https://www.theblackwellschool.org/

Through the end of May, e-flux Education will focus its coverage on the United States, examining educational institutions in the American South and Southwest in particular. With attention paid to the specificities of each program and its pedagogies, the upcoming features will also consider the surrounding regions’ dense legacies of segregation, slavery, and frontierism alongside more contemporary reformations of schooling, museology, and justice.

Now it was time to close the casket and lower it into the grave. Everything had been perfect up to this moment until two pall bearers, who had not rehearsed, were to lower the casket with dignity. They started pulling against each other in disagreement, which was followed by anger, and then a volley of Spanish cuss words # % @ * $ * ? The solemnity turned into titters, then giggles followed by hilarious laughter as the bearers threw dirt at each other.

What a GREAT FIASCO!

—Blackwell School teacher Evelyn Davis, “The Last Rites of Spanish Speaking,” 1954

Well, we just decided to get a little box. We’ll put the dictionary in that little box and we’ll do a ceremony. Rafael Melendez dug him out. We had a beautiful ceremony. And it was nice, it turned out to be the best. Of that reunion, that was the best: the digging up of Mr. Spanish.

—Blackwell School alumna Maggie Nuñez Marquez

In 2007, a group of former Blackwell School students met in Marfa for an unofficial reunion. During the gathering, the alumni staged a ceremony that they called “Unburying Mr. Spanish,” with the intention of symbolically revoking another rite that had happened at the school fifty years prior. Attendees Sally and Richard Williams brought a Spanish dictionary, purchased on a recent trip to El Paso, and placed it in a small coffin. With the help of fellow alumni Maggie Nuñez Marquez and Rafael Melendez, they dug a hole in the soil and marked the spot with a wooden cross inscribed with the word “Spanish.” After placing the miniature coffin into the hole, the group promptly “unburied” it. Sally Williams then removed the dictionary from its casket and triumphantly raised it over her head.

In 1954, Evelyn Davis, a teacher at the Blackwell School, sought to prohibit students from speaking Spanish at the school. She established a ban on the language, marking its enactment with a mock burial she dubbed “Burying Mr. Spanish.” A segregated school for Marfa’s Hispanic children, the Blackwell School taught students whose first—and often, only—language was Spanish. For Davis’s ceremony, students were made to deliver speeches, wear pallbearer costumes, and officiate the rites of a Spanish dictionary, which was placed in a cardboard coffin and lowered into a grave on the school’s property. Students also wrote “I will not speak Spanish in school” on small pieces of paper, which were placed in a cigar box that was similarly interred. After the ceremony, speaking Spanish at the school was forbidden. Nuñez Marquez recalled that, on one occasion, she was spanked and sent home for three days for not complying.1

Davis believed the ban was a necessary measure to “perfect” the students’ English.2 A contentious mission, this endeavor was intended to aid their assimilation during an era when English had often been kept away from Hispanic students in order to justify their segregation on language-proficiency terms. The education scholar Victoria-María Macdonald has examined language’s role in maintaining segregated education in the US, stating that “Anglo school administrators utilized the justification that Mexican Americans needed to be segregated because their language skills were inadequate, [they] suffered from language deficiencies, and were dirty.”3

Davis’s ceremony was held near the school’s flagpole, from which the American flag billowed in the wind, presiding over the students’ forced submission to this Anglophone campaign. A former student lamented: “they buried the Spanish language. And the flag of the United States on one side. To me it was sad, for somebody to do that.”4 Other former students, in retrospect, acknowledged the potential benefits of assimilation. “The idea was great; the idea was to try to get all the Hispanic kids to speak English only,” alumni Joe Cabezuela stated.5 These contrasting perspectives indicate that the Blackwell students’ personal experiences at the school were nuanced, echoing the competing societal pressures that Hispanic communities faced in twentieth-century America.

Blackwell School alumni Sally and Richard Williams officiating the “Unburying Mr. Spanish” ceremony during a class reunion on the school’s grounds in Marfa, Texas, 2007. Courtesy of the Blackwell School Alliance.

As the sole public school for Hispanic students in Marfa for over six decades, the Blackwell School typified Texas’s custom of enacting de facto segregation, despite there being no state laws that required it. In 1889, the young town of Marfa, freshly established as a water stop and freight shipping station for the Southern Pacific railroad, converted a former Methodist Church into its first school. Initially, it welcomed all children, but three years later, the town then built a separate elementary school for white, English-speaking students. In 1909, Marfa’s school board authorized construction of a new schoolhouse for children of Mexican descent; it was named the Blackwell School, after a longtime principal named Jesse Blackwell, in 1940. Following the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, formal segregation in American schools became a thing of the past, and the Blackwell School shuttered the following year. After being briefly turned into a vocational school, the building subsequently remained empty and disused for decades.

Before the Blackwell School reunion in 2007, rumors had begun to circulate that the school’s still-empty building was under threat of demolition. Responding to these fears, the alumni formed an organizing body they called the Blackwell School Alliance, and, after appealing to Marfa’s school board, succeeded in securing a ninety-nine-year lease on the building. Following this victory, alumni began donating hundreds of photographs and objects, such as yearbooks, event programs, uniforms, trophies, and other memorabilia, to the Alliance. Now in official possession of the school’s last remaining adobe building and a significant collection of historical objects, the Alliance converted the site into a museum to commemorate the students’ experiences during their time at Blackwell against the backdrop of segregated education’s histories and legacies in the US.

At first glance, one might characterize the museum as solely representing the story of a historic and now-resolved American issue. If the school closed in 1965, then are the objects and the stories they tell simply buried in the past? What is the need for such a museum, beyond highlighting historic stories and demonstrating America’s shameful but now supposedly resolved former self? While the Blackwell School does indeed largely dedicate itself to chronicling its past, both the direct and indirect impacts of this story are tangibly felt today on multiple societal levels. In an interview, the museum’s former president, Gretel Enck, reflected on the paradox of celebrating the students and their time at the school while prejudice against Hispanic and Latino Americans remains rife: “I used to say I longed for the day when the Blackwell School isn’t relevant,” Enck said, “but we’re not there.”6

In 1896, the US Supreme Court used the “separate but equal” doctrine to rule that segregated education did not violate the Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment for equal protection under law for all people.7 As long as the same facilities and services were offered to all races, segregation could be enforced by local and state governments. Although this ended in the mid-twentieth century with landmark Supreme Court cases like Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional in 1954, scholars studying Hispanic, Latinx, and Chicano/a education in the US have observed that its negative effects persisted long after. Dennis J. Bixler-Marquez, a professor of Chicano Studies at the University of Texas El Paso, has noted that after the repeal of de jure segregation, “very few programs had been developed that successfully addressed the unique educational needs of Chicanos by the mid-1960s.”8

In a 2020 essay, Timothy Mattison, who previously served as the Director of Policy and Research for the Texas Public Charter Schools Association, examines the lingering effects of segregation in the state, arguing that “since the 1970s, desegregation efforts failed to keep the promise of equality in the 14th amendment.”9 He references Sean F. Reardon and Ann Owens’s study of Texas education, which reported that nearly half of the state’s students of color, in contrast to 8.3% of White students, attended high-poverty schools. Mattison also cites Julian Vasquez Heilig and Jennifer Jellison Holme’s 2013 research, showing that “Hispanic students in Texas [remain] highly segregated based on ethnicity, poverty, and language ability.”10 In light of these historic and contemporary inequalities, over the past two decades, the Blackwell School Alliance developed a self-run museum in extraordinarily innovative ways, continually pointing to the importance of its existence through its unique collection of donated objects and first-person accounts.

Earliest-known photograph of the Blackwell School in Marfa, Texas, built in 1909 for the town’s Spanish-speaking students. Courtesy of the Blackwell School Alliance.

(8) the original historic building and grounds on which the Blackwell School building stands provide an authentic setting to commemorate and interpret the history of the Blackwell School

—Public Law 117-206, 117th Congress, Blackwell School

National Historic Site Act, October 17, 2022

Remarkably, this small museum has been able to embed itself in one of the most well-known centers of American heritage. On October 17, 2022, former President Joe Biden signed a bill to establish the Blackwell School as a National Historic Site. Defined as officially recognized areas of national historic significance in the United States, only eighty-five sites in the country have been given this designation. The bill was ratified only after a long campaign by the Blackwell School Alliance—for which its members traveled to Washington, DC—to have the school, its building, and the site permanently protected and put into the care of the National Park Service. Due to its status as the “only extant property directly related with Hispanic education in Marfa,” as its Historic Site Act bill declares, the building and site of the former school are now permanently protected. The National Park Service is in the process of taking over maintenance of the museum and building, while the Blackwell School Alliance will maintain a high level of managerial control in perpetuity.

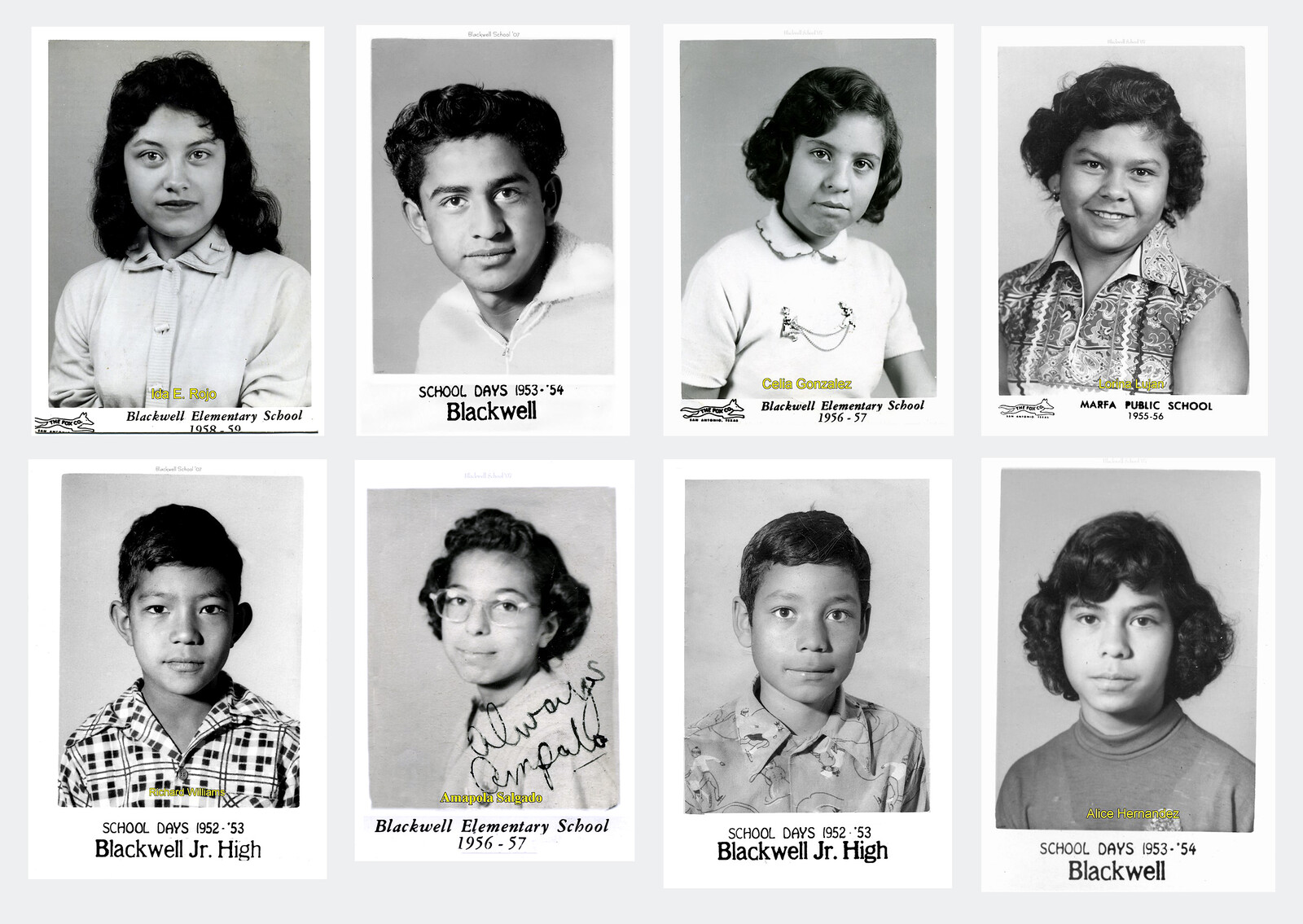

In the museum’s early years, Richard Williams volunteered as its archivist, digitizing every photograph that had been donated or loaned. As he worked through the collection, Enck noticed that most of the photographs were “fading away in the sunlight,”11 and expressed a deep sense of relief that they were being digitized. For the Blackwell School, the prospect of these images deteriorating was especially dire, considering the scarce archives of the history of Hispanic segregation in the United States. Over seven hundred school pictures—yearbook and class portraits, photographs of student athletes, graduation ceremonies, and proms, and other snapshots of student activities—have now been compiled and uploaded to an archive on the Blackwell Alliance’s website. The repository provides a crucial window into a history that had long been overlooked, marginalized, and at risk of being forgotten.

A number of scholars have studied the mishistoricizing of Mexican American history by white Americans. In her 2001 essay “Hispanic, Latino, Chicano, or ‘Other’?: Deconstructing the Relationship between Historians and Hispanic-American Educational History,” historian Victoria-María MacDonald outlines how, after the Mexican-American War of 1846–48 cemented US sovereignty over Texas, “education became contested terrain” as schooling in the newly seized territory came “under the control of American governmental agencies—local, territorial, state, and/or federal.”12 Macdonald points out that while there is a dearth of historical records from the period of Mexico’s ownership of Texas, there is much more material from after 1848, when states such as California, Texas, and Arizona became American territory. 13 This discrepancy, she argues, legitimizes an “American educational history” while erasing a Mexican one.14

While there remains a lack of available resources and research into Mexican American and Hispanic history in the US, a number of historians and researchers are attempting to recover these histories. For example, Monica Perales and Raúl A. Ramos’s 2010 Recovering the Hispanic History of Texas brings together various authors who examine overlooked areas of Hispanic and Mexican American history in the state. Acknowledging that many archives within Texas are sourced from “governmental documents, letters, books, and memoirs of political leaders,”15 Perales and Ramos look to various Chicana/o scholars who instead understand “the value of alternative sources—oral histories, published and unpublished Spanish language writings and periodicals, folklore, photography, and other personal materials” to uncover historical erasures.

The Blackwell School’s museological philosophy emphasizes personal narratives and donated objects, mirroring Perales and Ramos’s focus on first-person accounts. In this way, the museum bridges a gap between historical artifacts and personal memories. It also upholds the museum’s curatorial commitment to self-representation. Not only are its objects donated by former students, but the narratives surrounding the artifacts are authored by them as well. A binder folder on view at the museum collates dozens of written statements by former students, recounting memories from their time at the school. One contribution by Arcadio Nunez Rivera devotes several pages to recalling his elementary school teachers, such as the “stern but loving” Mrs. Rideout, who encouraged him to read a poem at a University Interscholastic League contest—at which he took home first prize. Rivera’s stories are written in direct, unpolished, first-person prose and printed on letter-sized plain paper; no institutional third party has modified or mediated his contribution.

The entrance to the Blackwell School museum. Photo: Tabitha Steinberg, 2023.

A display case in the Blackwell School museum’s main exhibition space. Photo: Tabitha Steinberg, 2023.

The “Unburying Mr. Spanish” exhibit at the Blackwell School museum. Photo: Tabitha Steinberg, 2023.

View of the Blackwell School museum’s main exhibition space. Photo: Tabitha Steinberg, 2023.

A binder of student report cards and other documents on view at the Blackwell School museum. Photo: Tabitha Steinberg, 2023.

The entrance to the Blackwell School museum. Photo: Tabitha Steinberg, 2023.

The museum does not reduce its complex history to one message. The Blackwell School presents the sometimes-unequal treatment of the students at the school alongside happier memories and celebrations of their achievements. In this way, the Blackwell School engages with the complexities of race, segregation, inequality, and identity within the American political and cultural landscape. Similarly, Blackwell’s simultaneous utilization of conventional museum techniques with its own unique approaches continually reforms ideas around assumed and standardized museum practice. Nestled in a corner of the main exhibition room, a waist-high wooden and glass cabinet displays various Blackwell School objects. The display includes donated items such as graduation caps, grade books, Gugu Doporto’s 1963 class ring, and a pair of eyeglasses manufactured in 1951, donated by Maria Rosa Villanaeva Baeza. It also includes a painting of the school by local artist Socorro Munoz, a framed photograph of students from 1932, file binders with articles and memories written by former students, and a tribute to one of the school’s teachers, Willie Harper, a framed letter from Harper thanking the Blackwell Reunion Committee for honoring her at their fourth reunion, and a framed photograph of her.

The exhibit, lo-fi and varied in its methods, is exemplary of the Blackwell School’s display techniques. The repurposed cabinet, formerly used as a school display case, is one of many educational displays utilized for exhibits by the museum. It is reminiscent of exhibits within glass plinths and cabinets at more traditional museums, but here the cabinet formalizes the objects as artifacts without alienating them from their original use and significance. The Blackwell School does not divorce its “museumified” collection from its genuine context. This has the effect of maintaining the artifacts’ everyday quality, and underscores the museum’s community-led approach. We are reminded that the museum was founded by former students whose particular understanding of the collection’s context and history forms a special part of the museum’s conception of cultural preservation and display. Visitors can also flip through the binders themselves, lending a tactile interactivity to the stories of the school.

As Biden’s bill states, the Blackwell Museum’s building provides an authentic setting to engage with its history, functioning both as an artifact in its own right and as a store place for its collection. The museum includes an exhibit dedicated to the history and continued restoration of the building that includes photographs, architectural plans, and building material samples. This creates a unique inversion and doubling. In contrast to the common museological practice of removing objects from their origins and restaging them in foreign, often pseudo-neutral environments, the Blackwell School instead returns their donated objects to their original home.

The museum stands simultaneously as a site where historical materials are preserved and where societal values are shifted. Long neglected by dominant museum discourse, the Blackwell School story of segregated education of Hispanic and Mexican-American children is now firmly embedded within a central institutional body in the United States. So too are its precious objects, each punctuating the story in a unique and significant way. These objects, which until recently were stored and cared for under precarious circumstances, are now ensured safety as they begin a new life held “in perpetuity.”

In a window alcove in the Blackwell School’s front room, a small, altar-like exhibit commemorates the “Burying Mr. Spanish” and “Unburying Mr. Spanish” ceremonies in tandem. Each has its own framed plaque; in keeping with the museum’s instrumentalization of the building’s former furnishings, the “Burying Mr. Spanish” panel rests on a wooden school bench in front of the alcove. Behind it, the “Unburying Mr. Spanish” plaque hangs on the alcove’s back wall; the shovel, small wood coffin, miniature dictionary, and wooden cross used in the latter burial lean have been arranged below it. Just as Blackwell School teacher Evelyn Davis wielded the symbolic power of objects to represent the suppression of the Spanish language, the former students have employed the same tactics to honor, rather than suppress, their histories. Through a symbolic unburying, their heritage was resurrected. This origin story and its artifacts remain one of the Blackwell School’s most powerful exhibits. Though the “Burying” plaque is foregrounded in space, “Unburying” and its relics are positioned above, the clear successors to the Blackwell School’s legacy and stewardship. The message of its arrangement is clear: you buried, we unbury.

Wall text, The Blackwell School, Marfa, Texas.

Wall text, The Blackwell School.

Victoria-María MacDonald, “Hispanic, Latino, Chicano, or ‘Other’?: Deconstructing the Relationship between Historians and Hispanic-American Educational History,” History of Education Quarterly 41, no. 3 (2001): 403.

Wall text, The Blackwell School.

Wall text, The Blackwell School.

Gretel Enck, in discussion with the author, December 2022.

Timothy Mattison, “The State of School Segregation in Texas and the Factors Associated with It” in Texas Education Review (Austin: Texas Education Review, 2020), 29.

Dennis J. Bixler-Marquez, “The Schools of Crystal City: A Chicano Experiment in Change” in Recovering the Hispanic History of Texas, eds. Monica Perales and Raúl A. Ramos (Houston: Pinata Books, 2010), 93.

Timothy Mattison, “The State of School Segregation in Texas and the Factors Associated with It” in Texas Education Review (Austin: Texas Education Review, 2020), 19.

Mattison, “The State of School Segregation in Texas and the Factors Associated with it,” 23.

Gretel Enck, in discussion with the author, December 2022.

MacDonald, “Hispanic, Latino, Chicano, or ‘Other’?,” xi.

MacDonald, “Hispanic, Latino, Chicano, or ‘Other’?,” xi.

MacDonald, “Hispanic, Latino, Chicano, or ‘Other’?,” xi.

Monica Perales and Raúl A. Ramos, “Introduction” in Recovering the Hispanic History of Texas, ed. Perales and Ramos (Houston: Pinata Books, 2010), xi.