The Lebanese artist Abdel Hamid Baalbaki painted four major murals in his lifetime. Baalbaki called them murals, but in reality they were large-scale oil or acrylic paintings on canvas that strived for monumentality. They combine references to historical events, religious rituals, and performative reenactments. Though aware of the Mexican muralists David Alfaro Siqueiros and Diego Rivera when he painted these works in the 1970s, Baalbaki was inspired by the Iraqi modernists Jewad Selim and Kadhim Hayder, who had turned to archeology and mythology, a decade earlier, to form the elements of a new national culture.

For all their size, however, Baalbaki’s murals proved vulnerable. One of them, titled Ashura (1971), was either stolen or destroyed when the Institute of Fine Arts at Lebanon’s public university was ransacked during the country’s fifteen-year civil war. Another, titled The Fall of Al-Nassar (ca. 1972–74), was cut into pieces and likely discarded in Paris. The remaining two are now facing each other, like old friends, on either side of a small gallery, in a modest but revelatory tribute at Beirut’s Sursock Museum.

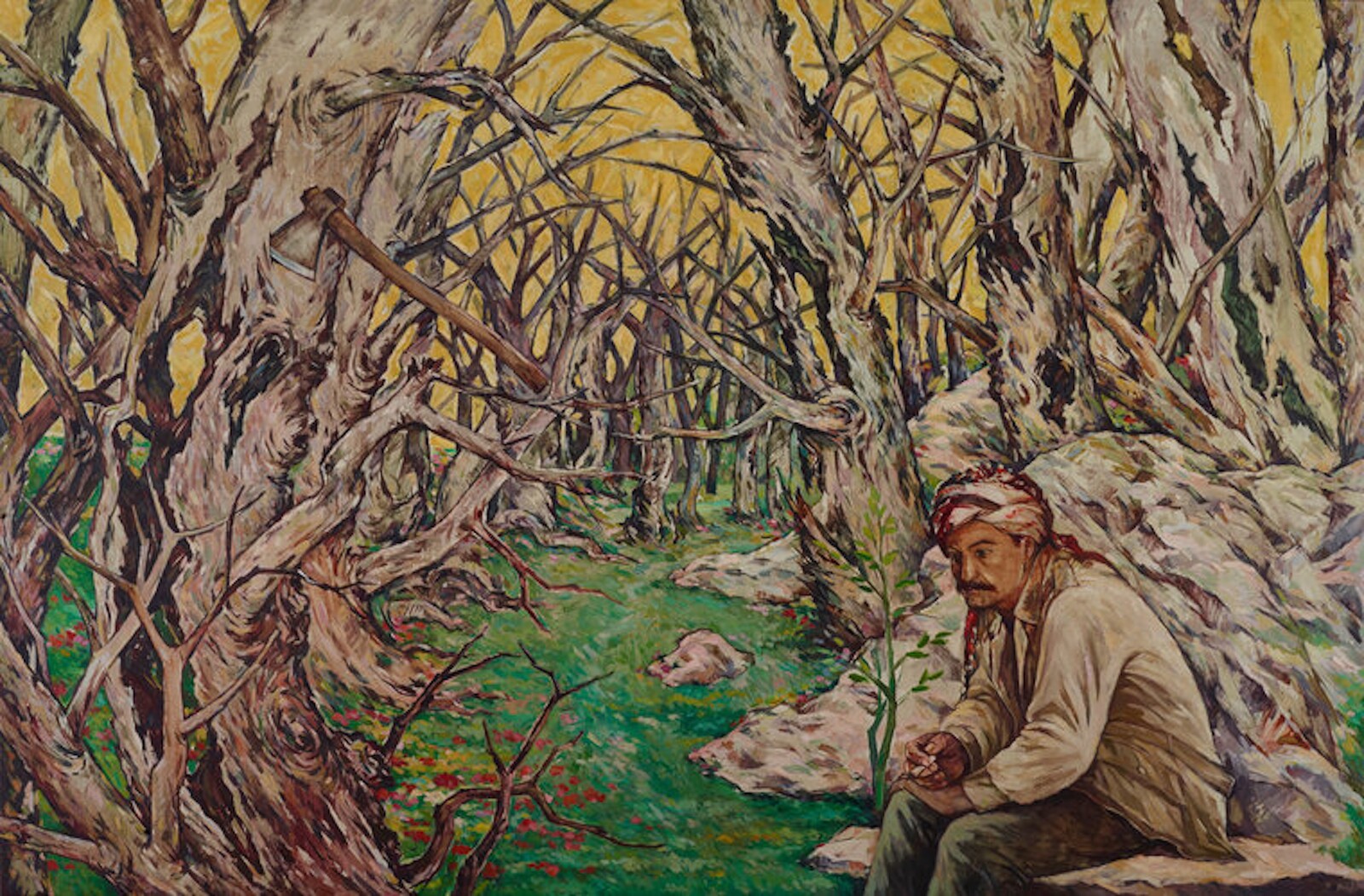

“Tribute to Abdel Hamid Baalbaki: Ode to the South” includes some forty paintings and red-chalk drawings. The first of its two rooms delves into Baalbaki’s work as a painter of social life, with intimate sketches of his children alongside group portraits of religious pilgrims, outrageous chronicles of local gangsters, or qabadayat, and a judicious display of archival effects. The second room shifts to political traumas and environmental disasters. Here, Baalbaki’s murals frame a bench for contemplation, with another large painting, titled Al-Hattab [The Woodsman] (1990), of a man seated at the edge of a ruined forest, hanging on the adjacent wall.

Set in relation to one another, the murals echo the weeping women of Youssef Howayek’s Les pleureuses (1930), a limestone sculpture that previously anchored Beirut’s Martyrs’ Square and currently stands on the museum’s esplanade. Brought together on the grounds of the same institution, Howayek’s women and Baalbaki’s murals partake of an ongoing conversation about how artists confront nationalist symbols while approaching more tenderly the delicate, diverse social fabric tattered by endless wars and the exploitation of difference.

Baalbaki’s extant murals are themselves of two minds. Deir Yassin Massacre (1973) recalls the Israeli killing of Palestinians in one small town in 1948 through an otherworldly language of white doves, hooded figures, and liberated souls. The compositional space is flat, the figures folkloric. A scene alluding to death and destruction is everywhere festooned with flowers.

The War Mural (1977), by contrast, was painted as an immediate response to a 1976 massacre in the coastal town of Damour, emblematic of the cyclical violence marking the early stages of Lebanon’s civil war. Compared to the ethereal melancholy of Deir Yassin, The War Mural shows palpable disgust for the grinding futility of armed conflict. With an allover palette of raging reds and oranges, it crams smoke, fire, and piles of rubble together with anguished bodies and a terrifyingly oversized owl, who appears to have incubated a rabid rooster. In ways that foreclose rather than encourage interpretation, the painting has often been called Lebanon’s Guernica.

But Baalbaki was never Lebanon’s Picasso, not because he wasn’t prominent or canonical but because such analogies are meaningless. They obscure the thing they try to explain. The archival displays at Sursock avoid comparison to a western standard and instead tell a brief, cogent story of who Baalbaki was—a poet and critic as well as a painter—and where he came from.

Born and raised in the village of Odeisseh, Baalbaki immersed himself in the history of Jabal Amil, another name for South Lebanon, which was a major center of Shiite learning in the sixteenth century and enjoyed relative autonomy in the late Ottoman Empire under the leadership of Nassif al-Nassar (the subject of Baalbaki’s second mural, lost in Paris).1 In the late 1950s, he moved to Beirut’s southern suburbs. He worked in the port, went to night school, did a stint at teacher’s college. In the late 1960s, Baalbaki attended the Institute of Fine Arts, where he won a scholarship (on the strengths of his first mural, lost in Beirut) to the École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

All of the work in this exhibition dates from the period after Paris. Baalbaki found the French capital lonely and cold. After three years, he returned to Lebanon, and then for three decades, he made the most compelling art of his career while railing against the “salon paintings” of his peers.2 And then he was largely forgotten. By the twenty-first century, the artist was best known as father and uncle to the contemporary artists Oussama, Ayman, and Mohamad-Saïd Baalbaki.

A reappraisal of the elder Baalbaki’s work began in 2009, when The War Mural served as the centerpiece of a group show called “The Road to Peace,” organized by the art dealer Saleh Barakat for the Beirut Art Center. Yet that shed no light on the rest of Baalbaki’s practice, which was principled, quixotic, and defiantly anti-bourgeois. What makes the current exhibition, curated by Sursock’s director Karina El Helou, so effective is that it shifts the grandiosity of Baalbaki’s murals onto the museological equivalent of a three-legged stool. Here, the murals are balanced out by Baalbaki’s landscapes of South Lebanon, and by his portraiture, which shows a remarkable sensitivity to class.

In that sense, the most arresting painting in the exhibition may be Baalbaki’s portrait of two Eritrean women promenading on Beirut’s seaside Corniche with a small child in a pushchair. The Little Gentleman (1982) follows an earlier painting and preparatory drawing (neither included here) of an Ethiopian woman reading a newspaper on a Beirut balcony. Artists in the Middle East rarely acknowledge much less center the foreign domestic workers ubiquitous in the region since the late 1970s, recruited under a kafala system (“sponsorship” in Arabic) shockingly conducive to abuse.3 Baalbaki not only made such workers his subject, he maintained their dignity.

Toward the end of his life, Baalbaki returned to South Lebanon. He built a house and made plans for it to become an art center and library for the region. Then, last fall, Odeisseh was razed to the ground by Israel’s latest war. Baalbaki’s house was destroyed. The writer and critic John Berger always insisted that hope had nothing to do with optimism for the future. It was the courage to claim joy in the present in the face of abjection.4 For Sursock to honor Baalbaki now, to share his legacy and vision, shows exactly that hope and courage.

Gregory Buchakjian, “Abdel-Hamid Baalbaki,” in Abdel-Hamid Baalbaki, 1940–2013 (Beirut: Saleh Barakat Gallery, 2018), 30–32.

Buchakjian, “Abdel-Hamid Baalbaki,” 45.

For an excellent account of the kafala system, see Sumayya Kassamali, “Kafala in the Time of the Flood,” Public Books (March 25, 2025), https://www.publicbooks.org/kafala-in-the-time-of-the-flood/.

“Aimé Césaire’s Return to My Native Land: John Berger in Conversation with David Constantine,” London Review Bookshop Podcast, May 27, 2014.