The experimental documentary Il Principe di Ostia Bronx (2017) tells the story of Dario Galetti Magnani and his life partner and collaborator Maury Fonte, better known on the beaches of Ostia as “Il Principe” and “La Contessa.” Directed by Raffaele Passerini, the film shows the duo in a variety of costumes performing improvised protests and scraps of scripts to sunbathing day-trippers from nearby Rome, all the while blasting music on a stereo. 1 Rejected by academia and mainstream theater in their twenties, the pair have spent decades recording each other delivering melodramatic and comic dialogues on the beach. As a temporary third member of the creative-unit-cum-chosen-family, Passerini turns our attention to queer ways of living, worldmaking, tender bickering, homemade films, and homemade pizza: which is to say, to art and to love.

Eight years after the film introduced the artists to an international audience—and confirmed them as icons to a younger queer community in Italy—their lives continue as before. Their celebrity and acknowledged cultural significance has not been translated into exhibitions or documentation of their performances and artworks in any tangible way beyond Passerini’s film. Like many artists who do not fit neatly within the taxonomies of commodifiable art, professional social networks, or brandable trends, their work has not been supported by grants, institutional acquisition, or commercial representation. This is what it means to make art from a marginalized position. As the state interferes in, and manipulates, cultural institutions in Italy and elsewhere, there is an increasing value in attending to cultural production, critical discourse and ways of living that fall outside of those networks.2

Ostia is at once Rome’s summertime seaside resort, a working-class neighborhood, a mafia stronghold,3 the location of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s notorious murder in 1975, and home to a world-famous archaeological site. To travel the 20 miles from central Rome, I took the train from the station named for the neighboring Pyramid of Cestius, built just a few years before the birth of Christ to memorialize—and entomb—the politician Gaius Cestius Epulone. On arriving in Ostia, I went to meet Galleti Magnani in order to see a second monumental artwork and archive, holding and memorializing an alternative history of Roman life: The Pyramid of Ostia Bronx.

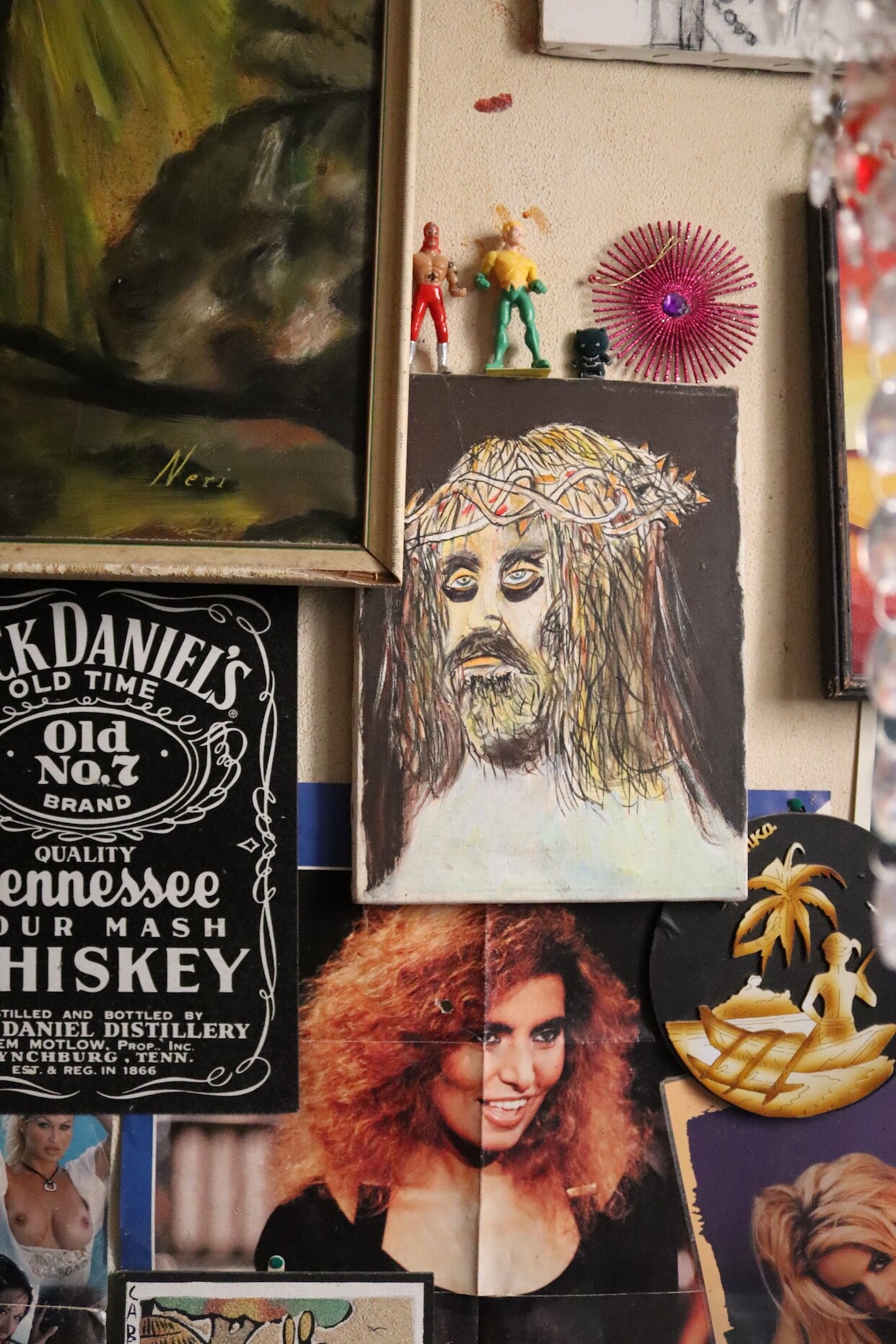

Dario Galetti Magnani, The Pyramid of Ostia Bronx (detail), 2010–ongoing. Photo by Eloise Fornieles. Image courtesy of the artist.

This second, metaphorical pyramid is housed in the artist’s apartment, a site-specific installation built over fifteen years of dedicated work. Galetti Magnani refers to it as a pyramid in part because the rooms become increasingly tight as you move deeper into the installation, as if moving up through tapering chambers; but the name also alludes to the fact that generations of his family lived in Egypt. And so he has weaved an inheritance of objects, images, and myths into the fabric of the artwork, an expression of the diverse cultural soils and migratory roots from which his family tree grows.

Following Galetti Magnani into his pyramid is like following a wild rabbit into a warren of kaleidoscopic materials. I caught glimpses of him in mirrors placed throughout the installation, leading me from room to room via narrow corridors. Books and defunct DVD players are repurposed as makeshift stages on which toy dinosaurs, clowns, dolls, and action heroes act out scenes amongst film posters, Obama badges, hair clips, centerfolds, religious icons, candies, cassettes, chocolate spread packaging, and clusters of glittering ornaments. The walls, floor and ceilings are adorned with tessellations of these found objects, punctuated by Il Principe’s post-punk paintings of pale-faced Victorian families, reminiscent of the B-movies he watched avidly as a child in the seventies and eighties. There are also paintings by his late mother, whose Chagall-like figures bring a gentle presence of maternal guardianship. Galetti Magnani started working on the installation the day after his mother passed away and her influence and care are evident. The old photographs, family heirlooms, and Halloween decorations create a recurring reference to death that defy the eternal youth of plastic toys and point instead to the pyramid as tomb.

In the western imagination, pyramids evoke horror films, colonial ransacking, museum exhibits, corrupt financial schemes, and alien conspiracies; the architecture is a portal to the afterlife and a space for shadowy imaginings. Paul Thek’s The Tomb (1967) played with this legacy by placing a wax self-portrait of the artist as a dead hippy inside a pyramid, as if to embalm and entomb the death of an era, killed by the Vietnam war, and succeeded by the finance-capitalism of the 1980s and the AIDS pandemic that would claim Thek’s life in 1988. The sculpture notoriously disappeared after the artist failed to pay for shipping fees, and the monument slipped from the material realm, preserved only in a small selection of photographs and the ghosts of our collective imagination.

Dario Galetti Magnani, The Pyramid of Ostia Bronx (detail), 2010–ongoing. Photo by Eloise Fornieles. Image courtesy of the artist.

The Pyramid of Ostia Bronx often points to the darkness of similarly labyrinthine works by Thek, Mike Nelson, and Thomas Hirschhorn, but is distinguished, firstly, by its particular sense of humor. Galetti Magnani’s immersive installation turns fear into comic artifice, rather than employing artifice to stimulate fear. This form of comedy provides access to deeply felt tragedy, conjuring grief and childlike joy in equal measure. Secondly, and more crucially, the artist’s installation is his home. The artist is present within, and activates, an aesthetic and a history that is materialized through the process of selecting, arranging, and living with objects. This heightens the visitor’s awareness of their relationship to the work: one steps into another person’s private space either as a guest or a trespasser. Being guided by Galetti Magnani through the space shaped the experience of it: he highlighted artifacts, provided stories and opened unseen chambers, as we turned sideways to squeeze through a density of crisp white shirts into a cavity lined with colorful necklaces.

The quantity of objects verges on compromising the functioning of his home and comes close to what some would describe as hoarding. As Rebecca R. Falkoff describes in Possessed: A Cultural History of Hoarding (2021), “the hoarder resembles an artist or an artisan whose identity as such is a function of the (composite) artifact he produces—facit artem. Diagnosis is, in part, an aesthetic problem.”4 If diagnosis of a practice’s tendency towards the pathological is an aesthetic problem, then who gets to make that judgment, and to what end? Who gets to define the difference between resembling an artist and being an artist? Marginalized groups repeatedly fight the violence of pathologizing terminologies that serve to exclude individuals from society and compromise their civil rights in the process. What is an archive but an organized hoard of material, deemed aesthetically or otherwise valuable?

Dario Galetti Magnani, The Pyramid of Ostia Bronx (detail), 2010–ongoing. Photograph by Eloise Fornieles. Image courtesy of the artist.

Sections of The Pyramid of Ostia Bronx are clearly a functioning archive: hundreds of VHS tapes of commercial films, B-movies and the documentation of the pairs performances are carefully stacked and labeled with a system of correlating newspaper clips, arranged and numbered in folders. It is a recurring feature of queer cultural production that its archives are typically to be found not in the institutions of art or the libraries of academia but in the homes of community members. Galetti Magnani treads a fine line between maintaining a functional domestic space, and expressing artistic brilliance, knowingly prioritizing his integrity as a practicing artist. Working within the refuge of one’s home can afford a level of safety, but it means his practice exists in the shadows. “They don’t know what they missed,” says La Contessa in the film, “They have no love for truth.”

When I ask Galetti Magnani who he imagines his audience to be, he very simply replies that he is making the installation for himself. It offers him calm and enables him to create a space that refers back to a happier time in his early childhood, before the death of his father. Family is a key theme of the installation, which includes many images of La Contessa and Il Principe over the three decades they have been together. They describe their meeting in 1994 as a miracle and Fonte travels from Rome to Ostia every day, since the installation might fulfil Galetti Magnani’s claim that he is “impossible to live with,”.

Dario Galetti Magnani, The Pyramid of Ostia Bronx (detail), 2010–ongoing. Photograph by Eloise Fornieles. Image courtesy of the artist.

Italy’s historical exhibitionism, enduring Catholic morality, and state propaganda means that light is not often shone on its alternative, tender, and anarchic cultural production. But artist-run venues, community collectives, clubs, squats, and domestic spaces provide a cultural network that isn’t easily regulated by the state, church, social mores, or market. These physical spaces in which individuals can feel safe and part of a community have become only more important as the far right infringes on cultural platforms and our minds are colonized by commodified and politically instrumentalized algorithms and the daily horror of virtual spaces.

Galetti Magnani doesn’t own a smartphone or have Wi-Fi. Indeed, when I spoke with La Contessa, they described the installation as a “womb,” which Galetti Magnani builds to feel safe from the outside world. The analogy is striking and captures the power of a womb, which like a tomb, can provide a holding space before embarking on the next iteration of existence. Galetti Magnani collects objects and subjects that are then materialized as his home: the pyramid is a place in which he both escapes the world and engages with it on his own terms. Be it a womb, a tomb, or a home, or some combination of the three, The Pyramid of Ostia Bronx offers a model of safe space: not by denying the existence of horror, death, and prejudice, but materializing and organizing their manifestations so that one may come to terms with the fear and grief they evoke. In giving space and time to these complex feelings we may then step back out into the world anew. This transformative potential derives from the installation’s emotional investment in the process of making and living, an investment that outweighs the purely material value of its composite objects. Like many queer philosophies, the Pyramid of Ostia Bronx centers love as the most enduring value.

Il Principe di Ostia Bronx can be watched at: https://guidedoc.tv/documentary/principe-di-ostia-bronx-documentary-film/

The recent meddling of the Italian government in cultural affairs, notably through politically motivated appointments and direct intervention in the programming of national institutions, is well documented. See for example: Elisabetta Povoledo, “Critics Complain That Italy’s Government Is Interfering in the Arts,” New York Times (December 12, 2024), https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/13/world/europe/futurism-exhibition-rome.html. Readers in Germany, the United States, and elsewhere will be able to supply their own examples.

Lizzy Davies,“Italy arrests 51 in Ostia anti-mafia raids” Guardian (July 26, 2013), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jul/26/italy-ostia-mafia-raids

Rebecca R. Falkoff, Possessed: A Cultural History of Hoarding (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2021), 6.