The Editors

George MacBeth

Chris McCormack

Eloise Fornieles

Natasha Marie Llorens

Critical writing from the expanded field of contemporary art.

Editor-in-chief

Ben Eastham

Editors

Patrick Langley

Francesca Wade

Assistant Editor

Novuyo Moyo

Contact

criticism@e-flux.com

See Credits

Close Credits

Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

May 2, 2025 – Editorial

By the book

The Editors

In a recent review of Mark Leckey’s work, Laura McLean-Ferris wrote of the artist’s remarkable ability to conjure the “experience of being overcome” that is typically associated with religious experience. Her article—and its citation of Peter Schjeldahl’s comparably revelatory encounter with Piero della Francesca—prompted the question of why this type of experience should be so exceptional in the life of an art critic. Shouldn’t those of us who spend our days going to exhibitions regularly be overwhelmed? Shouldn’t every work of art at least aspire to these effects? Have we become jaded, or is something else going on?

The challenge and reward of writing about art is in trying to articulate experiences that resist expression in language. Yet noone working in the field can have failed recently to notice the increased pressure on artists to move in the opposite direction: to ensure from the beginning that their work is so easily legible as to foreclose any possibility of its misinterpretation. In which case, the apparent scarcity of transformative experiences might be neither the symptom of a general disillusion nor proof that the present generation of artists is unable to produce them. It might instead be attributed to an institutionalized anxiety …

April 30, 2025 – Book Review

Marc Camille Chaimowicz’s Writings and Interviews

George MacBeth

Stuart Morgan wrote of Marc Camille Chaimowicz that through his work we can come to “Unlearn ‘art’. Unlearn ‘artwork’. Unlearn ‘closure.’ Unlearn ‘public’ and ‘private’. Finally, unlearn ‘man’.” Throughout his fifty-year career, the London-based French artist continued playfully reflecting on the changing relationship of the contemporary art field towards its peripheries. These once-forbidden pleasures included pop culture and the counterculture (particularly pop music), domesticity and the “House Beautiful,” androgyny, ornamentation, dandyism, “minor” artistic practices (figures like Jean Cocteau, a member of what he termed the “B list” of art history), male vulnerability and autobiographic exposure, and “applied” arts such as wallpaper, textile, and furniture design.

Informed by second wave feminism and the gay rights movement, his pioneering ’70s–’80s works, such as the scatter installation Celebration? Real Life (1972) or the mixed-media performance Partial Eclipse (1980), exhibit an at-once generous and elliptical sensibility that refuses to play it straight. Like curtains or folding screens, both of which he began exhibiting in the 1980s, his work feels hospitable while also working to keep certain things occluded from view. Championed by a younger cohort of enthusiastic critics, curators, and gallerists in the 2000s, a number of high-profile shows in the latter stages …

April 29, 2025 – Review

“La madre, las palabras con los nombres, un sorbo y cuatro rayos”

Kim Córdova

How do we move beyond histories that no longer fully represent us? The 2016 peace agreement with the FARC, which brought to an end roughly fifty years of war between the Colombian government and left-wing militia groups, stipulated three monuments to be built from the militias’ surrendered weapons and munitions. Doris Salcedo’s commemorative monument in Bogotá—a commission from the Colombian Ministry of Culture—inverted and expanded the idea of heroism usually accorded to monuments. She designed a cast iron floor made from thirty-seven tons of melted-down weapons that were cast in molds hammered into shape by women victims of sexual violence by guerrillas during the conflict.

This anti-monument was installed in a new cultural center—Fragmentos Espacio de Arte y Memoria—in the retrofitted ruins of a house from 1565 in Bogotá’s La Candelaria neighborhood. The center follows the example of local leaders, including former Bogotá mayor and social practice artist Antanas Mockus, in its aim: to fuse art and policy and bring publics together to process the trauma of decades of war. At Fragmentos, curator Carolina Cerón gathers pieces by five Colombian artists—Mónica Restrepo, Ana María Montenegro, María Leguizamo, David Medina, and María Isabel Arango—whose work “bridges past and present.” The …

April 28, 2025 – Review

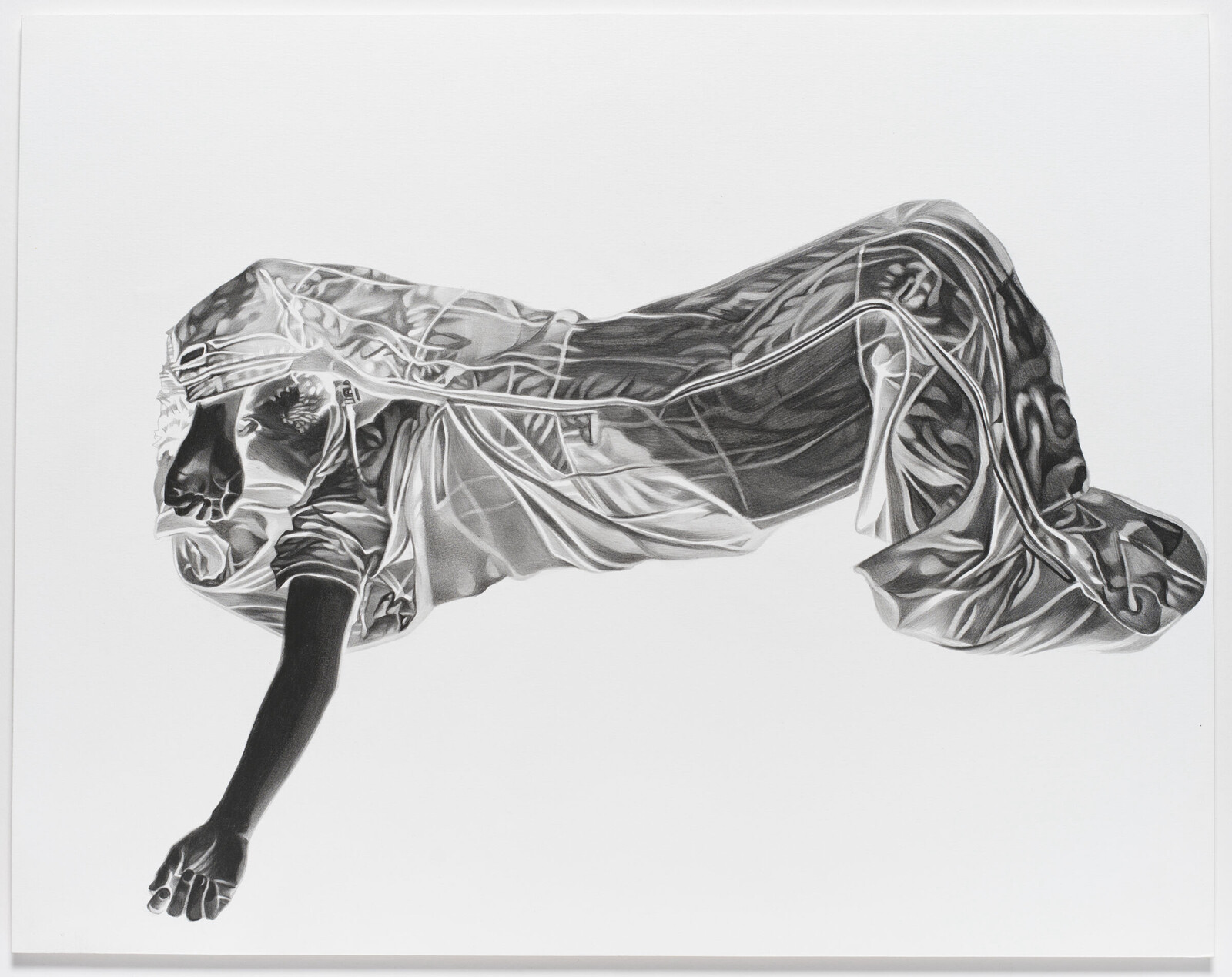

“Graffiti”

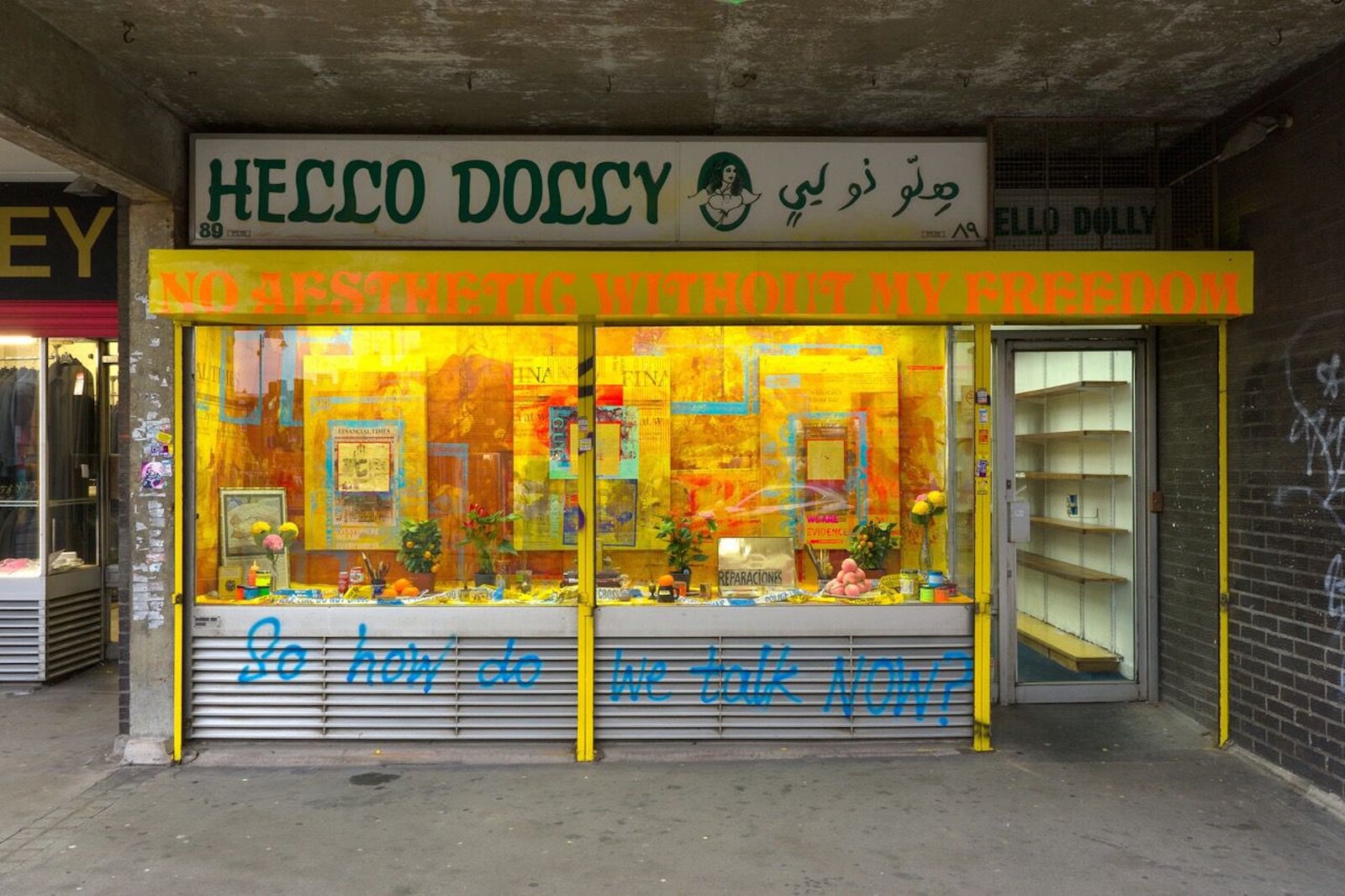

Chris McCormack

The expansive survey exhibition “Graffiti,” curated by Leonie Radine and artist Ned Vena, begins in 1951—the year spray paint was patented in the United States. This seemingly banal technical footnote functions as a clear material marker: the pressurized paint can prefigured a wider transformation in postwar conceptual art practices and beyond. Central to this curatorial narrative is the short period when spray paint was embraced by studio-based artists in the 1950s and ’60s, seemingly drawn to its vaporous, cool finish. This was upended when spray paint started to appear on streets, subways, and bus shelters across New York City, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia through the 1960s: a period that continues to shape conceptions of “graffiti,” largely imagined by marginalized African American and Latinx youth—the exhibition overall tilts towards this US perspective.

If the modern city provides scant refuge for the politically conscious, immigrants, and the socially precarious (including communities engaged in sex work, cruising, or drug taking), then graffiti here retains its image as its persistent mise-en-scène. The poet Anne Carson described graffiti as “often ugly and usually, on some level, activist,” yet this exhibition largely eschews any overt political messaging, instead repositioning graffiti as an unconscious manifestation of a …

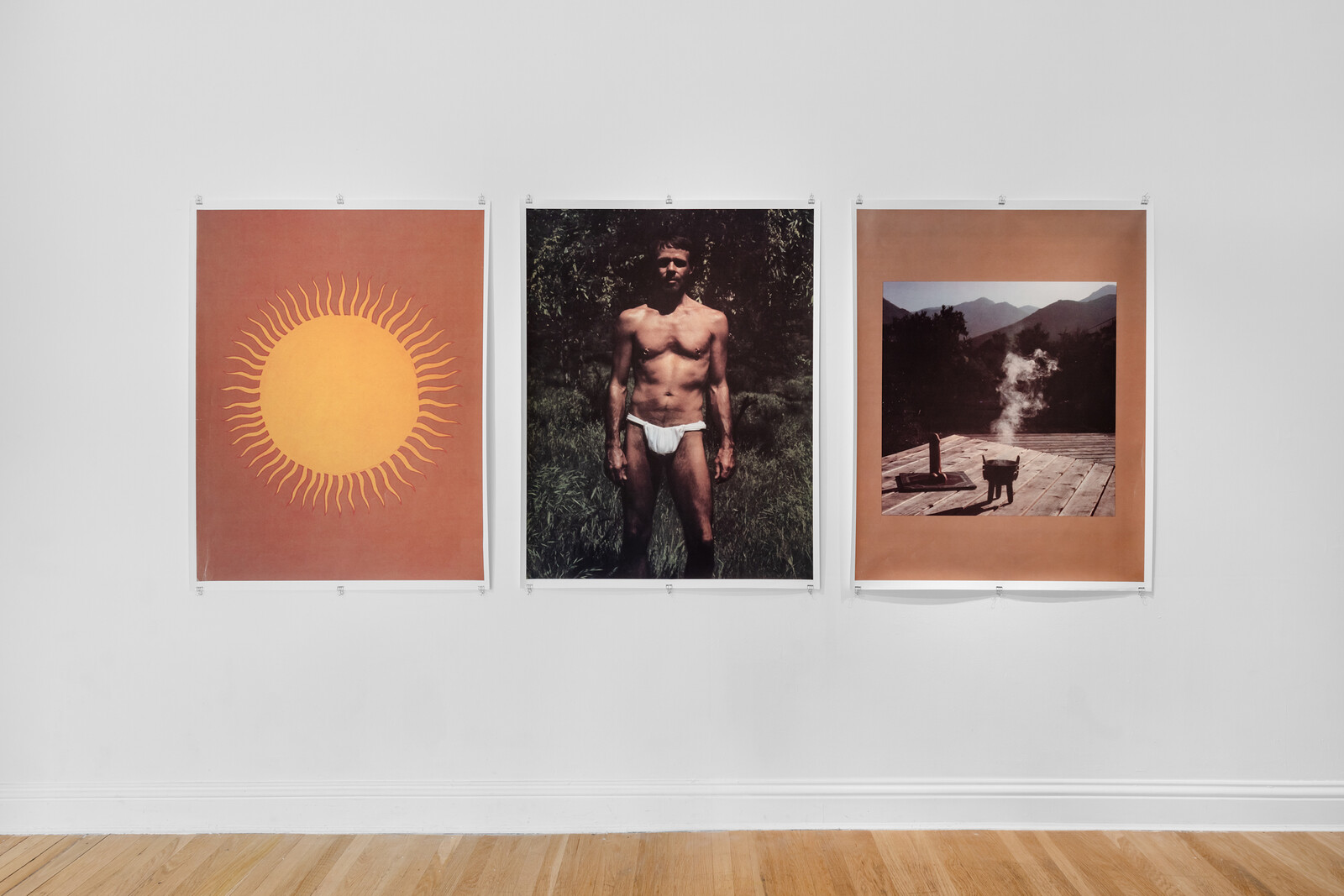

April 25, 2025 – Feature

On Il Principe di Ostia Bronx

Eloise Fornieles

The experimental documentary Il Principe di Ostia Bronx (2017) tells the story of Dario Galetti Magnani and his life partner and collaborator Maury Fonte, better known on the beaches of Ostia as “Il Principe” and “La Contessa.” Directed by Raffaele Passerini, the film shows the duo in a variety of costumes performing improvised protests and scraps of scripts to sunbathing day-trippers from nearby Rome, all the while blasting music on a stereo. Rejected by academia and mainstream theater in their twenties, the pair have spent decades recording each other delivering melodramatic and comic dialogues on the beach. As a temporary third member of the creative-unit-cum-chosen-family, Passerini turns our attention to queer ways of living, worldmaking, tender bickering, homemade films, and homemade pizza: which is to say, to art and to love.

Eight years after the film introduced the artists to an international audience—and confirmed them as icons to a younger queer community in Italy—their lives continue as before. Their celebrity and acknowledged cultural significance has not been translated into exhibitions or documentation of their performances and artworks in any tangible way beyond Passerini’s film. Like many artists who do not fit neatly within the taxonomies of commodifiable art, …

April 24, 2025 – Review

Amol K Patil’s “The Shadow of Lustre”

Natasha Marie Llorens

Amol K Patil’s white plasterboard architectural structures, referring to vernacular architecture in Mumbai, sit uneasily in the vast, postindustrial main hall of Röda Sten Konsthall. A raised floor with a roof the size of a small room abuts a low and irregularly shaped platform, each supporting an array of sculptures. They are intended as homage to the chawl, a distinctive form that evolved from housing for mill workers under British colonial rule in the late nineteenth century.

Initially designed for single occupancy with common spaces and courtyards, the chawls soon exceeded their intended function as isolated residences within the mill compound. Workers arriving in the city with families modified them, so that social structures from Rajasthan, Gujarat, the Konkan coast, and elsewhere became entangled with those of Mumbai. Though they had few amenities, the chawls provided a social safety net that Prasad Shetty, co-founder and professor at School of Environment and Architecture in Mumbai, describes as “an architecture of care.” This sociality is absent from Patil’s clean silhouetted representation. I am struck by the discord between what is referenced and what is given to be experienced.

Instead, the affective impact of the work is of diffuse, nostalgic mourning. An …

April 23, 2025 – Review

Ed Atkins

Michael Kurtz

Ed Atkins’s survey show at Tate Britain was initially going to be called “Loss” but opened with only the artist’s name above the door. Perhaps “Loss” didn’t scream summer blockbuster? Regardless, the decision to scrap this working title, mentioned without explanation in the catalog, seems significant. Gathering around sixty works from the last fifteen years, the exhibition charts a turn in Atkins’s practice from experimentation with digital technology as a metaphor for loss—alienation, emptiness, death—toward a more expansive engagement with art as a tool for personal expression, social connection, even redemption.

In the early 2010s Atkins established an international reputation with CGI films of lonely, weather-beaten men delivering strange soliloquies voiced by the artist. On display at Tate, Hisser (2015) presents one such figure wandering round his bedroom, his face covered in computer-generated wrinkles and purple sores. He masturbates in the corner before lying down and singing “didn’t know that life was so sad I cry.” The film is full of formal quirks: at one point the whole room slides down the screen to reveal a series of identical spaces like frames in a reel. Suddenly the specific details of this private interior, of intimate experience, appear formulaic and endlessly …

April 21, 2025 – Review

Joëlle Tuerlinckx’s “El caso de l(a casa) museo(a)”

Patrick Langley

The first work the viewer encounters is a large cardboard maquette of the show they have just stepped into, complete with scale models of artworks, including one of the maquette itself, and crude cardboard miniatures of museumgoers like them. Maqueta ‘El caso de l(a casa) museo(a)’ (2024) signals from the outset that Belgian artist Joëlle Tuerlinckx intends to subvert not only viewers’ expectations, but the apparatus of exhibition-making.

Across the museum’s six subterranean galleries, lights turn off and on at random-seeming intervals. Holes are cut into the walls. A room is rendered inaccessible by a sheet of Plexiglass. A printed text, affixed to the wall beside a fire exit haphazardly covered in lurid red paint, might have been written by a sentient fire alarm: “Hello dong ding dong drriiiing,” it says. Such interventions are in keeping with the spirit of early works such as Dacht en Nacht.MUSEUM OPEN 24/24 (1997), in which the artist opened a museum for 24 hours, with bright lights at night and darkness during the daytime. At once disorienting, atmospheric, and tongue-in-cheek, Tuerlinckx’s works heighten the viewer’s awareness of how the meaning ascribed to art is conditioned by the contexts in which it is encountered. …

April 18, 2025 – Review

Lina Lapelytė’s “In The Dark, We Play”

Ben Eastham

The vestibule of The Cosmic House, the postmodernist fantasia realized by Charles Jencks in a West London townhouse, is ringed by William Stok’s frieze of a symposium of thinkers ranging from Imhotep to Hannah Arendt. Such is the colossal immodesty of the architect’s project—a model of all space and time compressed into five floors linked by a helical “sun stair”—that it’s only a surprise Jencks didn’t insist on being painted into the conversation: sharing a joke, perhaps, with John Donne and the Emperor Hirohito. This transhistorical vision provides the unlikely inspiration for Lina Lapelytė’s intervention into this family home-cum-cosmological model, realized in collaboration with Nouria Bah, Anat Ben-David, Angharad Davies, Sharon Gal, Rebecca Horrox, and Martynas Norvaišas.

Unlikely because the aesthetic commitments of the architect and artist seem so diametrically opposed. Jencks, who designed his domestic utopia with Maggie Keswick Jencks and Terry Farrell, was an unabashed maximalist for whom irony, syncretism, and pleasurable excess were foundational principles. Lapelytė’s installation, by contrast, is understated, austere, and entirely earnest. It comprises a dozen minimalist musical compositions—filmed in parts of the house ranging from its loo to its library—playing on screens placed discreetly into various nooks and crannies. The visitor finds …

April 16, 2025 – Review

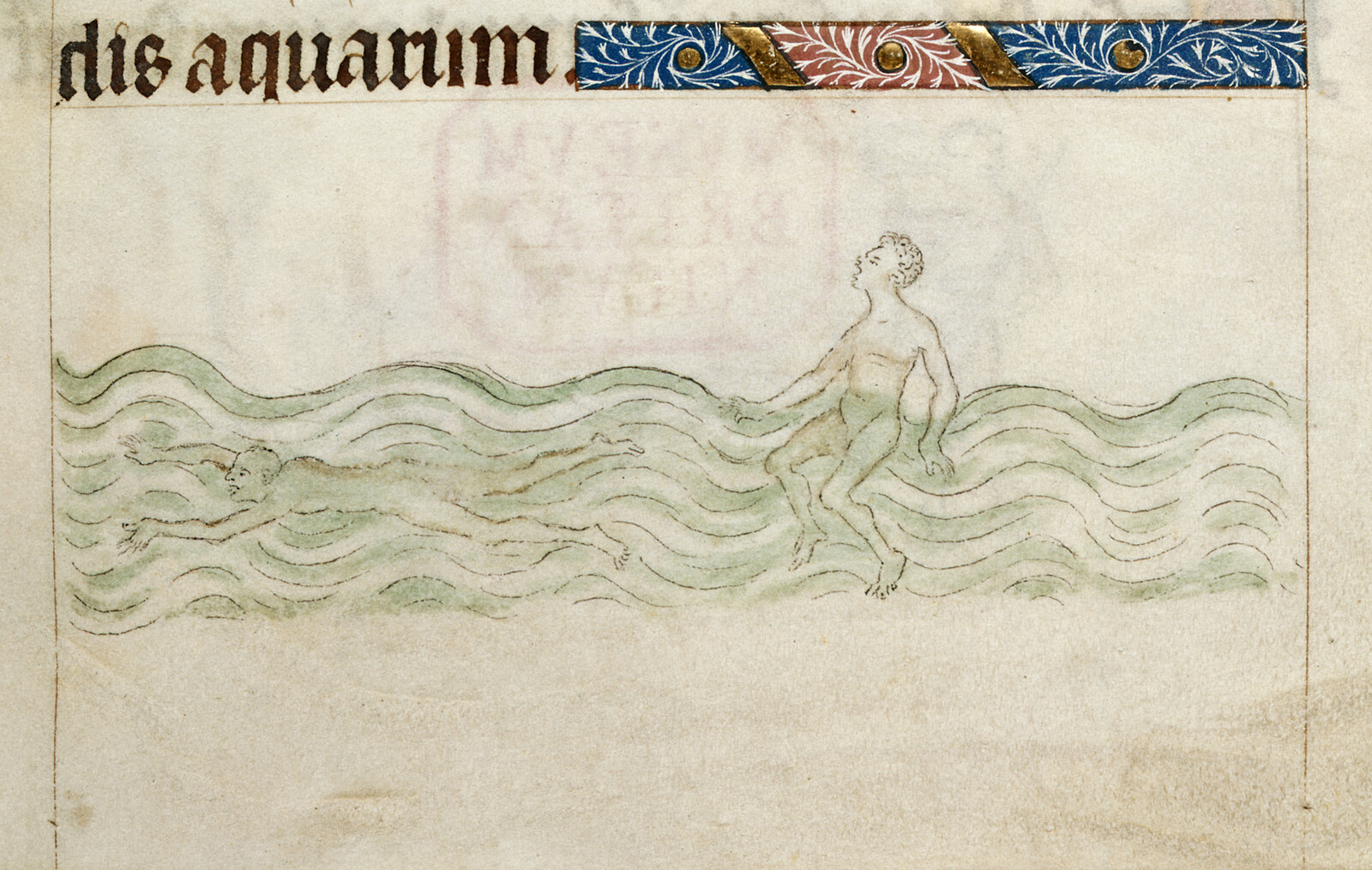

Mark Leckey’s “As Above So Below”

Laura McLean-Ferris

On my way into Lafayette, I encountered a quote by Mark Leckey on the wall near the entrance that had an echo of a content warning: “The works in the exhibition evoke intense emotions that make you unstable, untethered, that remove you from your normal place of function and towards something groundless, without horizon or a z-axis.” Okay, I thought. Also: how can a show actually live up to that kind of claim? Thirty minutes later, and I was experiencing a lurching, wheeling sensation and an elevated heart rate. I felt psychically and metabolically moved, but towards what?

Leckey has a remarkable gift for locating ecstatic feeling inherent to the experience of specific media, and amplifying this into something that can be shared: finding a way to transcendence through a symbolic system of brands, signs, and sounds (Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, 1999); an erotic desire to enter a world of images (Parade, 2003); the rush of imagining oneself dispersed across the spacetime of the internet (The Long Tail, 2008–9). In “As Above So Below” there are further varieties of euphoric experience, yet here, significantly, they are drawn into a parallel with medieval depictions of divine experience: the sublime and wonderful …

April 11, 2025 – Review

Hawaiʻi Triennial 2025, “Aloha Nō”

Emerson Goo

For the first time, the Hawaiʻi Triennial boasts an ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi title which stands alone with no English translation. Yet aloha, which here serves as a marker of cultural specificity, is also among the most globally familiar—that is to say, decontextualized and commodified—Hawaiian words. In Hawaiian, nō is as an intensifying particle akin to “very” or “strongly” which, when glossed in English, reads as a statement of negation. Curators Noelle M.K.Y. Kahanu, Wassan Al-Khudhairi, and Binna Choi thereby juxtapose understandings of aloha as love, generosity, and reciprocity against the possibilities created by defiance and refusal. They urge their audience to renew the potency of a word routinely taken for granted by Hawaiʻi residents and tourists alike, framing Hawaiʻi as a site where aloha is regenerated through artistic practices beyond its dereliction at the hands of a militouristic occupying state.

The destruction of Lahaina in the 2023 Maui wildfires weighs heavily on the exhibition. In a moving display of inter-island solidarity, works speaking to this context are found on all the participating islands in the triennial: Oʻahu, Maui, and the Big Island (Hawaiʻi Island). Hale Hoʻikeʻike at the Bailey House in Wailuku features filmmakers Sancia Miala Shiba Nash and Noah Keone …

April 9, 2025 – Review

Amy O’Neill’s “This’s and that’s”

Lauren O’Neill-Butler

Francisco Goya’s The Straw Manikin (1791–92) presents a carnival custom: a group of four women tossing a helpless male dummy into the air. Characteristically for carnival traditions and for Goya’s paintings, this ostensibly lighthearted scene is suffused with violence. The tight smiles on the women’s faces evoke a shared complicity, the straw doll’s neck appears to be broken from the game, a fantasy is being played out.

At Den Frei—Denmark’s oldest artists’ association, well known for its collaborative ethos—Amy O’Neill unpacks what the carnivalesque means today by uniting themes of production and performance, celebration and corruption. Installed near the entrance is STRAW MAN Vestment (all works 2025), one of three works which isolate Goya’s limp doll. Made of quilt tops and digitally printed fabric, O’Neill’s piece transforms the tortured figure into a prêt-à-porter object. The garment anchors the show, allowing the sightlines and angles that the artist creates around it to feel carefully measured.

Curated by Laura Gerdes-Miranda, in partnership with Line Ebert and Gianna Surangkanjanajai, the show features large-scale drawings, bespoke outfits (such as chasubles embellished with silkscreen imagery or iron-on transfers, snaps, and ribbons, along with papier-mâché masks and rope belts), and an analog slideshow. …

April 8, 2025 – Review

Valentin Noujaïm’s “PANTHEON”

Dylan Huw

Valentin Noujaïm’s “La Défense” trilogy (2022–25) opens with archival news footage about the construction of the Arche de la Défense in Paris, completed in 1989 to mark the bicentennial of the French Revolution. This introduction establishes the central subject of the films—the corrupted and corruptible spatial environment of Europe’s largest purpose-built business quarter—while betraying little of the extravagant range of stylistic and generic registers that Noujaïm goes on to employ in the trilogy. Over the course of these films, the artist’s emphases deviate from this district’s lived history, in favor of more speculative narratives which unfurl using tropes of body horror and arthouse sci-fi. The gray skyscraper-fantasia of La Défense emerges as a synecdoche for the vampiric properties of corporate capitalism everywhere, even while the films remain local to the racialized neoliberal logics of the French capital: the arch was one of Socialist president François Mitterrand’s “Grands Projets,” and the business quarter’s construction from the late fifties onwards precipitated the displacement of predominantly Arab communities.

After much acclaim for the first two films on the festival circuit, this exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel (which co-commissioned the third) offers the first opportunity to survey Noujaïm’s trilogy as a body of work, …

April 4, 2025 – Review

Sue Williamson’s “There’s something I must tell you”

Keely Shinners

In a photograph, two chairs, draped in white cloth, stand sentry around a rubble heap—old fences, shutters, doors. The chairs belong to the Ebrahim family. In 1981, the Apartheid government forcibly evicted the Ebrahims from their home, Manley Villa—one of the last to be demolished in District Six, a historically multiracial community in Cape Town that had been declared a “whites-only area” in 1966. Sue Williamson’s exhibition at the city’s Gowlett Gallery, “The Last Supper,” displayed detritus the artist (who is white) had collected from the demolition sites (prompting a visit to the show by police). That detritus is gone now, though photographs of the exhibition remain. Photographs and, miraculously, these chairs.

The chairs feature prominently in a new installation called Don’t let the sun catch you crying, created for Williamson’s first major retrospective, curated by Andrew Lamprecht. Nearby, former District Six residents and their descendants are captured in a series of photographs, enjoying a meal of cupcakes and cool drinks in the brush where the neighborhood once stood. Despite a 2018 Land Claims Court ruling that ordered the government to address land restitution claims, District Six remains largely undeveloped. The community continues to fight for the right to …

April 3, 2025 – Review

“Tribute to Abdel Hamid Baalbaki: Ode to the South”

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

The Lebanese artist Abdel Hamid Baalbaki painted four major murals in his lifetime. Baalbaki called them murals, but in reality they were large-scale oil or acrylic paintings on canvas that strived for monumentality. They combine references to historical events, religious rituals, and performative reenactments. Though aware of the Mexican muralists David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera when he painted these works in the 1970s, Baalbaki was inspired by the Iraqi modernists Jewad Selim and Kadhim Hayder, who had turned to archeology and mythology, a decade earlier, to form the elements of a new national culture.

For all their size, however, Baalbaki’s murals proved vulnerable. One of them, titled Ashura (1971), was either stolen or destroyed when the Institute of Fine Arts at Lebanon’s public university was ransacked during the country’s fifteen-year civil war. Another, titled The Fall of Al-Nassar (ca. 1972–74), was cut into pieces and likely discarded in Paris. The remaining two are now facing each other, like old friends, on either side of a small gallery, in a modest but revelatory tribute at Beirut’s Sursock Museum.

“Tribute to Abdel Hamid Baalbaki: Ode to the South” includes some forty paintings and red-chalk drawings. The first of its two …

April 2, 2025 – Editorial

Ghost stories

The Editors

Aby Warburg famously described art history as “ghost stories for grown-ups.” The implication is that every culture is haunted by its past, and most of all by those parts it has attempted to repress. Historical continuity, according to this model, is guaranteed only by the intermittent return of these unresolved impulses to disrupt any pattern that has settled into predictability. No history of culture can be boxed into perfectly sealed movements: so that the Renaissance in the western tradition shuffles off forever with the arrival of the Baroque, which cedes to Classicism, which is overthrown by Romanticism, which heralds the Modern, and so on, like so many actors invited onto the stage to deliver a monologue in turn. Rather, each must compete with their predecessors, who shout from the wings and threaten to invade the stage.

As we come to terms with the end of our own historical era, this feels particularly instructive. Rather than seeking out works of art that reinforce the dominant narrative of the present, the art historian—and their short-sighted accomplice, the critic—might instead be on the lookout for those that resist classification, that cannot be systematized, that are irrepressible because they are vital (Warburg called …

March 31, 2025 – Book Review

Laurent Stalder’s On Arrows

Isabelle Bucklow

“The only perfect building must be the factory, because that is built to house machines, not men,” announced Professor Silenus (a surrogate for Walter Gropius) in Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall (1928). Laurent Stalder’s volume of essays on postwar British architecture features many Silenus-sympathizers who would prefer the various substances and bodies moving through their buildings to be as reliable as machines. A diplomatic architectural historian—neither luddite nor techno-optimist—Stalder, too, is concerned with architecture vis-à-vis machines: most specifically in regard to the subsequent functioning and performance of buildings and their contents.

Noting the cultural and scientific precedents—from material innovation to discoveries in molecular structure—that have fostered new approaches to architecture and town-planning, Stalder’s book explores how postwar architects began to see buildings in terms of totalizing environments. Open-plan and glass promoted transparency, and sunlight and breeze were considered as important as bricks and mortar. What was at stake was “the control of a multilayered visual, climatic, spatial environment”: or, as László Moholy-Nagy put it, why should one “live between stone walls when one could live under the blue sky between green trees with all the advantages of perfect insulation?” That control began in the architectural plan, cohering in a specific …

March 28, 2025 – Review

Kosen Ohtsubo & Christian Kōun Alborz Oldham’s “Flower Planet”

Filipa Ramos

For the layperson, ikebana, a traditional Japanese technique of flower arrangement, strikes a mysterious balance between chaos and order, atemporality and contingency, structure and uncertainty. A floral interpretation of the harmonic principles of cosmic order particular to the national culture, ikebana can seem inscrutable to any viewer unfamiliar with its traditions.

Ikebana arrangements are also typically presented in religious, domestic, and private spaces, and so an exhibition devoted to the form in a contemporary art venue such as the Kunstverein München is unusual. They are also accompanied by aesthetic expectations and conventions. When it comes to the representation of flowers, no one wants ikebana to bear the same existential weight as a Flemish still life or Van Gogh’s fat sunflowers and trembling irises, all crammed into a terracotta jar. Even those with a lay understanding of the practice can recognize that asymmetry, sobriety, containment, and a careful, choreographic construction of negative space are key to ikebana, and that these values—and their underlying codes—are very different to those by which the western still life tradition is judged.

Indeed, the practice of ikebana contributed to the ultranationalistic imaginary of Japan, reaching its greatest popularity during the 1920s and ’30s. Reinforcing protocols and …

March 27, 2025 – Review

Sadao Hasegawa’s “English Companion Inc.”

Tom Denman

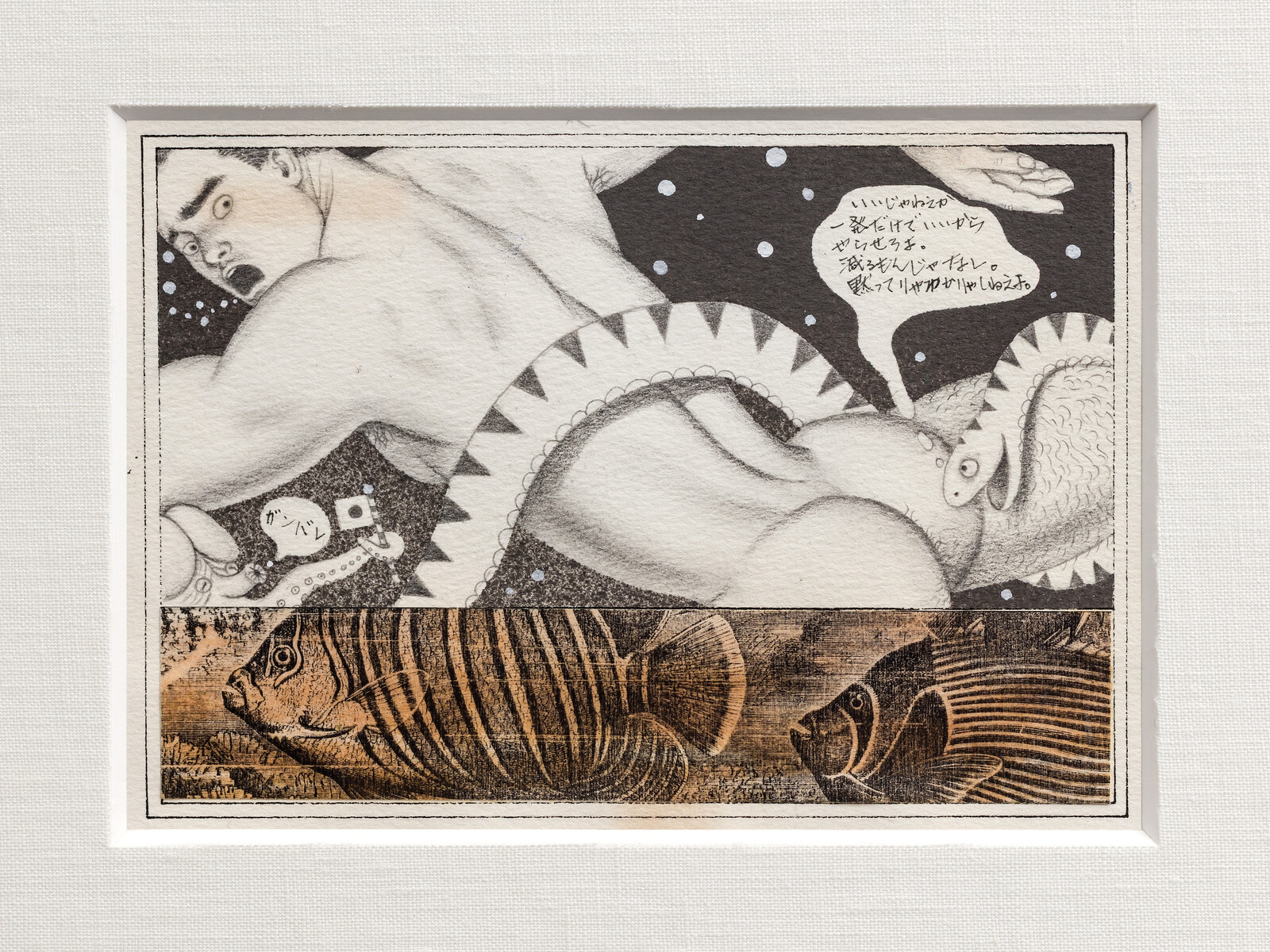

From the late 1970s until his death in 1999, Sadao Hasegawa was one of postwar Japan’s most prominent illustrators, and a major figure in the country’s burgeoning industry of gay magazines. This collaboration with Tokyo’s Gallery Naruyama—which has handled his estate since his suicide—is Hasegawa’s first solo show outside Japan: although his paintings and drawings were reproduced in magazines in the US, UK, and Australia, his concern that their erotic content would land him in trouble with Japanese customs prevented him from shipping them to arts institutions overseas. Suggestively titled after the corporate letterhead of paper on which he sketched, it presents a focused selection of works in a vitrine and on the walls of one small room, consisting mainly of designs for magazine prints—some of which still have their marked-up overlays.

In a 1995 letter from Hasegawa to Durk Dehner, founder of the Tom of Finland Foundation, he articulated, in English, an intention of using mainly Asian “motifs” to create a “universe of beauty” that “differs from [the] Western point of view.” This utopian project sums up the show’s focus, part of which involves Hasegawa assaying the politics of queer miscegenation between East and West. A preparatory drawing for …

March 25, 2025 – Review

“PinchukArtCentre Prize 2025”

Oliver Basciano

Everyone I meet in Kyiv is tired. Physically tired. Emotionally tired. Tired from the shrill loud whirl of the air raid app forcing them from sleep to the bomb shelters. Tired of the hours spent underground. Tired of the fear. I spoke to a woman on my night train from Moldova who had spent a week in Chișinău catching up on sleep.

It is therefore understandable that much of the work in the biennial PinchukArtCentre Prize—a gathering of twenty artists from across the country, all under 35, some displaced from their home regions to the safer west, some abroad temporarily—is bathed in a melancholic desire for calm. White is the recurring shade. In Mud Hut (2025), Anton Saenko has covered the entire gallery wall with the whitewashed clay mix used to build the titular countryside dwellings. Hung to this feature is one of the artist’s monochromes, also white. It is meditative, full of pathos, inviting the view to disappear, escape perhaps, into its pale frame.

A snow-white landscape by Mykhailo Alekseenko, a painting reminiscent of the land I had seen stretching out over nineteen hours on that train into Ukraine, takes the feeling further. Peaceful Landscape in a Nonexistent Museum …

March 21, 2025 – Review

“Archival Time On Our Retina”

Max Crosbie-Jones

One surprising legacy of the United States’ public diplomacy across Southeast Asia during the Cold War is an eighteen-minute film featuring dialect and music indigenous to Thailand’s northeast region. Produced by the United States Information Service (USIS), The Community Development Worker (1963) pairs black-and-white 16mm footage of the smartly dressed titular subject touring a dusty village on foot to a soundtrack of jaunty, laudatory songs. Scenes of him offering guidance to beaming villagers segue into footage of lectures, laborers digging sunbaked fields, and provincial officers orchestrating the rebuilding of a school. Meanwhile, the lyrics of the accompanying mor lam—a propulsive form of sung storytelling accompanied by a khaen (bamboo mouth organ)—beseech the people of Isaan, as this region is known, to not be lazy, and to work together to improve their community rather than wait for government.

This melodious attempt to ward off communism in Isaan demonstrates how the United States’ Cold War propagandizing included the co-opting of vernacular forms and local voices, as well as the invocation of rural stereotypes and center-periphery dynamics. Yet in the hands of Ukrit Sa-nguanhai—one of four artists contributing to this group exhibition at the Thai Film Archive on Bangkok’s outskirts—its local resonances are …

March 20, 2025 – Review

Lisa Alvarado’s “Shape of Artifact Time”

Alan Gilbert

Identities are constructed around borders that are themselves porous: identities not only border other identities, but ecologies, species, and objects as well. What is sometimes described as intersectionality might also be understood as interdependence: the vast network of relations—from microbiomes, to political economies, to geographies—in which any human subject is deeply enmeshed. In her work as both a visual artist and musician, Lisa Alvarado challenges the imposition of boundaries, whether between sight and sound, between Western traditions of abstract painting and Mexican textiles, or between home and displacement.

Born and raised in the border region of San Antonio, Texas, Alvarado had earlier Mexican American, landowning family members deported during the 1929–36 Mexican Repatriation, some of whom returned to the United States as migrant laborers. She studied painting as an undergraduate at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the early 2000s and experienced the city’s jazz and experimental music scenes, eventually joining Natural Information Society (led by Joshua Abrams), which self-describes as creating “long-form psychedelic environments informed by jazz, minimalism and traditional musics.” Contributing to this “psychedelic” quality are the series of paintings that Alvarado began producing for the band’s performances. Depending on the size of the stage, …

March 19, 2025 – Review

François Pain’s “Psychiatry is what Psychiatrists do”

Nicholas Gamso

In 1966, a young medical student named François Pain won an internship at the experimental Clinique de La Borde, outside the town of Cour-Cheverny in the Loire Valley. The clinic’s directors, Jean Oury and Félix Guattari, France’s leading “anti-psychiatrists,” invited students from around the country to join La Borde’s nurses, doctors, and patients—referred to as pensionnaires, or boarders—in building an informal lieu de vie on the grounds of an old château. There were no white coats, no padded walls, and the ethos was humanistic, horizontal, and self-regulating. Trained medical staff spent their days emptying ashtrays and pulling weeds, while pensionnaires held daily council meetings, organized festivals, and managed the château’s studios and café.

For the six years he stayed at the clinic, Pain’s job was to edit the house newsletter, La Borde Éclair. He also opened a printshop, and later, after a stint working in Paris, returned to set up a video club and atelier—he’d discovered the Sony Portapak, appealing for its “democratic” ease of use, during a visit to Vidéographe in Montreal in 1973. Over the next two decades, Pain made several short films about anti-psychiatry, including collaborations with pensionnaires (the wonderful comic feature The Crystal Wave, 1985), interviews …

March 18, 2025 – Review

Gabriel Orozco’s “Politécnico Nacional”

Gaby Cepeda

Gabriel Orozco’s first museum show in Mexico for almost twenty years seeks to answer a fundamental question: How does his practice work? As its title suggests, this career-spanning survey is heavily invested in the fact that Orozco operates across numerous media. “Politécnico Nacional” is the name of a prestigious public school in Mexico City and also, at least ostensibly, what Orozco currently identifies as: a poly (as in many) technic (as in media), national artist. It is, of course, this “national” part that has caused some aggravation among local critics. Orozco is the international artist of his generation, the prodigal son who refuted his Mexican-ness in his voyages on the global circuit, and at last returns to the national bosom—and embraces the state, no less.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. The show stratifies the museum’s four floors into elemental chapters: “Air,” “Earth,” “Water,” and “Compost.” It makes for a smart exhibition, especially the opening gallery. This first space is packed with objects, but precise curating means that it still feels fittingly airy. Right off the bat is a classic: Crazy Tourist (1991), the famed photograph of oranges sitting on ramshackle wooden tables somewhere in Brazil. I stopped to …

March 14, 2025 – Review

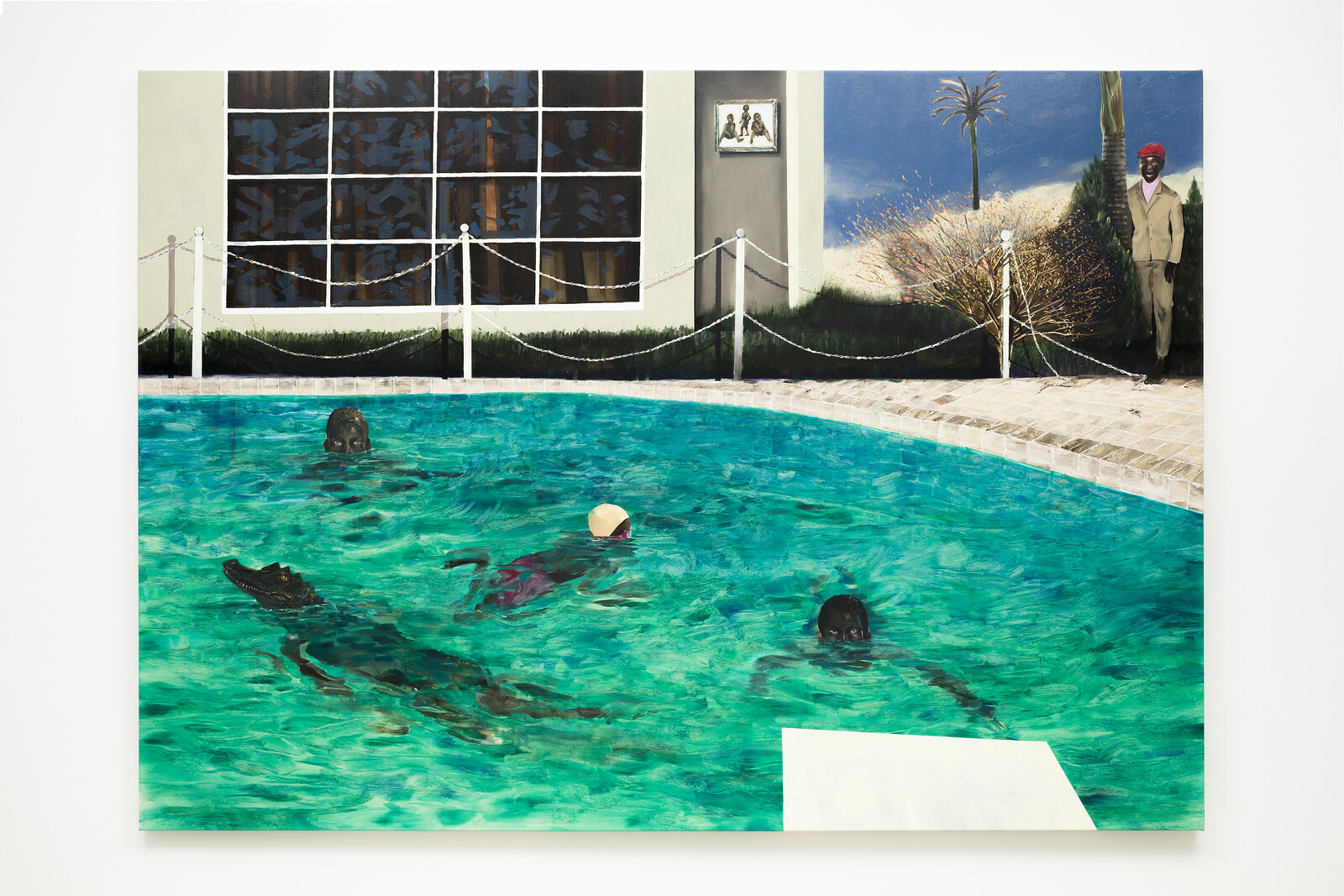

Noah Davis

Novuyo Moyo

This retrospective cements Noah Davis’s legacy as a multifaceted artist whose influence is only beginning to be felt and understood. Curated chronologically, it breaks the sections up in themes relevant to his practice and short life—Davis died in 2015, aged just 33—and gives a central place to The Underground Museum that he founded with his wife, the artist Karon Davis, in 2013. A cultural nerve center for the Los Angeles neighborhood of Arlington Heights, the community museum promoted access to art for all and, until its closure in 2022, extended the key concern with locality and social fabric that is essential to understanding Davis’s work.

That enthusiasm for and engagement with community is most obviously evident in Davis’s best-known paintings, which feature regular people, going about their lives, doing seemingly mundane things. He’d sometimes paint from memory, and at other times used photographs as reference material: his series “1975” was based on photos his mom took as a high school senior in Chicago. These paintings, at once intimate yet slightly detached, capture snapshots of ordinary lives and monumentalize them in his signature dry style. When not drawing directly from the quotidian, Davis turned to mythology and the imagination, and so …

March 13, 2025 – Review

Camille Henrot’s “A Number of Things”

Chris Murtha

Down the rabbit hole and rapidly fluctuating in size, the gigantic Alice cries a “pool of tears” in which, shortly afterwards, she nearly drowns. Camille Henrot invoked Lewis Carroll’s passage in Milkyways (2023), her book of essays on motherhood and art-making: “This push and pull of scale,” she wrote, “is something every mother experiences.” The French artist goes on to describe how parenting resurfaced her own repressed memories of childhood, implying that every adult contains a child. We can, perhaps, imagine Alice as representing both mother (large) and daughter (small).

In her first exhibition at Hauser & Wirth’s cavernous Chelsea space, Henrot produces comparably dramatic shifts in scale through oversized sculptures of toys and biomorphic abacuses, encouraging viewers to take the perspective of both adult and child. She covers the entire gallery with a padded and gridded green safety surface that resembles a “self-healing” cutting mat, a custom floor that unifies the disparate artworks as in a playground or a theater. Yet she has subtly distorted the grid, undermining the structuring order it purports to provide. If Henrot’s installation suggests a playscape, it is—like Wonderland—off-kilter, mysterious, and full of obstacles.

Greeting visitors at the exhibition’s entrance is a ragtag pack …

March 12, 2025 – Review

Malik Nejmi’s “Ter-Ter (Caring for the neighborhood)”

Océane Ragoucy

Malik Nejmi’s ambitious retrospective, co-curated with Louise Bras and presented in a deconsecrated twelfth-century church, poses a fundamental question: can architecture be a tool for collective and individual care? At the heart of this exhibition of photographs, videos, sculptures, installations, archival documents, and architectural ephemera is the neighborhood of La Source, on the outskirts of Orléans, where the Franco-Moroccan artist grew up. For more than three years, he carried out meticulous fieldwork in the area. In doing so, he combined autobiography with socio-historical research, the small story with the big picture. The planned demolition of Tower 17, an emblematic building in the area, was the catalyst for the project. Under the artist’s gaze, this disappearance becomes a symbol of a collective memory threatened with erasure.

The strength of the exhibition lies in its ability to deploy different temporalities around a single site. Before the demolition, Nejmi methodically documented the empty building through his series of large-format photographs (“Super-fenêtres,” 2024), in which the empty apartments still carry traces of past lives. A vertical orthophotograph of the façade (Orthophotographie, 2023), produced with the aid of large scanning devices, offers an overall view of the building, transforming architecture into an aesthetic subject in …

March 10, 2025 – Review

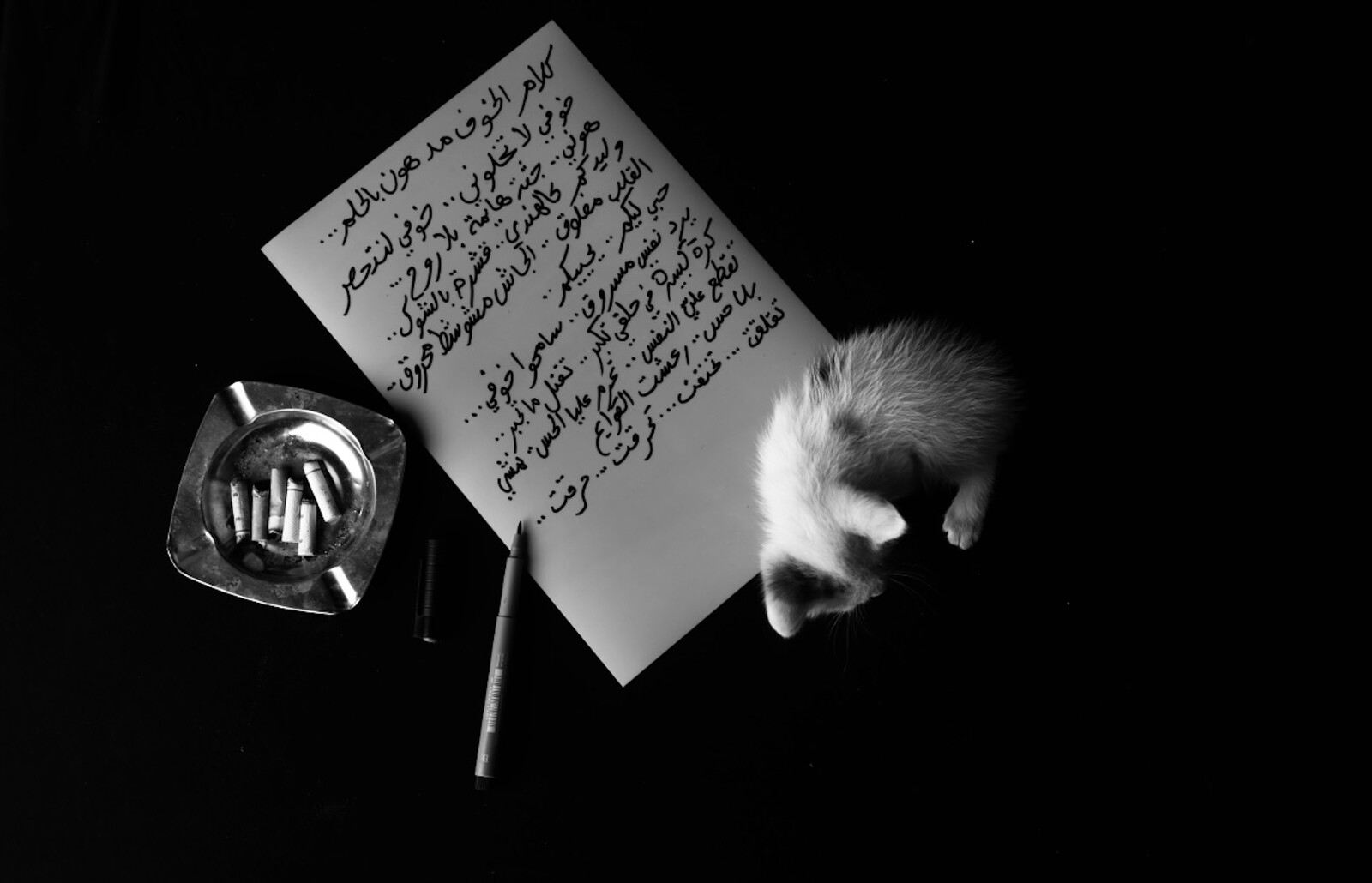

“Screen Memories”

Leo Goldsmith

“It did not happen.” Flickering across one of the screens in Huda Takriti’s Starry Nights / Or, of that night when stars disappeared (2025), these words haunt this exhibition of three artists from across the Arab world. Curated by May Makki, the show borrows its title from Freud’s 1899 essay of the same name, in which the “father of psychoanalysis” questions the processes by which early memories are transmuted into other forms, false recollections, and allusive narratives, that are more palatable to the conscious mind and “screen” us from the past. “It may indeed be questioned whether we have any memories at all from our childhood: memories relating to our childhood may be all that we possess,” Freud writes. We cannot remember, only project.

Misinformation, gaslighting, erasure. What were for Freud problems for the individual and her unconscious are now a vastly more generalized, more literal phenomenon. The real-time operations of a networked and globalized media landscape, obscuring very real violence with smoke and mirrors, have relieved our superegos of the task of repression and fabulation, as Israel’s genocidal campaign in Gaza has made starkly clear. Freud’s screen, a simple metaphor for memory’s occlusions, has now mutated into a ubiquitous …

March 7, 2025 – Review

Mélanie Courtinat’s “The Siren”

Jonathan T. D. Neil

I lost a week of my college life to the fully immersive exploratory puzzle game Myst when it hit CD-ROM drives in 1993. And I lost another week to Myst’s sequel, Riven, when I was in grad school. By 2004 I was well on my way to building an addiction to the first-person-shooter game Half-Life 2, sessions of which I rationalized as self-administered rewards for writing a few pages of my dissertation. Later that same year, after an all-night stint playing Call of Duty and emerging into the gray light of a Manhattan winter morning with claim to neither sleep nor sexual conquest, I left “gaming” behind.

Described by Mélanie Courtinat, a Paris-based artist and art director, as an “interactive experience,” The Siren (2024) is a video game of sorts, but one that is intended, as most such “art” games are, to induce in the player a self-consciousness about what it means to play such a game and the mechanics of narrative-meaning that attend to gameplay itself. Produced using Unreal Engine, an industry-leading programme for creating immersive digital 3D environments, The Siren has the look and feel of other contemporary adventure games built with the same engine, such as Chivalry …

March 4, 2025 – Editorial

Home from home

The Editors

One of the great attractions of contemporary art at the beginning of this century was its hospitality to other disciplines, especially those without the economic advantages afforded by its remarkably resilient attribution of value to unique objects (or strictly limited reproductions). So it was that—as the music and publishing industries were left scrambling by the advent of online marketplaces—galleries and museums in many cities stepped in to fill the space left by the closure of independent bookshops, concert venues, fringe theaters, and other victims of falling sales, new distribution models, and rising rents.

A poet might at that time have been paid more to read at an exhibition opening than to publish their debut collection; experimental musicians found receptive audiences among the young people who showed up to art events for the ambience. That the art world became a second home for those writers, dancers, musicians, theoreticians, activists, and academics struggling to find a place in their own cash-strapped, conservative, and increasingly risk-averse fields coincided with, and accelerated, the collapse of the visual arts’ own disciplinary borders. So that these exiles in many cases became the artists—not to mention the curators, critics, and gallerists—who would do so much to shape …

March 1, 2025 – Book Review

Ellen Levy’s A Book about Ray

Francesca Wade

I found myself in the Ray Johnson archive by accident. Last December, I attended a screening of How to Draw a Bunny (2002), Andrew L. Moore and John Walter’s haunting, fascinating documentary about the elusive figure once described as “New York’s most famous unknown artist” (the titular proposition, Johnson explains with characteristic deadpan, is “basically very simple. You draw a circle and add some ears”). I was still thinking about Ray the next afternoon, as I wandered down Sixty-Ninth Street. So it felt like one of his own trademark coincidences when—having entered David Zwirner Gallery to see a selection of Noah Davis’s collages—I spotted a brass plaque directing me up another flight of stairs to the floor where Johnson’s estate headquarters. Shelves are filled with his books; his cut-ups and collages crowd the walls; a bust, half its face covered with Johnson’s signature bunny head, perches precariously in a corner. I couldn’t help but remember a scene at the end of How to Draw a Bunny, in which Johnson’s friends enter his home shortly after his body was discovered off the coast of Sag Harbor, Long Island (he had been spotted, on January 13, 1995, diving off a bridge and …

February 28, 2025 – Feature

On Sagarika Sundaram

Pramodha Weerasekera

Sagarika Sundaram and I both had modest period-marking ceremonies, in India and Sri Lanka respectively, when we first started menstruating. Such rite-of-passage ceremonies are passed on from generation to generation in South Asian communities across the globe. Their regional differences—demonstrated in her Chennai-based ceremony and mine in Colombo—dominated my first conversation with Sundaram, whose art practice draws on such re-evaluations of her South Indian background, among other subjects.

She and I are both familiar with the act of washing saris and letting them dry on a wooden pole or nylon rope hung from one corner of a room to another. These precious six-to-seven yards of cloth provide comfort through the seasons and are a unique mode of self-expression. Sometimes hung like paintings on the wall and other times suspended from the ceiling like sculptures, Sundaram’s large-scale, textile works—with their bright colors, voluminous fabrics, relationship to ritual, and intimations of the female body—seem to me to draw on some of the same ritual functions of the sari in South Asian communities.

Sundaram’s Released Form (2024) opens and closes with a glimpse into the inside of an unfolded sari. The viewer is invited to take a stroll through the work and experience …

February 25, 2025 – Review

Ho Tzu Nyen’s “Time & the Tiger”

Xenia Benivolski

Ho Tzu Nyen has long been preoccupied with the way history repeats in disguise: empire folds into empire, technologies of governance advance, and yet the conditions of control remain eerily familiar. In the Luxembourg iteration of the Singaporean artist and filmmaker’s mid-career retrospective, time is an instrument of power that measures mechanical precision against mythological recurrence: Ho’s work asks what it means to resist its rhythm.

Entering the exhibition, an arrangement of five screens laid out before woven mats suggests both an intimate gathering and a formal ritual. Collectively titled Hotel Aporia (2019), these video vignettes recount fragmented stories from Southeast Asian nations during the Japanese occupation, the faces of the characters deliberately blurred and anonymized by the artist. Hotel Aporia proposes that empire is not only about land but about temporality: to control time is to control narrative, labor, and even perception itself. Anonymity is not just an erasure but a symptom of the empire’s ability to reduce individual subjects to the status of interchangeable bodies, caught in the loops of time.

T for Time: Timepieces (2023–ongoing) gathers a constellation of luminous images—Sisyphus pushing his rock, a river flowing endlessly, a beating heart—on screens in a dark room, leading …

February 24, 2025 – Feature

Singapore Art Week

Adeline Chia

A storm is raging in Singapore. Waves break against park benches and dash against trees. Public housing estates are half-submerged; bobbing on the water surface are abandoned lifeboats and jackets. With Disaster-free (2024), featuring footage generated with the help of AI, artist Ong Kian Peng has created a Singaporean disaster movie, in which rising sea levels have transformed the developed island-state into a gray, glimmering water world that we scan through the eyes of a single survivor paddling around in a kayak. Amid an unseasonally late monsoon season in January, I found this end-of-days scenario a calming respite in this year’s frenetic, more-is-more, soft-power flex of a Singapore Art Week (SAW). The institution, in its thirteenth edition and styled as “Southeast Asia’s pinnacle visual arts event,” packed more than 130 events into a ten-day run in venues across the island, including galleries, units in several dingy malls, and a miniature gallery with tiny artworks strapped onto the back of a roving artist.

Anchoring SAW are two art fairs: the flagship ART SG, in its third and smallest edition with 105 galleries at the Marina Bay Sands, and the smaller S.E.A Focus fair, showing Southeast Asian art in a boothless, free-flowing …

February 20, 2025 – Review

“The Ecologies of Peace II”

Evan Moffitt

One month after the second part of “Ecologies of Peace” opened in Cordoba, much of Spain was underwater. On October 29, more than an average year’s rain fell along the country’s southern and eastern coasts, killing over 200 people. Days later, crowds in Valencia pelted King Felipe VI and Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez with mud, blaming them for the state’s lack of emergency preparedness. The worst natural disaster in a generation became a political crisis.

If the ruling classes continue to prove themselves unwilling to address the climate emergency, then it’s fair to say that artists aren’t going to save the world either. But this show at C3A proceeds from the limited if hopeful assumption that they might be able to make a difference. Half of a group exhibition in two acts, “Ecologies of Peace” emerged from a series of partnerships between TBA21 and underfunded regional institutions, and at first glance, its title shares a sunny vagueness familiar from biennials in other parts of the world. Curated by Daniela Zyman, it claims to focus on “practices of mourning and forgiveness,” though, for the most part, it illustrates the scale of the devastation that calls for them.

“One has to learn …

February 19, 2025 – Review

Ahmad Sadali’s “Bound to the Earth, Aspiring to the Sky”

Innas Tsuroiya

Alongside pioneering abstract art in Indonesia, Ahmad Sadali was an influential scholar and religious thinker, a public muralist who strived to ignite the spirit of liberation during the 1945 war, a national representative at UNESCO, an observer at the Bandung Conference of 1955, and an orator at Jummah prayers who gave a celebrated speech at Istiqlal Mosque, Jakarta, in 1975. Yet even before his death in 1987, his legacy—like that of the Bandung School with which he was affiliated—was dogged by controversy over its relationship to western art histories.

“Bound to the Earth, Aspiring to the Sky,” held in a gallery owned by one of his former students, is timed to celebrate the centenary of Sadali’s birth and grouped according to the artist’s formal tendencies—from simple geometries to golden ornaments—instead of a rigid chronology. In the larger of the gallery’s two rooms are forty-five canvases that evidence the artist’s distinctive styles, from the still lifes and Cubist styling of his early career, to later works incorporating Quran verses and the Names of God into calligraphic abstractions. The show draws attention to a controversy begun in 1954, when art critic Trisno Sumardjo argued that a group show of Bandung-trained artists “served …

February 14, 2025 – Feature

Godlike and free?

R.H. Lossin

This is the second part of an essay by R.H. Lossin on the relationship between art, artificial intelligence, and emerging forms of hegemony. The first instalment was published on January 17 and can be accessed here.

Rashaad Newsome debuted “social humanoid artificial intelligence” Being at LACMA in 2019. The “robotic griot” (pronouns they/them) initially functioned as a guide to gallery visitors, and was designed “with agency in mind.” This meant that Being, unlike most service employees, wouldn’t respond predictably to user demands, but instead could “go rogue.” Other iterations of Being, trained on different data, have offered culturally sensitive app-based therapy to address experiences of racism, and led decolonial workshops. The major political claim made by Being is that it is an AI trained on a “counterhegemonic” dataset made up of “alternate histories and archives such as abolitionist, queer, and feminist texts” by Paulo Freire, Cornel West, bell hooks, and others. The dataset is organized using “non-Western indexing methods” (although it is unclear exactly what this means in relation to texts written in English and Portuguese).

Being is visually represented in a humanoid animation whose movements were partly derived from “the gestures and movements of vogue practitioners proficient in styles ranging …

February 13, 2025 – Review

Sharjah Biennial 16, “to carry”

Ben Eastham

Nicholas Thomas has characterized Paul Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897) as a “success as a painting, but a failure as a work of art.” Which is to say that while it dazzles through its arrangement of color and form, it travesties the Tahitian culture that it purports to depict and offers no meaningful response to the grand questions of its title. The phrase recurred to me throughout this sixteenth edition of the Sharjah Biennial—curated by Natasha Ginwala, Amal Khalaf, Zeynep Öz, Alia Swastika, and Megan Tamati-Quennell—with its emphasis on work that is, by contrast, firmly grounded in its cultural contexts and unambiguous in its ethical commitments. But it is less clear that all of them fulfil the first part of Thomas’s equation, and triumph on their own terms as sculptures, videos, installations, or any of the other aesthetic strategies through which it is possible “to carry”—as the exhibition’s title puts it—ideas, principles, and feelings across the borders separating people, communities, and cultures.

Mangku Muriati’s paintings succeed on both counts. Drawing on the traditions of Balinese puppet theater, the new commissions exhibited on Calligraphy Square, in Sharjah’s reconstructed historic …

February 11, 2025 – Review

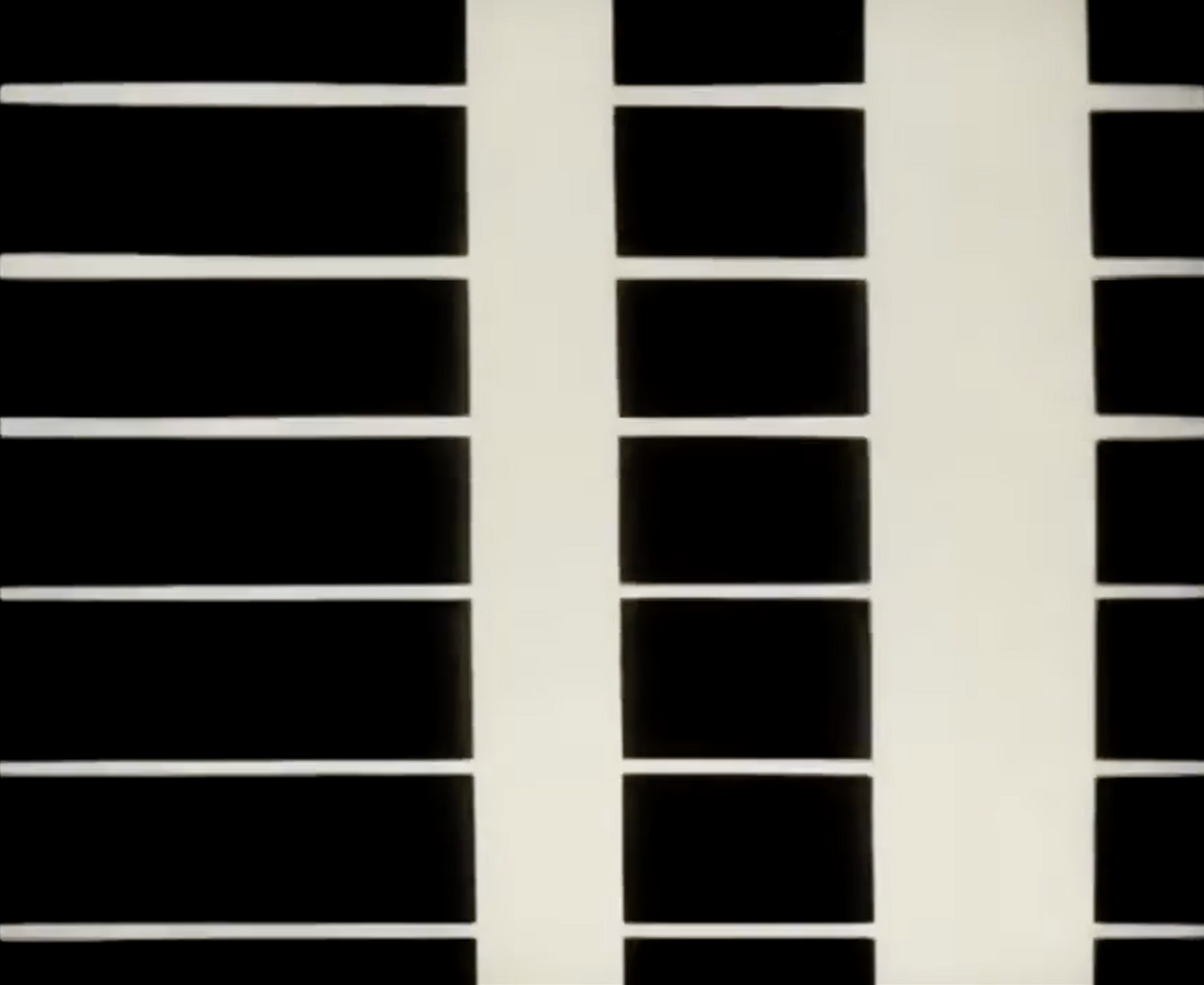

“Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet”

Brian Dillon

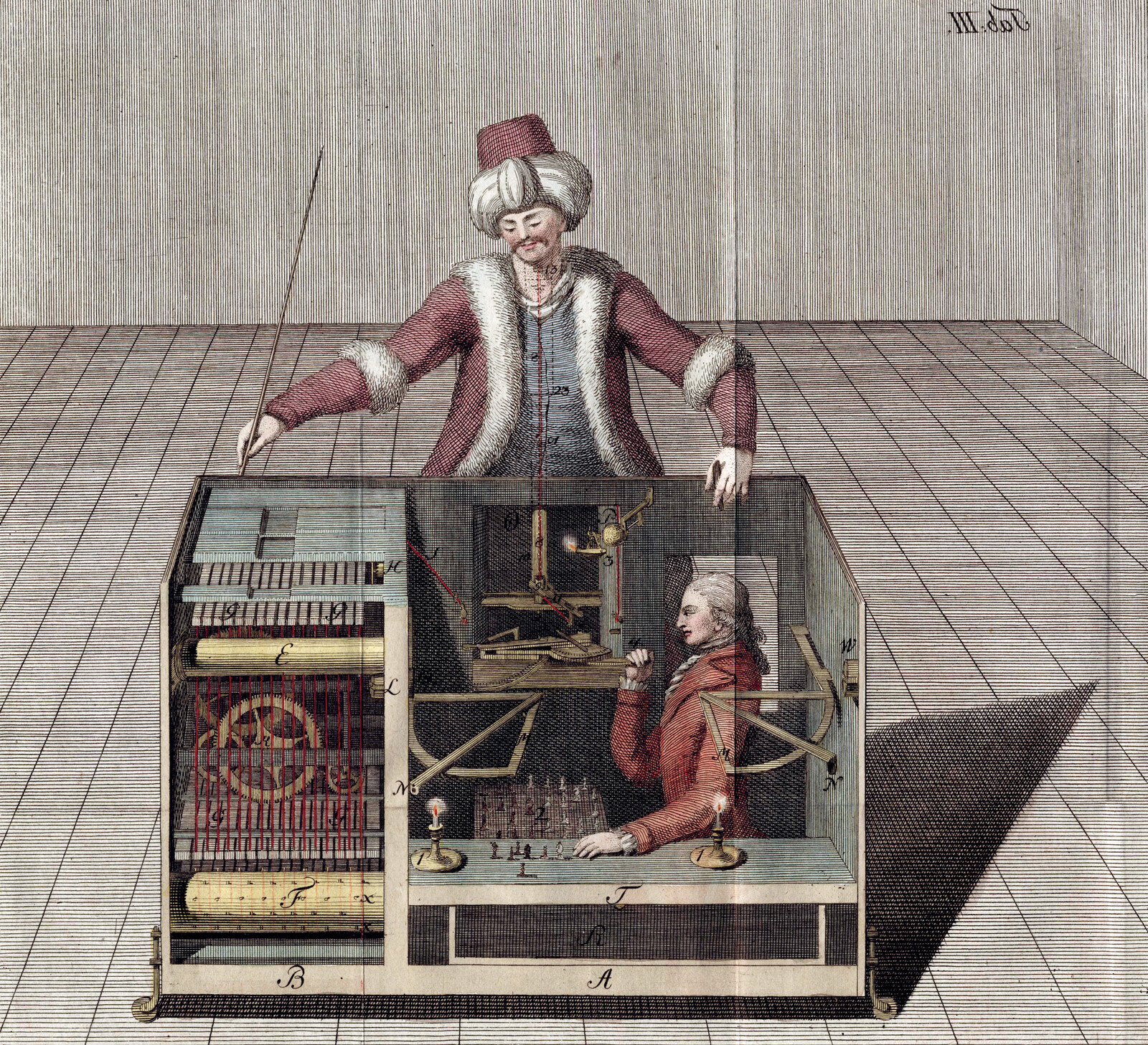

Imagine a historical juncture when machines promised to annex much tedious labor, manual or mental; to gather and strew the vast array of human knowledge at speeds and scale not dreamed of in our present technology; to pilot our imaginations towards new form and content in the arts, even new emotions and sensations. And at the same time threaten to steal our jobs and loot our private lives, tell us lies and fill our world with futuristic kitsch or inhuman austerity. Imagine if certain grim technicians enriched and refashioned themselves as prophets of this transmutation. And so on—the time of course is our own and not. It might be the post-WWII rise of techno-rationalism and information, the thrill of personal computing in the early 1980s, internet boosterism a decade later, the present perplex of competing perspectives on AI. Or the mid-nineteenth century, with its steam trains, telegraphs, and offset printing presses. In a crude history of modernity, the bourgeoisie is always rising, and technology the ambivalent object of faith and foreboding.

In other words, “Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet”—a survey that runs from the 1950s to the early 1990s, and commendably foregrounds artists and movements from Latin …

February 10, 2025 – Review

Climate Propagandas Congregation

Stephanie Bailey

The two-day Climate Propagandas Congregation was marked by urgency. Organized by Basis Voor Actuele Kunst (BAK) and artist Jonas Staal, it was the final event before BAK’s defunding by the Utrecht municipality and Dutch Council for Culture, reflecting a trend of arts institutions buckling under economic and political pressures, all while western governments openly flout international law and climate change wreaks planetary havoc. Welcoming a packed audience, BAK director Maria Hlavajova described her reaction when she learned of the institution’s fate: “The question spinning in my head, ‘How can we be more?,’ filled me with a sense of possibility, against all odds.”

That unshakable hope mirrored the will of artists, activists, cultural workers, theorists, and organizers who gathered in an aqua-carpeted “immersive diorama” to imagine ways of propagating radically egalitarian futures in an increasingly asymmetric present. Designed by Staal to invoke the Neoproterozoic Era’s Ediacaran period, described by geologist Mark McMenamin as a “pre-socialist socialist ecology,” giant painted biota adorned wood-frame podiums and stands around the auditorium, with larger specimens bearing the heads of historical revolutionaries like Ho Chi Minh, Eleanor Marx, and Thomas Sankara, to visualize the deep time of collective struggle.

As noted in Staal’s 2022 video essay …

February 7, 2025 – Review

Augustas Serapinas’s “Pine, Spruce and Aspen”

Michael Kurtz

As much arsonist as archivist, Augustas Serapinas takes an irreverent approach to remnants of the past. In 2012 he transformed student artworks discarded at the Estonian Academy in Tallinn into strange-looking gym equipment. For the inaugural exhibition of his London gallery Emalin in 2016, he repurposed materials left by the locksmith who previously occupied the building to create a functioning sauna. And in 2018 he invited children of workers from a decommissioned nuclear power station in his native Lithuania to create a sculpture using rubble from the Soviet-era site. In each fraught context, he intervenes with light-hearted acts of creative destruction, fostering new forms of sociability and use value rather than worshipping at the altar of cultural heritage.

An ongoing strand of Serapinas’s practice involves acquiring and pulling apart dilapidated log-and-shingle buildings, reconfiguring and sometimes charring the scavenged materials, then presenting them in exhibition spaces. Examples of this architectural vernacular survive from as long ago as the nineteenth century in Lithuania as well as over the border in Poland and Belarus. They are prevalent in and around the Polish city of Białystok and feature throughout his current show, filling the Galeria Arsenał elektrownia with the musky smells of damp wood …

February 6, 2025 – Review

Michael Asher

Travis Diehl

Would you pay to have less property? Patrons of Michael Asher did. In 1979, collectors Elyse and Stanley Grinstein commissioned him to make a work for their Brentwood home, adding to a semiprivate showcase that included arrangements of yellow stripes by Daniel Buren and huge redwood logs by Richard Serra. Asher’s untitled piece stipulated that a section of a wall marking the property line be demolished and rebuilt eleven inches inwards, effectively ceding a notch of yard to their neighbors. The work couldn’t be moved or sold.

Asher, who died in 2012, may seem like one of the drier conceptual artists of his generation. His work was usually temporary and survives largely through documents and writing. His most famous pieces involved removing the front wall of a gallery or rebuilding every temporary wall ever installed in a museum. Yet a current survey at Artists Space, despite comprising mostly ephemera including printed matter, notes, and schematics (such as architectural plans for the Grinstein’s modified wall), captures the humor that made Asher so influential.

The Grinstein work, Asher’s only private commission, typifies the artist’s puckish approach to what came to be known as institutional critique. His site-specific interventions were often something of …

February 5, 2025 – Editorial

News from elsewhere

The Editors

The art historian Thierry de Duve has characterized Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain as a “telegram” sent out in 1917 and only properly received and understood by a later generation, among whom it inspired the artistic revolutions of the 1960s. We might think of it less as an artwork authored “by” Duchamp, de Duve proposes, and more as a communication “from” him to artists of like intelligence and temperament, the majority of whom had yet to be born. It calls to mind those “lost” early radio transmissions that, despite not having been recorded on tape, continue faintly to bounce around the earth’s atmosphere, such that they might still be retrieved—and decoded—by someone with appropriately sensitive antennae tuned to precisely the right frequency.

That works of art are missives to be broadcast into the ether or dropped into the post (without knowing when or by whom they will be read) is an idea that rewards wider application. When the present is so bewildering—has not transpired as the received communications led us to expect—it might be helpful to comb back through the correspondence to see if some crucial message was missed. Maria Dimitrova’s recently published piece on the textile designer Anna Andreeva, for instance, …

February 3, 2025 – Book Review

Kevin Killian’s Selected Amazon Reviews

Ben Eastham

What is “literature,” and how is it distinguished from criticism, gossip, promotional material? Is it contaminated or invigorated by its overlap with these other forms of writing? Might literature be both creative and commercial, and, for that matter, throwaway and timeless, autobiography and fiction, local and universal, critical and compassionate, tongue-in-cheek and life-or-death? Are words on the walls of toilet stalls, on social media, on online marketplaces as worthy of the honorific as the products of the literary publishing industry? This selection of Kevin Killian’s nearly 2,400 product reviews for Amazon does not answer these questions so much as undermine the basic assumption on which they are founded: why are we so eager to ascribe value to writing according to its category, rather than attending to the writing itself?

We learn from an afterword by Dodie Bellamy, to whom Killian was married for over thirty years, that her fellow member of San Francisco’s New Narrative movement started leaving reviews on Amazon in the wake of a heart attack in 2003. A practice intended to ease his way back into writing soon became more than a means to an end, to judge by the frequency of his contributions (sometimes multiple times …

January 30, 2025 – Review

“Collective Threads: Anna Andreeva at the Red Rose Silk Factory”

Maria Dimitrova

Looking at works from an unfamiliar world, we need the world as much as the work to understand what we are seeing. When Aleksandr Deineka’s grand-scale painting Textile Workers (1927) was exhibited in the Royal Academy in London in 2017, a critic described it as futuristic, likening the female factory workers to sci-fi robots. Criticizing the acute anachronism of this interpretation in the preface of her book on Deineka, art historian Christina Kiaer acknowledged the difficulty in reading Soviet paintings today: “To our eyes, unfamiliar with images of labor, these working women are strange harbingers of an unknown future imagined from the outmoded pasts of both Communism and modernist painting.” Placing Deineka’s paintings within their original sociopolitical context, Kiaer’s aim was to restore their legibility beyond the “prevailing visual codes of capitalism” and reveal something often lost on contemporary eyes.

A similar reconstructive logic underpins the first retrospective of Soviet textile artist Anna Andreeva, curated by Kiaer at the Museum of Modern Art-Costakis Collection in Thessaloniki. Lauded in the USSR, including with the prestigious Repin Prize for lifetime achievement in 1972, Andreeva was virtually unknown in the West until in 2018, ten years after her death, the Museum of Modern …

January 29, 2025 – Feature

Condo London 2025

Orit Gat

“I always arrive at something new out of desperation.” This was Anna Zemánková’s description of how she began to make drawings in satin when she ran out of paper. The resulting collages use textile colors, ballpoint pen, and acrylic to create the shapes of flowers and plants. They are tender and surprising, a new and shimmering nature. Zemánková, born in Austria-Hungary in 1908, was self-taught: a dental assistant who began making art after a bout of depression following the death of one of her children. Drawings of flowers might traditionally be defined as “women’s work”; better to say that it was the conditions under which she made art—pressured to take a trade rather than go to art school, raising a family, only making work as a response to personal tragedy—that defined her labor as such.

Eight of Zemánková’s flower pieces, which were also shown at the 2013 and 2024 editions of the Venice Biennale, were brought to London by Sophie Tappeiner as part of Condo, a project in which twenty-two London galleries host twenty-seven peer spaces from around the world. The match-ups vary. The Approach handed their annex space to Vienna’s Tappeiner and their upstairs to Zurich gallery Philipp Zollinger, …

January 24, 2025 – Review

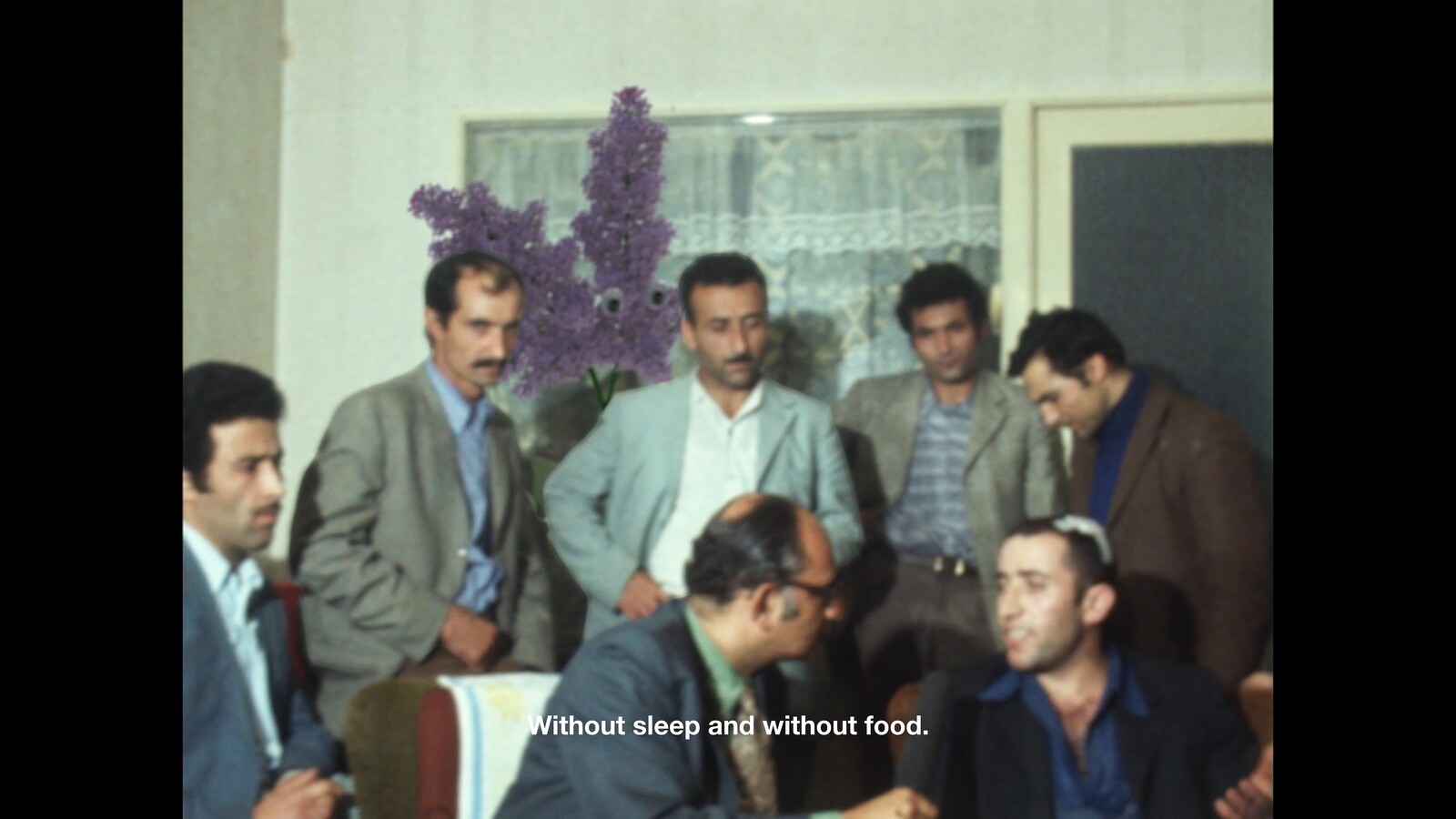

Cihad Caner’s “(Re)membering the riots in Afrikaanderwijk in 1972 or guest, host, ghos-ti”

Musoke Nalwoga

In August 1972, a Turkish landlord evicted a Dutch woman living in the Afrikaanderwijk neighborhood of Rotterdam. This event became the trigger for riots which saw people from all over the country pour into the Afrikaanderwijk to watch as anti-immigration protesters destroyed homes in the majority-immigrant neighborhood. Ten years ago, the Turkish artist Cihad Caner moved to Afrikaanderwijk. Having happened upon the story of this riot, he attempted to reconstruct a collective understanding of its history with his 2023 film (Re)membering the riots in Afrikaanderwijk in 1972 or guest, host, ghos-ti.

The exhibition is sparse. A white room is scattered with archival images scratched into red MDF plates. Inscribed into some of the plates are scenes showing people rioting on the streets of Afrikaanderwijk; others show the inside of immigrant homes that are visibly looted and in disarray. With this simple gesture, Caner places the Dutch rioters as the outsiders on the streets and the immigrant workers as the insiders in their homes—probing the latter’s status as outsiders in the Dutch collective psyche. The viewer, meanwhile, is made to oscillate between being on the inside and the outside as they navigate the installation.

Caner is an artist of Turkish descent, …

January 23, 2025 – Feature

On Nolan Oswald Dennis

Sean O’Toole

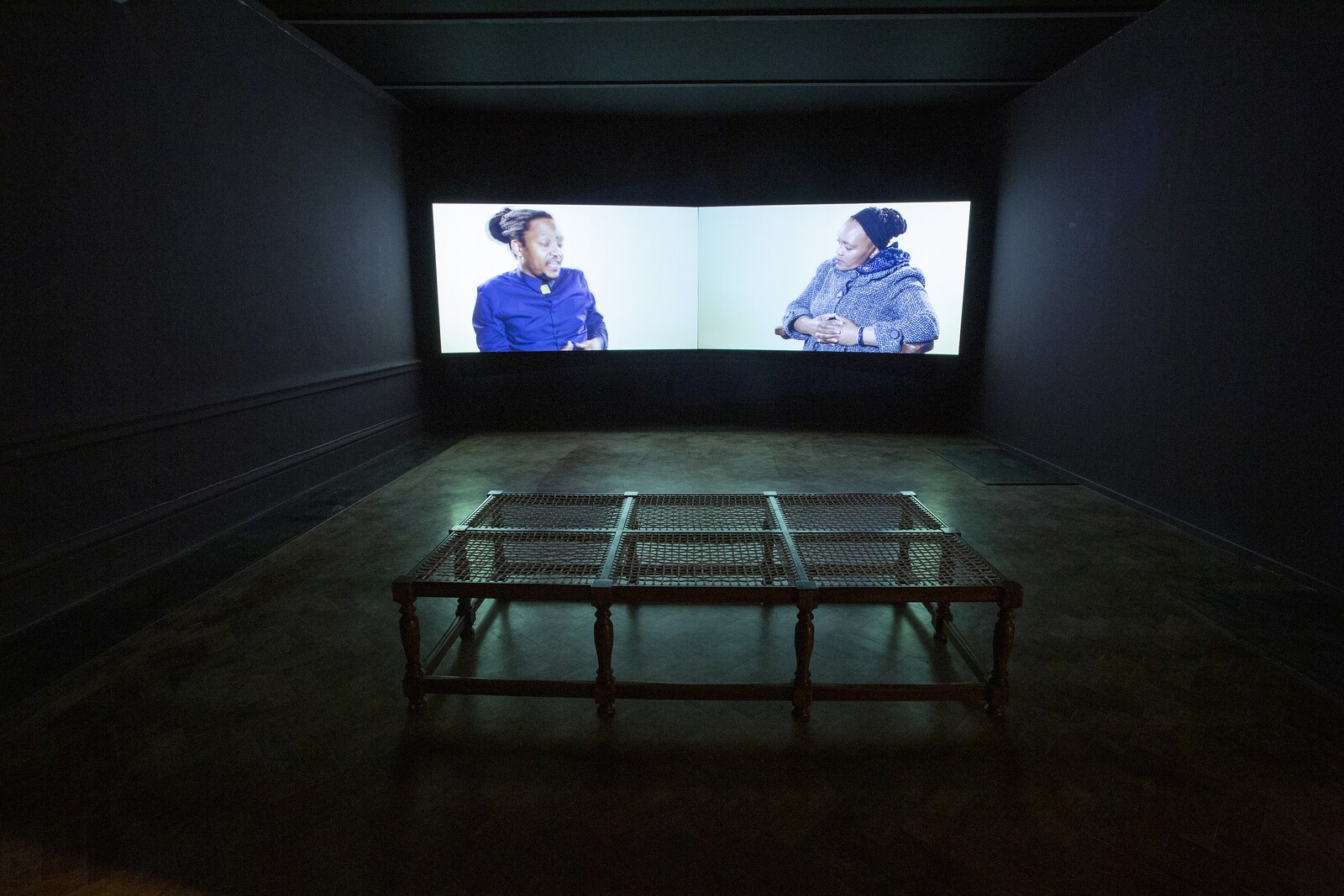

Over the past three years, Nolan Oswald Dennis has gained significant international recognition, showcasing their diagrammatic and collaborative practice at two prominent Swiss museums in 2024 alone. The artist’s probative, sometimes opaque work—a mix of drawing, sculpture, film, and installation—also appeared in recent editions of biennales in Dakar, Liverpool, São Paulo, and Shanghai. These career milestones were bookended in late 2024 by an event closer to home: the artist’s first museum solo exhibition in South Africa. Organized by Cape Town’s Zeitz MOCAA, “Understudies” offers a broad overview of Dennis’s multifaceted practice, its speculative methods, iterative processes, rootedness in collaboration, and overall inclination towards “keeping a question open for as long as possible,” as the artist put it to me during a series of online conversations and email exchanges.

Curated by Thato Mogotsi, Dennis’s early-career survey includes small drawings on grid paper, variously sized hard and soft sculptures portraying globes (a recurring motif in their practice), a low-tech receipt printer issuing aphoristic chunks of text by anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko, as well as a drawing installation depicting a celestial body. The selection affirms the importance of models, diagrams, annotations, and simulations as forms for prompting critical thinking. Partly inspired by the …

January 22, 2025 – Review

Hans Haacke’s “Retrospective”

Jörg Heiser

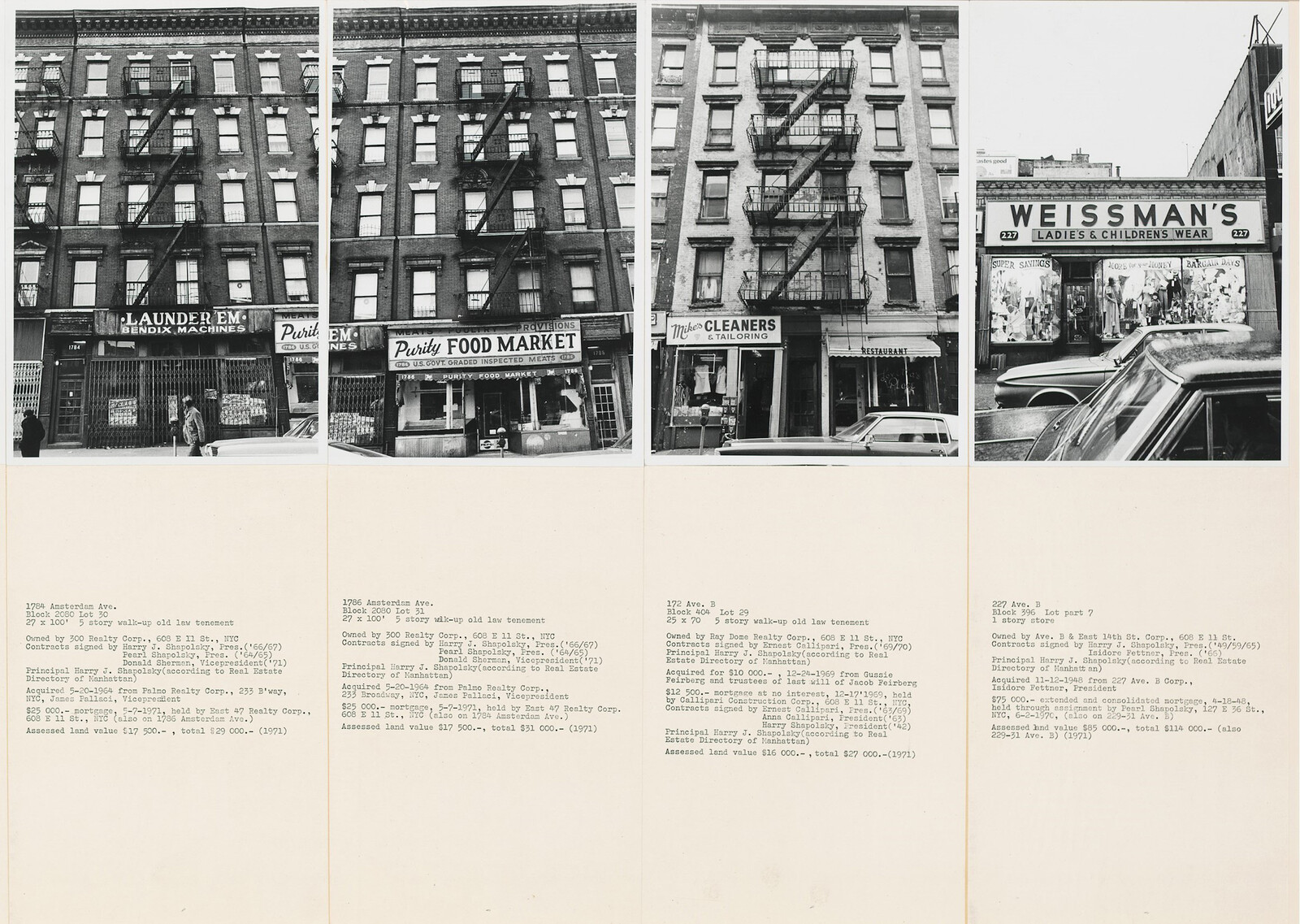

If you had never encountered Hans Haacke’s work before, then you might think, upon entering the first room of this exhibition: “Oh nice, look! How pretty and interesting. There are his op art-influenced canvases of the early 1960s, and the physical and organic systems (balloons floating, plants growing) of later in the decade.” In the next space, you might think: “Holy moly! Something must have happened around 1969/70, that guy really had a moment of political awakening—look how fiercely he’s attacking the powerful in the art world.” At which point a Haacke expert might pop up and tell you that of course there is a peculiar, logically imperative connection between those earlier experiments in form, system, and process and the later work that would become the paradigmatic form, system, and process of institutional critique. This expert would have a point. But the desire to always explain that connection as a logically inevitable and linear one is also a bit suspicious and needs to be probed—for which this retrospective (which travels to Belvedere, Vienna) is a welcome occasion.

The above thought experiment would not happen in actuality—before stepping foot in the first room, you have already encountered two later works—and so the …

January 17, 2025 – Feature

Value in, garbage out: on AI art and hegemony

R.H. Lossin

In 2023, Refik Anadol launched the digital artwork collection “Winds of Yawanawa.” In collaboration with the Yawanawa people of Brazil, Anadol collects data from the Brazilian rainforest and combines it with drawings by Yawanawa artists to create 1,000 AI-generated NFTs that can be purchased with Ethereum. This massive undertaking is intended to “protect the Amazonian rainforest” by “preserving and uplifting Indigenous modes and models of environmental protection and sustainability.” Anadol, who’s made a name for himself championing the use of artificial intelligence as a new “pigment,” has largely organized his practice around environmental crusades. In 2024, his AI-generated portrayal of coral reefs Large Nature Model: Coral—a work which, according to an official United Nations press release, “offers an unprecedented glimpse into the vastness and complexity of our oceans”—debuted at the UN as part of a sustainability initiative. In addition to centering the Yawanawa through data collection and transforming coral reefs into two-dimensional, undulating masses of color, Anadol is broadly engaged in using AI to represent our natural environment in a bid to reimagine and save not just coral reefs or tropical rainforests, but “the future.” What is going on?

“Hegemony,” wrote Raymond Williams, “is the continual making and remaking …

January 16, 2025 – Review

“Admired, collected, and put on display”

Kenny Fries

Many museum exhibitions—and re-hangings of permanent collections—have in recent years aimed to address legacies of colonialism, as well as outdated and oppressive gender and sexual “norms.” Sometimes these shows incorporate contemporary art in response to historical work now viewed as pejorative or oppressive. Too often forgotten in these re-visions of art/history is the stereotypically dehumanizing representation of disability and disabled persons. “Admired, collected, and put on display,” in the Baroque treasury of the Dresden Residenzschloss, attempts to rectify this glaring omission by employing the work of contemporary disabled artists to provide critical context to such royal collections, as well as to render more fully the history of disability representation.

This curatorial goal is crucial yet its enactment is problematic, often re-inscribing this dehumanizing history. Attempts are made to mobilize the contemporary art to demythologize disability, but the historical works and what they promulgate dominate contemporary pieces by Eric Beier Eva Jünger, Steven Solbrig, and Dirk Sorge, which are placed mostly outside the small exhibition room or, in the case of Beier’s work, used more as a structural crutch rather than integrated critique.

Floor guides provide access for visitors who are blind or have low vision. But in the spacious covered …

January 15, 2025 – Review

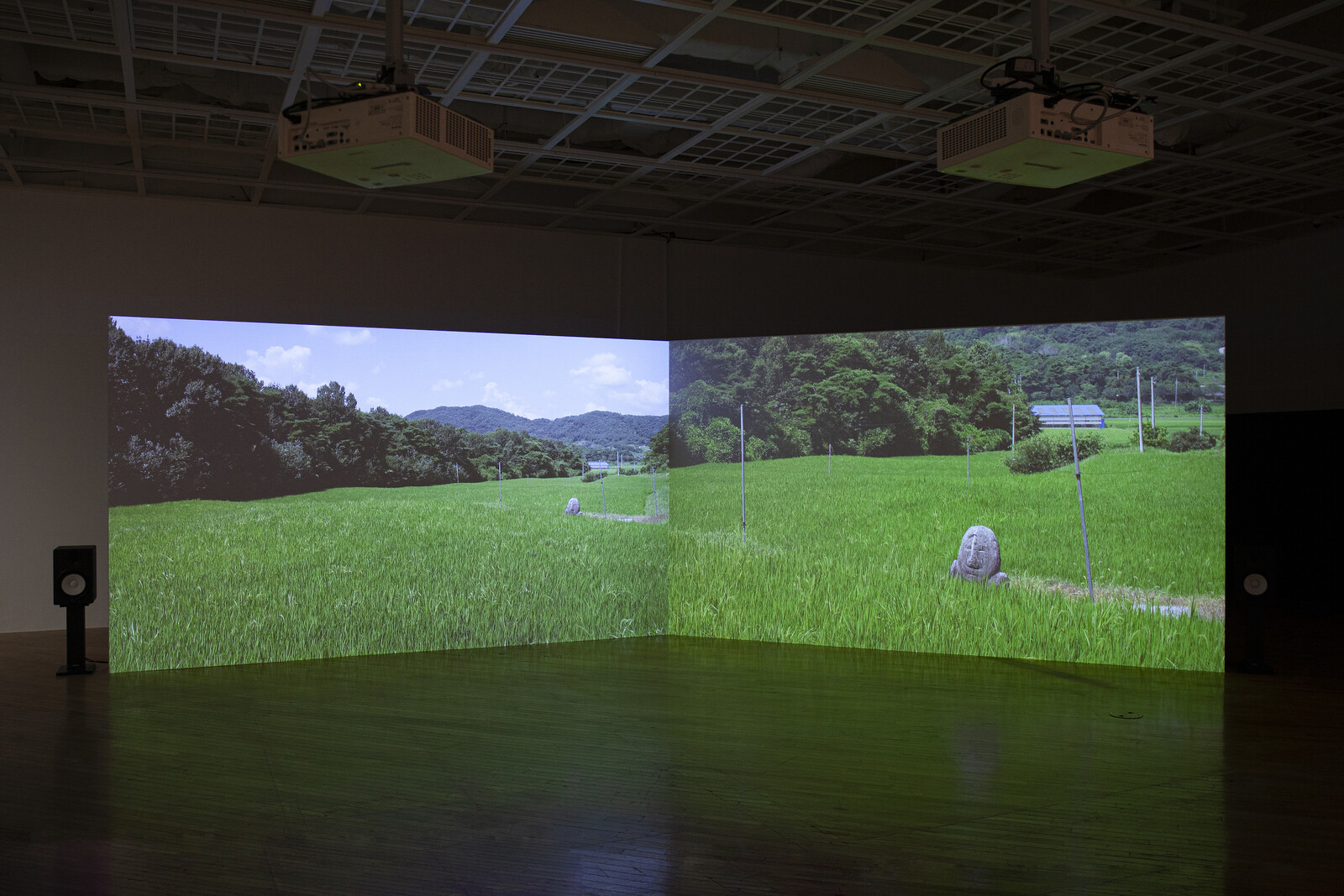

ikkibawiKrrr’s “Rocks Living in Rewind”

Hallie Ayres

Robert Hazen outlined the theory that the mineralogy of planets and moons evolves as a direct result of interactions with life. While only a dozen mineral species are known to have existed when our solar system formed 4.6 billion years ago, today Earth plays host to more than 4,400, an indication that the chemical and biological processes enacted by organisms engender their formation. On a planetary geology scale, then, our interactions with rocks stimulate their development as much as they buttress ours.

This molecular symbiosis threads through the works in ikkibawiKrrr’s solo exhibition at Art Sonje Center. Since 2021, the trio—composed of Cho Jieun, Ko Gyeol, and Kim Jungwon—has explored the interactive and shifting boundaries between humans and the nonhuman natural world. The collective’s name comprises “moss” and “rock” in Korean, plus the onomatopoeic sound “krrr.” While previous bodies of work have centered on seaweed, grass, and moss, “Rocks Living in Rewind” sees the group hewing to that more abrasive component of their appellation, through a sustained focus on the South Korean peninsula’s disregarded stone statues of Maitreya–the bodhisattva believed to embody the future Buddha.

Visitors are greeted by Buddha High Five (all works 2024), a cement hand, larger than …

January 10, 2025 – Review

Hamad Butt’s “Apprehensions”

Tom Denman

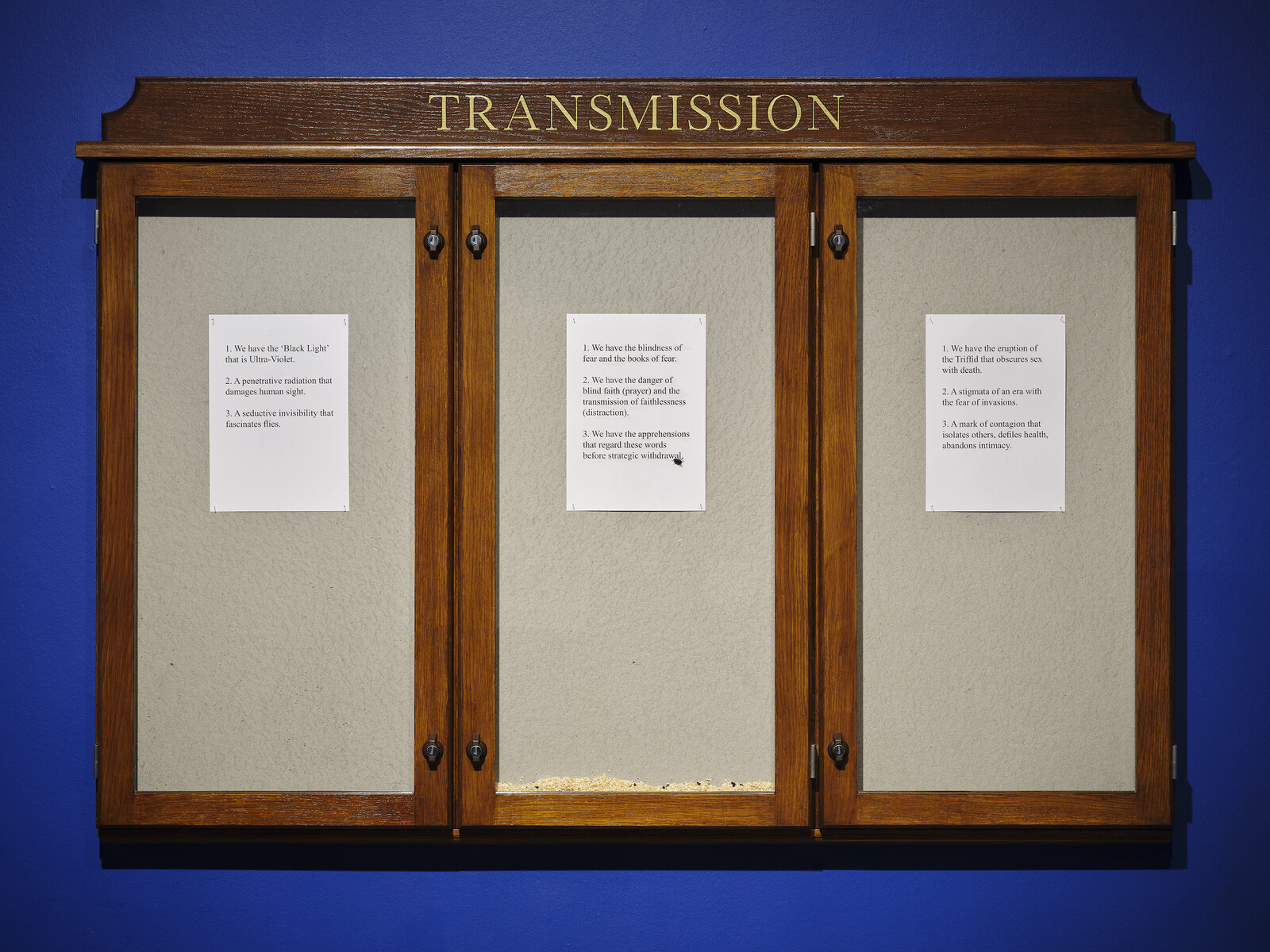

Hamad Butt’s long overdue first retrospective opens with what might as well be a statement of unfinished business. A noticeboard headered with the word “TRANSMISSION” houses behind its glass doors a colony of live flies; pinned to the board are three sheets of A4 paper printed with tercets canticulating blindness, fear, contagion, and the obscuration of sex with death. Transmission (1990)—a chilling installation revolving a prayer circle of glass books splayed on the floor on parabolic legs, with the pages resembling wings, and the potentially blinding ultraviolet lights acting as spines, or thoraxes—is Butt’s first concrete response to the AIDS crisis, spurred by his own HIV-positive diagnosis in 1987, the same year he enrolled, aged twenty-five, at Goldsmith’s College in London. It was the focus of his degree show in June 1990, a month before the former Goldsmith’s student Damien Hirst exhibited his raucously acclaimed, also fly-infested A Thousand Years (1990). Presumably interpreting Hirst’s piece as plagiarism, Butt revoked the flies from his own installation and the original noticeboard has long been lost. Although the wall text omits this controversy, the curators have honored the artist’s decision by showing the refabricated component separately, presenting the rest of the installation in …

January 9, 2025 – Review

Antonio Obá’s “Rituals of Care”

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie

In September 2019, an eight-year-old girl named Ágatha Vitória Sales Félix was shot and killed by police in Rio de Janeiro as she was riding home in a small public bus with her mother. The officers argued that they had been fired upon first, and moreover, that they were in the midst of a wider war, part of the former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s “30 bullets for every bandit” crackdown on crime, during which nearly a third of all violent deaths in Brazil’s second largest city came at the hands of the state. Witnesses countered that there had been no such shots, and rather, that the officers, unprovoked, had targeted an unarmed motorcyclist, and missed. Ágatha Félix was shot in the back and rushed to a local hospital, where she died. Reportedly, police then raided the hospital to try and retrieve the stray bullet that had killed her, lest it be used as evidence against them, but were unsuccessful. Within days, protests erupted across the favelas of Rio, where Ágatha was born and raised.

That same year, the artist Antonio Obá painted a harrowing group portrait of thirteen small boys crowded together behind a table piled …

January 8, 2025 – Review

“OTR^S MUND^S”

Gaby Cepeda

In 2020, the group exhibition “OTRXS MUNDXS” offered a snapshot of Mexico City’s young artists and collectives. Whereas that first show felt overly ambitious, occupying the whole of Museo Tamayo and adopting a theoretical framework that attempted to define a generation, the latest iteration goes in the opposite direction: abbreviated to a few galleries and the central patio, and lacking any coherent sense of structure. The memorable (and sizable) installations by individual artists that were a feature of the first show are here replaced by a more scattered approach that conceives of the museum as a musical instrument, to the detriment of the art displayed within it.

The exhibition begins in the central patio, where a MIDI-controlled pianola has been programmed to play Conlon Nancarrow’s Study No. 21 (1948–60)—the piece is notorious for its intense speed and posthuman notation—once every hour. On my visit, however, it wasn’t working. Two sculptural speakers nearby played a combination of music, sounds, and noise selected by three radio collectives: Radio Noche, Radio Nopal, and Radio Imaginario. Abraham González Pacheco’s Windborne Message (2024), a series of beige polyethylene curtains hanging at different heights and embroidered with fists, roses, and scribbles, offered a scenography of sorts. …

January 7, 2025 – Editorial

Years that ask and answer

The Editors

Art criticism operates with a time lag. If you accept that art is shaped by the historical contexts in which it is made, then the critic must always be writing after the fact: after all, it takes time for the artist to make the work, it takes time to organize the exhibition, and then it takes time to write the review of that exhibition. Even a work made expressly in response to a specific event might not come to be written about until weeks, months, or years have passed. By which time the world might have moved on, the calamity been forgotten, the government deposed, attitudes shifted.

Yet this might be the great advantage of the form. However frustrating it can be that criticism must trail behind the news, this means that it also resists the violently unstable model of history that a hyper-accelerated and functionally hysterical media cycle propounds. Criticism narrates an encounter with the past (whether near or distant) and with other perspectives. It depends on a belief in continuities and commonalities, which is to say a commitment to the principle that the past carries meaning in the present, and that every other person’s experience of the world …

December 23, 2024 – Review

“The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975–1998”

Serubiri Moses

Sheba Chhachhi’s photographs, taken on the frontline of the Indian women’s movement—crisp black-and-white images of working-class women at a demonstration, performing in a play about gender-based violence, and in their own homes—encapsulate this watershed exhibition well. “The Imaginary Institution of India”—which includes over 150 works of painting, sculpture, photography, and other media, sprawling over two floors and thirteen sections—is a show about class and its tensions, playing out violently in the world’s largest democracy. Curator Shanay Jhaveri’s thesis, though, rests on the formal and aesthetic shifts as shaped by the politics of this time period (1975–98). For Jhaveri, developments in landscape painting, for example, illustrate the ways in which class tensions came to a head after the declaration of Emergency in 1975.