How do we move beyond histories that no longer fully represent us? The 2016 peace agreement with the FARC, which brought to an end roughly fifty years of war between the Colombian government and left-wing militia groups, stipulated three monuments to be built from the militias’ surrendered weapons and munitions. Doris Salcedo’s commemorative monument in Bogotá—a commission from the Colombian Ministry of Culture—inverted and expanded the idea of heroism usually accorded to monuments. She designed a cast iron floor made from thirty-seven tons of melted-down weapons that were cast in molds hammered into shape by women victims of sexual violence by guerrillas during the conflict.

This anti-monument was installed in a new cultural center—Fragmentos Espacio de Arte y Memoria—in the retrofitted ruins of a house from 1565 in Bogotá’s La Candelaria neighborhood. The center follows the example of local leaders, including former Bogotá mayor and social practice artist Antanas Mockus, in its aim: to fuse art and policy and bring publics together to process the trauma of decades of war. At Fragmentos, curator Carolina Cerón gathers pieces by five Colombian artists—Mónica Restrepo, Ana María Montenegro, María Leguizamo, David Medina, and María Isabel Arango—whose work “bridges past and present.” The show poses the question of what to do with sociopolitical and cultural memory of years of armed conflict and an imperfect peace process, set against the resolutely violent backdrop of Salcedo’s monument.

“La madre, las palabras con los nombres, un sorbo y cuatro rayos” [The mother, the words with the names, a sip and four rays] is the result of the first open call by Fragmentos, which aimed to offer local curators the opportunity to gain experience and to highlight the work of emerging Colombian artists. With the war and its cost (human, societal, political) forming the literal ground on which the show stands, the project makes the institution available for a new generation of artists and curators to parse histories that no one these days wants to talk about, but that also remain impossible not to talk about. This is the problem with memory: forgetting and remembering are part of the same process, of retelling and reshaping the past as present realities and prevailing values shift.

Entering from the street, visitors encounter the long hallway of the building lined with piles of tumbled, sun-bleached driftwood, which form a meandering riverscape. This is Sorbo [Sip (2024) by María Leguizamo. The waist-high piles are meant to resemble a river shoreline, and also suggest volumes of bones of the missing disappeared into the river. A gentle hum subtly prompts visitors to touch the wood and feel its vibrations, as though the river’s bones tell a story we can only understand through bodily perception. Leguizamo acknowledges how experience, violent or otherwise, changes people and societies, in much the same way as these logs were changed by tumbling in the Magdalena river, from which they were collected.

Riffing on a similar idea, in a small gallery to the right, Ana María Montenegro’s La Claridad (2024) is a two-channel video installation recounting the experiences of Alex, a Colombian army conscript who was struck by lightning four times and miraculously survived all four strikes. Alex and his aunt emphasize how, according to local healers, being struck by lightning changes a person. If the electricity is not sufficiently discharged into the earth, lightning will continue to seek them. The video narrates Alex’s experience surviving the lightning strikes, but also examines the medical and local healing treatments, the social stigma, and the legal restitution process he went through, metaphorically alluding to the shock of war, displacement, and abandonment that communities across Colombia experienced between roughly 1958 and 2016.

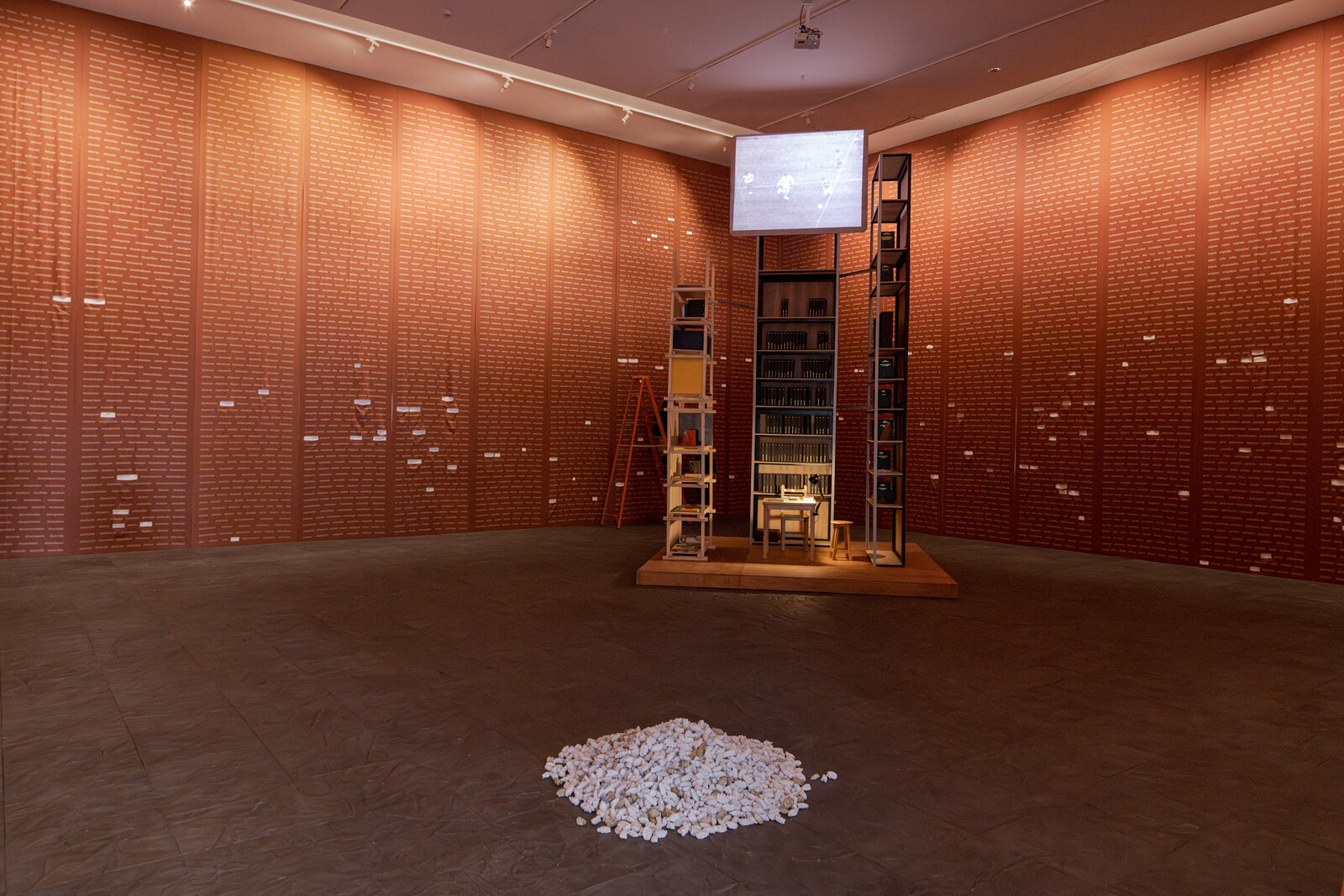

The main gallery groups three pieces, Palabras, palabras, palabras (2024) by María Isabel Arango, Todo Nombre es mi nombre (Gramática Nacional) (2024) by David Medina, and Mater/Madre (2024) by Mónica Restrepo. Mater/Madre is a small pile of papier-mâché forms of the hollow space inside a fist, made by the artist shredding and sculpting pulp from official but unidentified documents from the Ministry of Culture with her hands. Beyond the small heap stands Medina’s installation of a desk surrounded by high shelves displaying collections of books he has adapted using AI. One remixes the first and last names of the national registry of victims to produce a false but plausible compendium of names totaling the number of victims of the war. Another swaps words in a collection of books that President Samper decreed in 1996 every Colombian family should have in their home library, in an effort to unify the nation through state-imposed literary references.

A floor-to-ceiling installation by María Isabel Arango takes the influential history of Colombia by Marco Palacios and Frank Safford, Historia de Colombia: Pais Dividida, Sociedad Fragmentada (2002). Arango presents the whole tome with the words rearranged in alphabetical order, printed onto a terracotta-colored textile that wraps the entirety of the gallery. Visitors are invited to select a word that the museum docents cut to remove, and then gift to them. Over time, the accumulating holes in the fabric suggest censored documents.

The show’s criticism of the peace process is that the bureaucratic systems have primarily succeeded in reducing personal tragedies to self-referential nonsense through the transformative abstraction of language and curlicues of paperwork. At least two of the artists in this show are listed in the government’s victims registry. So their view is no empty accusation: that rather than address the violence that displaced nearly 10 percent of the country’s citizens, government agencies, multilaterals, NGOs, and academics working on the peace process have largely converted murder, rape, property seizure, and forced child conscriptions to empty statistics filling official documents endlessly produced and pushed around. Calling to mind political scientist James C. Scott’s criticisms of “legibility” in state administration as anything but, these artists identify and denounce empowered yet feckless authoritative agencies as their own front of violent erasure. The implicit question is: which is the real forced disappearance?

Sadly, given the show’s laudable aims, its criticisms land a bit soft. More exploration of the material conditions of the peace process might have helped Cerón be more specific about its failings. For example, it’s never mentioned that all the empty bureaucracy is a major economic motor supported by significant international development investment—Colombia was the top recipient of USAID funds in the Americas, and the recent loss of these funds is having a significant impact on the country, as programs which supported the peace process are closed,1 further endangering the fragile peace, including agreements with the FARC and the ELN. These funding streams supported a range of programs, from public health initiatives to poverty alleviation in rural areas. Their cuts will put the exhibition’s criticisms of the international development apparatus and its bureaucracy to the test.

Fragmentos has also been criticized as advancing the government’s narrative of peace, which papers over the fact that the violence hasn’t stopped. President Petro, himself an ex-M19 guerilla, was elected on promises of “total peace.” But with just over a year left in his turbulent term, he has yet to sign any agreements with militias who insist that the government has not made good on their promises, calling into question the government’s commitment to the peace process. Worse, the monument has been used to art-wash state violence: in 2021, the Ministry of Culture facilitated president Duque using Fragmentos to hold public meetings, without Salcedo’s or the board’s permission, in the wake of violent state crackdowns on civilian protestors that left more than sixty dead, thousands jailed, and hundreds disappeared. Salcedo’s monument, likewise, has been controversial: some have argued that it is exploitative of the victims who collaborated on its production and who appear in a film about the making of the work on permanent display. It seems, therefore, like a missed opportunity that Cerón did not frame the works in tension with Fragmentos as an institution, another imperfect product of the same problematic processes the artists here are critiquing.

Who knows if that would even be possible. As Restrepo says in her artist statement, paperwork is its own power. “The paper wins over the land. Paper accumulates, expropriates, and evicts.” But if we don’t precisely interrogate how that power is constructed or where it comes from, we remain stuck in the same circular conversations forever.

See “USAID Map Shows Countries Where It Spends Most Money,” Newsweek, February 3, 2025, https://www.newsweek.com/usaid-map-counties-most-money-2025073.