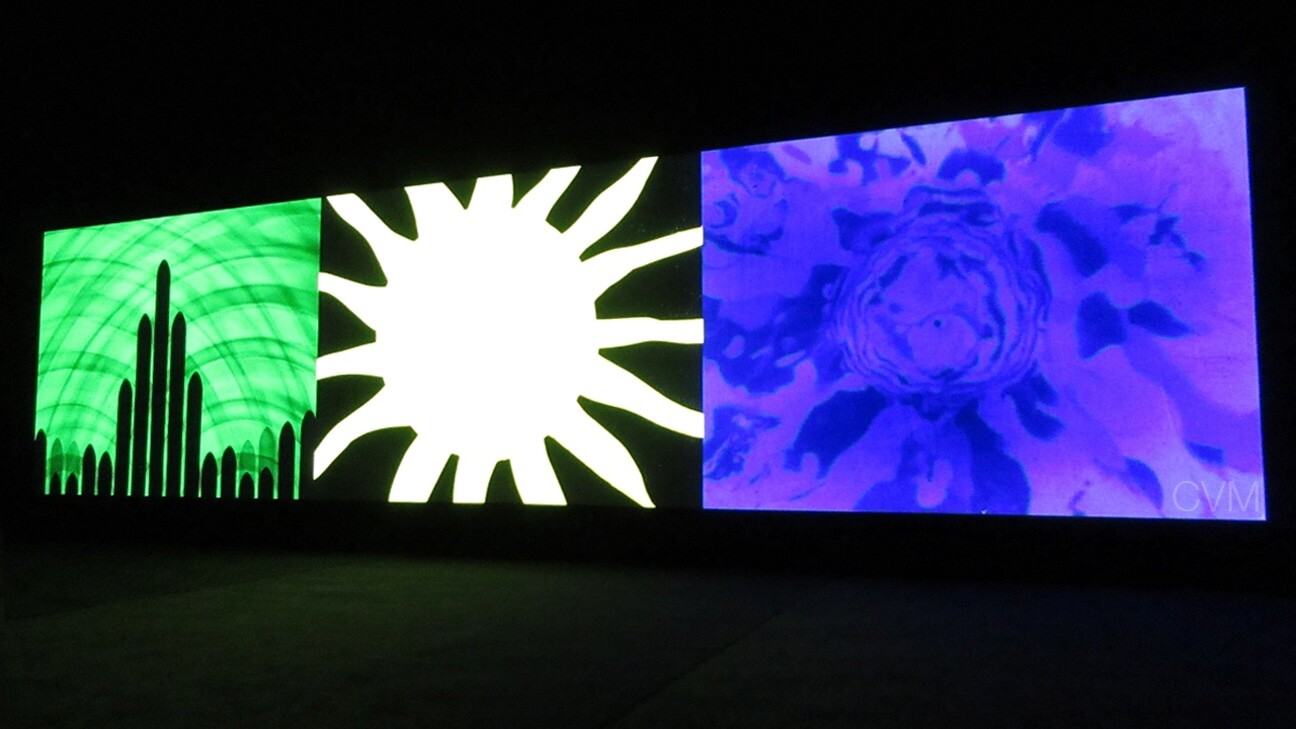

Oskar Fischinger (installation view), Raumlichtkunst, 1926/2012, reconstruction by Center for Visual Music. © Center for Visual Music

On the occasion of the upcoming event Cosmic Cinema: Jordan Belson and the Vortex Concerts, which will take place on Tuesday, March 25 at 7pm at e-flux Screening Room (see more information about the event here), we are publishing a text by Cindy Keefer which traces the early history of immersive cinematic environments in the pioneering work of Oskar Fischinger and Jordan Belson expanding the visual and spatial boundaries of film.1

The origins of immersive media environments, multiple-projector Expanded Cinema performances, and 1960s psychedelic light shows can be traced to the early work of two primary pioneers, Oskar Fischinger and Jordan Belson. These filmmakers expanded their work beyond the rectangular film frame and traditional screens, using multiple cinematic projections in a manner surpassing anything previously attempted. They covered rooms, domes, and planetariums with abstract imagery, generating sophisticated illusions by combining film with other art forms to create a greater experience. Both built their own machines and devices to create their imagery, and both pushed the boundaries of cinema, projection, audience interaction, and consciousness throughout their careers.

Fischinger and Belson created cinematic multimedia events from 1926 to 1959; this essay covers three of these precedents to immersive media environments. In 1926, Fischinger’s multiple-projector shows combined abstract films, colored light projections, painted slides, and music; his unrealized 1944 concept for a half spherical theatre (like a planetarium) called for center film projectors filling the dome. Belson and Henry Jacobs’ late 1950s Vortex Concerts began as concerts, soon accompanied by multiple projection devices across the dome of San Francisco’s Morrison Planetarium.

Fischinger (1900-1967) produced over fifty films and is recognized as the father of Visual Music and the grandfather of music videos, influencing generations of filmmakers, animators, and artists, to the present day. Visual Music is a type of media exploring the correspondences of image and sound (though sometimes silent), as film historian William Moritz wrote, “A music for the eye comparable to the effects of sound for the ear.” Fischinger began his animated film experiments in Germany circa 1920, inventing apparatuses to produce abstract films like his Wax Slicing machine, by which he animated patterns sliced through a block of wax. He produced some of the first and most significant visual music films. Beginning in Munich in March 1926, Fischinger joined Hungarian composer Alexander László for the latter’s Farblichtmusik [Color Light Music] performances, combining Fischinger’s abstract 35mm films with painted glass slides and projected light from László’s color-light piano (an instrument that produced color as the keyboard was played, often with colors tied to specific notes). Music varied from László’s own compositions to Frédéric Chopin, Sergei Rachmaninoff, and Alexander Scriabin. New research indicates Fischinger used only one 35mm film projector in these performances.

László had begun performing Farblichtmusik shows in 1925, though without film. Fischinger later discussed their joint performances and László’s machinery with curator Hilla Rebay of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (now the Guggenheim) in New York. Fischinger wrote:

László’s machine was a technical marvel […] built for him by one of the best and most imaginative engineers […] it was fantastic. It was a giant apparatus, which was played by him and his many assistants. He built in a special film projector for my films, and that topped everything. Zeiss Ikon in Dresden helped him […] it cost unheard of sums of money and was shown in all the opera houses of Europe […] At that time, Zeiss Ikon developed the unique and wonderful planetarium projectors. For that reason, and also because of the publicity connected with it, they were very much interested in László’s Spectrum-Piano [Farblichtklavier] and at that time they put everything at his disposal that he could possibly ask for […]2

Rebay in turn discussed various concepts of “expanded cinema,” color organs, and what we today call immersive cinema with László Moholy-Nagy, Norman McLaren, and Charles Dockum (whom the museum sponsored in the 1940s, along with Fischinger and Belson) and thus appears to have been a link between Fischinger’s 1920s multiple-projector work and later developments in the field. McLaren and Dockum proposed “expanded cinema” and color-light projection concepts to Rebay, though her introduction to the idea was from Fischinger.

In 1926, a Farblichtdome (Color Light Dome) was constructed for Farblichtmusik performances at the Gesolei festival in Düsseldorf. A review in the Westphalian Landeszeitung described the changing light effects in the dome: rising light effects for a Scriabin score; bright red, then yellow, then harsh green colors, followed by blue circles and spirals.

Historian Dr. Jörg Jewanski explains:

From May to October 1926, a huge exhibition took place in Düsseldorf,Germany, named ‘Gesolei’. Nearly 7,500,000 people visited 174 exhibition houses. In No. 78 ‘Light technique,’ László performed his Farblichtmusik: 8–10 performances every day, altogether 1200 performances, shown to more than 40,000 people […] László started his performances at the ‘Gesolei’ on May 22, but first without Fischinger’s films, because there were problems with the fire brigade (nitrate films were flammable and needed special permission).3

A July 1926 review by critic Rudolf Schneider discussed Fischinger’s “wax experiments” footage used in a Farblichtmusik performance: “Fischinger’s idea and invention is a great advance.” The review described some of his other film images: “snakes, fog, balls, rings…fantasy,” and noted that Fischinger was working on a film performance called Fieber. Schneider mentioned this new art “that Fischinger calls Raumlichtkunst.”4

László was not generous in giving Fischinger credit for his work, and yet it appears the press gave more praise to Fischinger’s films than László’s music. The two parted ways later in 1926, and Fischinger began performing his own independent multiple-projector shows called Fieber, Vakuum, and Macht. From newspaper reviews and Fischinger’s notes, we now understand these performances as attempts to create some of the very first cinematic immersive environments.

Fischinger professed his belief that all the arts would merge in a new art he called “Raumlichtmusik.” He wrote of “Eine neue Kunst: Raumlichtmusik” (The new art: Room or Space, of Light and Music): “Of this Art everything is new and yet ancient in its laws and forms. Plastic – Dance – Painting – Music become one. The Master of the new Art forms poetical work in four dimensions […] Cinema was its beginning […] Raumlichtmusik will be its completion.” 5 A critic suggested the name “Raumlichtkunst,” substituting “art” for music.

In October 1926, Schneider again wrote about Fischinger, reporting that he was working on a film for multiple projectors titled Fieber (Fever). A 1927 review of Fischinger’s cinema performance in Munich notes that his current work was called Macht (Power), another is called Fieber, and that a third, titled Vakuum, has been finished and will soon be ready for showing. 6 In December 1927, an article titled “Raumlichtkunst” in Die Zeitlupe München magazine praised Fischinger extensively, describing his three-projector film show, his sliced film technique (wax experiments), and his “original art vision which can only be expressed through film.”

William Moritz later interviewed László, who confirmed he’d seen Fischinger’s solo show in Munich using five 35mm film projectors and slide projectors with painted glass slides. In his 2004 book Optical Poetry: The Life and Work of Oskar Fischinger, Moritz recounts how Fischinger “prepared his own multiple projector shows (including some of the imagery from the László shows) with three side-by-side images cast with three 35mm projectors, slides to frame the triptych, and, at climactic moments, two additional projectors which overlapped the basic triptych with further color effects,” using “all three systems for colorizing (tinting, toning and hand-coloring) to give a wider variety of colors.” 7 No records have been found of performances of these shows by Fischinger after the late 1920s.

Working with Fischinger’s film archive decades later, Moritz found film material that he believed was from these shows and produced a recreation film in 1980. It was an anamorphic triple panel film optically printed onto a single strand of 35mm film, titled R-1, ein Formspiel. In 2009, a full preservation and reconstruction project began with the original nitrates, including some used by Moritz, in Fischinger’s film archive which is now at Center for Visual Music (CVM). The Los Angeles nonprofit archive CVM —of which I am the director—photochemically restored four reels of the 35mm films, restored additional color digitally, and produced a three-projector HD installation titled Raumlichtkunst.8

Endless Space Without Perspective

In the years following the Raumlichtkunst performances, Fischinger became successful in Europe with his abstract animated films, his popular series of Studies shown worldwide, and his waltzing cigarette commercials. Based on the international success of his commercials and colorful animated films, Paramount Studios offered him a job, and with their help, he emigrated to Hollywood in 1936, thus becoming the direct link from the European avant-garde film community to West Coast experimental filmmaking. He worked briefly at Paramount, MGM, for Orson Welles, and at Disney, where he created concept drawings for the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor section of Fantasia (1940), among other work, but was ultimately not successful in the studio system. As an independent artist, the studio committee approach was a challenge; his fluency in English was limited; and when the United States entered World War II Germans were declared “enemy aliens” and unable to work legally.

Rebay and the Museum of Non-Objective Painting provided support for him to make several films in the 1940s. Plans were underway then for the new Guggenheim Museum, with Frank Lloyd Wright spending years working on designs for the new institution. Rebay was interested in creating a Film Center in the museum and discussed it extensively with Fischinger, who was to be its director. Among other plans for this Film Center, in 1944 Fischinger proposed adding a dome theatre in the new museum:

I would like to suggest to you a bigger theatre – half spherical – like a big planetarium. The Machines in the Center. The spheric projection-surface of a planetarium, produces a perfectly clear feeling of endless space, similar to the feeling which produces the star-lit-heaven at night. It is a cosmic-feeling of endless endless space without perspective. Images projected in such a sphere become far distant.

The people (a few hundred) are sitting in a big circle around the projection machines. The Sound comes (ideal) also from the center like the lightbeams of the projectors, and light and soundwaves strike the Sphere and are there reflected to the people, which will understand, maybe with there [sic] third Eye. 9

Fischinger also suggested the audience should recline on their backs, looking up at his abstract films projected onto the dome. Unfortunately, this dome theatre was not built. Fischinger’s relationship with Rebay ended in 1947, and her position at the museum concluded soon after. From then on, Fischinger found little support in America for his film work but continued to experiment with a 3-D stereo film, numerous animation tests, and synthetic sound.

In the late 1940s, he invented the Lumigraph, an analog color-light performance instrument to be played in completely dark rooms to accompany a variety of music. Though he performed it only a few times publicly in Los Angeles and San Francisco, many guests at Fischinger’s home enjoyed shows he gave with his daughter Barbara.

One filmmaker influenced by Fischinger’s abstract films and his Lumigraph was Jordan Belson.

Belson and the Vortex Concerts

Belson (1926-2011) studied painting at the California School of Fine Art (later San Francisco Art Institute) and received his B.A. in Fine Arts from the University of California, Berkeley in 1946. At the historic Art in Cinema series at San Francisco Museum of Art, which began the same year he graduated, he saw films by Fischinger, Norman McLaren, Hans Richter, and others that influenced his work. Belson’s first two films were shown at later Art in Cinema screenings and briefly distributed, though Belson considered himself primarily a painter. After seeing Belson’s work, Fischinger recommended Belson to Rebay for a grant from the Museum of Non-Objective Painting. They met several times, including in San Francisco during the Art in Cinema series.

In 1953, Belson attended a screening of Fischinger’s films at the San Francisco Museum of Art that was followed by a live performance by the filmmaker on his Lumigraph. Belson later remembered the performance in the completely blackened auditorium:

In mysterious synchronization with the sounds appeared soft, glowing images […] These irregular, always-changing shapes could flicker and pulsate, and when they swirled around, they could leave a vague trail like a comet’s tail […] Sometimes the lights would disappear and appear suddenly, but other times they would fade in and out extremely slowly – just as one color might glow exquisitely in saturated duration or suddenly jump to another hue, with brilliant, tasteful timing.” 10

He also recalled how Fischinger “could turn even the simplest things into a luxurious, magical illusion of cosmic elegance. That was very inspirational to me.” 11 Four years after his transformative experience at San Francisco Museum of Art, Belson would create his own cosmically elegant illusions at the Vortex Concerts.

On May 28, 1957, the first of the legendary Vortex Concerts was held at the California Academy of Science’s Morrison Planetarium in San Francisco. Featuring new music from international avant-garde composers curated by sound artist Henry Jacobs, Vortex was, in the words of Belson, its Visual Director, “a series of electronic music concerts illuminated by various visual effects.” Initially sponsored by Berkeley radio station KPFA and the California Academy of Sciences, five different Vortex series were held at Morrison through January 1959, with over thirty-five total performances. 12

Jacobs played musique concrète and electronic music from composers including Karlheinz Stockhausen, Henk Badings, Gordon Longfellow, and David Talcott, plus his own compositions. In the blackness of the planetarium’s sixty-five-foot-wide foot dome, Belson created spectacular illusions with abstract patterns, lighting effects, and cosmic imagery. He recalled “working in an environment representing the heavens […] a full-bodied experience with stunning visual effects.” 13

The program notes for the fourth series describe:

Vortex is a new form of theater based on the combination of electronics, optics and architecture. Its purpose is to reach an audience as a pure theater appealing directly to the senses. The elements of Vortex are sound, light, color, and movement in their most comprehensive theatrical expression. These audio-visual combinations are presented in a circular, domed theater equipped with special projectors and sound systems. In Vortex there is no separation of audience and stage or screen; the entire domed area becomes a living theater of sound and light.

The planetarium’s sophisticated sound system had thirty-eight speakers in a circular configuration, and an electronics expert constructed a rotary mechanism with a handle so that Jacobs could “whirl” the sound around the room to achieve what was called the Vortex Effect. The Vortex III program explained: “The name – Vortex – is derived from the ability to move the sound around the dome in either clockwise or counterclockwise rotation, at any speed. Since a single program source is used this is not a stereophonic sound but an entirely new aural experience.” 14

Vortex became immediately popular. The attendance exceeded all expectations, though from the beginning Morrison’s management had difficulty with some of the “bohemian” attendees. The press loved Vortex and continually showered the series with praise. This type of immersive environment had never been created before with experimental music and imagery. Vortex 4 program notes described its potential “for directly reaching an audience with unique sensory experiences.” Decades later, Belson remembered how “you could create some beautiful and terrifying sensations and feelings there.”15

As Vortex continued, the sophistication of the visual effects increased. A major San Francisco art critic Alfred Frankenstein wrote, “Geometrically abstract forms, painted on slides and projected through slowly twirling prisms onto the apex of the dome, go through various spatial evolutions.” 16 Belson could utilize up to thirty projection devices (though not all at once), including the planetarium’s thirteen-foot starfield projector, kaleidoscope, rotating and “zoomer” projectors, strobes, slide projectors, rotating prisms, 16mm film projector, a flicker machine, a spiral generator, and four interference pattern projectors created especially for Vortex. The Vortex V program notes claimed that “Vortex utilizes all known systems of projection.” Belson was clear that the use of 16mm film footage was limited, and no complete films were screened in the San Francisco concerts. When brief 16mm excerpts and fragments were used, he mixed them with the planetarium’s cosmic imagery, color effects, stencils, and patterns. Though several of Belson’s abstract films were born from Vortex experiments, including Allures (1961) and Séance (1959), they weren’t shown at the concerts. Nor, contrary to myth, were James Whitney’s Yantra (1957, completed with sound 1959) or Hy Hirsh’s Eneri (1953), though a few manipulated black and white shots from an early version of Yantra were in Vortex V. A 1961 article in Film Quarterly described the show:

The visual images […] consist of non-objective symmetrical patterns which move and change, expand and contract; of color effects and black-and-white effects; of fade-ins and fade-outs; occasionally of the planetarium effects themselves – stars and comets; and of combinations of all these. The images are projected by a dozen specialized devices, among them a standard film projector (though the audience does not get the feeling of a film on a screen, nor does it hear any sounds of machinery working) […] The combination of space, light, color, and sound creates an enveloping audio-visual experience in a completely controlled environment. 17

Belson created illusions of floating in space. He explained that no images touched the edges, no frame lines were ever visible, and there were never frames of reference. In his words:“Just being able to control the darkness was very important. We could get it down to jet black, and then take it down another twenty-five degrees lower than that, so you really got that sinking-in feeling […] we were able to project images over the entire dome, so that things would come pouring down from the center, sliding along the walls. At times the whole place would seem to reel.”18

In January 1959, Frankenstein reviewed a Vortex performance in the San Francisco Chronicle, describing what he saw as “geometric patterns of great purity and simplicity moving slowly in the center of the darkened dome, and vertiginously rapid forms of white light that streak and reel all over the planetarium’s immensity” and praising how “one of [Belson’s] visual compositions has the extraordinary effect of lifting the spectator right off his seat to traverse that sky-space in a wonderfully disembodied way.”

Belson and Jacobs also performed several Vortex Concerts in a simple planetarium at 1958 Brussels World’s Fair, commonly known as Expo 58. A Time magazine article in February 1959 praised Vortex, discussing its popularity and the Brussels shows.

Though the concerts were enormously popular, attracting capacity audiences and long lines, friction with planetarium management increased over the course of their run until Vortex was cancelled. The final series, Vortex V, was in January 1959. Belson invited animator John Whitney Sr. to contribute some of his pendulum patterns; though John did not participate, his brother James supplied some footage and attended a rehearsal. Meanwhile, Jacobs worked on a “Highlights of Vortex” LP that was released later that year on Folkways Records. Its liner notes called Vortex “Entertainment for the Space Age” and stated that “plans are afoot for a Vortex performance in Japan, as well as performances in Europe,” but further performances of Vortex by Jacobs and Belson in a planetarium never occurred.

In October 1959, a very different event called Vortex Presents, billed as “a concert of electronic music and non-objective film,” was staged by Jacobs and Belson at the San Francisco Museum of Art. Using a single 16mm projector, short films were projected to accompany taped music. This marked the first synchronization and screening of James Whitney’s film Yantra with a soundtrack by Henk Badings and included an early version of a Belson film later completed as Allures. The audience’s disappointment with Vortex Presents turned the planned series into a single night; according to Belson, they expected a Vortex Concert like the planetarium show but instead saw a film screening.

Four decades later, Belson referred to the Vortex Concerts as “a sacred memory,” not possible or desirable to be re-created. He continued to create a remarkable oeuvre of over thirty abstract films richly woven with cosmological imagery exploring consciousness, transcendence, and the nature of light itself. Today, his films are featured in international museum exhibitions; and his last film, Epilogue (2005), was funded by the NASA Art Program.19

In 1979, Moritz wrote that Vortex “established the tradition of the psychedelic multiple-projector light show which blossomed in the late 60s.” 20 While it’s true that some 1960s light show pioneers in San Francisco attended Vortex (for example, Tony Martin, who created many Fillmore shows), today we know these roots lie further back, in the 1920s. Fischinger’s multiple-projector performances are the direct precursor to light shows and are likely the first immersive environments using cinema.

In 1959, the Vortex Presents notes stated that “the future seems to hold great promise for this new combined art form with the advent of further developments of the cathode-ray tube and video-tape. There have already been musical scores composed by analogue computers and ossilliscope [sic] visualizations of thought patterns. The separated worlds of Science and Art are ever reaching closer together.” 21 Today those worlds are even closer and continue to merge, especially in abstract media influenced by Fischinger and Belson’s work.

© Cindy Keefer

An earlier version of this essay was originally published in Leonardo Electronic Almanac, Creative Data Special Issue, vol 16, no 6–7. MIT Press/The International Society for the Arts, Sciences and Technology, October 2009.

Fischinger to Hilla Rebay, June 28, 1942. Quoted in English in Joan M. Lukach, Hilla Rebay: In Search of the Spirit in Art (New York: George Braziller, Inc., 1983), 223–24.

Dr. Jörg Jewanski, email to the author, May 29, 2005. Though planned, it’s unknown if Fischinger’s films were finally allowed in the performances. For more on László, see Jewanski and Natalia Sidler, eds., Farbe – Licht – Musik: Synaesthesie und Farblichtmusik, (Zurich: Peter Lang, 2006).

Rudolf Schneider, “Formspiel durch Kino,” Frankfurter Zeitung, July 12, 1926.

Oskar Fischinger, “Raumlichtmusik.” Unpublished typescript, n.d. Fischinger Collection, Center for Visual Music, Los Angeles. Fischinger’s original papers are owned by CVM.

Walter Terven, “Bei Fischinger in München,” Film Kurier, January 15, 1927.

William Moritz, Optical Poetry: The Life and Work of Oskar Fischinger (Eastleigh, UK: John Libbey Publishing, 2004), 12.

The Raumlichtkunst photochemical film restoration was done by CVM with the support of an Avant-Garde Masters Grant from the Film Foundation, administered by the National Film Preservation Foundation. The digitization, digital color restoration, and reconstruction were not funded by grants. The Raumlichtkunst reconstruction premiered in June 2012 as a black box installation at Tate Modern, London, and the Whitney Museum, New York. For more info, see http://www.centerforvisualmusic.org/Raumlichtkunst.html

Letter, Oskar Fischinger to Hilla Rebay, April 25, 1944. Fischinger Collection, Center for Visual Music, Los Angeles.

Jordan Belson, 1971 testimonial statement about Oskar Fischinger, cited in Moritz, Optical Poetry, 169.

ibid.

The author thanks Jordan Belson for sharing his time to discuss Vortex. Some information here is derived from conversations and correspondence with Belson between 2002–2011. Thanks also to Catherine Heinrich. In 2008, Belson remembered there were only a few dozen concerts. No documentation exists to support the statements of “over 100 concerts” in several texts. From existing documentation, it is possible to verify thirty-six concerts, including Brussels, without counting a few of the unscheduled performances; an exact count is difficult as Belson confirmed occasionally a third performance was given when only 2 were scheduled. Though several texts (Renan, Polt) from the 1960s refer to about sixty concerts, and later texts (Youngblood, Moritz) refer to one hundred concerts, Belson does not support these counts, nor do documents, press and programs from 1957–59.

Jordan Belson, telephone conversation with the author, December 2002.

Vortex III Program Notes, January 1958. The “electronics expert” was Alvin Gundred of the planetarium, according to Henry Jacobs (interview with author, February 2014). Elsewhere, a “Stanford engineer” is credited.

Belson, cited in Scott MacDonald, “Jordan Belson,” A Critical Cinema 3: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 75.

Alfred Frankenstein, “Vortex: The Music of the Hemispheres,” High Fidelity & audiocraft 9.5 (May 1959).

Harriet R. Polt and Roger Sandall, “Outside the Frame,” Film Quarterly 14.3 (Spring, 1961), 35-36.

Belson, cited in Gene Youngblood, Expanded Cinema (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co. Inc., 1970), 389.

Epilogue can be seen on the DVD Jordan Belson: 5 Essential Films, released in 2007 by CVM (http://www.centerforvisualmusic.org).

William Moritz, “Non-Objective Film: the Second Generation” in Film as Film: Formal Experiment in Film, 1910–1975 (London: Hayward Gallery and Arts Council of Great Britain, 1979).

Vortex Presents program notes, October 31, 1959, Audio-Visual Research Foundation, Sausalito, CA.