Gabriel Orozco’s first museum show in Mexico for almost twenty years seeks to answer a fundamental question: How does his practice work? As its title suggests, this career-spanning survey is heavily invested in the fact that Orozco operates across numerous media. “Politécnico Nacional” is the name of a prestigious public school in Mexico City and also, at least ostensibly, what Orozco currently identifies as: a poly (as in many) technic (as in media), national artist. It is, of course, this “national” part that has caused some aggravation among local critics. Orozco is the international artist of his generation, the prodigal son who refuted his Mexican-ness in his voyages on the global circuit, and at last returns to the national bosom—and embraces the state, no less.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. The show stratifies the museum’s four floors into elemental chapters: “Air,” “Earth,” “Water,” and “Compost.” It makes for a smart exhibition, especially the opening gallery. This first space is packed with objects, but precise curating means that it still feels fittingly airy. Right off the bat is a classic: Crazy Tourist (1991), the famed photograph of oranges sitting on ramshackle wooden tables somewhere in Brazil. I stopped to wonder why this image of his, along with Pinched Ball (1993), Sleeping Dog (1990), and Cats and Watermelons (1992), felt like such a revelation when I first saw it online as a teen. These works still hold me today, and I was delighted to encounter them in person in their neat beige frames.

More examples of career-defining pieces abound, pieces viewers came to love (or hate) thanks to their succinct, one-liner quality: La DS (Cornaline) (2013), the red version of his slimmed-down Citröen, is shown next to Carambole with Pendulum (1996), his oval billiards table without pockets. A highlight is the installation Toilet Ventilators (1997/2000): six fans that spin far up in the high-ceilinged space, swirling delicate streams of toilet paper like mechanical artistic gymnasts. Another favorite is the minimal gesture of Untitled (Yokohama) (2001), a visibly used piece of luggage casually positioned next to the worst piece in the show and (perhaps not coincidentally) among the most recent. Ánima / Anima (2023–24) is a monochromate tempera painting overlapping da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (ca. 1490) with Coatlicue, the Mexica deity—exhibited at his solo at kurimanzutto last year. Orozco, whose father Mario Orozco Rivera was a muralist and assistant to David Alfaro Siqueiros, was a painter for a short stretch in his youth, and his unexpected return to the medium is marred by tedious references to national culture and less-than-great technique.

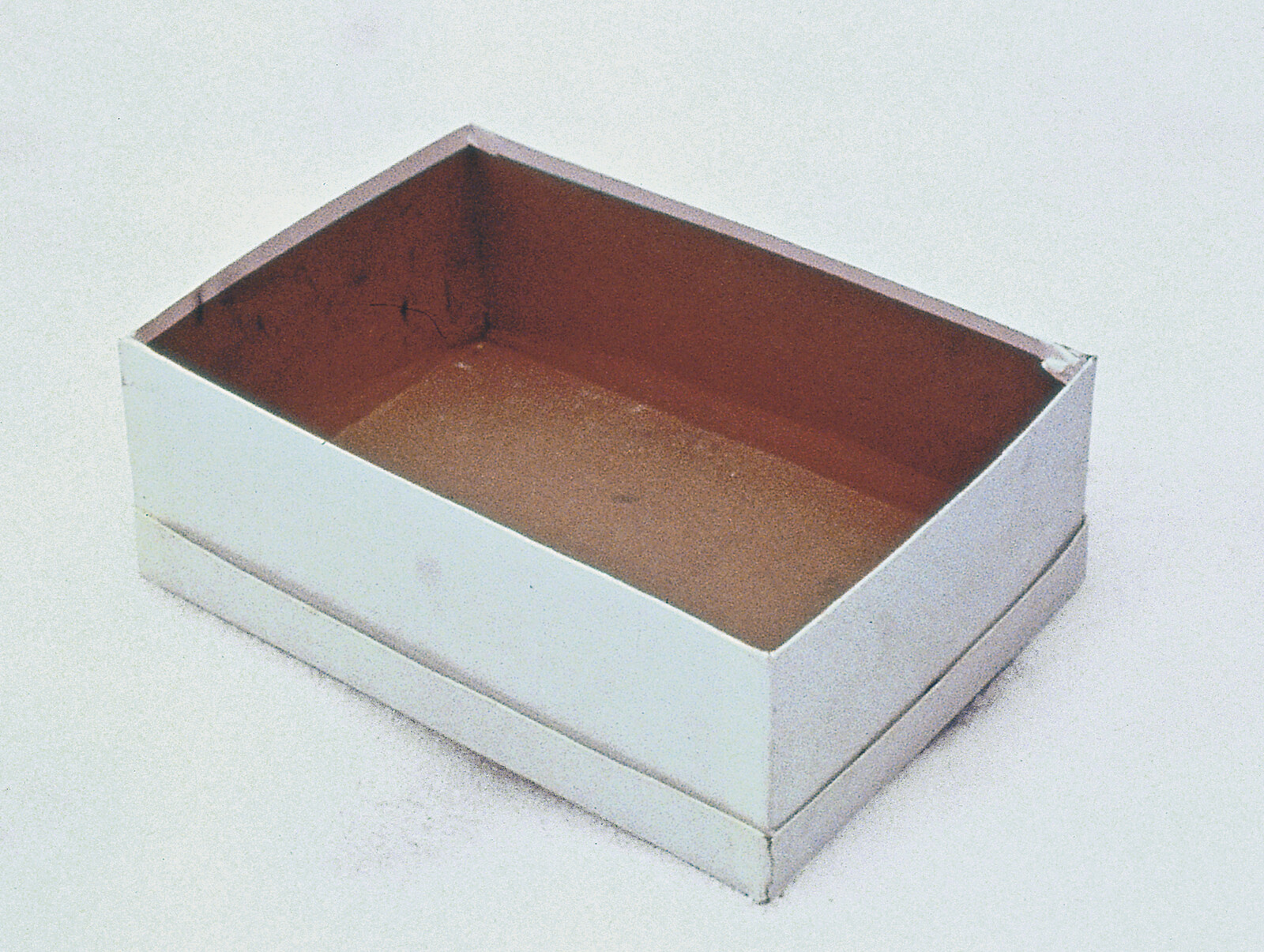

The second gallery, “Earth: Ground,” starts strong. One of Orozco’s major hits rests on the floor: the Empty Shoe Box (1993) shown at that year’s Venice Biennale. Here his gambit-prone, playfully transgressive spirit feels alive, sitting right across from “First was the Spitting I-IV,” made that same year, a series of alluring drawings made with toothpaste spit and tiny circles baroquely sprouting from its dried stains. A group of yellowing, polyurethane foam sculptures (Spume 3 & 6, 2003) hangs overhead, their naturalistic forms gracefully evoking flying fish from a nasty chemical material. They float near an array of forgettable recent paintings, and many other inconsequential pieces grouped together with no apparent relation: a map of Chapultepec next to some papier mâché sculpture of socks (Socks, 1995) and an onion peel sitting on a plasticine glob (Onion Crown, 1994).

Indeed, something about the concentration of objects in this room plays against the most exciting ones: My Hands Are My Heart (1991), the well-known diptych of two hands pressing clay—including the heart-shaped form (Model [My Hands Are My Heart] Version 2, 1991), resting among a larger group of anatomically inspired pieces—and the lovely and gross “Lintels” (2001/24), a series of raggedy gray sheets hanging from tensed lines and pressed from lint collected from clothes dryers. Displayed here in the company of numerous less-impressive pieces, these successes feel serendipitous rather than considered—like, we get it, Orozco is playful. But the exercise is almost too revealing, suggesting a lack of intentionality. The feel is of an artist throwing stuff at the wall to see what sticks—spit, probably.

The third gallery, “Water: Aquarium” houses the impressive pseudo-fossil Dark Wave (2006), a resin cast of a whale skeleton painstakingly decorated with concentric circles drawn with graphite. It hangs in the glass-walled space as if in captivity (much like its sibling at the Biblioteca Vasconcelos), surrounded by a terrace on which Four Bicycles (There Is Always One Direction) (1994) is presented. An archetypically Orozcoesque piece, its eight bicycle wheels include some of his favorite themes: circles, rotation, sports, and perhaps above all his embrace of nomadic internationalism. Crucial to the early success of pithy formal experiments such as this is their legibility to global audiences. Viewers do not need to know that the piece takes inspiration from Rotterdam, the bike-friendly city in which it was made, to appreciate its witty and surrealistic qualities.

The exhibition wall texts resist the urge to over-explain the work until the basement, “Compost,” in which six additional texts elucidate Orozco’s signature themes: public domain, polytechnics, circular games, the market’s gambit, and fieldwork. The texts are often written in a lofty style, as they tend to be in celebratory retrospectives. Some point out the obvious, while others add to a creeping sense of tautology (“Earth: Soil,” “Water: Aquarium,” etc.) and raise the question of how often Orozco repeats himself. Indeed, in this section, the fixation on familiar themes congeals into risk-aversion.

Perhaps this reflects a particular moment in Orozco’s career, when the investment of national and commercial institutions in his success have made him too big to fail. The feeling of an artist surrounded by safety nets that forego the possibility of failure is related to his semi-official status as a “Great Mexican Artist,” commissioned in 2019 by former president Andrés Manuel López Obrador to design a new master plan for Chapultepec Forest. By the end of this consecrating retrospective, the risk that once defined Orozco’s work, and the love of the game celebrated in the exhibition texts, appears to have been lost. A TikTok-format video in the bottom floor reminds us that Orozco was once the most polemic, relevant artist in and from the country. Today, like many of his predecessors, he seeks refuge in the incumbent government’s nationalist vision for culture.