“It Would be Alright if He Changed My Name”: Maxime Jean-Baptiste with World Records

Given that for those myriad subaltern communities marked as structurally disposable, as incapable of (democratic) rights and the (responsible) exercise of freedom, “the fascism which liberal modernity and civil society have always required has never abided by this order’s mendacious separation of the political from the aesthetic,” how could one expect an art keyed to the operation of these structures, or grounded in the historical praxis of these communities, to conform to the artifice of such notionally separable strictures as those that divide aesthetics from politics, form from content, present from past, living from dead?

It seems unlikely that the racism (the unfair judgment of the work and experience of African curators) will go away. The trenchant pessimistic attitude that Africa will never develop its own museums is evidence of that. Prior to his death, Okwui Enwezor himself was foggy on the issue of whether to shift focus to exhibitions on the African continent, preferring to curate and write for institutions in Euro-America. Perhaps even he had difficulty avoiding how the evolutionary logic of racist pseudoscience has passed down a belief that some art is more developed than others—a legacy we still have to actively confront.

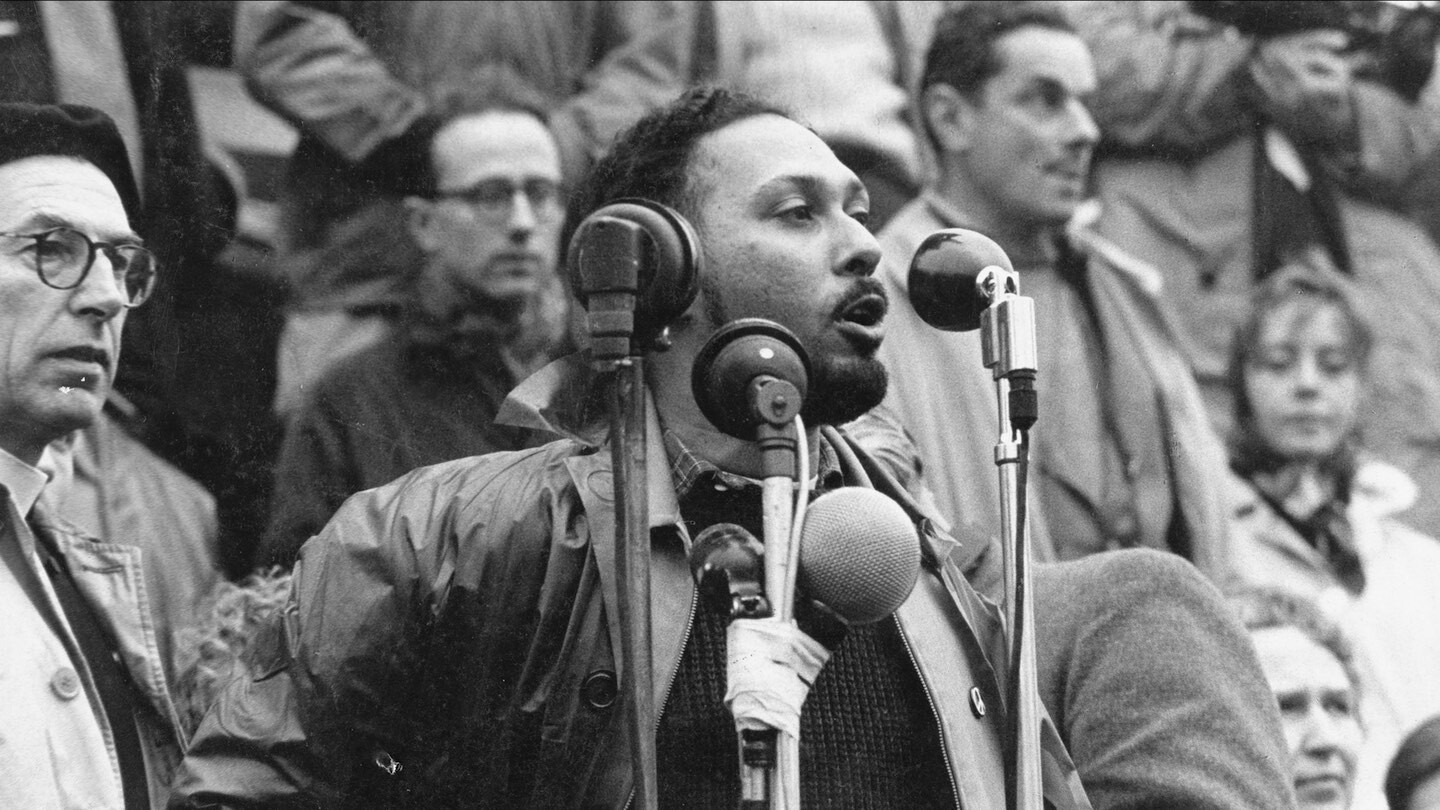

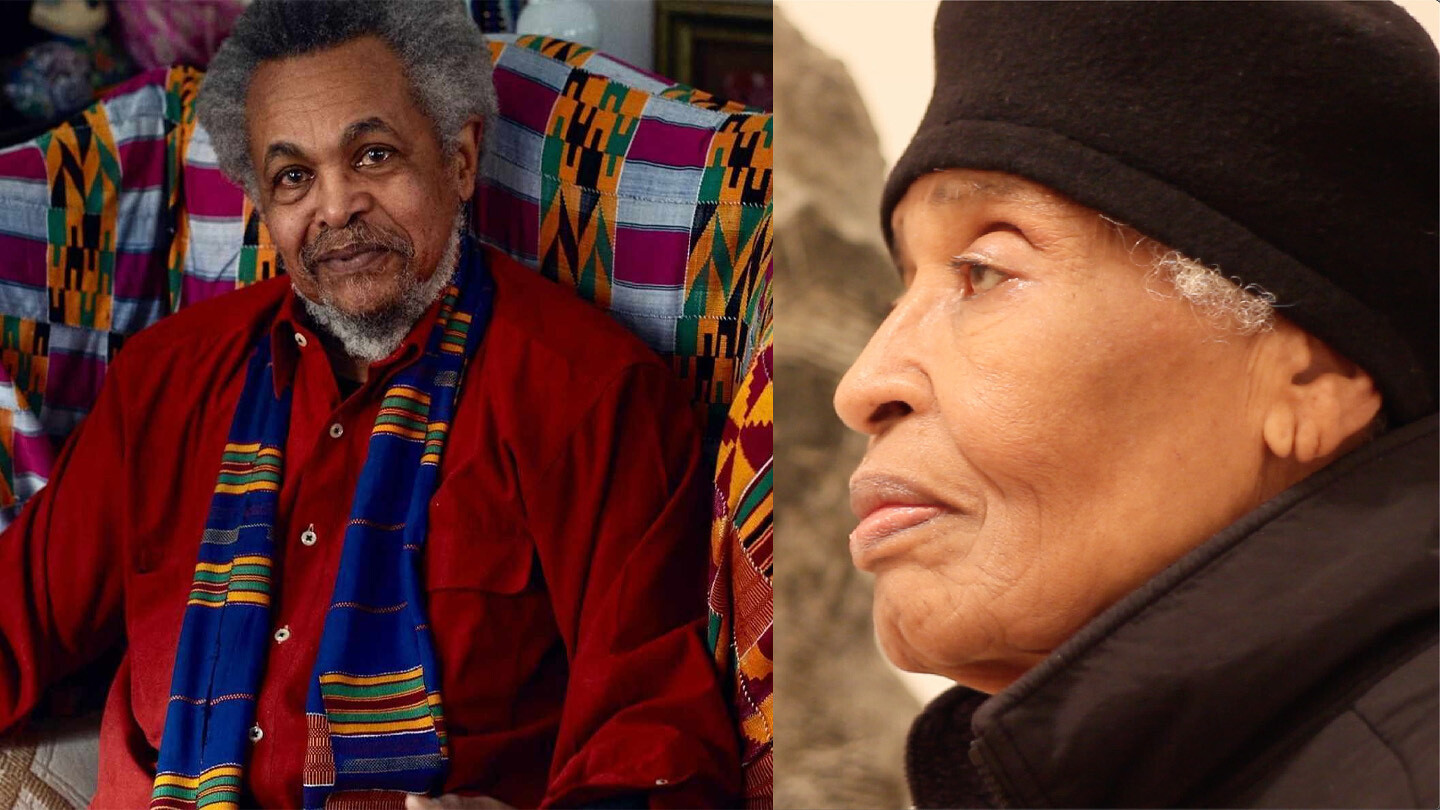

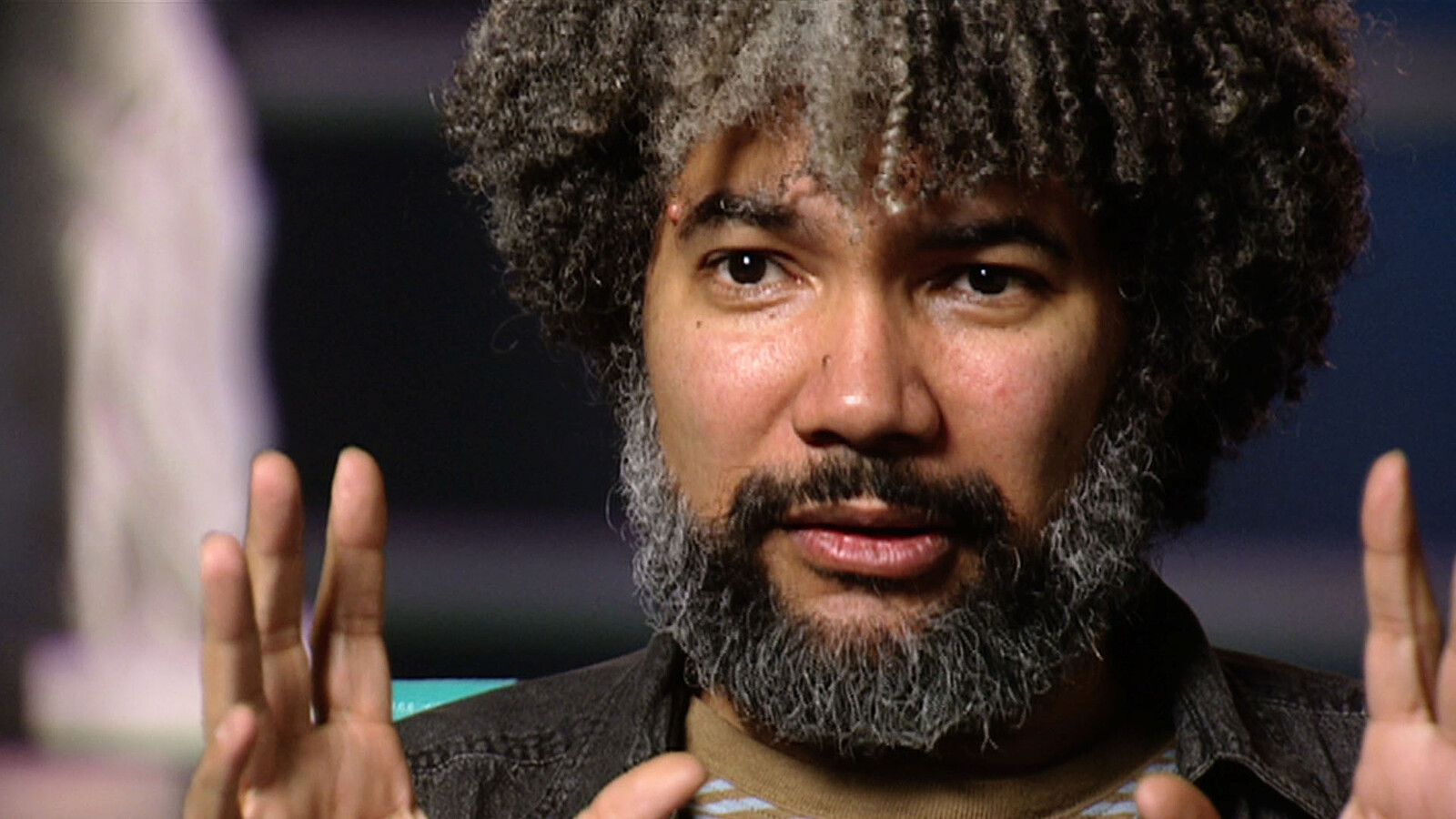

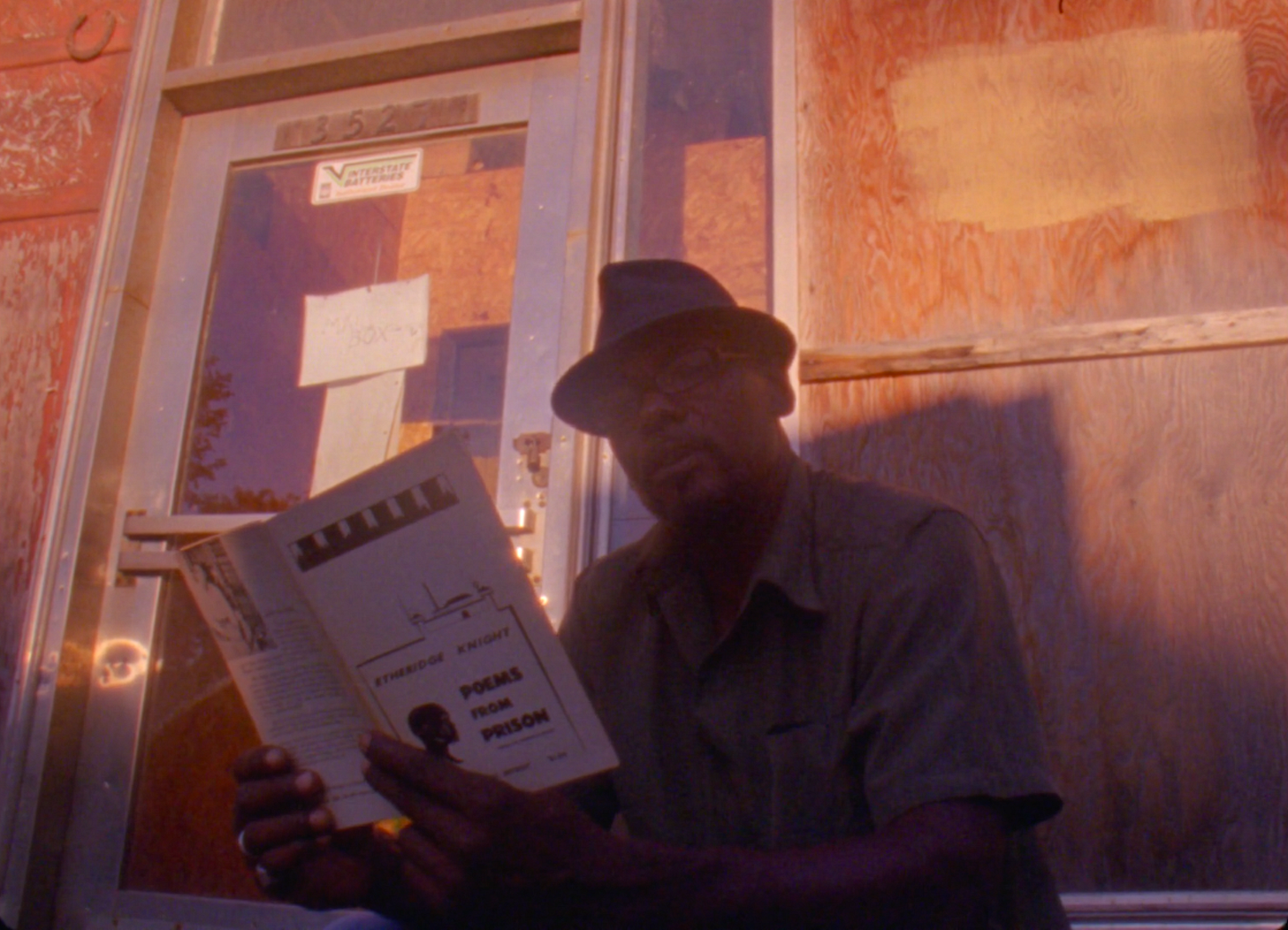

John Akomfrah, The Stuart Hall Project

By invoking eighteenth- and nineteenth-century history—such as the Haitian Revolution and the Chimurenga in Southern Africa—and transnational trajectories not only of artists and writers but of exhibitions, the panel on “Citational Practices” moved away from a tendency towards the nationalization of discourse. This movement is one of the gestures that makes solidarity and reproducibility possible.

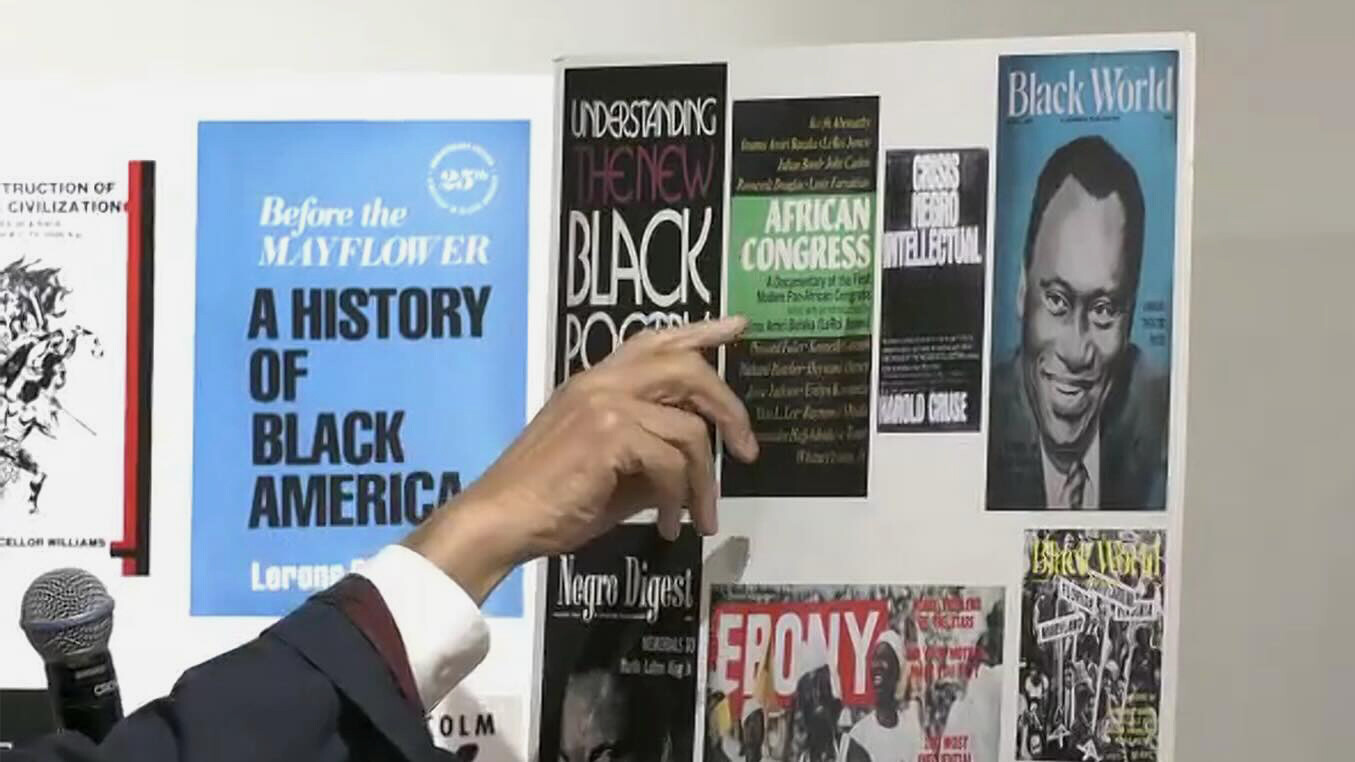

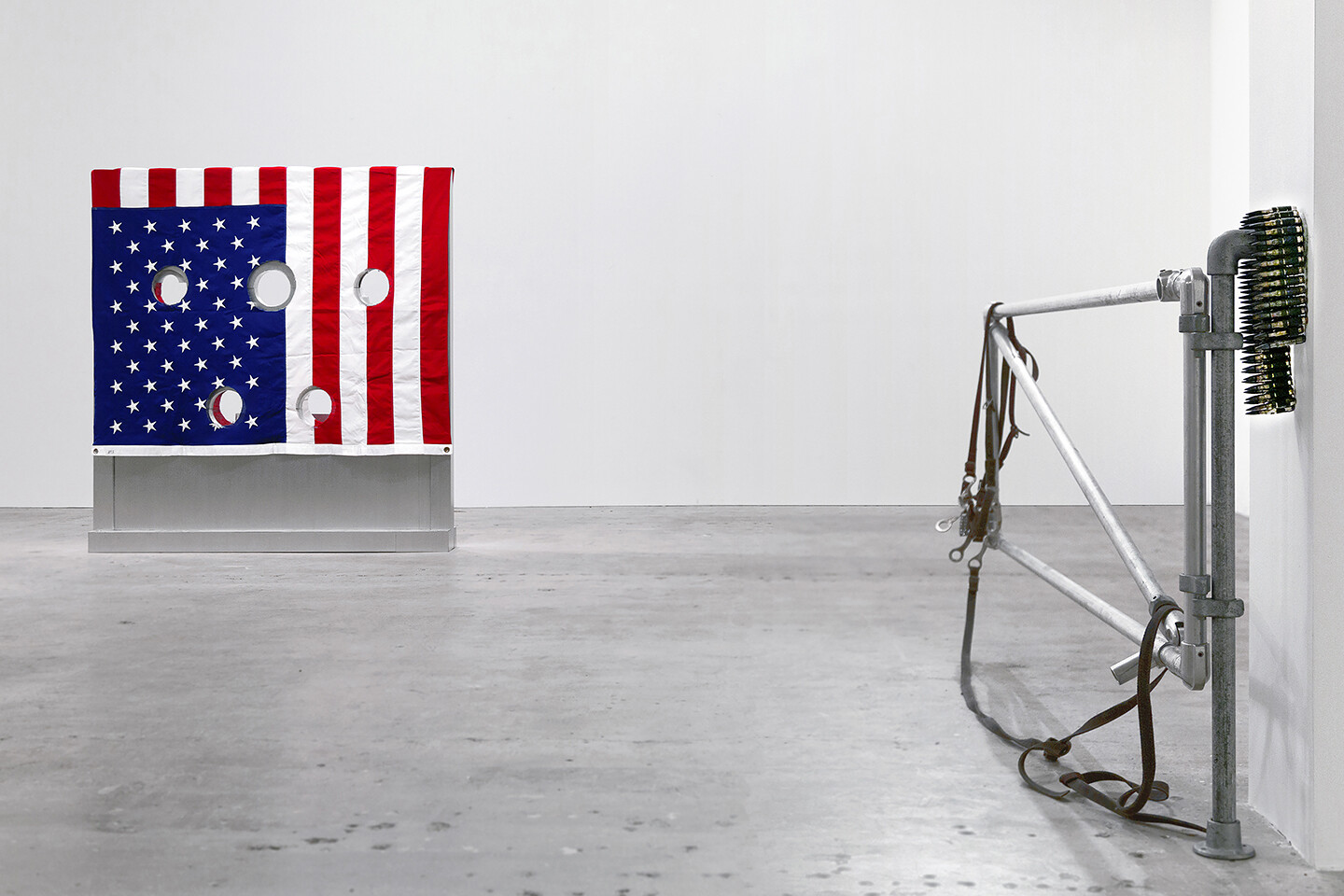

Long before Nazi violence came to be conceived as beyond comparison, Black radical thinkers sought to expand the historical and political imagination of an anti-fascist left by detailing how what could be perceived from a European or white vantage point as a radically new form of ideology and violence was in effect continuous with the history of (settler-)colonial dispossession and racial slavery.

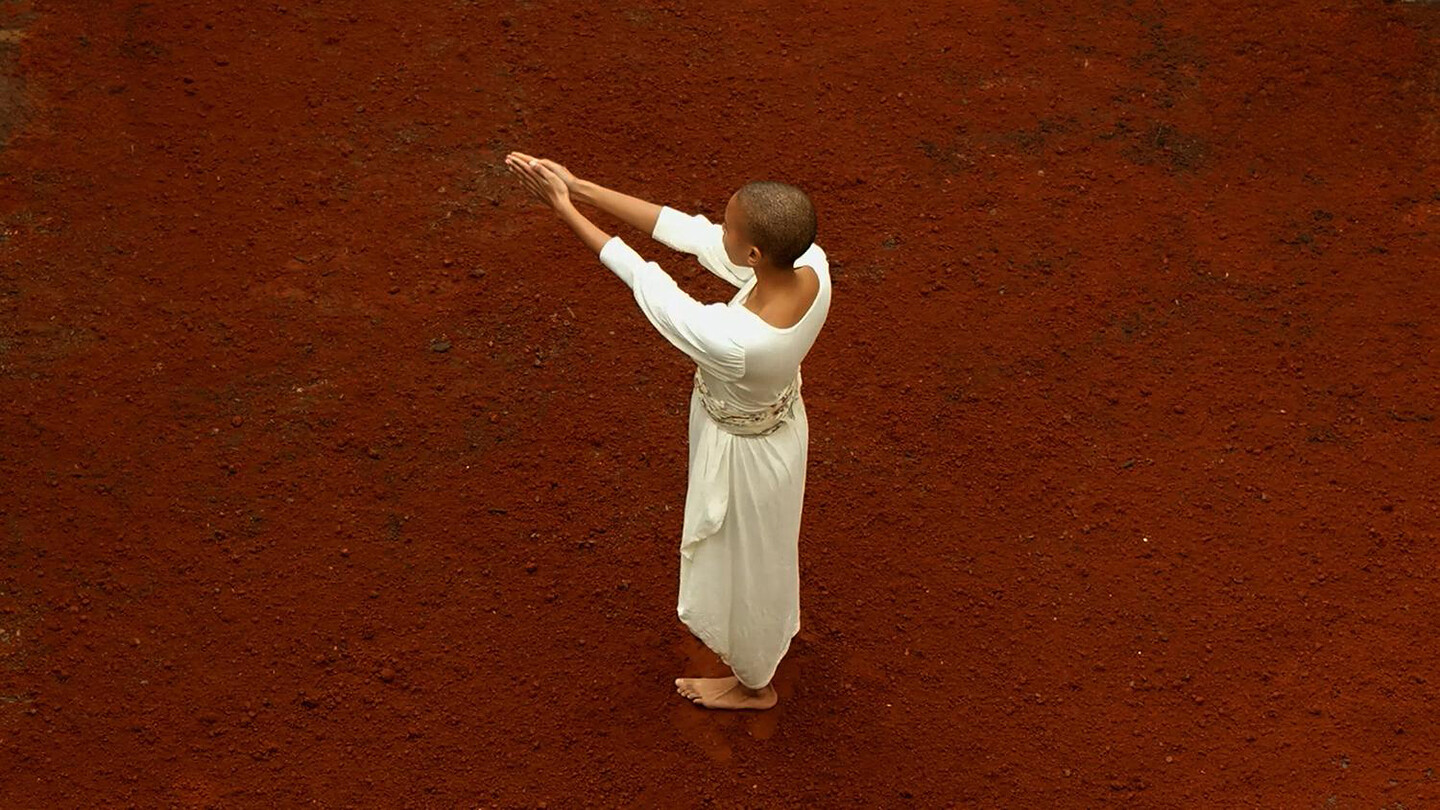

Social scientists regularly work in study groups and research groups. They develop theses and propositions and experiments based on group work. Whereas we in the humanities are trained not to do this. We are trained to write in a single voice. It was very interesting to me last semester teaching a class with practice-of-art students called “Radical Composition.” From the very beginning, students were divided into groups of three, and each group had to create a radical composition in response to a series of assigned visual, sonic, and written texts. They were musicians and visual artists and movement artists and art historians and African American Studies students. And they all said the same thing: we’ve never been taught how to work in a group. We have our single-person senior shows. We produce our own body of work. Sometimes we help each other out, but it’s not multiauthored. We don’t all take credit.

I look at music as a sculptor might. I get the materials and just have this lump of sounds sitting there, and then I chisel away at it until it starts to sound like something. I say it’s techno, but I’m not sure that it’s actually techno. What is techno? That’s a question. But maybe what my music does is define what it could be, or what else it could be. Genres can be limiting.

What do they know of techno, that only techno knows? This is a good question to ponder, I suggest, even though or perhaps because it has no answer. The very act of asking it, without the capacity of a satisfactory answer, delivers us to that paradoxical space of affirmative negation. This is the space, I think, that is in turn necessary for “unlocking the groove” wherein the difference that techno is and still might yet be lies.

Of course, “Litcoin” crashes and everyone in South Side is left with nothing. Odom, the amateur astronomer, is depressed by the lost opportunity to purchase a powerful telescope. A rare comet is making its way around the solar system and he wants to see it. But he is broke again. At this point, the show makes a leap into the cosmic. All along, and all around the South Side, they have been surrounded by the cosmic. It can only be accessed by a form of wonder (thaumazein) that Hannah Arendt described in her book The Promise of Politics.

Within the shared sociohistorical field of black cultural practice, within the neglected realms of the studium, homogeneity and heterogeneity are instead bound up in shifting but complementary relation. In this model, repetition and differentiation are not antagonistically opposed. Difference is not exclusionary, and similitude is not unprepossessing.

The genocide of relation can never be traced back, quite. Relation cannot be propertied. What is lost cannot be parsed.

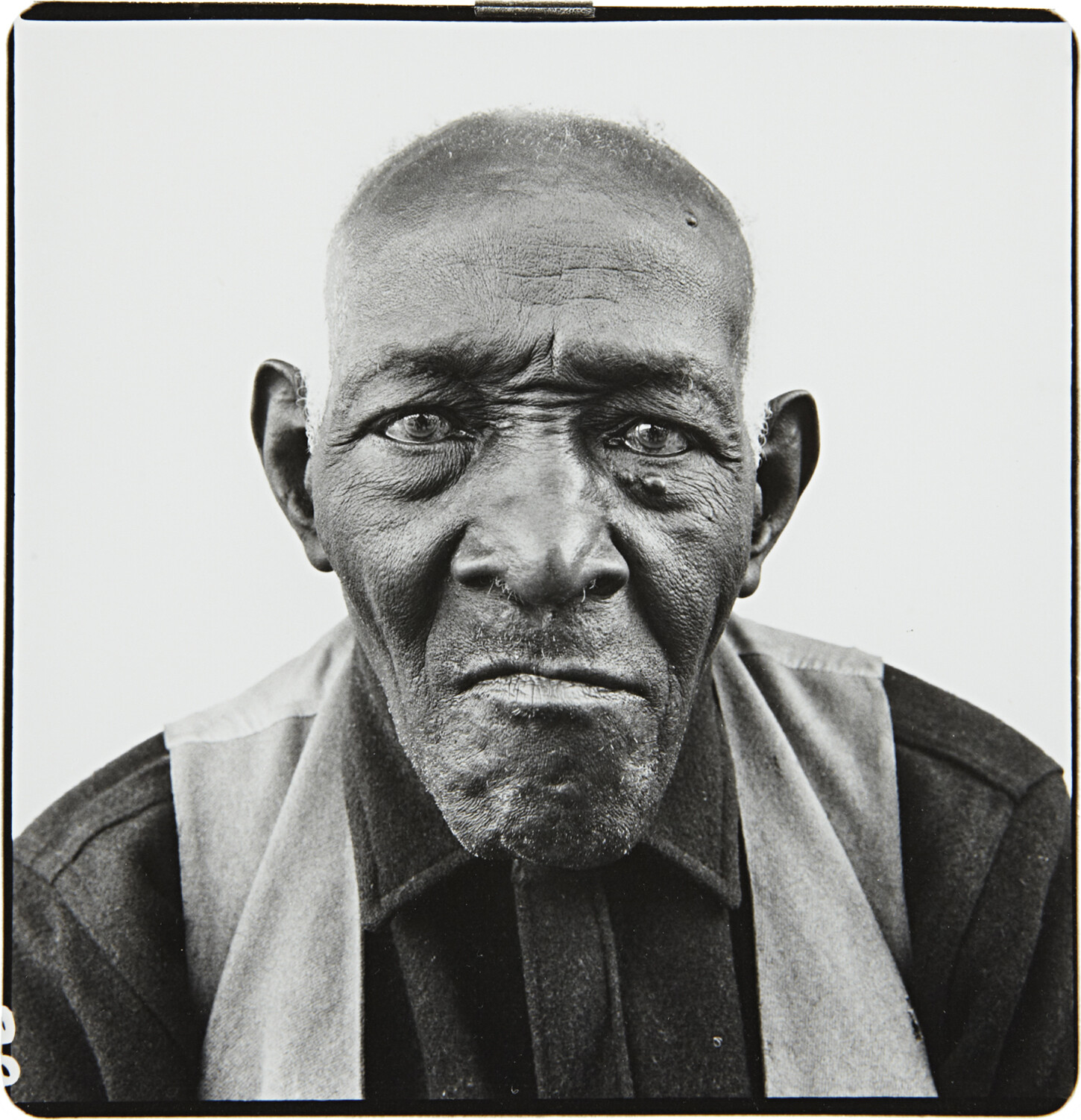

In contemplating Camera Lucida now, in the wake of the fortieth anniversary of its publication, I am moved to ask: How could a book so intensely bound up with photography and loss show so little generosity, and why, today, should we heed its call? Beyond this, what might insights from black studies bring to bear on a book so indebted to the identification and rejection of difference in the expropriative formulation of Barthes’s inner self?