Ed Atkins’s survey show at Tate Britain was initially going to be called “Loss” but opened with only the artist’s name above the door. Perhaps “Loss” didn’t scream summer blockbuster? Regardless, the decision to scrap this working title, mentioned without explanation in the catalog, seems significant. Gathering around sixty works from the last fifteen years, the exhibition charts a turn in Atkins’s practice from experimentation with digital technology as a metaphor for loss—alienation, emptiness, death—toward a more expansive engagement with art as a tool for personal expression, social connection, even redemption.

In the early 2010s Atkins established an international reputation with CGI films of lonely, weather-beaten men delivering strange soliloquies voiced by the artist. On display at Tate, Hisser (2015) presents one such figure wandering round his bedroom, his face covered in computer-generated wrinkles and purple sores. He masturbates in the corner before lying down and singing “didn’t know that life was so sad I cry.” The film is full of formal quirks: at one point the whole room slides down the screen to reveal a series of identical spaces like frames in a reel. Suddenly the specific details of this private interior, of intimate experience, appear formulaic and endlessly replaceable.

Then furniture starts to shake and—in a dramatization of a 2013 news story about a freak event in Florida—the room collapses, including the man tucked up in bed, into a sinkhole below. As the chasm opens it is viewed from above, so its depths become indistinguishable from the flat surface of the now blank screen. An equivalence is drawn between the digital image—easily manipulated, duplicated, obliterated—and the fragility of the protagonist’s life. Atkins features in his early films behind layers of dissimulation and irony: his words like obscure quotations, his melodies too cloying to be sincere, his body replaced by stock characters. The self emerges as a stacking doll, all opaque surfaces and empty hollows.

In the last five or so years, Atkins has been shedding these mediating layers, trading his nihilism for a more confessional mode. The exhibition is dotted with delicate self-portraits in red pencil and gouache paintings of the artist’s crinkled bedsheets. In one room there are hundreds of Post-it-note doodles he started making during Covid-19 to put in his daughter’s lunchbox: funny Guston-esque cartoons and messages like “I love you SO much.” He soon began uploading the drawings to Instagram and set up a website allowing people to sign up and receive them by daily email. They are, he insists in the catalog, “a great joy in my life, my real life as I currently live it.” “The excuse for their production is unquestionable,” he continues, “founded as it is in love.”

To extend this biographical interpretation, the shift in Atkins’s practice is explained to some degree by the fact that he was mourning the death of his father when he began filmmaking but now lives with a young family of his own. Beyond this anecdotal cul-de-sac, though, it is symptomatic of what Anna Kornbluh calls “immediacy style”—the current dominance of artistic forms that prize instantaneous self-expression and unmediated presence over critical reflection, partly to meet the demands of internet culture.1 This is epitomized by the Post-its, in their combination of familial intimacy and online distribution. Instead of narrative structure, conceptual proposition, or aesthetic challenge, they offer a feeling of access into the artist’s daily existence and the free flow of his imagination.

The expected response to this oversharing-as-art is suggested by a new live-action film in which actor Toby Jones reads the diary Atkins’s father wrote about his struggle with cancer to “an invited audience of young people.” For ninety minutes, they hang on his every word: laughing, frowning, crying. Nurses Come and Go, But None For Me (2025) exemplifies Atkins’s recent register. Although its subjects include illness and death, it is primarily about finding validation and togetherness through self-exposure. Limited to the first-person, it envisions a vacuous kind of connection without dialogue, a positive feedback loop of emotional detail and attentive smiles.

“Unquestionable” as Atkins’s love for his family may be, in isolation his increasingly explicit emphasis on personal experience is solipsistic and conservative. What makes the exhibition compelling nevertheless is that examples of this confessional approach often appear alongside remnants of his earlier negativity. Renaissance-style self-portraits hang close to undead virtual avatars; earnest first-person captions sit near opaque Wikipedia entries assembled by the anonymous blog “Contemporary Art Writing Daily”; and the Post-its share a room with Refuse.exe (2019), a computer simulation of hundreds of objects—skulls, bricks, furniture—falling through the air and crashing onto the floor. At every turn markers of authenticity and human contact are confronted with their opposites, the singularity of Atkins’s authorial voice is called into question, and the conventional chronology of a mid-career retrospective is disturbed. Traditional notions of selfhood are set in opposition to the entropic force of the digital.

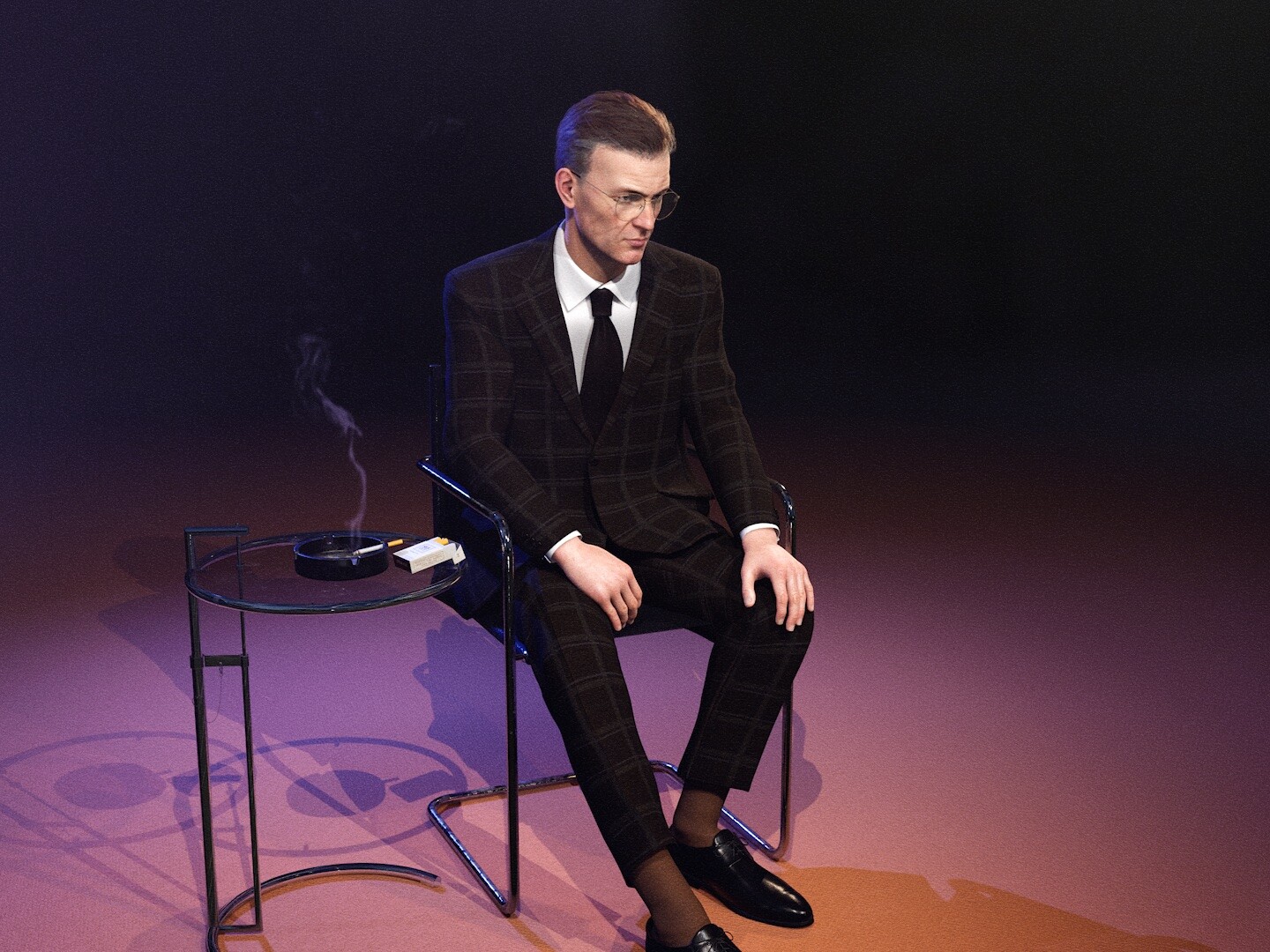

The most stimulating works hold this tension within themselves. The Worm (2021), for instance, takes its audio from a phone call between Atkins and his mother in which she describes her difficult childhood and insecurities about being “chubby.” Onscreen, meanwhile, a generic CGI man sits in a dark room wearing a crisp suit, his movements determined by motion sensor data taken from Atkins’s body during the call. When the artist laughs at an anecdote, his avatar looks malevolent with a mechanical grin; when he hums in sympathy, his double stares blankly into space.

The awkward relation between cold image and warm audio mirrors the absurdity of the audience’s consumption of a stranger’s most vulnerable thoughts in the gallery. The disjointed animation impedes access to the “real” space of the phone call, maintaining a distance between public and private, representation and direct experience, against the expectations of our immediacy culture. Crucially, the critique also works the other way: the conversation between mother and son, with its themes of honest communication and intergenerational reckoning, brings into stark focus the shallowness of the digital image and the desolation of the suited figure. Held at a remove, struggling against such visions of emptiness and loss, love becomes not a sentimental spectacle but a critical force. Rather than immersing viewers in a numbing simulation of authentic life, the film provokes in us the same desire that seems to have driven Atkins in recent years, to move away from the groundlessness of cyberspace toward sincerity and hope.

See Anna Kornbluh, Immediacy, or, The Style of Too Late Capitalism (London: Verso, 2023).