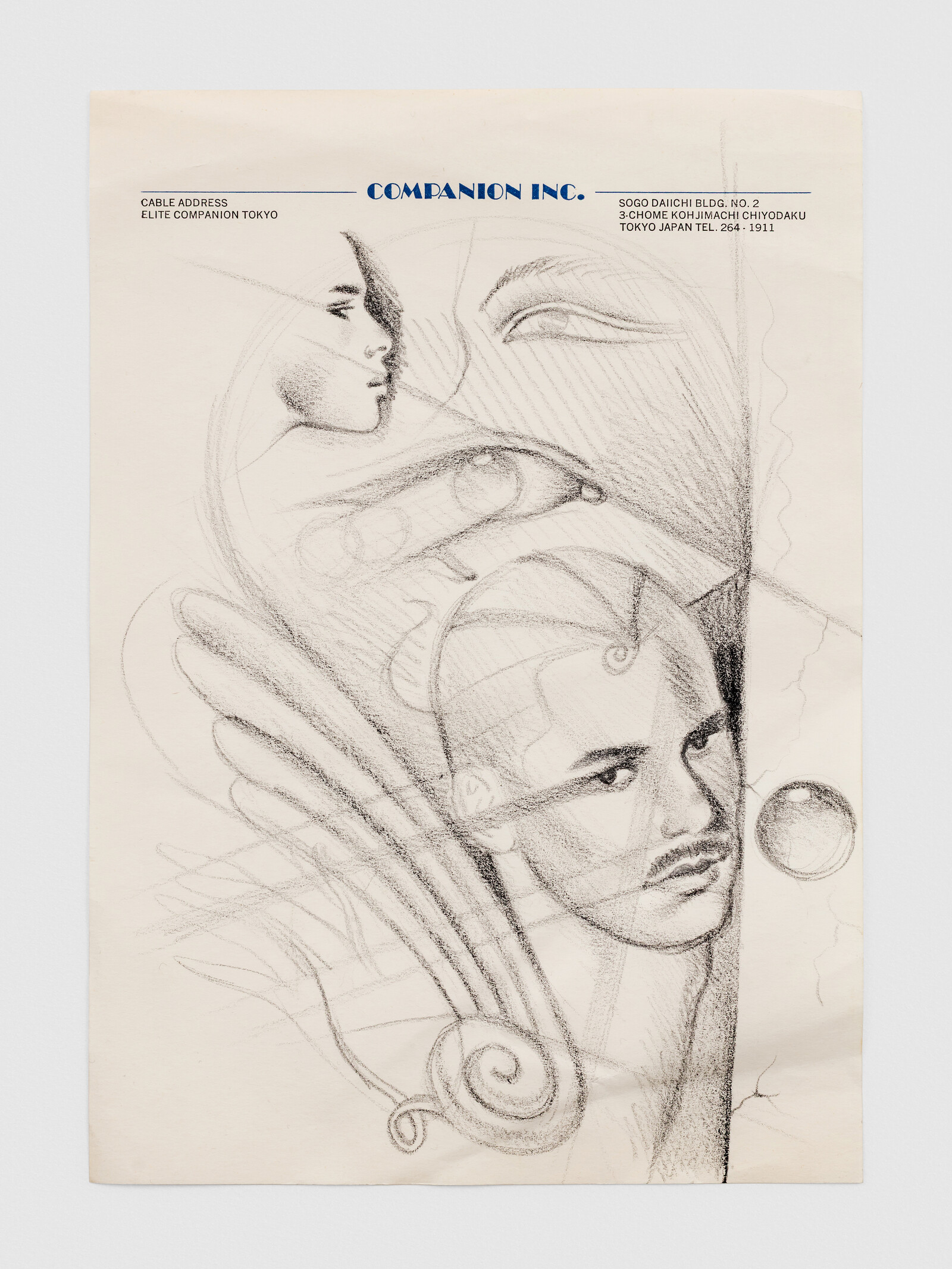

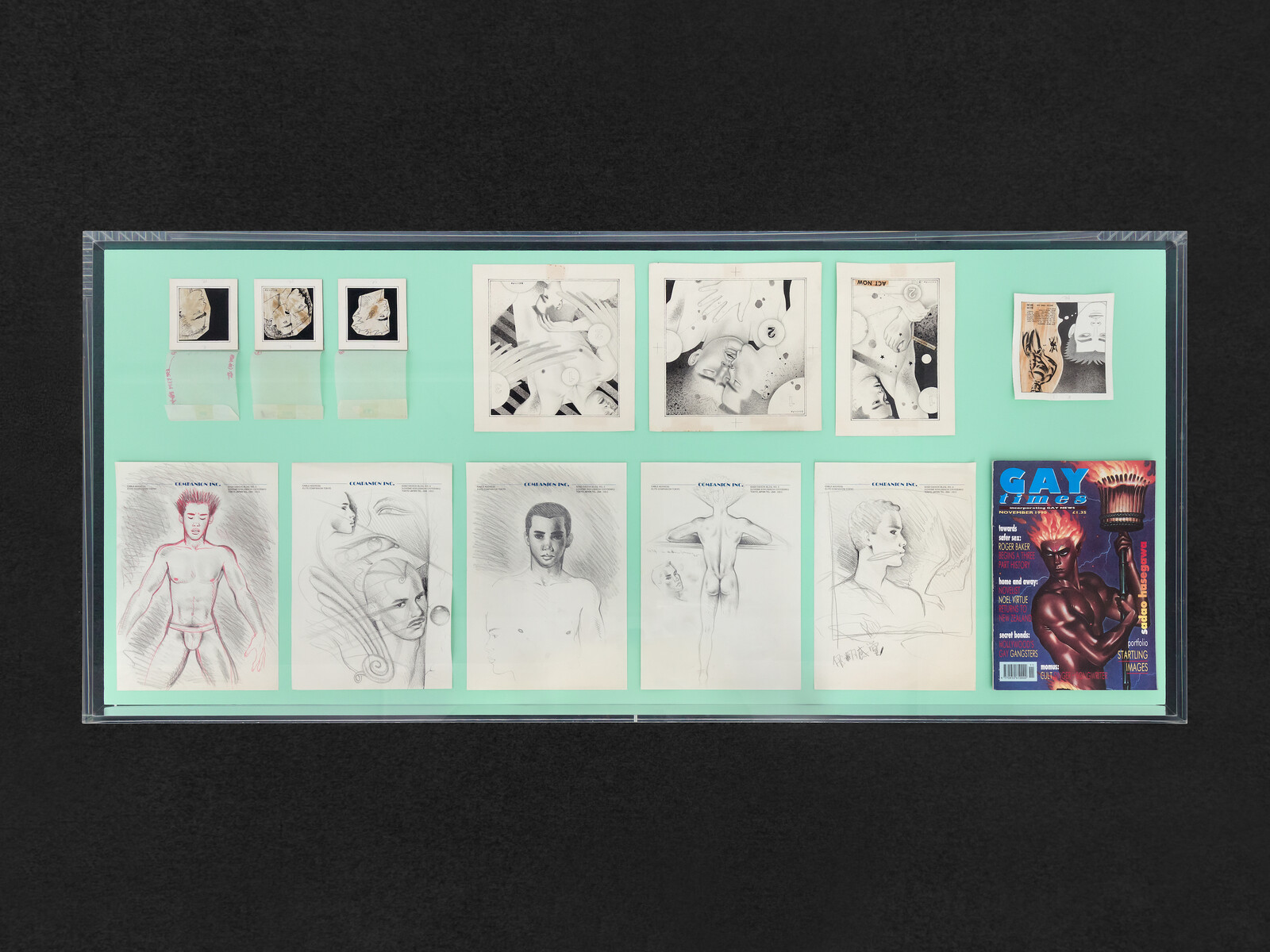

From the late 1970s until his death in 1999, Sadao Hasegawa was one of postwar Japan’s most prominent illustrators, and a major figure in the country’s burgeoning industry of gay magazines.1 This collaboration with Tokyo’s Gallery Naruyama—which has handled his estate since his suicide—is Hasegawa’s first solo show outside Japan: although his paintings and drawings were reproduced in magazines in the US, UK, and Australia, his concern that their erotic content would land him in trouble with Japanese customs prevented him from shipping them to arts institutions overseas. Suggestively titled after the corporate letterhead of paper on which he sketched, it presents a focused selection of works in a vitrine and on the walls of one small room, consisting mainly of designs for magazine prints—some of which still have their marked-up overlays.

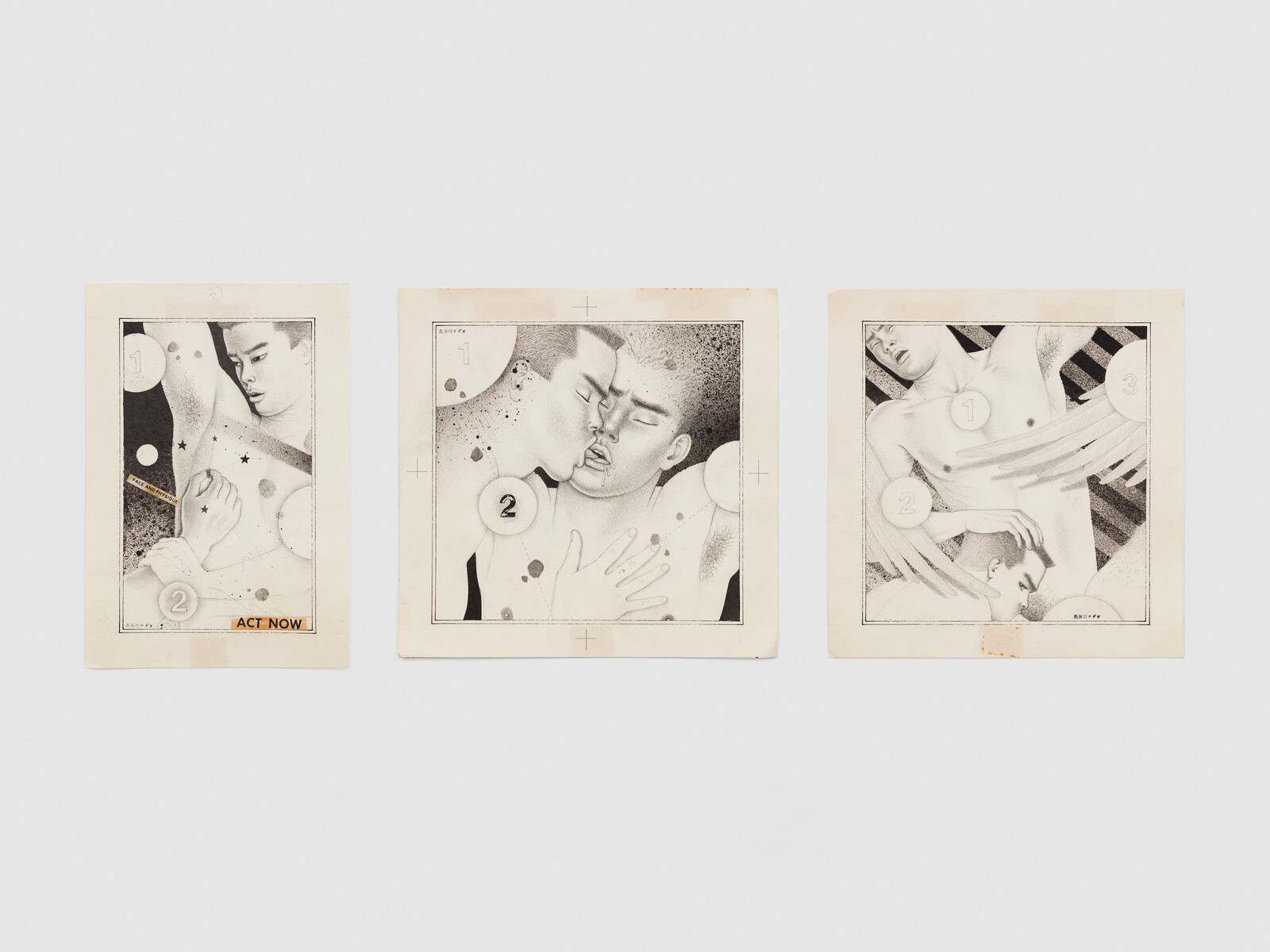

In a 1995 letter from Hasegawa to Durk Dehner, founder of the Tom of Finland Foundation, he articulated, in English, an intention of using mainly Asian “motifs” to create a “universe of beauty” that “differs from [the] Western point of view.”2 This utopian project sums up the show’s focus, part of which involves Hasegawa assaying the politics of queer miscegenation between East and West. A preparatory drawing for Barazoku—one of the most popular gay magazines in Japan—from the 1980s presents two overlapping heads in profile, one mustached like a Tom of Finland beefcake, the other beside him in a futuristic style, an Asian eye extending out and up, winglike. In another, an Asian man licks his lips at a tipped-in advertisement for sexy briefs, the copy in English, the model Western, the price in dollars—the suggestion, perhaps, that you can desire a hegemonic body type without aspiring to be it, teasingly subverting the postwar narrative of Western men preying on “effeminate” Asians.3

The self-taught Hasegawa reportedly named as key influences Tom of Finland and Go Mishima, the latter renowned for his illustrations of yakuza-tattooed men.4 But what distinguishes Hasegawa is the limitlessness of his world—where men can fuck each other as much as they want, without societal, national, or even species constraints. While he often explored Japanese tropes—kabuki, shunga—this exhibition emphasizes the perviousness of his view of culture and ethnicity, which he abstracted and amalgamated through a futuristic-mythological lens. The letterheaded drawings (ca.1979) show him layering and merging facial features, at times introducing non-human appendages such as wings or leaves—searching for a pan-Asian, mythological male beauty to be his utopian body politic. The artifice of his endeavor is referenced in a 1983 design for the cover of Samson magazine, with dotted lines marking out the symmetries of two godlike heads.

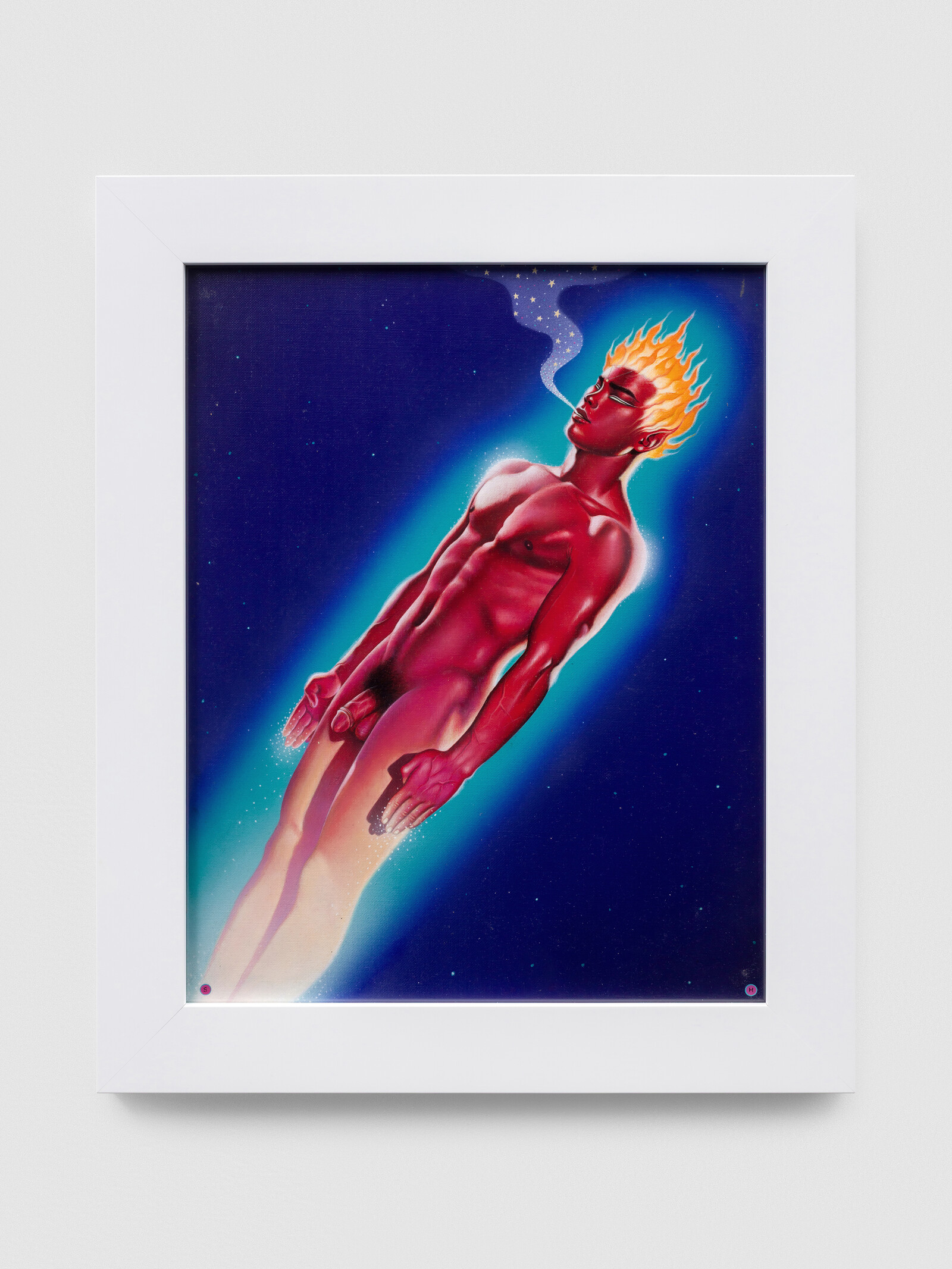

There is no place more limitless than outer space, a backdrop to which Hasegawa frequently returned. In the show’s only painting, That Floating Feeling (1980), a naked man sleeps or meditates in a celestial haze, a jewel between his eyebrows resembling a Buddhist urna, while his crimson skin and flaming hair liken him to Agni, the Hindu god of fire. A similar deity reappears brandishing a torch on the cover of the November 1990 issue of Gay Times, displayed in the exhibition’s vitrine. It feels pertinent that Hasegawa’s invocation of ancient spirituality allows for magic independent of technology—no spaceships, no “goggles”—in the era of Blade Runner (1982), when Japan was being increasingly orientalized (pronouncedly in this popular film’s exoticizing representation of the Japanese) on account of its hi-tech industry, as a place that existed only in the future.5

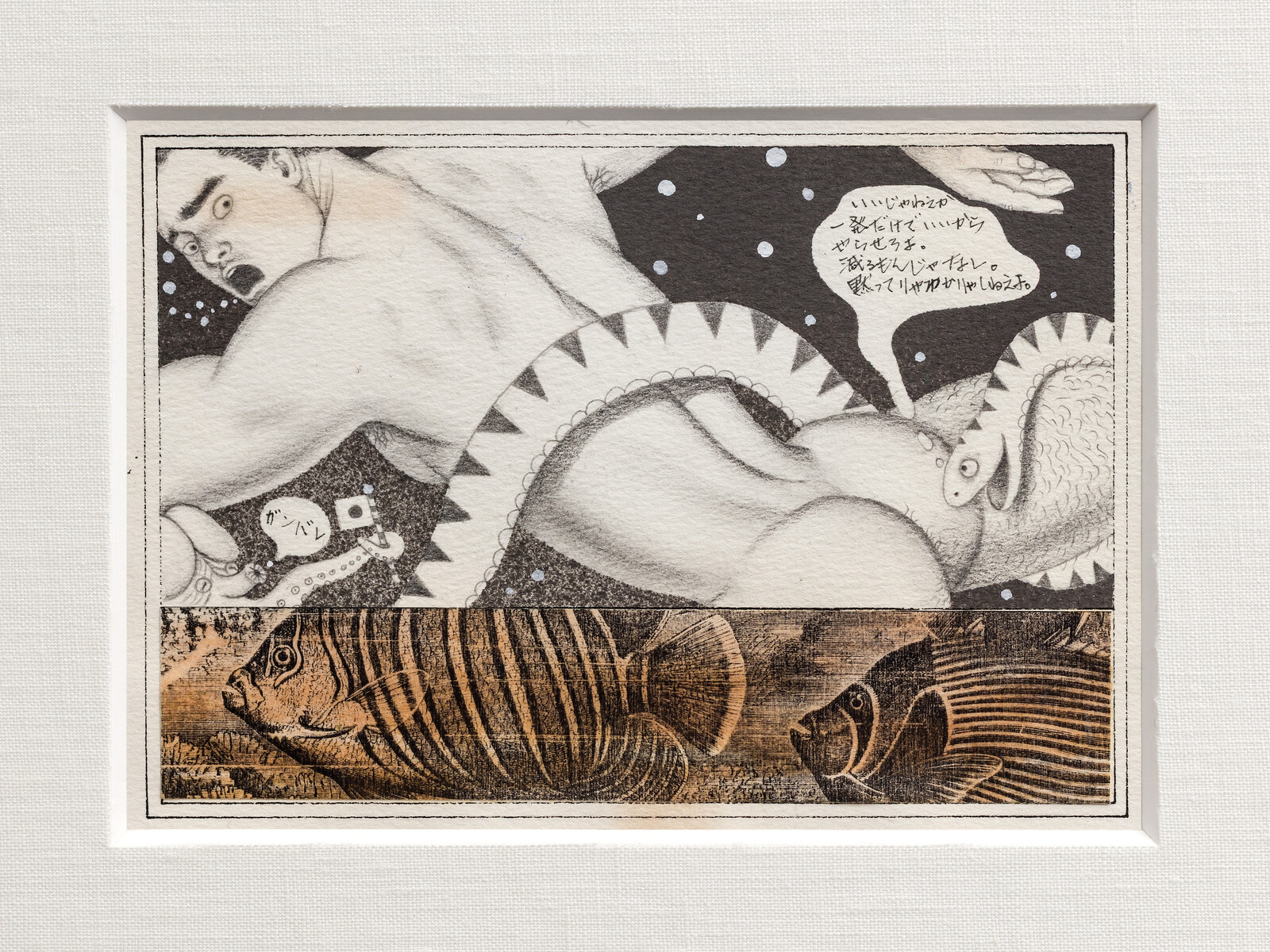

Along one wall, an exquisite suite of drawings (1980s) depicts the deep-sea sexual misadventures of a one-eyed giant (the phallic suggestion was unlikely lost on Hasegawa), his crewcut hunk, and their pet octopus with a bellend for a head. This mollusk is often seen waving a poxy Japanese flag—queering both “tentacle erotica” and nationhood, with the trio inhabiting an indeterminate “Japan” unto their own. Collaged at the base of each drawing is a print depicting a marine animal cut from a book of illustrations originally drawn by the nineteenth-century English naturalist Richard Lydekker, Hasegawa undermining their heteronormative authority with humorous juxtapositions; a spouting whale, for instance, reads as ejaculatory beneath the wildly copulating men. Thus Hasegawa used the gay magazine as a site of erotic fantasy that—by being counterfactual—was also backhanded critique, creating a queer-ecological utopia in which nation and nature are boundless.

The Japanese gay magazines that flourished from the early 1970s featured essays, fiction, letters, personal ads, photography, and art, almost always of a sexual or pornographic nature; Jonathan D. Mackintosh, Homosexuality and Manliness in Postwar Japan (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2009), 3–7.

Letter from Sadao Hasegawa to Durk Dehner, February 13, 1995, reprinted in the press release for “English Companion Inc.”

On this complex narrative, shaped by the American Occupation of Japan and its legacy, and manifested as both a reality and a submissive fantasy in magazines such as Barazoku, see Mackintosh, Homosexuality and Manliness, 111–17.

see Thomas Baudinette, “Sadao Hasegawa: A radical cosmopolitan voice in Japanese gay erotic art,” in Sadao Hasegawa (London: Baron Books, 2022).

Dawn Chan, “Asia-Futurism,” Artforum (Summer 2016), https://www.artforum.com/columns/asia-futurism-229189/; in some respects, Hasegawa answers Chan’s question: “If Afrofuturist thinkers have created speculative realms of their own accord, carving out counterfactual worlds that might cast the shortcomings of our current one in high relief, might there be analogous ways for Asian artists to recast techno-clichéd trappings toward more generative ends?”