In a recent review of Mark Leckey’s work, Laura McLean-Ferris wrote of the artist’s remarkable ability to conjure the “experience of being overcome” that is typically associated with religious experience. Her article—and its citation of Peter Schjeldahl’s comparably revelatory encounter with Piero della Francesca—prompted the question of why this type of experience should be so exceptional in the life of an art critic. Shouldn’t those of us who spend our days going to exhibitions regularly be overwhelmed? Shouldn’t every work of art at least aspire to these effects? Have we become jaded, or is something else going on?

Throughout his fifty-year career, the London-based French artist continued playfully reflecting on the changing relationship of the contemporary art field towards its peripheries. These once-forbidden pleasures included pop culture and the counterculture, domesticity and the “House Beautiful,” androgyny, ornamentation, dandyism, “minor” artistic practices (figures like Jean Cocteau, a member of what he termed the “B list” of art history), male vulnerability and autobiographic exposure, and “applied” arts such as wallpaper, textile, and furniture design.

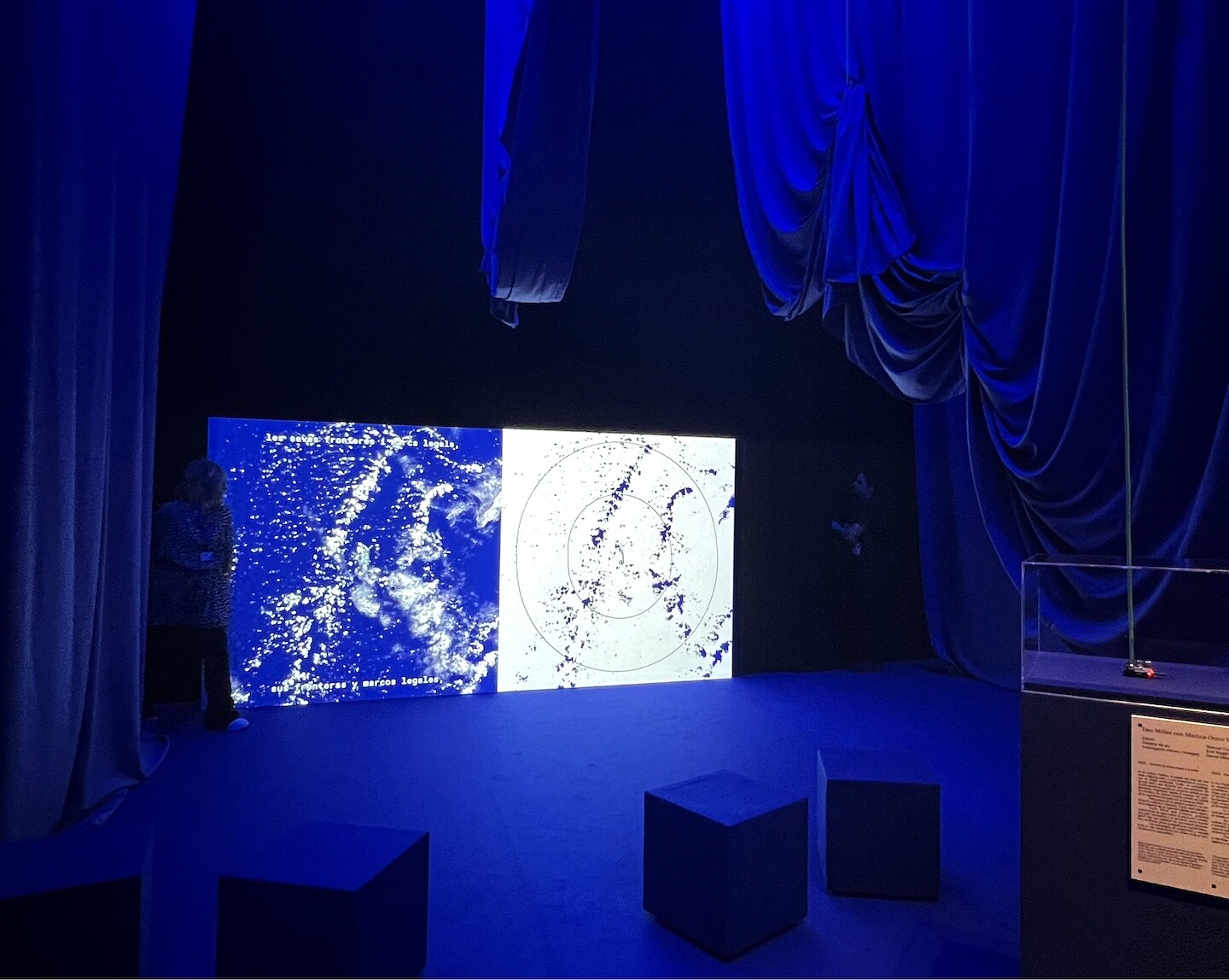

Fragmentos Espacio de Arte y Memoria follows the example of local leaders, including former Bogotá mayor and social practice artist Antanas Mockus, in its aim: to fuse art and policy and bring publics together to process the trauma of decades of war. Curator Carolina Cerón gathers pieces by five Colombian artists—Mónica Restrepo, Ana María Montenegro, María Leguizamo, David Medina, and María Isabel Arango—whose work “bridges past and present.” The show poses the question of what to do with sociopolitical and cultural memory of years of armed conflict and an imperfect peace process, set against the resolutely violent backdrop of Doris Salcedo’s monument.

If the modern city provides scant refuge for the politically conscious, immigrants, and the socially precarious (including communities engaged in sex work, cruising, or drug taking), then graffiti here retains its image as its persistent mise-en-scène. The poet Anne Carson described graffiti as “often ugly and usually, on some level, activist,” yet this exhibition largely eschews any overt political messaging, instead repositioning graffiti as an unconscious manifestation of a lifeworld largely held by force under the surface of a city by force, painted emanations momentarily registered upon its surfaces only to be latterly scrubbed off by sunrise.

Eight years after the film introduced the artists to an international audience—and confirmed them as icons to a younger queer community in Italy—their lives continue as before. Their celebrity and acknowledged cultural significance has not been translated into exhibitions or documentation of their performances and artworks in any tangible way beyond Passerini’s film. Like many artists who do not fit neatly within the taxonomies of commodifiable art, professional social networks, or brandable trends, their work has not been supported by grants, institutional acquisition, or commercial representation. As the state interferes in, and manipulates, cultural institutions in Italy and elsewhere, there is an increasing value in attending to cultural production, critical discourse and ways of living that fall outside of those networks.

Amol K Patil’s white plasterboard architectural structures, referring to vernacular architecture in Mumbai, sit uneasily in the vast, postindustrial main hall of Röda Sten Konsthall. A raised floor with a roof the size of a small room abuts a low and irregularly shaped platform, each supporting an array of sculptures. They are intended as homage to the chawl, a distinctive form that evolved from housing for mill workers under British colonial rule in the late nineteenth century. Initially designed for single occupancy with common spaces and courtyards, the chawls soon exceeded their intended function as isolated residences within the mill compound.

Leiden University’s announcement that it will “phase out” the funding for its Academy of Creative and Performing Arts (ACPA) is not just a bureaucratic decision; it is a profound and short-sighted blow to the intellectual, cultural, and artistic fabric of the Netherlands.