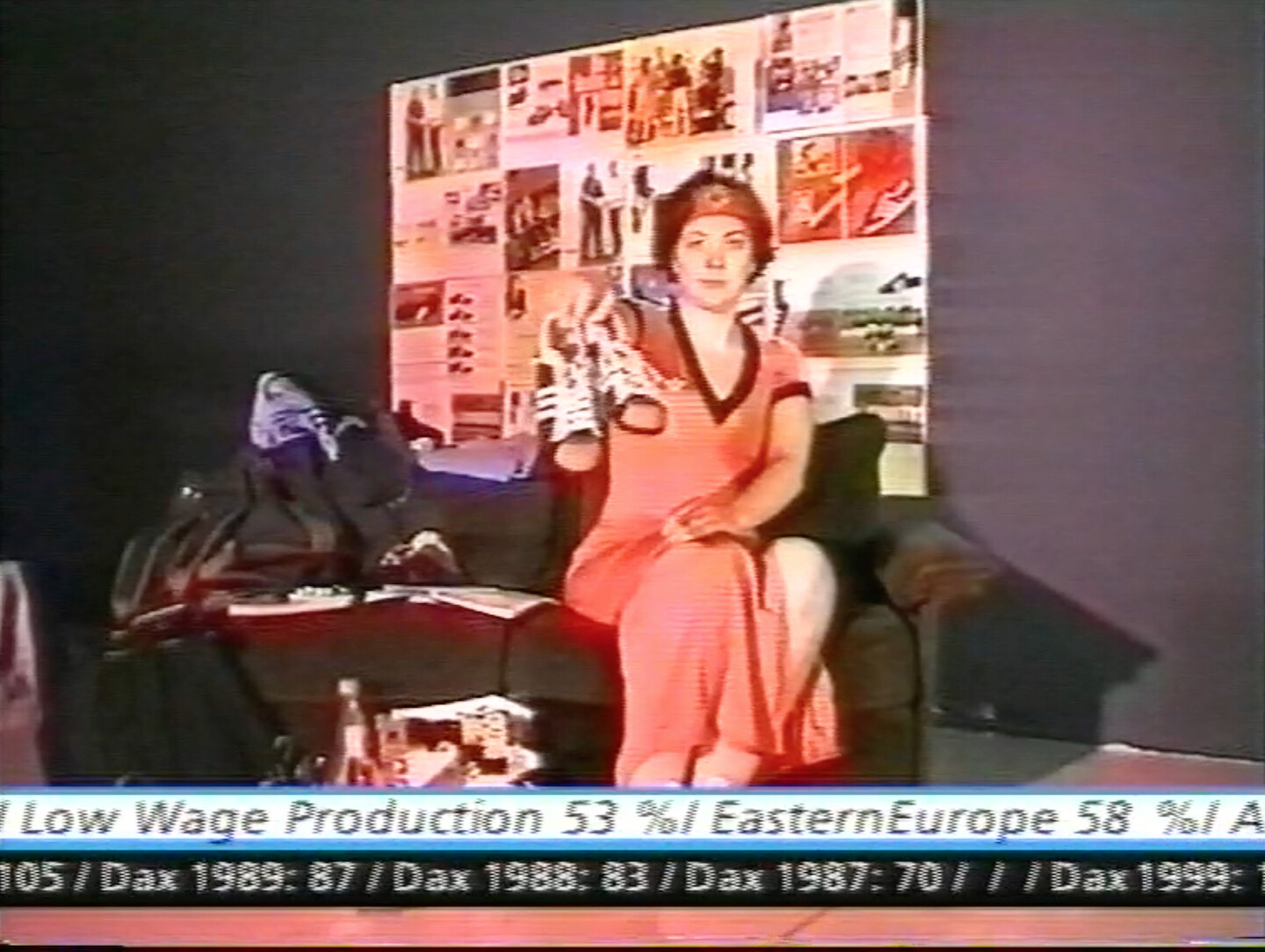

No longer content with their traditional role, artists in the nineties became actively involved as critics, mediators, and organizers, exploding the (art) system’s rigid division of labor. Instead of pursuing individual creative achievements, they devised various strategies of collective and collaborative work, in record labels, groups, bands, temporary project-based coalitions, or creative contexts established for the longer term.

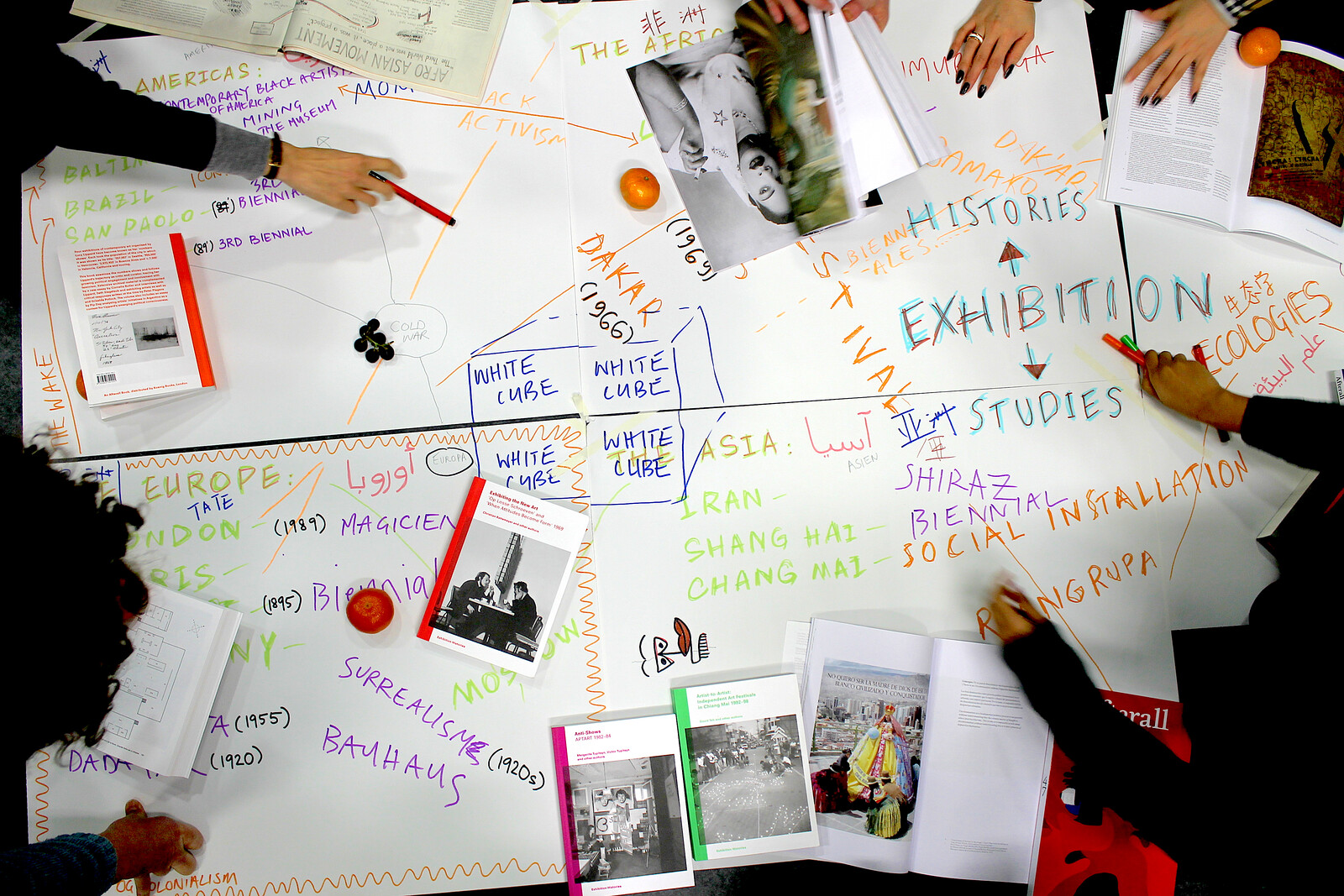

Okwui Enwezor’s Triennale articulated the challenges that globalization—and the movements of denationalization, decentralization, and de-hierarchization that arose from it—posed to the writing of modern and contemporary art history. Paris and its “excess of cultural capital” constituted, in Enwezor’s eyes, a fertile ground for revisiting the ethnographic model of otherness and reviving certain lessons from cosmopolitanism in the context of a tense cultural landscape.

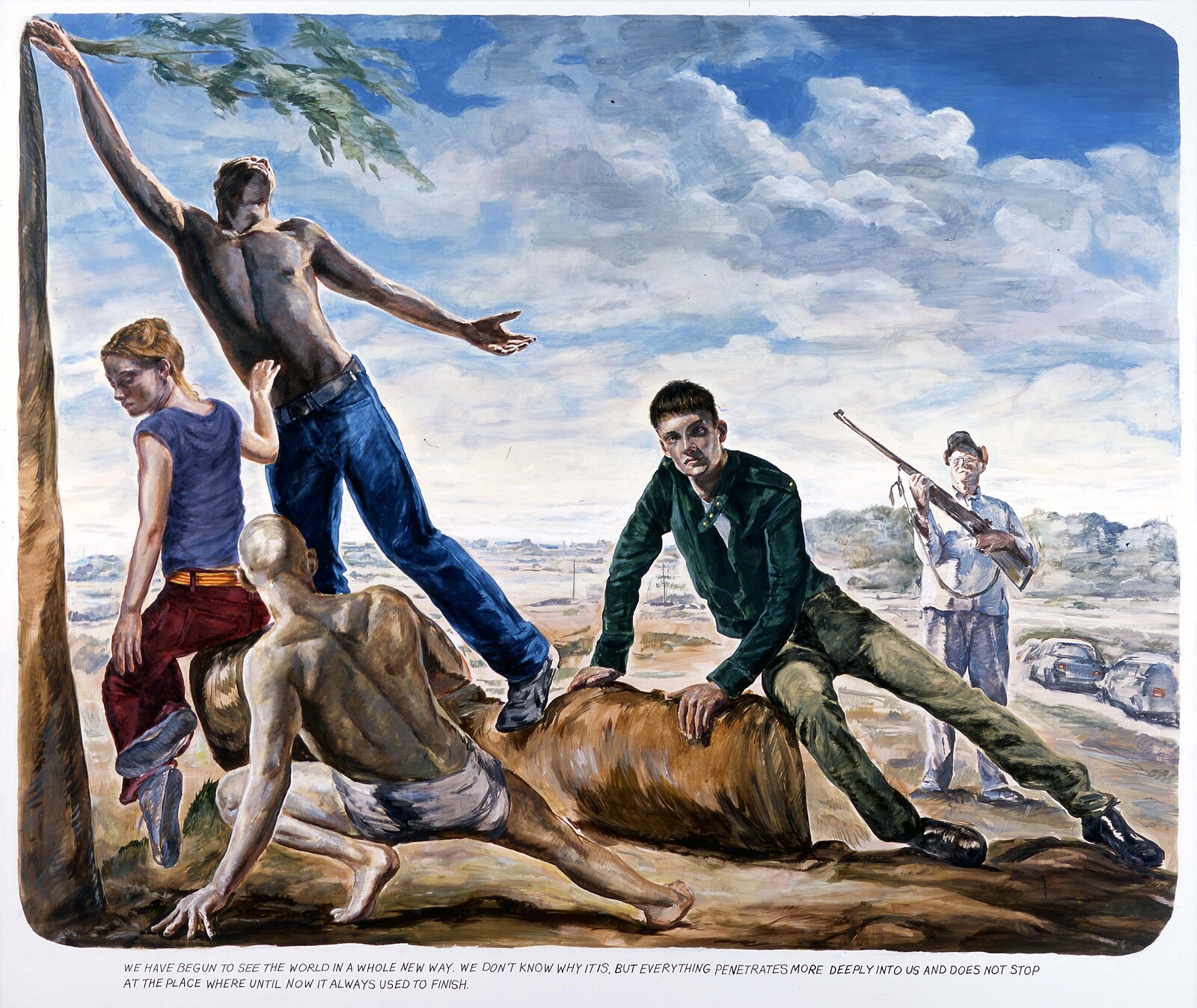

It seems unlikely that the racism (the unfair judgment of the work and experience of African curators) will go away. The trenchant pessimistic attitude that Africa will never develop its own museums is evidence of that. Prior to his death, Okwui Enwezor himself was foggy on the issue of whether to shift focus to exhibitions on the African continent, preferring to curate and write for institutions in Euro-America. Perhaps even he had difficulty avoiding how the evolutionary logic of racist pseudoscience has passed down a belief that some art is more developed than others—a legacy we still have to actively confront.

Material Marion von Osten 1: MoneyNations