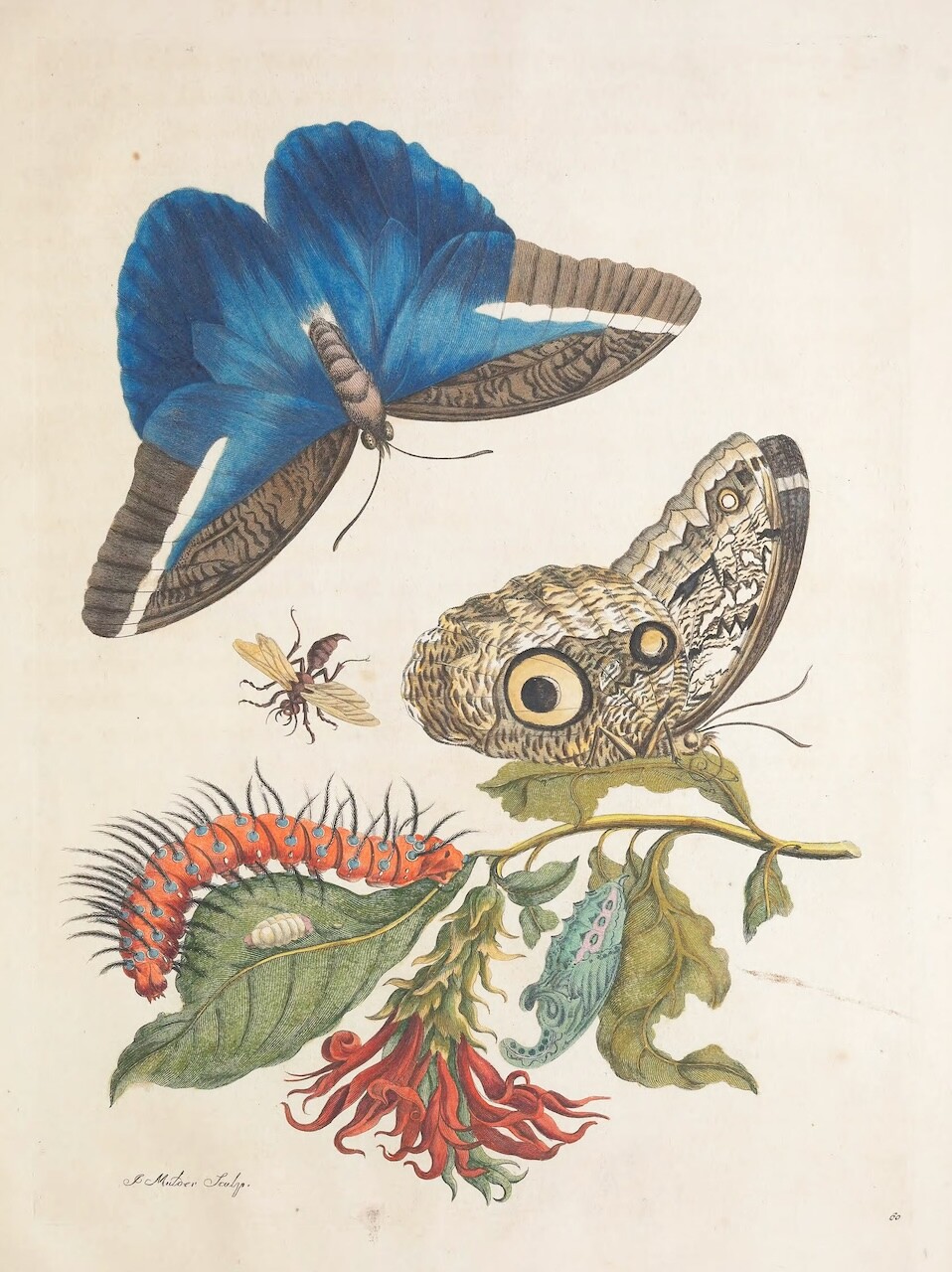

From Maria Sibylla Merian, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (1705).

This is a lightly edited excerpt from Peter Szendy’s For An Ecology of Images, translated by Marco Roth, published by Verso.

Can we—must we—put under the sign of an ecology of images our effort to exit the sphere of an anthropocentric iconomy [a portmanteau of “icon” and “economy]? If it’s the case, ever since Haeckel coined the term, that an ecology is first of all a “natural economy,” don’t we always risk “smuggling” in an anthropocentrism that we would have preferred to leave out? In speaking about an ecology of images, aren’t we making a prejudicial judgment about the value that images in general have for us? In fact, I’m going to try to defend a different way of thinking: the image as a heterochronicity, that is, as a differential of speeds.

But we should already be asking ourselves: When we speak about an ecology of images, when we use that phrase, what legacy comes with it? Where do these words come from? I only know of a few recent and rare occurrences of the expression, mere suggestions that do not really rise to a level that would constitute a field of inquiry in its own right. Susan Sontag was the first, to my knowledge, to advance the idea of “an ecology not only of real things but of images as well.”1 These are the last lines of her 1977 essay on photography. So we are left in suspense. From the preceding paragraphs, we can infer that an ecology of images would be called upon as an antidote to the consumerist logic of an infinite surplus of pictures (“we need still more images; and still more,” Sontag writes). This antidote is said to be necessary even if images aren’t threatened with extinction or exhaustion, even though—or rather precisely because—their reserves are unlimited: “Just because they are an unlimited resource, one that cannot be exhausted by consumerist waste, there is all the more reason to apply the conservationist remedy.” But when Sontag returns to this same idea one year before her death and repeats the same phrase in Regarding the Pain of Others, when she asserts that we are “flooded” in images “that once used to shock and arouse indignation,” when she laments that “compassion, stretched to its limits, is going numb,” she then concludes categorically that there will never be an ecology of images, that no one can ration horror or “keep fresh its ability to shock.”2 In short, the very idea of conservation applied to images is without hope.

In 1992, between the belated birth of the idea of an ecology of images and its precipitous obsequies, the sociologist Andrew Ross tried to grow the seed Sontag had planted. In an essay titled, in fact, “The Ecology of Images,” his attention is drawn to images of the first Gulf War, particularly to pictures of the oil spills in the Persian Gulf. These spills were strategic, an attempt by Iraqi forces to forestall an American amphibious assault. But it was also a propaganda war—a war of images—that they unleashed: in the American press, CNN leading the charge, the military and environmental threats kept getting mixed up or superimposed, the dark tides of oil often an implicit figuration of “the sinister and inexorable spread of Islam/Arab nationalism.”3 Ross then proposes to distinguish between “images of ecology” and an “ecology of images,” so as better to consider how these might interact. The former, he writes, constitute “a genre of images,” comprised of well-known clichés:

on the one hand, belching smokestacks, seabirds mired in petrochemical sludge, fish floating belly up, traffic jams in Los Angeles and Mexico City, and clear cut forests; on the other hand, the redemptive repertoire of pastoral imagery, crowned by the ultimate global spectacle, the fragile, vulnerable ball of spaceship Earth.

After having listed these “images of ecology,” Ross then wonders what an ecology of images might be, “whether images have an ecology in their own right.” This leads him to consider “the social and industrial organization of images,” to consider how “images are produced, distributed, and used in modern electronic culture.”4

Here Ross subjects Sontag’s earlier proposition to a piercing critique. By deploring the “image overload in our modern information society,” by accusing the proliferation of pictures of “depleting reality,” Sontag doesn’t take into account those cases where it’s pre- cisely the images themselves that allow us to struggle against “the material disappearance of the real” and help “counteract the destruction of the natural world.”5 In other words, if Sontag’s proposition is ultimately “disappointing,” as Ross says, it’s because she concedes too much to the commonplace of a “surfeit of information” and thus blocks the possibility that images themselves might prove resistant to their effects. Retrospectively, in light of more recent work, we can say that the critical debate between Ross and Sontag is about the ecology of attention.6

Over the course of his case for the activist power of images of ecology, Ross mentions in passing “the chemical underpinnings of the film economy.” In this way, he opens up another perspective on the ecology of images: that of the direct environmental impact of their production and circulation on a large scale. A number of recent works have confirmed how much the supposedly immaterial universe of digital images formatted as JPEGs or MP4s has an alarming material, ecological, and geopolitical impact. Data centers and server farms must be air-conditioned; cables destabilize the ecosystems through which they run; recycling screens and devices leaves toxic by-products; the extraction of metals necessary for batteries diverts or contaminates freshwater supplies and destroys the ocean depths while also exacerbating the dynamics of neocolonial exploitation. If we are to develop Andrew Ross’s intuition, the project of an ecology of images needs to go further than the images of black tides (like those during the Gulf War) or the unceasing luminescent tide of digital images, and take account of “deep time”—what Jussi Parikka calls a “geology” or “geophysics” of media: the contemporary iconomy would be impossible without metals and metalloids such as lithium for batteries, indium for liquid crystal screens, and germanium for fiberoptics.7

The Mycelium of Iconogenesis

Among these different perspectives that converge toward or diverge from the project of an ecology of images, there is one that remains relatively unexplored: the deep time and duration proper to images produced by what we might provisionally think of as “nature”—without asking too many questions about that word for the moment. Take as an example the pattern and figures that appear on butterfly wings. The temporality in question here belongs neither to the relatively short period of manmade images—whether by hand or by analog then digital machines—nor is it part of deep mineral time, the eras of geologic accumulation of raw materials (metals and fossil fuels) necessary for the industrial and postindustrial circulation of those manmade images. The long unfolding and duration of the image that I’d like to explore in several of its aspects is more about the natural formation of images between, among, and from themselves. I’d like to clear a path for a general iconomy that would ultimately resonate with the governing idea of a deep ecology.8

In order to approach the question of long-term iconogenesis, let us first turn to the remarkable posthumous work of Gilbert Simondon, Imagination and Invention, a series of lecture courses he gave at the Sorbonne in 1965 and1966. Already in his “preamble,” the argument is at once restrained and enlarged in accordance with a paradoxical double move that creates all the interest, contains all the tension, and constitutes the tone of the entire Simondonian project: “A mental image,” he writes, “is a relatively independent subset within the living being qua subject [être vivant sujet].”9 It is not therefore a question of images in general; the course limits itself to dealing with an enclave of images contained within a living being. But—and here’s the enlargement that counterbalances the restriction—he attributes a relative independence to this enclave of images. Put another way, we can say that the realm of mental images we contain could very well overflow the container; it could reveal itself to be larger and vaster than the image repository that we ourselves are, we the living (and it’s not for nothing that Simondon voluntarily leaves open the question of knowing whether this “living being” and bearer of images must be human).

And here we reach the decisive turn in Simondon’s argument: this autonomous but also overflowing enclave of “the mental image” (the work of the “reproductive imagination”) does not exist only as a simple collection and storehouse of accumulated images. It obeys its own cyclic rhythms, a “cycle of images” that goes through successive “phases” that constitute “a single process of genesis, comparable in its unfolding to the other genetic processes that the living world shows us (both phylogenesis and ontogenesis).”10 What Simondon attempts to show is not only how living beings make—or allow to bloom—within themselves those images that traverse and also reciprocally form them but, above all, how these images themselves result from transformations and metamorphoses whose laws are analogues to those of the evolution of living species (phylogenesis) or of individuals (ontogenesis).

To speak of “a mental image” when referring to these mobile and cyclic pictorial formations that blossom and wither within us living beings is to use a vocabulary that may be misleading—all the more because Simondon himself notes that the “mental content of which we can be conscious” results from “cases of an almost exceptional surfacing [affleurement].” Then, using a mycelial metaphor, Simondon further suggests that what’s of importance to iconogenesis over the long term is less “the visible part of the mushroom”—that is, those images that emerge in conscious life—than the “infrastructure that carries them along,” namely the “mycelium,” that ensemble of buried filaments that, without ever appearing aboveground, nonetheless “proliferates.”11

If the preamble to Imagination and Invention is placed initially under the sign of the mental image as it exists “within the living being qua subject,” it nevertheless quickly becomes clear that the image in question is also, and above all, that which “refuses to let the subject’s will direct it, and presents itself according to its own forces, living in our consciousness like an intruder disturbing the order of a household.”12 Iconogenesis obeys its own laws while passing through the subject, and parasitizing it.

Simondon here recalls “the most rationalist of the ancient philosophers,” those who swore by the materialism of images, like Lucretius, who in his De rerum natura explains the formation of images from simulacra—that is, membranes or bark (membranae vel cortex) that detach from things. Far from sweeping this away as a curiosity of interest only to intellectual historians of antiquity, Simondon understands the Lucretian theory (which is to say the Epicurean theory) about the “physical causes” of the image as one more confirmation of its “potent exteriority and relative independence … with respect to the subject.”13 The image’s status, he says, is that of a “quasi-organism,” a virus or a guest parasite, “inhabiting the subject and developing within it.”

Simondon initially multiplies analogies in his attempt to grasp this materiality and viral reproducibility of the image: it is “endowed with a ghostly power”—it “overcomes the subject,” it insinuates itself “as we say a ghost can walk through walls,” and it ends up “like a foreign population in the midst of an orderly state.” But in order to translate the mobile density of images—since “each image has a weight, a certain force”—these comparisons to spectral forms or immigrant populations soon give way to what will remain the central and dominant paradigm of the discourse of iconogenesis: that of the living organism.14 Simondon resorts constantly to this, in particular in the following crucial passage:

Studies of ontogenesis have shown that growth processes do not cover the organs and functional systems of a living being in a uniform way: there are lags in each partial growth relative to the others, and there are different speeds, especially among complex organisms, so much so that it is difficult to establish the exact moment at which an organism reaches its complete adult stage; moreover, growth and development display stages and cycles, separated by periods of transition in which a dedifferentiation is followed by a reorganization … Mental images … would thus possess a genetic dynamism analogous to that of an organ or a system of organs on a trajectory of growth.15

For all intents and purposes, the image behaves like an organism, says Simondon. And this passage is crucial to what interests me here since, by proposing an analogy between ontogenesis (the development and growth of an individual) and what I continue to call iconogenesis (the “genetic dynamism” of images),16 Simondon—as we’ve just read—emphasizes the differences in phase or the differentials of speed at work in them, images and organisms both.

Susan Sontag, On Photography (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1977), 180.

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2003), 108.

Andrew Ross, “The Ecology of Images,” in Eloquent Obsessions: Writing Cultural Criticism, ed. Marianna Torgovnick (Duke University Press, 1994), 187.

Ross, “The Ecology of Images,” 190.

Ross, “The Ecology of Images,” 197.

See Yves Citton’s remarkable synthesis devoted to this question, The Ecology of Attention, trans. Barnaby Norman (Polity Press, 2017).

Jussi Parikka, A Geology of Media (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), esp. 52, where the author takes care to distinguish his approach from that of the media archeologist Siegfried Zielinski, who also refers to “deep time” but means by that the complex protohistory of modern media such as it appears already with, for example, “medieval alchemists.” For his part, Parikka makes the case for “an alternative deep time” that encompasses “a geophysics of media culture.” For an overview of the ecological risks of contemporary media, see Sean Cubitt, Finite Media: Environmental Implications of Digital Technologies (Duke University Press, 2017).

As sketched out by Arne Naess in “The Shallow and the Deep, Long-Range Ecology Movement,” Inquiry: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy 16, no. 1 (1973).

Gilbert Simondon, Imagination and Invention (University of Minnesota Press, 2023), 3.

Simondon, Imagination and Invention, 3–4.

Simondon, Imagination and Invention, 4.

Simondon, Imagination and Invention, 7, emphasis added.

Simondon, Imagination and Invention, 8–9, translation modified.

Simondon, Imagination and Invention, 8–10.

Simondon, Imagination and Invention, 18.

In his short but excellent summary, Emmanuel Alloa proposes the term “eikogenesis.” Emmanuel Alloa, “Prégnances du devenir: Simondon et les images,” Critique, no. 816 (2015), 370.