For the layperson, ikebana, a traditional Japanese technique of flower arrangement, strikes a mysterious balance between chaos and order, atemporality and contingency, structure and uncertainty. A floral interpretation of the harmonic principles of cosmic order particular to the national culture, ikebana can seem inscrutable to any viewer unfamiliar with its traditions.

Ikebana arrangements are also typically presented in religious, domestic, and private spaces, and so an exhibition devoted to the form in a contemporary art venue such as the Kunstverein München is unusual. They are also accompanied by aesthetic expectations and conventions. When it comes to the representation of flowers, no one wants ikebana to bear the same existential weight as a Flemish still life or Van Gogh’s fat sunflowers and trembling irises, all crammed into a terracotta jar. Even those with a lay understanding of the practice can recognize that asymmetry, sobriety, containment, and a careful, choreographic construction of negative space are key to ikebana, and that these values—and their underlying codes—are very different to those by which the western still life tradition is judged.

Indeed, the practice of ikebana contributed to the ultranationalistic imaginary of Japan, reaching its greatest popularity during the 1920s and ’30s.1 Reinforcing protocols and traditions, it is described by Shoso Shimbo as a “nationalistic art, kokusui geijutsu, and a spiritual training, seishin shuyo” helping to “encourage a spirit of endurance that would overcome hardship and lead the nation to victory” during World War II.2 In parallel to this ambitious patriotic mission, the different and quite radical school emerged. Inspired by the spirit of accessibility, the minimalist aesthetics, and the functionalism of western Modernism, “freestyle ikebana” also challenged classical ikebana’s reliance on “noble” plants. One of its leading exponents, Kosen Ohtsubo, moved the form beyond the botanical realm, expanding a domestic scale towards the context of public art and putting it in dialogue with sculpture and performance.

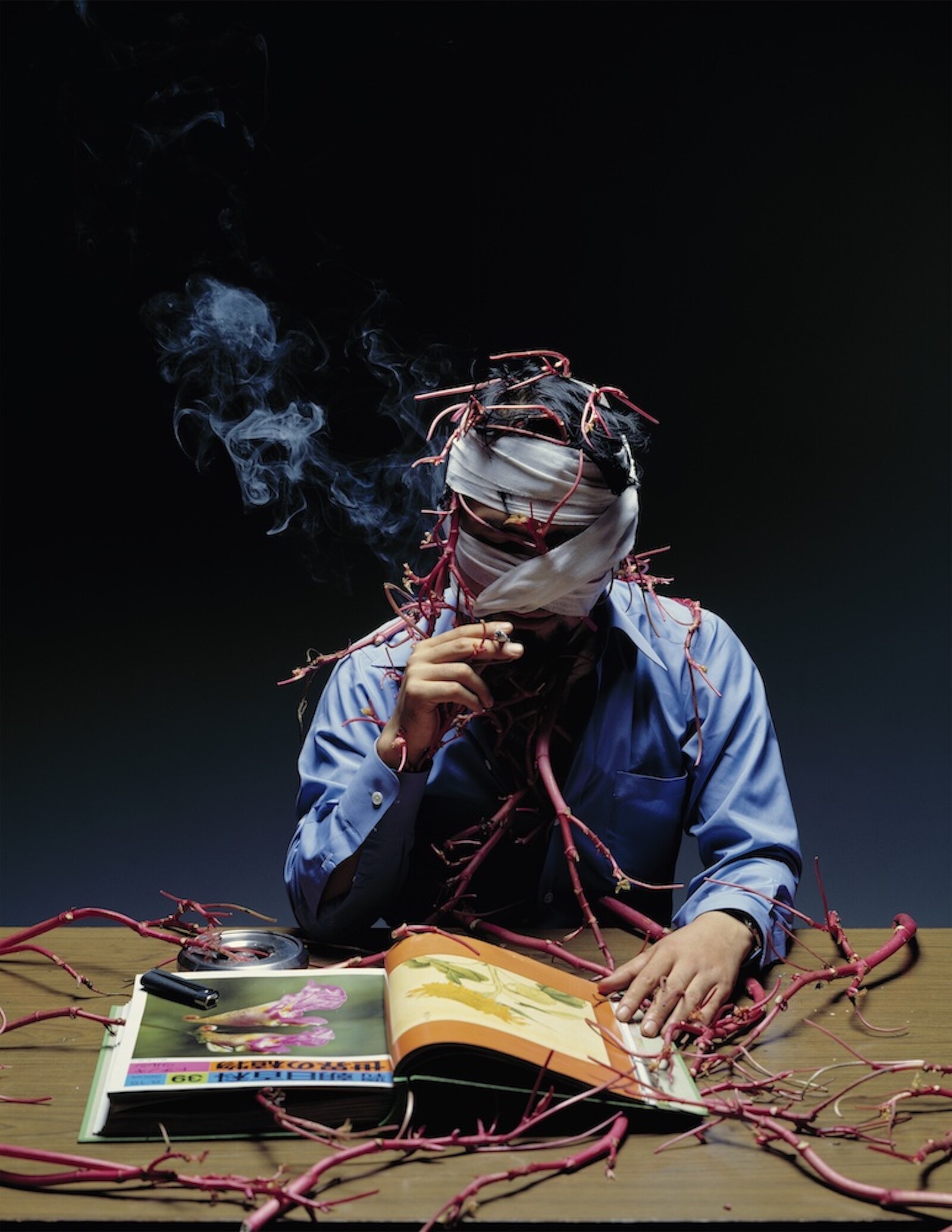

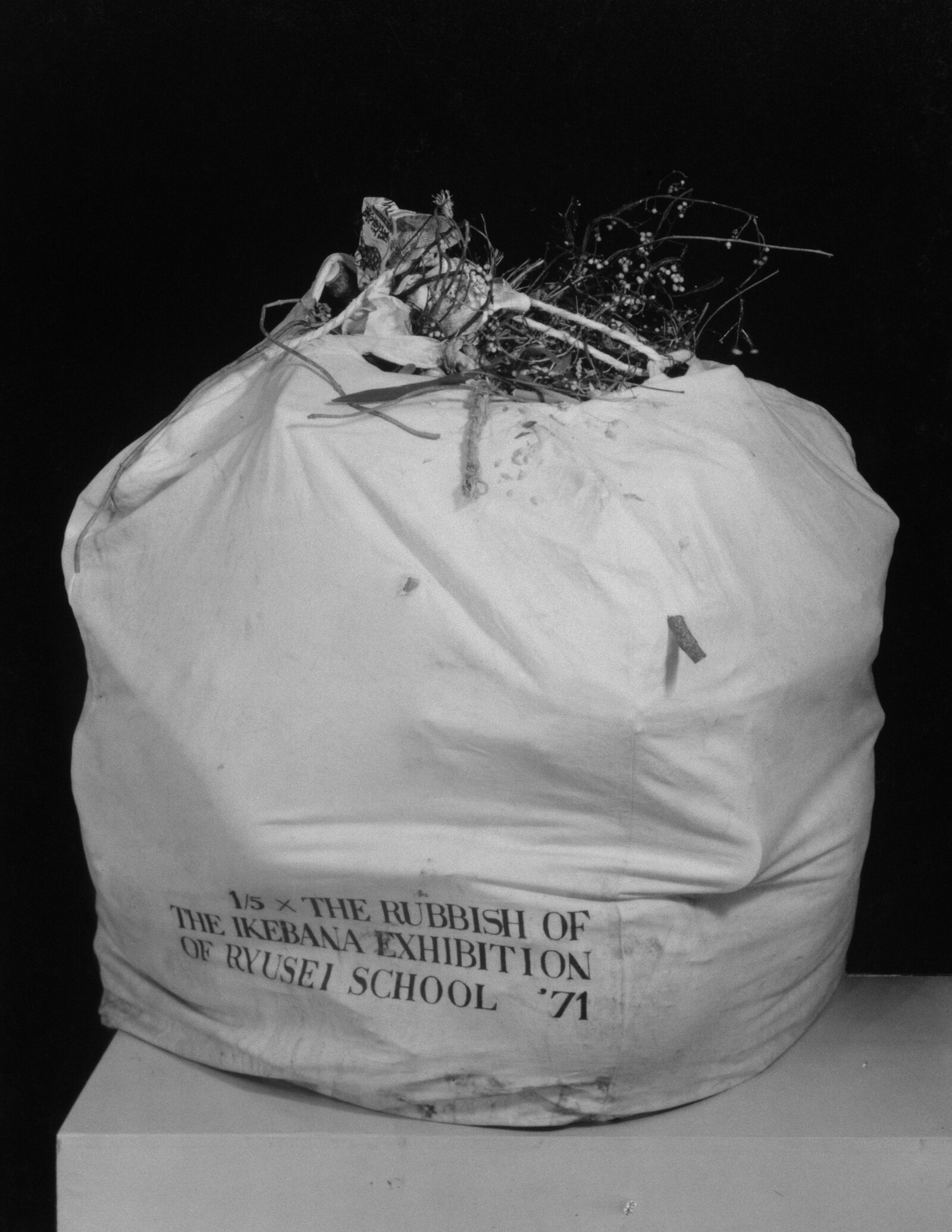

Ohtsubo studied under Kasen Yoshimura at the Ryūsei-ha Ikebana School, and his teacher’s inclusion of vegetables and non-organic materials such as metal and plastic had a strong impact on his work. The artist has since become a cult figure for those interested in more-than-western contributions to histories of performance, Minimalism, and Arte Povera, and in art’s continued engagement with what is left of “nature” in the Anthropocene. In Munich, photographs documenting his long career and radical creations include an image of Ohtsubo in a bathtub covered with flowers and leaves, smiling at the camera (I Am Taking a Bath Like This, 1984); of an aloe vera branch surrounded by crunched ping pong balls in a wooden box (Like an Umbilical Cord, 1974); a portrait of the artist smoking while wrapped in white bandages and long castor bean plants (Botanical Man, 1978); and of a large bag filled with the leftovers of an ikebana show (⅕ the Rubbish of the Ryusei Exhibition, 1971).

In 2013, artist Christian Kōun Alborz Oldham came across Ohtsubo’s work and started training under his guidance, a process that culminated in this exhibition, which celebrates their collaboration and friendship. Both artists present their own ikebana creations, each of which reverberate with the other’s forms, movements, and spatial arrangements. Ohtsubo’s Willow Rain (2025) is an environment made of 800 basket willow branches suspended from the ceiling. It creates a portal composed of thin, long strips of dried plants that, inverting the natural order of vegetal growth up from the ground, invites viewers to look upwards, both to the suspended plants and to the hypnotizing shadows they cast upon the walls. In the surrounding spaces, Oldham’s Dateline (2025) consists of Medjool dates strung on lightning rods, merging minimalist aesthetics with reference to a staple Middle Eastern food. By creating curvy, wavy lines that emerge from the walls and force viewers to circulate around them, Dateline establishes a counterpoint to the vertical movement of the Willow Rain and choreographs visitors’ movement across the space.

The show’s central work is Ohtsubo’s Linga München (2025), made of 300 basket willow branches arranged in a circle more than two meters in diameter, with thousands of flowers and leaves scattered within and around it. It is very tempting to touch it, to rearrange the buds that lie on the ground, to enter its hollow center; it smells of spring meadows and florists. The branches’ arrangement resembles a bird’s nest in its remarkable balance between disorder and skillfulness. Calling this ikebana feels awkward—as if Simone Forti’s Huddle (1961) and Mario Merz’s igloos could be ikebanas too—but also liberating and transformative. It allows ikebana into the history of art, rather than treating it as an art with its own hermetic traditions. The practice thus becomes a method of questioning nature-culture divisions, and much more than a highly coded grammar only for initiates.

See Osamu Inoue, The Thoughts of ikebana (Kado no shiso) (Kyoto: Shibunkaku, 2016).

Shoso Shimbo, “Nature in Ikebana (Japanese Flower Arrangement): The Freestyle Ikebana Movement in the 1920’s and 1930’s, and Its Effect on Avant-Garde Ikebana After the War,” The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2020, Official Conference Proceedings: 3, https://papers.iafor.org/wp-content/uploads/papers/acah2020/ACAH2020_55872.pdf.