Everyone I meet in Kyiv is tired. Physically tired. Emotionally tired. Tired from the shrill loud whirl of the air raid app forcing them from sleep to the bomb shelters. Tired of the hours spent underground. Tired of the fear. I spoke to a woman on my night train from Moldova who had spent a week in Chișinău catching up on sleep.

It is therefore understandable that much of the work in the biennial PinchukArtCentre Prize—a gathering of twenty artists from across the country, all under 35, some displaced from their home regions to the safer west, some abroad temporarily—is bathed in a melancholic desire for calm. White is the recurring shade. In Mud Hut (2025), Anton Saenko has covered the entire gallery wall with the whitewashed clay mix used to build the titular countryside dwellings. Hung to this feature is one of the artist’s monochromes, also white. It is meditative, full of pathos, inviting the view to disappear, escape perhaps, into its pale frame.

A snow-white landscape by Mykhailo Alekseenko, a painting reminiscent of the land I had seen stretching out over nineteen hours on that train into Ukraine, takes the feeling further. Peaceful Landscape in a Nonexistent Museum (2025) has been installed in a room from which the artist has removed sections of wooden parquet flooring, the kind often found in museums, as if to delineate demolished walls. A ghostly landscape left in the ghost of a gallery. An army of tiny white clay soldiers line up on foot-high white plinths in a new installation by Vasyl Dmytryk titled Patrix: identical figurines, this time alone, appear in videos shown on floor-based flatscreens, documenting an action in which Dmytryk placed them on pavements and filmed the public reaction. Some people notice the tiny soldiers, and venerate them as heroes. One woman genuflects in the fashion I’d seen people do to the sea of photographs of dead young men in Maidan Nezalezhnosti, the square in central Kyiv; others get kicked and smashed, a mirror perhaps of the veteran’s life on returning from the front.

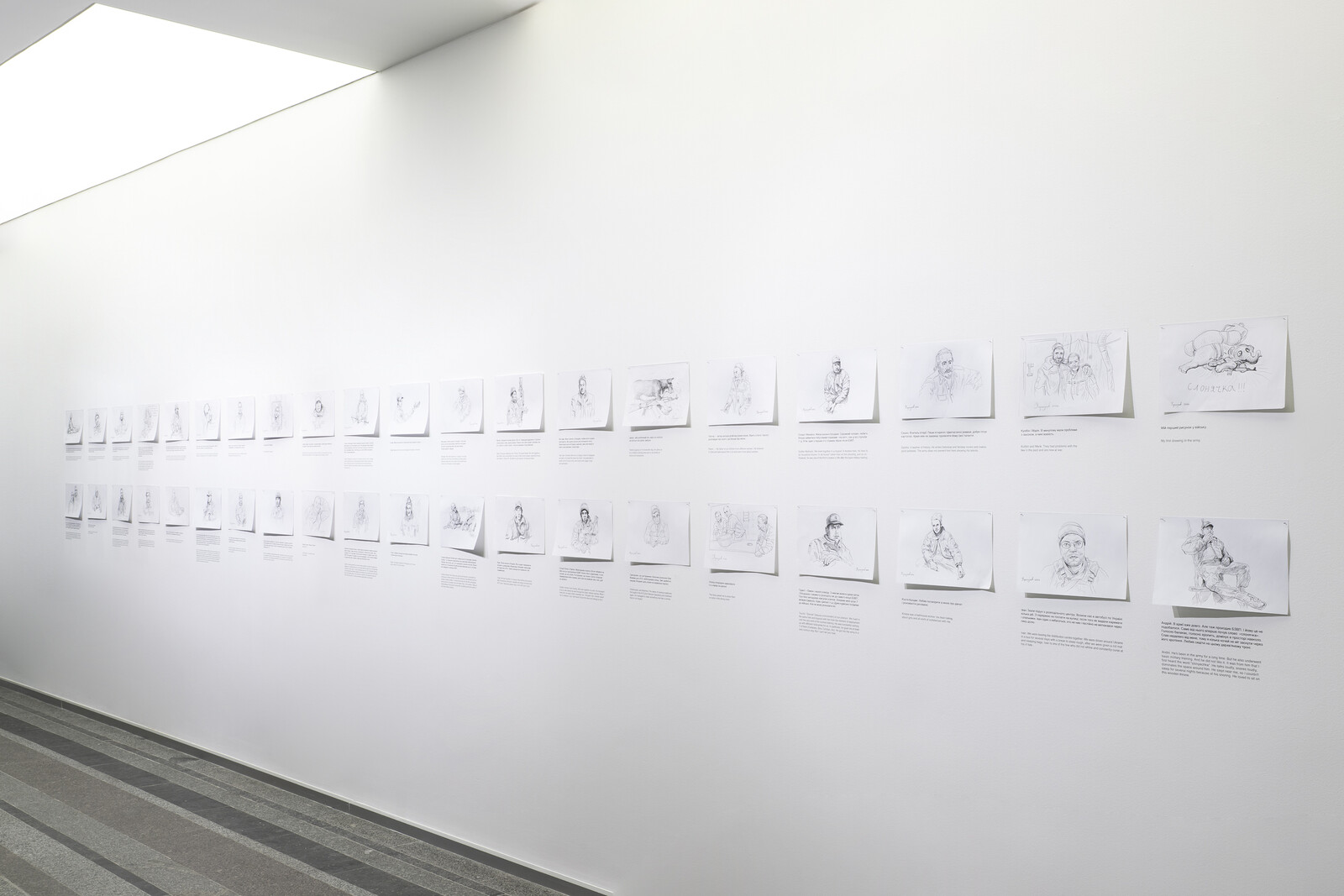

A large architectural black box—minimalist and slick—has been built to the specifications provided by Yevhen Korshunov in the room allocated to him. Korshunov didn’t make the installation himself: he can’t, he’s fighting on the frontline. Rather, he instructed the show’s curators to recreate the dugout shelter where he and his comrades grab what sleep they can, on cramped wooden bunks where they hope to be safe from enemy drones. Surrounding the structure are Korshunov’s annotated pencil sketches of the men he met during his basic training as a conscript, a hotchpotch of personalities far from the crowds he might typically have encountered on Kyiv’s art scene before the war: long-faced Yaryk (“his parents used to send parcels with homemade chebureki, belyashs, and wings”); burly, spread-legged Andrii (“he talks loudly, snores loudly, dominates the space around him”); Tsyhan, hugging a rifle as he dozes (“my favourite dog … not afraid of shots and explosions”).

An artist told me that, when the full-scale invasion occurred, in February 2022, the natural reaction was for him and his peers to make “posters,” by which he meant works of undisguised propaganda. Since then, however, as war has permeated the atmosphere (some of the youngest artists in the prize have only been exhibiting properly for three years, meaning they’ve never had a career in peacetime), an appetite has grown for more introspective stories.

A queue has formed outside the room screening the film What You Will Do When the War Continues? (2024–25), a forty-minute autobiographical tour-de-force by Vladislav Plisetskiy comprising TV clips, home video, and video phone footage. We see Plisetskiy as a toddler, born in the Russian town of Murmansk. We learn how he was sent to live with relatives in Ukraine after his father went to prison, how he gravitated to Kyiv’s anarchist queer scene. There follows an adrenaline-popping montage of goth-electro clubs and techno parties, chains, piercings, dildos, and fun-fun-fun sleepless nights. Then the tanks roll over the eastern border and choices have to be made. Most controversially, Plisetskiy includes vox-pop interviews with extremists from the Azov Unit, the far-right militia incorporated into the Ukrainian armed forces after the Maidan Revolution (the unit feeds Russian propaganda of Ukraine as a Nazi state). The artist dares to examine Ukraine’s ongoing problems in public. As Plisetskiy’s friend goes missing in action, these virulently homophobic men furiously deny the role of gay conscripts in the fight.

In the midst of this conflict, art has found its own front, channeling societal anxieties that might otherwise go unspoken; a place in which the contradictions and complexities of trauma can find an outlet beyond mainstream representation of strength and unity. One night in my hotel room, before the night curfew, I watched a magazine-format TV show in which a skit about a long-married couple’s sex life, performed in front of a live audience, incongruously gave way to a military band and images of the war dead. Murals of heroic soldiers decorate public walls and the Ukrainian blue-and-yellow is omnipresent. In the art on show in the prize, however, sadness, fear, and anger are allowed to coexist. Two works made this year make delineations between Ukrainians at home and abroad (Zhenia Stepanenko meditates of mediated horror in Scream from a Bubble Bath, her collection of horror film characters rendered as traditional porcelain figurines), and between men and women, the former expected to fight and banned from leaving the country (Krystyna Melnyk’s Impossibility of a Pure Gaze, a graphic Baconian painting of a flesh wound against youthful male skin, is a poignant vision of masculinity defined by physical fragility).

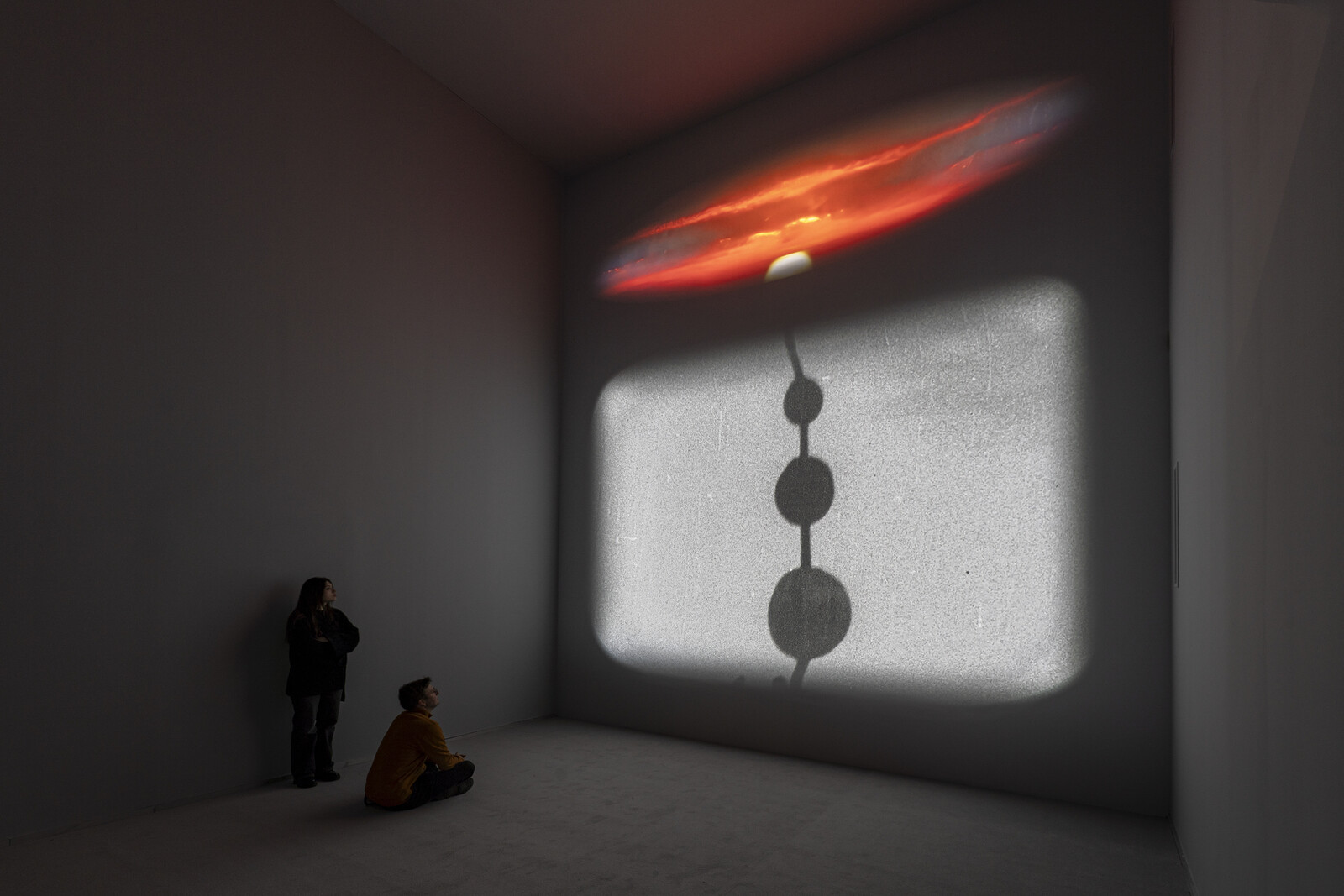

Stretching the full height of a vast gallery, viewable from the floor and an atrium, are two videos by Lesia Vasylchenko, Tachyoness (2022) projected above Night (2025). Having scoured over a century of material in the Ukrainian film archives, in the latter Vasylchenko compiles footage of the Ukrainian night sky from films and grainy news reels—the sky that now brings the ballistic missiles and anxiety after dark. Tachyoness is an AI-aided video of sunrises, a prayer that the new morning might come, and, as dawn light rises beyond the horizon, a note of optimism. Ukraine’s state museums are empty, their collections spirited to secret locations, and the public statues of its writers and composers are hidden behind protective boards and sandbags. However strange it sounds in the context, on the evidence here, it seems, nonetheless, art is undergoing a renaissance during the country’s darkest moment.