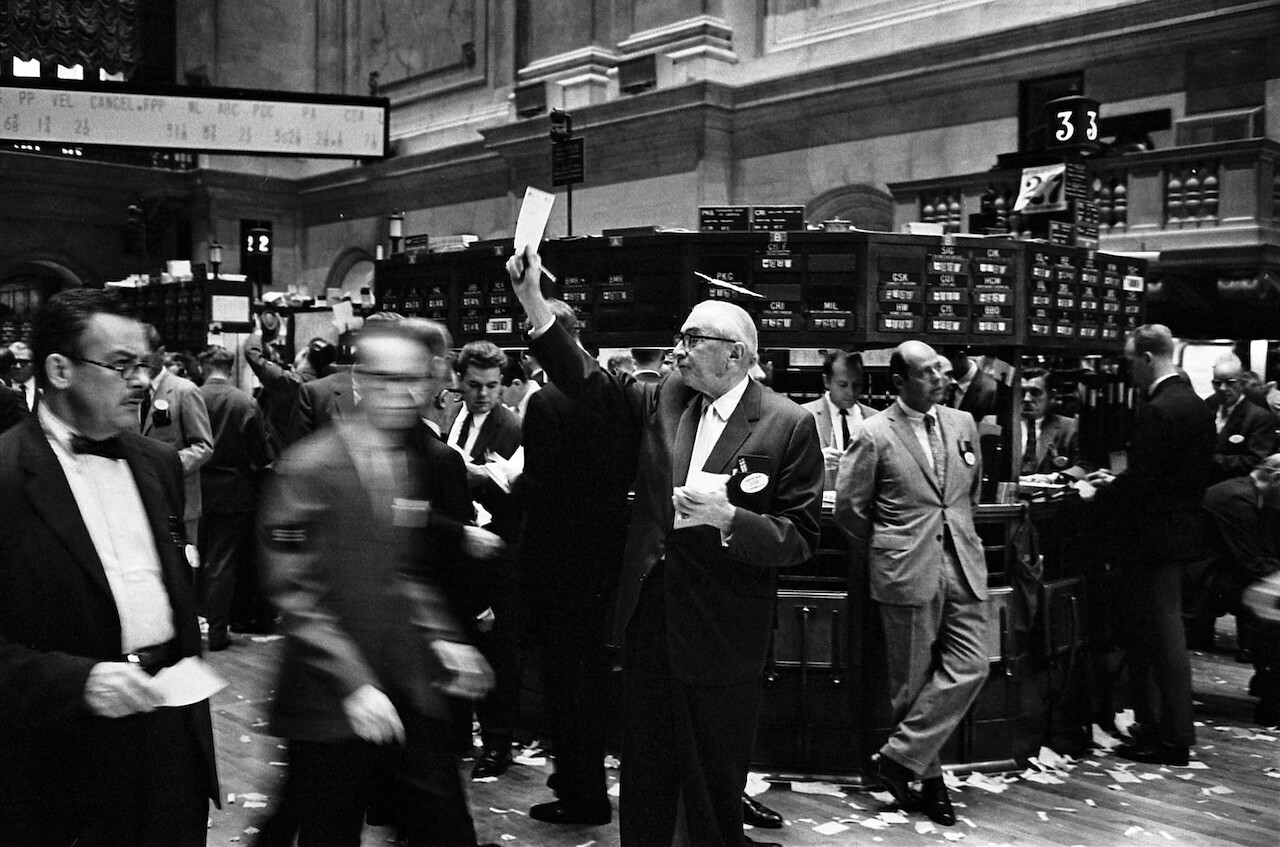

New York Stock Exchange, September 26, 1963.

Finance is everywhere in the cultural imaginary; it represents itself largely on its own terms, a set of appearances that do not correspond to its practice.

—John MacIntosh, entry on “Work” in Finance Aesthetics

There are numerous ways to categorize or periodize present crises. In no particular order: crack-up capitalism (Quinn Slobodian); organized abandonment (Ruth Wilson Gilmore); late fascism (Alberto Toscano, though the term does not name a period but rather sketches a framework of analysis);1 disaster nationalism (Richard Seymour); enshittification (Cory Doctorow); the financialization of daily life (Randy Martin); neoliberalism from below (Verónica Gago); and so on. It’s a maelstrom of modalities of domination that require more time and space than we have just to conceive it, let alone defeat it. The machinations behind how so much of the planet and its denizens have been rendered as financialized assets (or surplus to such assets) are hard to appraise with theoretical and statistical tools alone. We need to recognize how these transformations are sensed and lived. We feel the ravages of financialization every time our check bounces, or we receive yet another medical bill from a nefarious-sounding collections bot, or see our libraries close, replaced by a PO box for some untraceable housing management company named HOUSEZ4U <3. As the editors of the new Finance Aesthetics: A Critical Glossary put it, because “the finance economy constitutes both a performative power and a representational problem … the historical condition of global financialization obliges scrutiny from angles more unbounded and less ‘invested’ than those traditionally offered by the field and discipline of economics.”2

In her masterful Speculation as a Mode of Production, Marina Vishmidt (a contributor to Finance Aesthetics and dedicatee of the book) argues that the financialization of creative production and the aesthetics of financialization are at the core of the contemporary capitalist mode of production, offering a novel method of analysis that takes seriously both the claims and stakes of capital’s incorporation of the form of artistic labor—something that, in an orthodox Marxist perspective, would not be considered productive. “Creativity,” Vishmidt writes, “functions as capitalist populism, assuring every exploited worker and discontented artist that capital’s interests coincide with their own.” By “speculation as a mode of production,” she means to underline the creative, even artistic dimensions of capitalist valorization, expulsion, and of course speculation: the “conjunction of the characteristic valorization processes of art and financialized capital as two social forms that are related through the compatibility of their logics.”3

Many of the entries in Finance Aesthetics offer generative appreciations of terms, processes, and concepts that cut against the grain of more standard approaches. Thus the book explores not how animals are quantitatively valued and traded, but how they have historically served to give credence to the fictions of valorization and legal codes in the human kingdom (Leigh Clare LaBerge); not only how value continues to accumulate, but how value “names the movement of socialization” (Beverly Best and Richard Dienst); not only “extraction” as a modality of the Capitolocene but how capital masticates us through the money-form (Nicholas Alan Huber). Many of the entries have a poetic quality: “Money” by Phil Elvereum is a haiku; “Counterfeit” by Jonas Eika is a “spin-off” from his novel; “Gift” and “Invisible Hand” feature artworks by Hans Haacke; Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux’s “Gaming” offers a history of pinball’s criminalization. The most interesting editorial decision was adding “ghost” entries for each letter of the alphabet, marked in neon blue throughout the book, suggesting further pathways of inquiry. For “A,” for example, there are entries on “Amazon,” “Animals,” and “Arbitrage,” but “Abandonment,” “Algorithm,” “Art,” and “Assets” also appear as part of the matrix of references.

The problem of representing financialization, as Vishmidt notes, is that its technologies (credit instruments, debt, etc.) “are themselves terms of representation.”4 Gerald Nestler sums it up in his entry on HFT (high-frequency trading): “Technocapitalist resolution does not make us see and know; it makes us seen and known … We need to learn to sense anew, develop new senses, if we want to decipher the performative speech of technopower and nurture a new ecology of solidarity and care.”5 If finance capital is a fiction, or rather made up of fictional quantities and qualities, then we need literary and aesthetic tools to understand it. In his entry on “Fiction,” Jens Beckert writes, “What is the epistemological status of the expectations on which actors in financial markets base their decisions? They are fictional.” How to reckon with abstractions, real ones included, other than to recognize their role in building and destroying the world in which we live? Srinath Mogeri takes on this imperative as a fictional premise in his short story about a mass pandemic (the entry for “Death”). In this speculative scenario, people can pay three thousand dollars to continue living in the afterlife; under financialized capitalism, Mogeri suggests, cheating death is easier than cheating debt.6

How to describe the scenes of Musk and his young fascists openly transferring entire public-sector financial systems and technologies of governance onto their personal computers (probably covered in ketamine dust and Pepe stickers)? “Coup” is no doubt the most appropriate word. But the mechanics of this shocking takeover are not so foreign to the neoliberal playbook: casualizing, ripping apart, and then selling the leftover infrastructure for parts is now boomeranging—to borrow Aimé Césaire’s framing of fascism as a return of colonial expansion to European soil—from corporate raiders to the state. In this hellscape-in-the-making, it won’t be long until the US Postal Service is run by Amazon, air traffic by Starlink, and the Department of Education by some DEI-obsessed AI. Another word to describe it might be “disruption,” which Sarah Brouillette covers in her entry. Although the term is now more common as a masturbatory self-identifier for techno-capture and consolidation, Brouillette historizes its emergence in the realm of university austerity and privatization as “a desperate obfuscation of a brutality that is patently obvious, perhaps providing ameliorative balm to the brutalizers but not fooling many other people.”7 This ties in with Shannan Hayes’s entry on “The University,” which discusses its shift from a publicly subsidized good to a profoundly effective vehicle of speculation, fueled by the financialized system of student lending. Today this corruption of the university is eminently visible as a locus for the violent repression of popular movements that might disrupt expected returns on investment. The breadth of the glossary entries demonstrates that financialization is less an order of economic activity than a series of vast interconnected infrastructures, both ideological and material.

How then to “disrupt” the goals of techno-financialization? In their entry on “Organization,” Joshua Clover and Annie McClanahan point to other forms of disruption: riotous confrontations outside traditional sites of production, or what Clover elsewhere calls “circulation struggles.”8 Rebuking the orthodox separation between organization and spontaneity, they point to the Yellow Vests uprising, actions in 2019 by coal miners against their employer Blackjewel, San Francisco gig workers who blocked commuter buses and allied with sex workers to build mutual aid infrastructures during the pandemic, and the George Floyd rebellion. “Revolutionary movements spread neither by contamination nor resonance,” but rather “burst through the surface in a thousand places, akin because they share the same soil.”9 In entries like this, the glossary is most generative, offering interdisciplinary approaches that allow one to get a feel for contested terrains: sites and processes where extraction, casualization, absorption, policing, and surveillance can be actively negated.10

As Danny Hayward helpfully describes, Toscano’s “Late Fascism is not another entry in the now voluminous literature on the periodisation of fascism (post-fascism, crypto-fascism, parafascism), nor is it an attempt to decide whether current developments in US state politics can or cannot be classified as ‘fascist.’” Rather, the book is “an essay in how to analyse a political moving target (one that shoots back). It can also be thought of as a kind of performative method of description.” Danny Hayward, “Fascist Ships of Theseus,” Radical Philosophy 2, no. 17 (Winter 2024) →.

Torsten Andreasen, Emma Sofie Brogaard, Mikkel Krause Frantzen, Nicholas Alan Huber, and Frederik Tygstrup, introduction to Finance Aesthetics: A Critical Glossary (Goldsmiths Press, 2024), 2–3.

Marina Vishmidt, Speculation as a Mode of Production: Forms of Value Subjectivity in Art and Capital (Brill, 2019), 3.

Vishmidt, Speculation as a Mode of Production, 124.

Finance Aesthetics, 176.

See Julie Livingston and Andrew Ross, Cars and Jails: Freedom Dreams, Debt and Carcerality (OR Books, 2022) for an examination of how debtors’ prisons persist de facto in the US through the enforcement of auto debt via traffic policing.

Finance Aesthetics, 126.

Joshua Clover, Riot. Strike. Riot: The New Era of Uprisings (Verso, 2019).

Finance Aesthetics, 281.

Marina Vishmidt, “Activated Negativity: An Interview with Marina Vishmidt,” Makhzin, no. 2 (April 2016).