Amol K Patil’s white plasterboard architectural structures, referring to vernacular architecture in Mumbai, sit uneasily in the vast, postindustrial main hall of Röda Sten Konsthall. A raised floor with a roof the size of a small room abuts a low and irregularly shaped platform, each supporting an array of sculptures. They are intended as homage to the chawl, a distinctive form that evolved from housing for mill workers under British colonial rule in the late nineteenth century.

Initially designed for single occupancy with common spaces and courtyards, the chawls soon exceeded their intended function as isolated residences within the mill compound. Workers arriving in the city with families modified them, so that social structures from Rajasthan, Gujarat, the Konkan coast, and elsewhere became entangled with those of Mumbai. Though they had few amenities, the chawls provided a social safety net that Prasad Shetty, co-founder and professor at School of Environment and Architecture in Mumbai, describes as “an architecture of care.”1 This sociality is absent from Patil’s clean silhouetted representation. I am struck by the discord between what is referenced and what is given to be experienced.

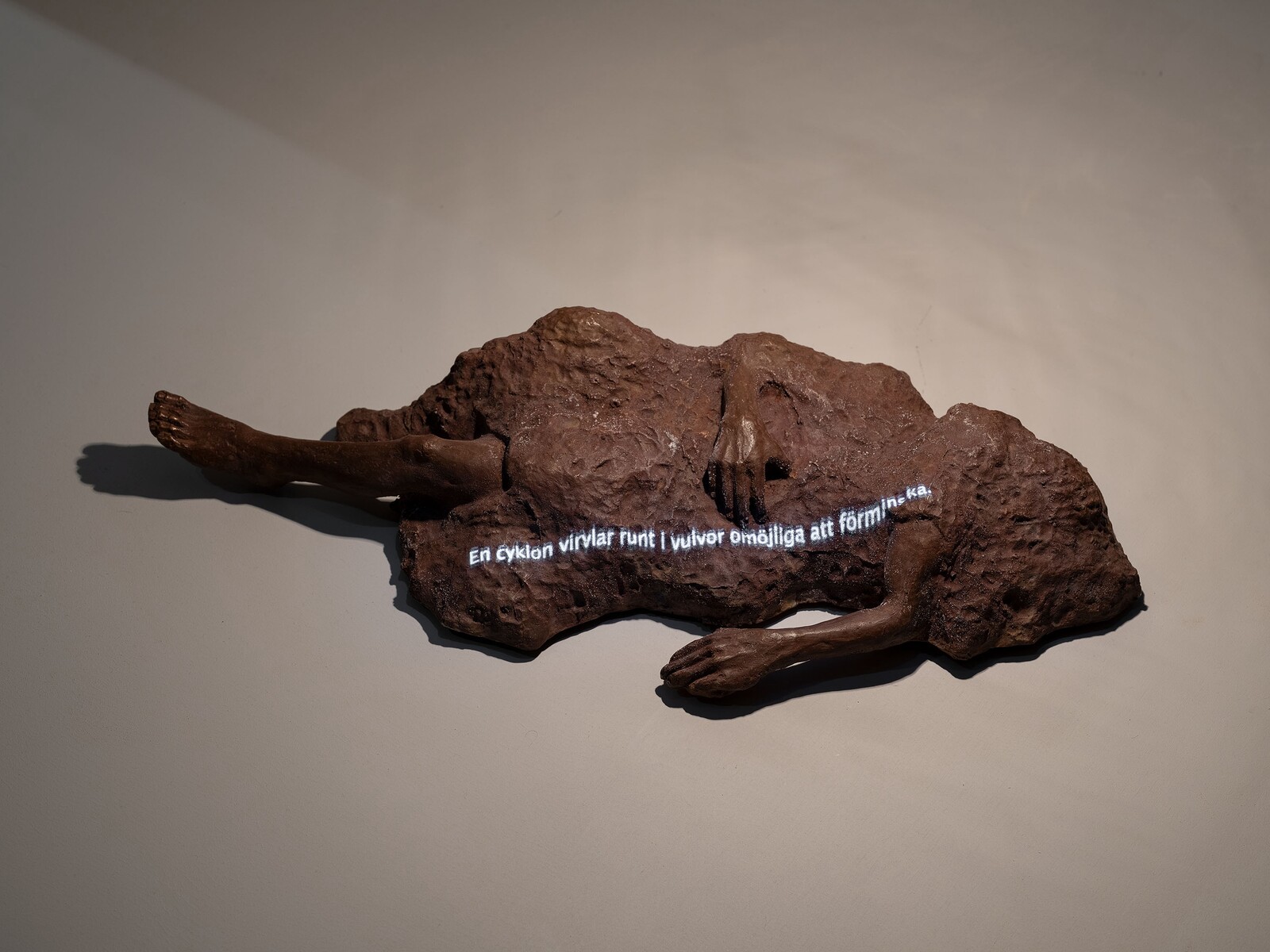

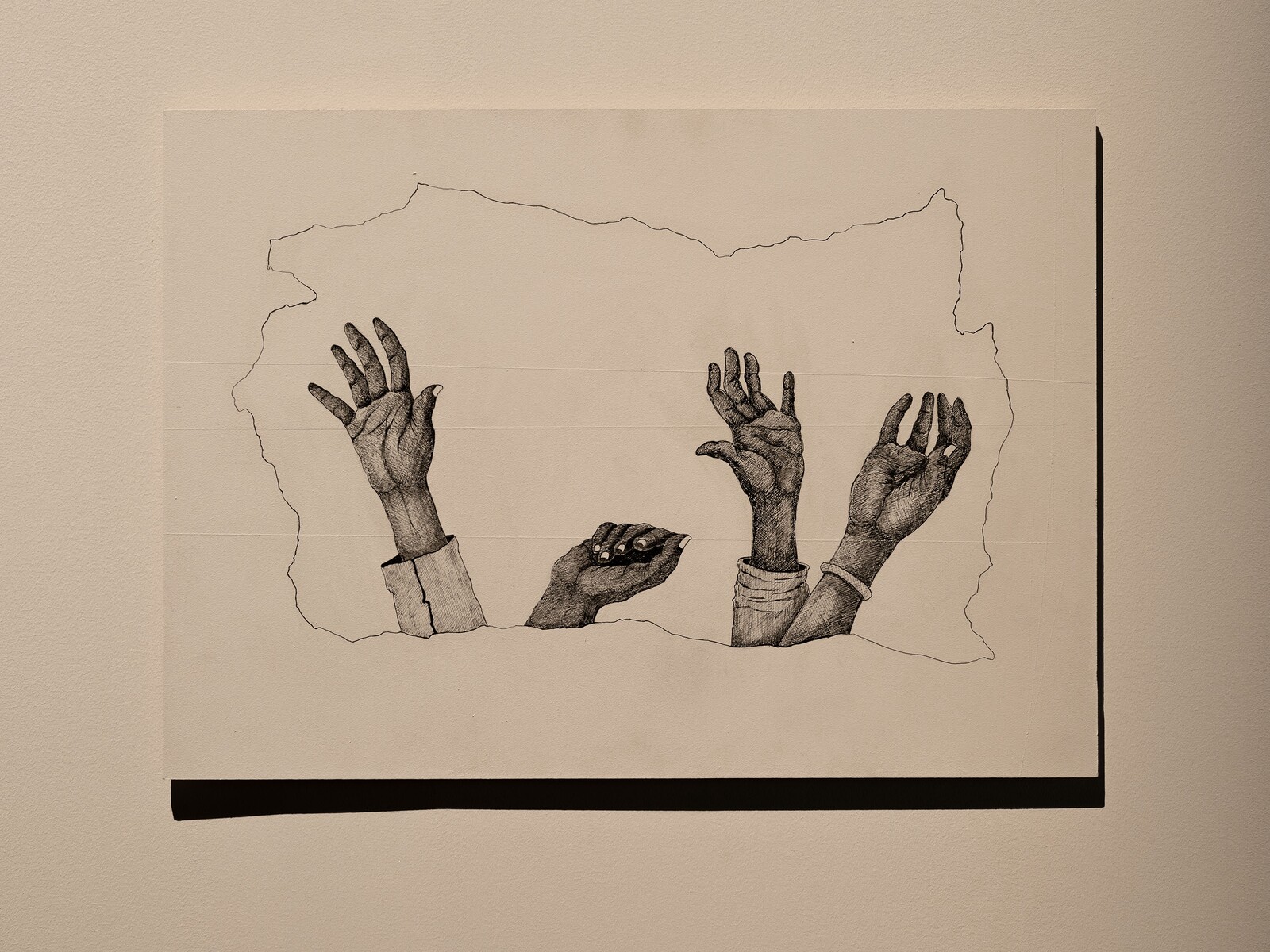

Instead, the affective impact of the work is of diffuse, nostalgic mourning. An audio cassette emerges halfway from a mass of unpolished bronze in a sculpture the size of a small bundle. Hands and feet are scattered across the walls, also cast in bronze, tethered to long metal rods shaped to evoke the rest of the body. Pen-and-ink drawings of torsos, arms, a belt are framed by shapes reminiscent of territorial borders. A prone corporeal shape is covered by a large mass, perhaps a blanket or a pile of earth. Poetry is projected onto it from above as a subtitle line of white script against the muddy color of the unfinished metal.

These works could have been taken from the archeological sites in China Miéville’s political science-fiction novel The City and The City (2009), or from Marcel Broodthaers’s Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles (1968). Their ambition, stated in the exhibition guide, is to depict “the ambivalence of life in chawls,” and to reflect on “how bodies and silent conversations have become embedded in the housing that shapes the urban lives of modern cities.” They act on me instead as isolated objects plumbed from long-neglected history.

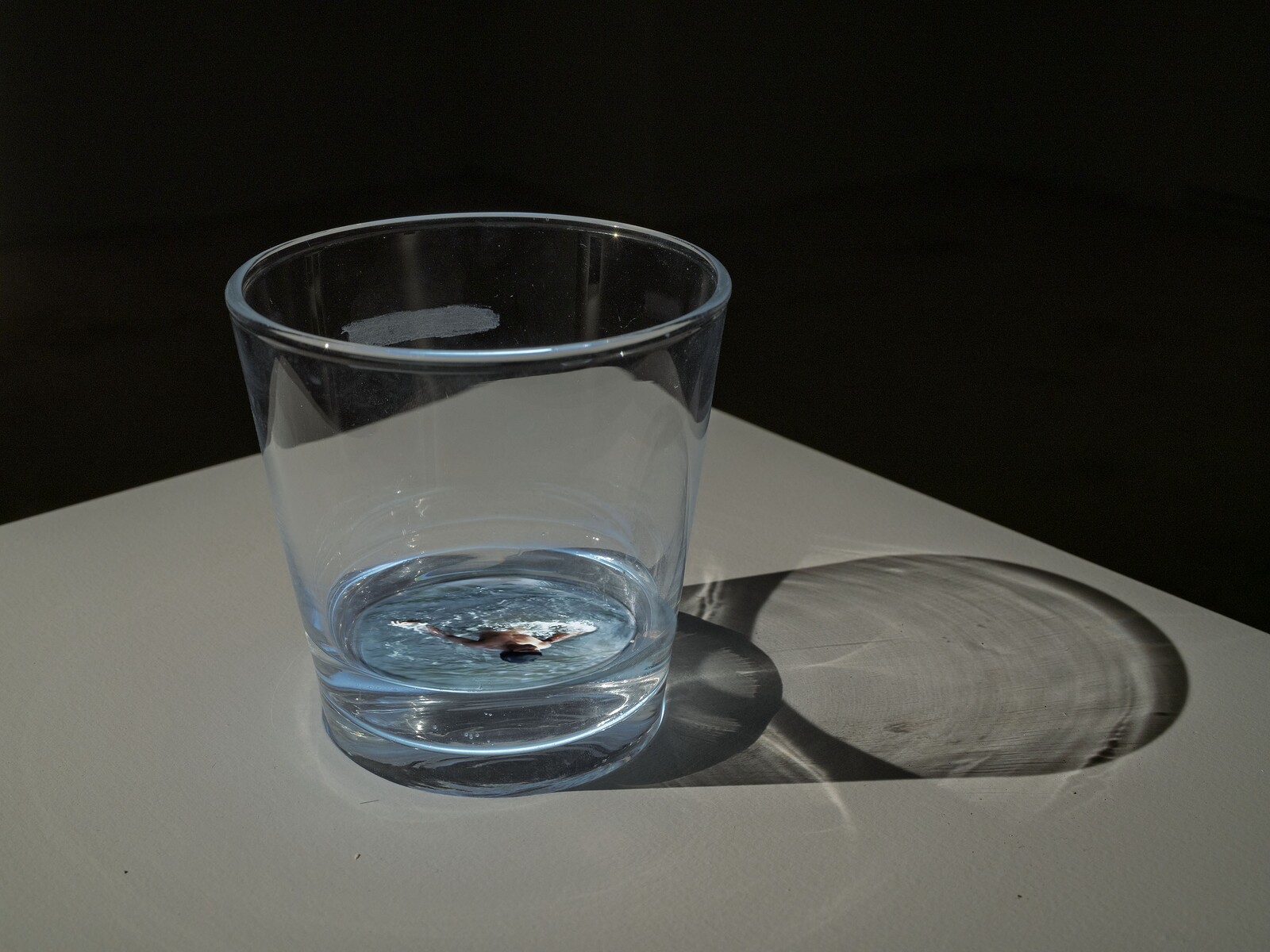

This dissonance evaporates on the exhibition’s upper floors, which show past work. Let’s Clean Our Hands (2022), a holographic video of a man washing himself in a river, is projected into a small drinking glass of the kind typically offered to upper-class guests upon arrival. The focused beam of light produces a tantalizing luminosity in the darkened room. The image evokes the delicious intimacy of cool, moving water against naked skin in the sparkling sun. Access to water has been a major axis of the Dalit political movement, as members of the lower caste are often denied not only water to bathe in or for household chores, but clean drinking water. The political register is implicit in the pleasure the piece evokes in the viewer. The video elicits the desire for water, and its form is a vessel for hospitality that invites the fantasy of desire’s fulfilment. There is no slippage, here, between political reference and embodied experience.

The surrounding walls are dappled with spotlights, each illuminating a painting that is black save for some detail: a fire burst in one, a matrix of flashlight beams in another, the silhouette of a man’s head backlit by a faint greenish LED lamp in a third. “In search of light,” the exhibition text reads, “the working class has traveled vast miles to reach the cities, but as they approach, they face constant struggle and the darkness of endless roads.” Patil does not render the degree of migrants’ exposure as monolithic, but instead offers the viewer hopefulness at the smallest scale, that of the battery-powered flashlight against the immensity of the night.

That hope is given to be seen in vernacular terms, using modest materials, is less unusual than that it be rendered without any tangible image of culmination. No illuminated city or joyous reunion around a nourishing meal awaits the viewer at the conclusion of the exhibition. There is the viscous night, there are flashlights, there is the endless road, and there are other people on the road as well. Implicit is the idea that the struggle is the vector for solidarity, and that it alone bears representing.

Ronojoy Mazumdar, “How ‘Chawl’ Tenements Helped Mumbai Become a Megacity,” Bloomberg (November 1, 2023), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2023-11-01/mumbai-chawl-tenements-helped-build-the-megacity-but-they-are-under-threat.