One surprising legacy of the United States’ public diplomacy across Southeast Asia during the Cold War is an eighteen-minute film featuring dialect and music indigenous to Thailand’s northeast region. Produced by the United States Information Service (USIS), The Community Development Worker (1963) pairs black-and-white 16mm footage of the smartly dressed titular subject touring a dusty village on foot to a soundtrack of jaunty, laudatory songs.1 Scenes of him offering guidance to beaming villagers segue into footage of lectures, laborers digging sunbaked fields, and provincial officers orchestrating the rebuilding of a school. Meanwhile, the lyrics of the accompanying mor lam—a propulsive form of sung storytelling accompanied by a khaen (bamboo mouth organ)—beseech the people of Isaan, as this region is known, to not be lazy, and to work together to improve their community rather than wait for government.

This melodious attempt to ward off communism in Isaan demonstrates how the United States’ Cold War propagandizing included the co-opting of vernacular forms and local voices, as well as the invocation of rural stereotypes and center-periphery dynamics.2 Yet in the hands of Ukrit Sa-nguanhai—one of four artists contributing to this group exhibition at the Thai Film Archive on Bangkok’s outskirts—its local resonances are revivified, and extended, via appropriation.

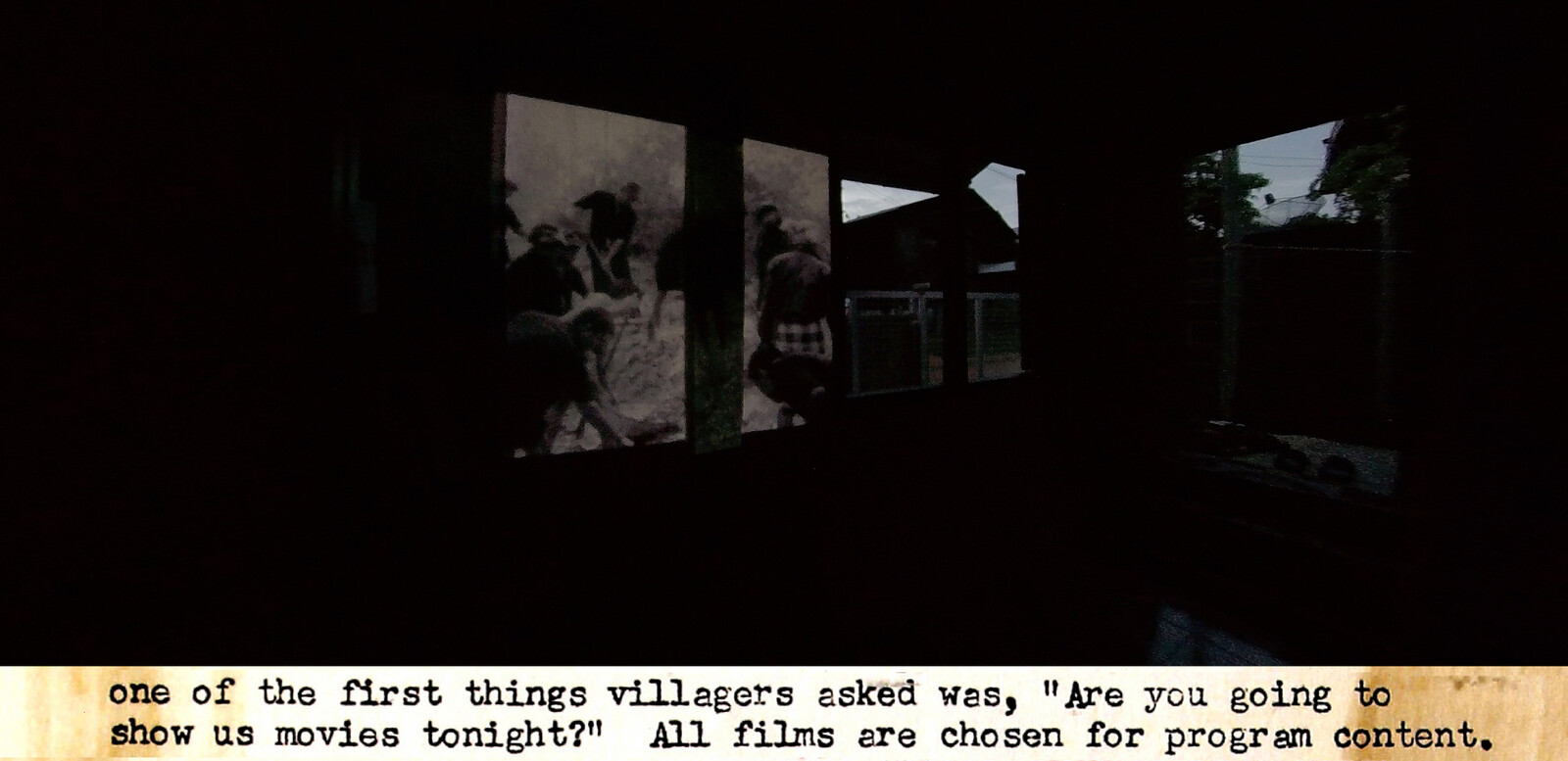

Playing on a large screen near the entrance is Trip After (2022), an oneiric travel vlog in which excerpts from this USIS film appear as a picture within the picture, and flicker against the interior walls of homes and sheds located in the rural areas where the film was originally shot and screened. These scenes are juxtaposed with long takes of quotidian life in these villages today—kids playing soccer, a man peddling into the distance, and so on—each joined by a narration derived from USIS field trip reports written in 1963 and ’64. Here, sober accounts of villagers’ enthusiastic reaction to the outdoor screening of USIS propaganda films over sixty years ago sit somewhat awkwardly with the modern-day documentary images. The net result is a nagging suspicion that today’s citizenry is out of step with, or inured to, the ministrations and rallying cries of assimilationist officialdom. And that, deep down, the cheerful villagers of Isaan always were.

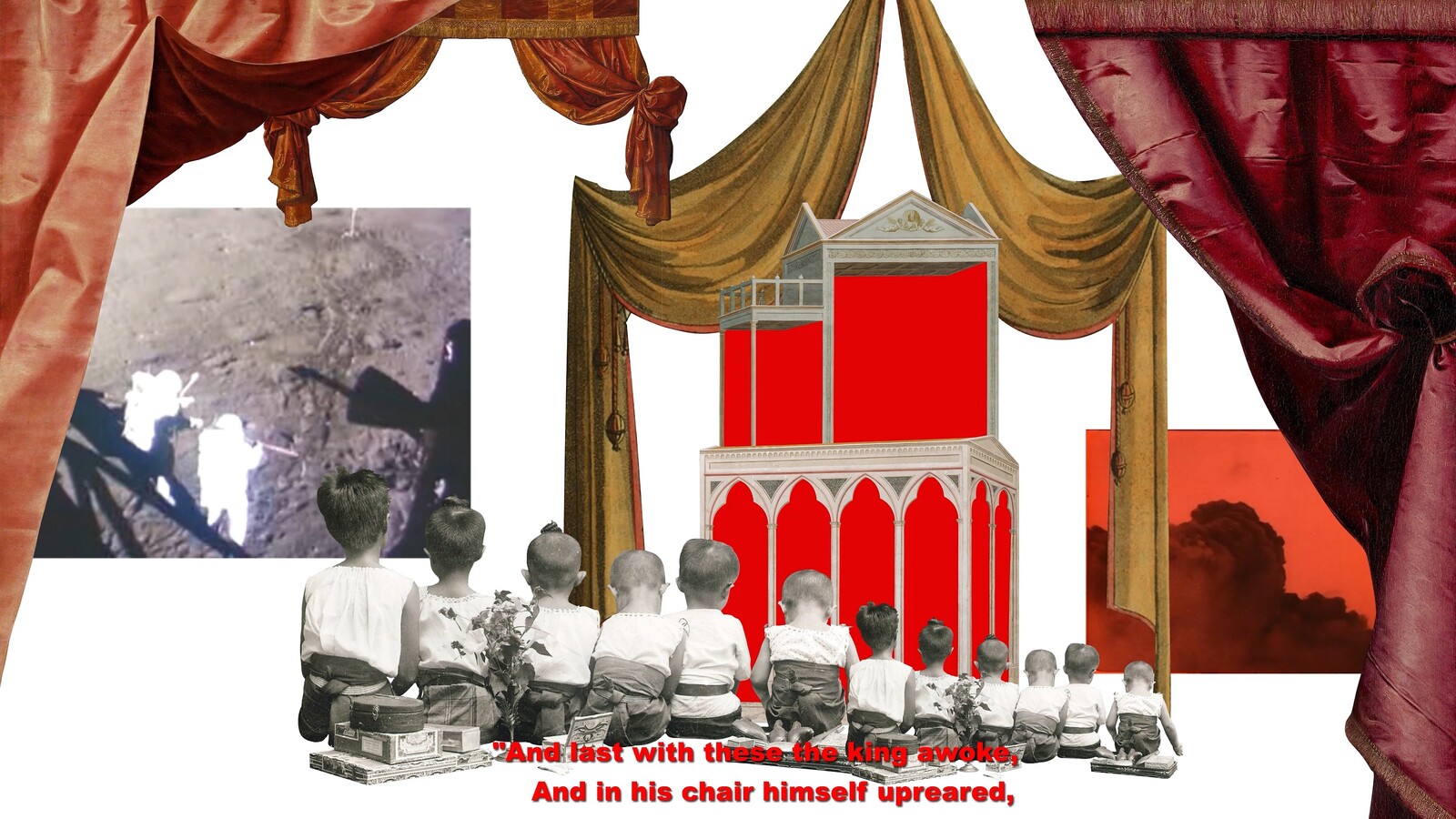

Trip After is the outcome of research into a shadowy tradition of itinerant outdoor film screenings in Thailand during the Cold War.3 More broadly, it illustrates this group exhibition’s overarching subjects: the sociohistorical breadth of film archive sources in Thailand, and the sociocritical potency of practices that tap them. In Nakrob Moonmanas’s kinetic counter-history (All the poetry and the pity of the scene, 2023), for example, cut-out engravings, murals, and photos pertaining to the country’s ruling Chakri dynasty and its mid-nineteenth-century royal court flash and fly across a white screen, alongside elements grafted from European paintings and frescoes. These rapidly shifting, and often droll, evocations of western-inspired modernization and auto-colonization under King Mongkut are joined by windows of old footage of royal ceremonies and events, sourced from the Thai Film Archive.

On the wall opposite, Chulayarnnon Siriphol’s Red Eagle Sangmorakot: Lessons from the Archive (2025) draws on Chao Insee (1968), a movie from a pulp 1960s action-adventure series. Siriphol has spliced fight scenes from a damaged 16mm print of this movie, in which a masked hero played by legendary actor Mitr Chaibancha trades punches with a baddie, with archive footage of boxers and scenes of himself training at a Thai boxing school. And behind a curtain nearby, Taiki Sakpisit’s fourteen-minute The Age of Anxiety (2013) turns scenes from 1980s fantasy movies into a screeching, strobing nightmare. Actors dressed in the rags or regalia of Thai folktales are frozen, mutilated, and jolted to a hellish cacophony of staticky noise.

Through poetics of dissent—some more bellicose than others—these works dredge up dark or excluded histories implicating the Thai nation-state. Moonmanas’s dynamic collages are joined by a voiceover, in which lines from Anna Leonowens’s The English Governess at the Siamese Court (1870) alternate with those from a memoir by a woman imprisoned in 2015 for appearing in a play about a fictional kingdom (her crime: insulting the monarchy). Siriphol’s work draws on a film series that tapped into the paranoia (and color palette) of Thailand’s Red Scare, while Sakpisit’s distressing audiovisual montage, made in the wake of the 2010 military crackdown, simulates one of its spiraling, periodic descents into collective madness.

Intriguingly, this show raises questions about the politics of media archives, too, not just those artists drawing on them. The Thai Film Archive came into being in 1984, after the discovery of early films of resplendent royals on tour, but has since blossomed into a more panoramic public organization (due in large part to a policy of collecting all films related to Thailand). Monitors strewn amid the video works provide ample proof of this: newsreels, sporting events, 8mm home movies, and tense interviews with reformed communists loop alongside early twentieth-century documentaries about royal ceremonies, government affairs, and tourism. Taken as a whole, this disorderly pageant of footage evokes an unstable body politic home to a cacophony of competing, disputatious voices. Intentionally or not, it also mirrors these artists’ interest in decentering and remaking national memory, rather than merely preserving it.

See: “พัฒนากร,” Film Archive Thailand (หอภาพยนตร์) (December 18, 2016), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-wV9PEtxe4s.

President Eisenhower, who established the United States Information Agency (the USIS’s domestic branch), succinctly articulated this modus operandi: “Avowedly propagandistic materials from the United States might convince few, but the same viewpoints presented by the seemingly independent voices would be more persuasive.” Kenneth Osgood, Total Cold War: Eisenhower’s Secret Propaganda Battle at Home and Abroad (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas: 2006), 77.

This tradition has preoccupied Thai moving image artists and film theorists alike in recent years. See May Adadol Ingawanij, “Itinerant Cinematic Practices In and Around Thailand during the Cold War,” Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, vol. 2, no. 1 (March 2018): 9–41.