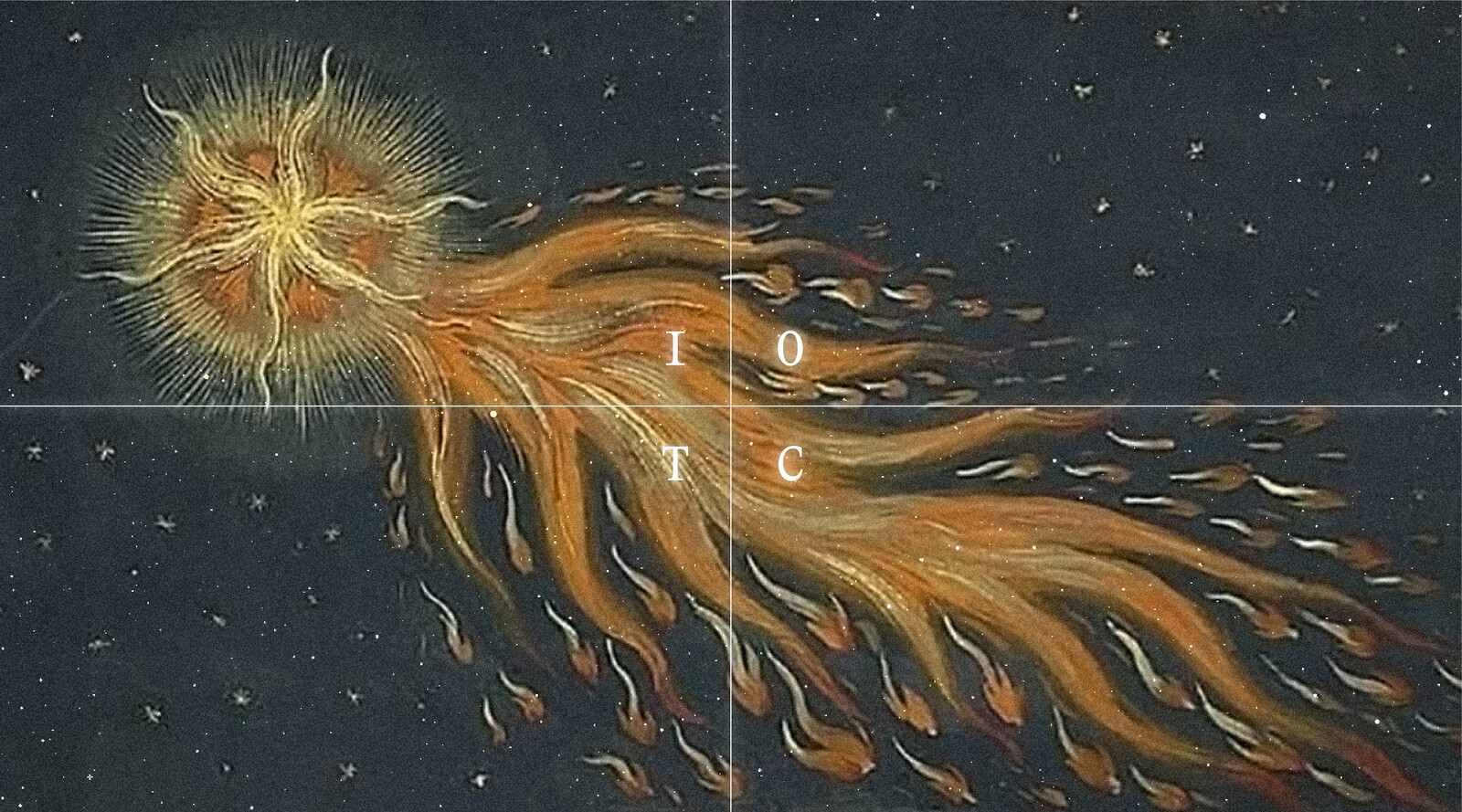

According to Evald Ilyenkov, the dialectic process must have no beginning and no end; it must be infinitely circular. Such an infinite circulation presupposes that at the end of every cosmic period, every humanity takes the decision to explode itself and thus let the universe start a new cosmic period. Here dialectical materialism is inscribed not merely into historical materialism but into the symbolic exchange between universe and humanity, between nature and spirit.

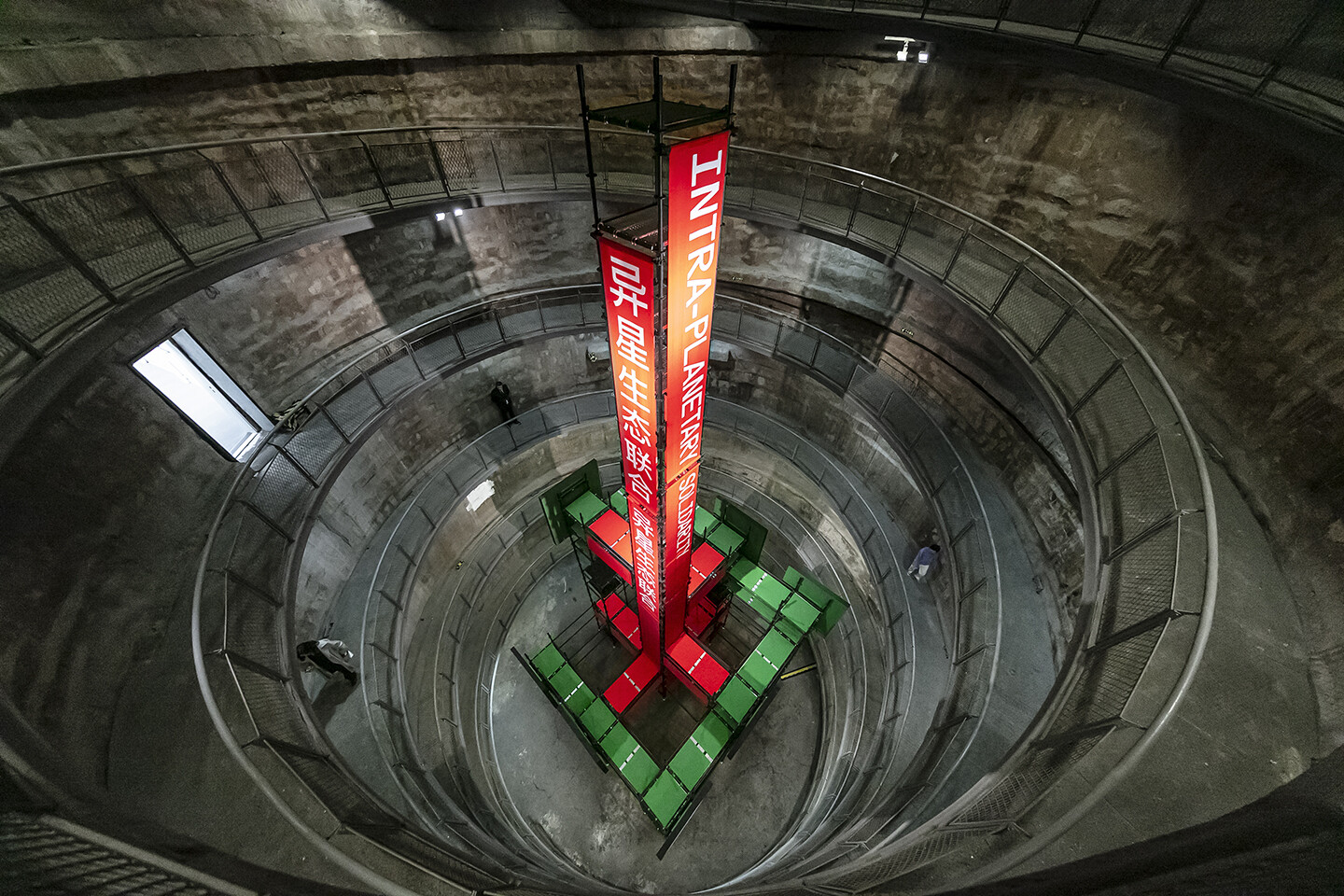

Launch of e-flux journal issue #142: Cosmos Cinema

In the coming decade, humans will likely become an interplanetary species by creating permanent settlements on the moon and Mars. This endeavor clearly reproduces a terrible colonial and imperialist legacy that shamelessly speaks of martian “colonies” and a new generation of space “pioneers.” To challenge these environmentally disastrous space missions and the neocolonial, imperialist models they plan to export into the cosmos, we terrestrial beings need to alter the very foundations of our exo-ecologies in the making.

An AI image generator was given the prompt “salmon swimming in a river.” It produced several puzzling images of similar composition, each of which shows what is unquestionably salmon in a stream of water. However, none of the results matched the familiar image of a legendary piscine hero swimming full-bodied against the current. Instead, they all depicted a fraction of a salmon, a fillet of salmon, its pink flesh ready to be seared or made into sashimi. In AI’s defense, the algorithm did not interpret the prompt incorrectly. All the right elements are there: this is not a pig in a volcano. Yet it all appears wrong to human eyes.

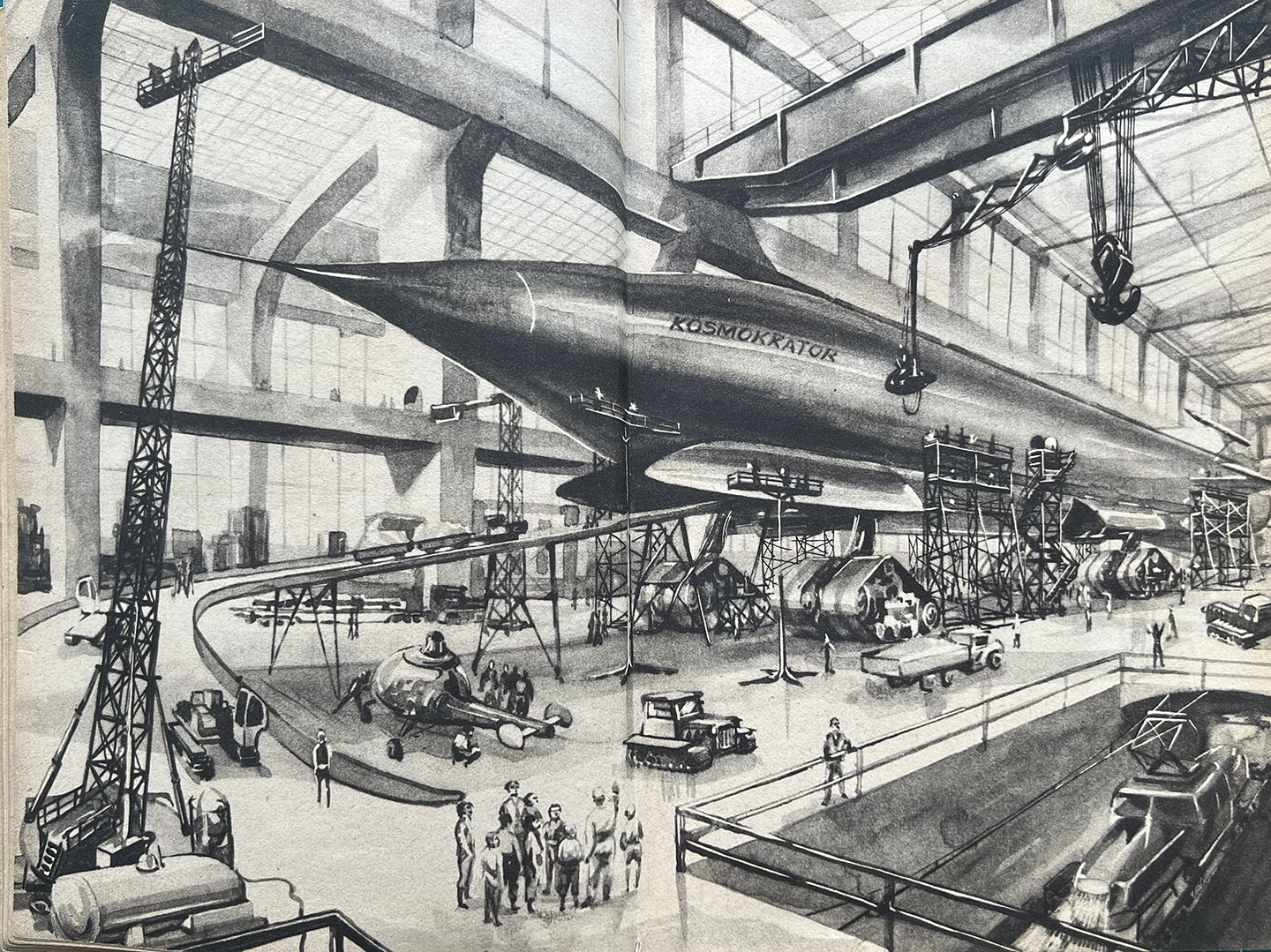

Methodologically speaking, it might be said that all of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s installations are in some way or another connected with a special structured experience of space, echoing the transformations of the starry sky. But there is one installation in which the sky also becomes the center of gravity. We are talking about perhaps their most famous installation, The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment, first shown in the Kabakovs’ Moscow studio in 1985. The viewer is presented with a room in a communal apartment that has been sealed off by investigators. The room’s resident has, with the help of a homemade device, escaped Soviet reality and is hiding in the sky.

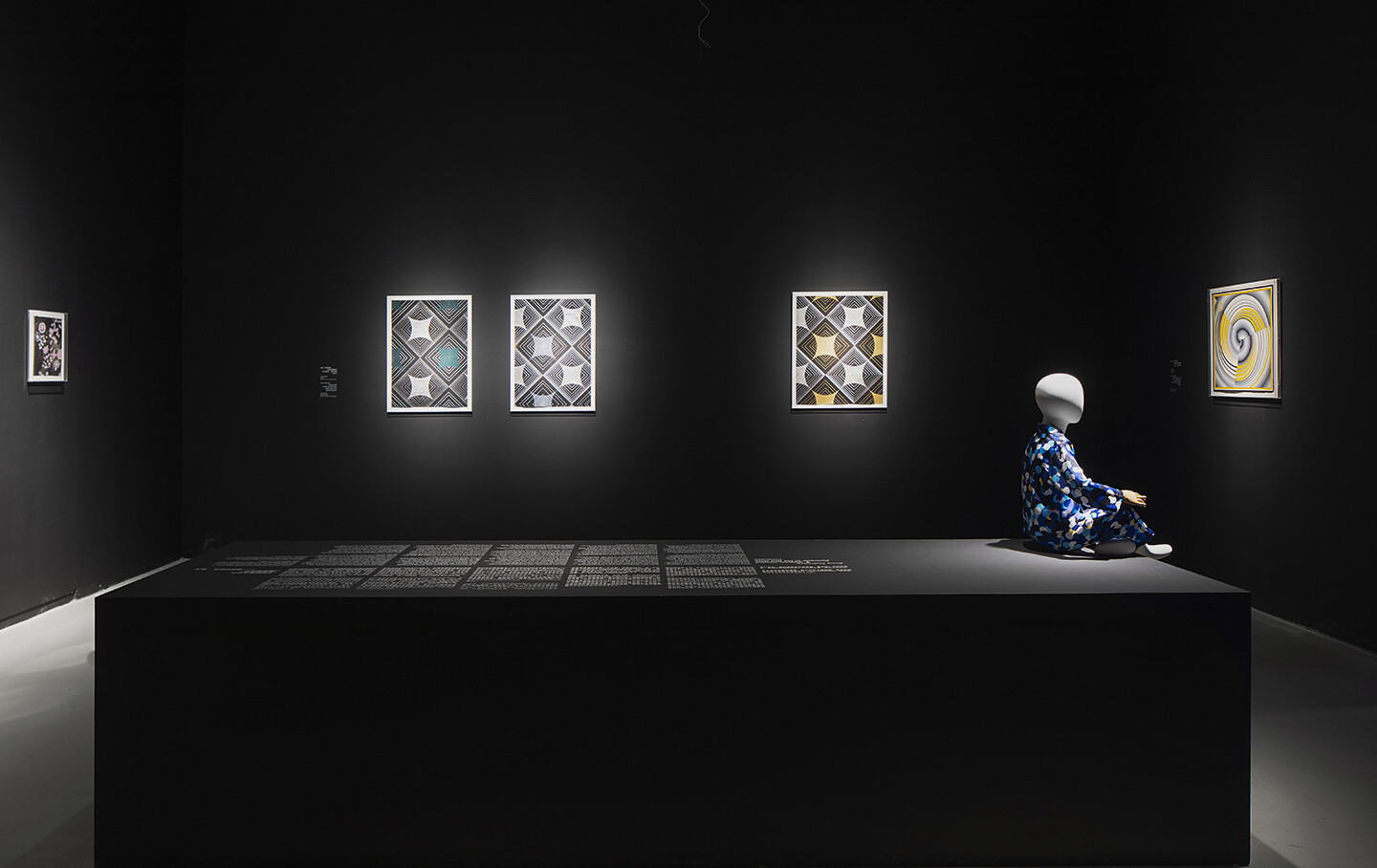

Art has from the very beginning been deeply intertwined with reflections on our position within the cosmos and what this might teach us of mortality. My goal with “Cosmos Cinema” was to consider how these themes are addressed by artists working both historically and today, and to place these artists into new sets of relations.

Andreeva’s cosmos is a place not to be conquered technologically but to be imagined on its own terms. In the tradition of Russian cosmism, with its utopian and technically unspecific dreams of resurrecting all the dead fathers buried on earth and resettling them on distant twinkling planets, we might say, borrowing from Robert Bird, that she is cosmic-minded, rather than space-race minded.

New York reception for 14th Shanghai Biennale: Cosmos Cinema

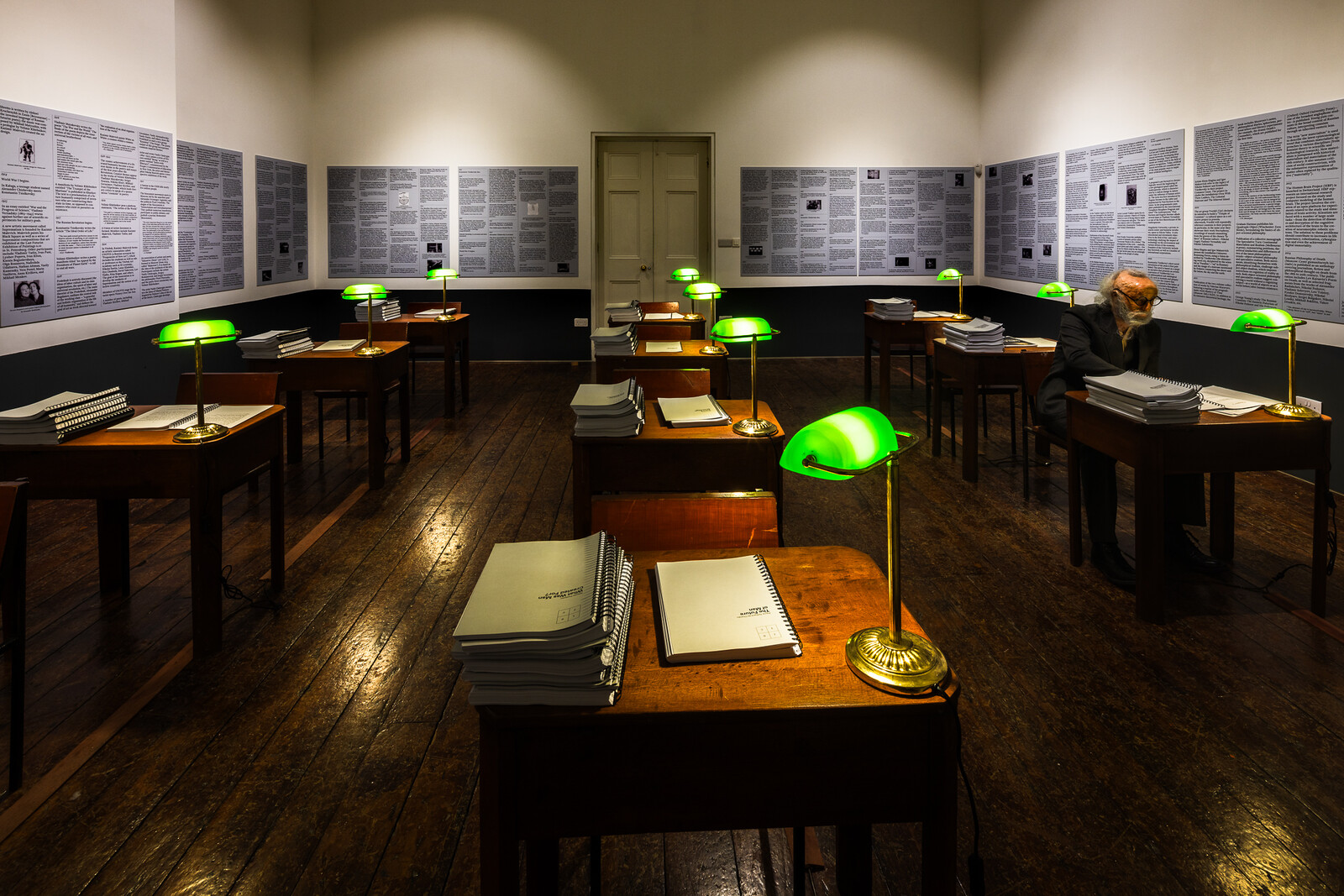

It was only natural that hope for survival was directed towards the museum system. After all, like art objects, humans are only particular material bodies, which can be kept intact and/or repaired and restored if necessary. The State took over the function that had earlier been fulfilled by God and Church. The State was not only responsible for the well-being of the living population but also for its immortality. This care was delegated to the curators.

When we speak about cosmic flights and the exploration of space today, we have in mind a dynamic model of technological progress. This dynamic model of progress implies that what we’re doing now in cosmic space will be continued and further improved by the next generation, and so on. The cosmists did not believe in this model. Their questions were along these lines: Why should we be interested in progress if we don’t stand to gain anything from it? If my generation contributes something to cosmic space, how can I benefit from it? I remain mortal, and I remain eternally indentured to progress. I live now—and not in the future. If progress is defined by a dynamic directed towards the future, everyone is yoked to progress, and every generation fast becomes psychologically and physically obsolete.