February 15–May 4, 2025

For the first time, the Hawaiʻi Triennial boasts an ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi title which stands alone with no English translation. Yet aloha, which here serves as a marker of cultural specificity, is also among the most globally familiar—that is to say, decontextualized and commodified—Hawaiian words. In Hawaiian, nō is as an intensifying particle akin to “very” or “strongly” which, when glossed in English, reads as a statement of negation. Curators Noelle M.K.Y. Kahanu, Wassan Al-Khudhairi, and Binna Choi thereby juxtapose understandings of aloha as love, generosity, and reciprocity against the possibilities created by defiance and refusal. They urge their audience to renew the potency of a word routinely taken for granted by Hawaiʻi residents and tourists alike, framing Hawaiʻi as a site where aloha is regenerated through artistic practices beyond its dereliction at the hands of a militouristic occupying state.1

The destruction of Lahaina in the 2023 Maui wildfires weighs heavily on the exhibition. In a moving display of inter-island solidarity, works speaking to this context are found on all the participating islands in the triennial: Oʻahu, Maui, and the Big Island (Hawaiʻi Island). Hale Hoʻikeʻike at the Bailey House in Wailuku features filmmakers Sancia Miala Shiba Nash and Noah Keone Viernes’s Hōʻale (2025), a short documentary about Keʻeaumoku Kapu, a Kanaka ʻŌiwi community leader and activist. Kapu fought for decades to reclaim his kuleana land in Kauaʻula Valley (above Launiupoko in Maui Komohana, near Lahaina town) from West Maui Land, a large landowner.2 As he explains the complex legal frameworks that govern land tenure in Hawaiʻi, 3D renderings of the valley with historical map overlays visualize the land claims he eventually successfully affirmed his title to in court. Today, Kapu is extensively involved with mutual aid and recovery planning efforts in Lahaina, and his battle resonates with its residents’ struggles to remain on their land as the town prepares to rebuild.

Pasted to the walls surrounding Hōʻale with a tactile excess of drippy glue, Lieko Shiga’s haunting photo mural Where that Night Leads (2022) tells another story of retrieval, of a mysterious man who collects and cares for tsunami debris in the wake of the March 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, also known as 3/11. Her photographs are borne out of a long, committed engagement with villagers along the Miyagi coast of Tōhoku, staging a phantasmagorical interplay between their residual traumas and memories of the tsunami and their folk traditions and beliefs. At the Triennial’s main hub in downtown Honolulu (located on two floors of an office building) and at the East Hawaiʻi Cultural Center in Hilo, selections from her photo series “Rasen Kaigan” (2012) confront viewers with another example of art that strikingly affirms the power and rawness of life, and the ʻāina that sustains it, in the face of so much loss.3 The curators astutely show that the experiences of artists in Japan after 3/11 can speak to artists in Hawaiʻi seeking to responsibly work with disaster-stricken communities now and into the future.

Shiga’s work raises the question of how Hawaiʻi’s artists might themselves steward memories of the Lahaina fire and the process of recovery. Tiare Ribeaux, who creates wearable art objects that evoke what it’s like to live through ecological collapse, offers an answer in her video installation at O‘ahu’s Bishop Museum. Hoʻōla ka wai iā Maui—He Moemoeā (Water Returns Life to Maui—A Dream) (2025) depicts performers in dresses designed by Ribeaux (used in the installation as projection surfaces) that personify them as water spirits returning to dry and channelized streambeds across Maui. Their dances act as a mythic parallel to the film’s other narrative, which focuses on scientists cleaning up Lahaina’s contaminated soils through bioremediation. Like Shiga, Ribeaux proposes that we create our own legends and folktales about the disaster, which can be safeguarded in our bodies and transmitted through generations.

Despite how thoughtful these artworks were, I had a lingering sense that something was left unaddressed. In a recent article the curator Eimi Tagore noted that, after 3/11, artists in Japan were instrumentalized by state-sponsored festivals which promoted the artist-catalyzed revitalization of devastated rural areas through tourism.4 Over time, these initiatives had the effect of stifling dissent against government policies, projecting a falsely harmonious image of artists and communities quickly “moving on together” from tragedy. While Japan and the US have different approaches to disaster recovery, the similarities here gave me pause. Shiga’s brooding and shadowy images, which use the rubble and refuse left behind from reconstruction projects as props, do communicate some of the bitterness and resentment that villagers in Japan felt. But I wished the triennial had more deeply considered how this phenomenon might manifest in the specific context of Hawaiʻi, and how it could avoid being instrumentalized in the same way.

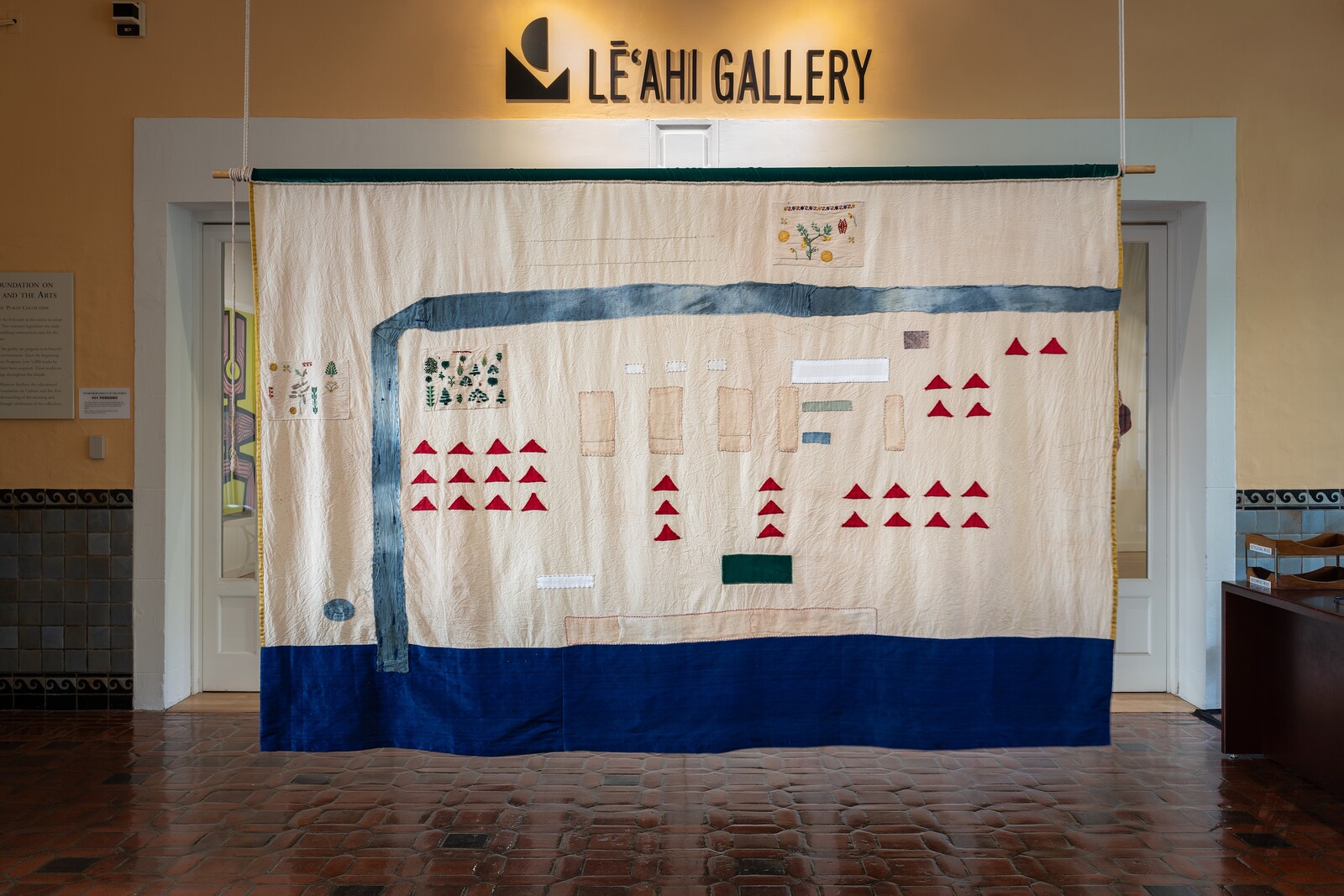

The triennial’s forthright engagement with Palestinian political thought provided the most galvanizing exploration of its themes. Jumana Manna’s “Your Time Passes And Mine Has No Ends” (2025) consists of a series of large banners installed in the second-floor foyer of Hawaiʻi’s state art museum, Capitol Modern. Quilt-like in appearance, they reference handmade flags used in precolonial celebrations in Palestine and are emblazoned with quotes from Palestinian prisoners: a demonstration of unity and rejection of captivity that tears open colonial time.

That such a piece is being prominently displayed in a state art museum (that is also an active government office) next to our capitol building is an impressive achievement in the current US political climate, even in a relatively liberal state like Hawaiʻi.5 It owes much to the Hawaiian sovereignty movement’s strength in creating a platform for artworks like these by mainstreaming discourses of national liberation into local politics. The student movement for Palestine was also honored during a time of great repression against college protesters and activists. Members and affiliates of the University of Hawaiʻi chapter of Students and Faculty for Justice in Palestine participated in workshops led by Manna and in the gallery opening at Capitol Modern, at which they read writings by Palestinians Layan Kayed and Walid Daqqa, both of whom were incarcerated by Israel.

Also on view at Capitol Modern is wendelien van oldenborgh’s Reading Group (2025), a film borne out of reading groups initiated by the artist in independent bookstores that have served as a refuge for radical thought: Hopscotch Reading Room and Khan Aljanub in Berlin, and Native Books in Honolulu. The film’s perspective shifts between the three bookstores over a day-night cycle, their interior light and mood changing as the hours pass. Posted on their walls are quotes from two texts, Nasser Abourahme’s 2021 essay “Revolution after Revolution,” and Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio’s 2024 presentation E Mau Ke Ea: Sovereignty, Sanctuary, and Collective Liberation. Both rethink the meaning of sovereignty, approaching anti-colonial resistance not as the instantiation of a bordered nation-state in our current, immensely cruel world order, but as a “line of flight” which agitates against that same world order to practice ways of organizing and solidarizing beyond the nation-state form. Pamphlets, books, pens, and highlighters are strewn across tables, but no one is seated at them. The absence of people in the bookstores evokes apprehension—in the case of the Berlin locations, we become aware of the suffocating and surveilling force of the country’s Staatsräson. But perhaps this does not mark an absence so much as a transference of presence. What if the unseen reading groups have just left to take to the streets together, transforming theory into practice?

Reading Group restores a revolutionary impulse to everyday time, showing what Palestinians and Hawaiians can draw from each other’s persistence amidst the pitfalls of state capture. It is tucked away in a dim, inconspicuous alcove marked by a single poster bearing the film’s title and credits. Its separation turns it into a puʻuhonua of sorts, like the bookstores in the film: here is a space to sit in pō, to stretch, rest, think, and begin again.6 A space to turn over the words we use to free ourselves and others, to recharge their potentials, re-weight their meanings.7 Like the rest of the triennial, van oldenborgh’s film is a stirring gesture against futility.

Mahalo piha to Chase Tokutaro for his assistance with this article.

Teresia Teaiwa coined the term “militourism” to describe “a phenomenon by which military or paramilitary force ensures the smooth running of a tourist industry, and that same tourist industry masks the military force behind it.” See Teresia Teaiwa, “Reading Paul Gauguin’s Noa Noa with Epeli Hauʻofa’s Kisses in the Nederends: Militourism, Feminism, and the ‘Polynesian’ Body,” in Inside Out: Literature, Cultural Politics, and Identity in The New Pacific, eds. Vilsoni Hereniko and Rob Wilson (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999), 249–263; https://www2.hawaii.edu/~noenoe/Teaiwa.reading.pdf.

Kuleana means responsibility, right, privilege. Kuleana land refers to land granted to Hawaiians under the Kuleana Act of 1850, instituted by the Hawaiian Kingdom during a time when it was transitioning to a European-style model of private property ownership based on allodial title. Various landowners in Hawaiʻi have notoriously attempted to deny ambiguous and unclearly documented titles as a means of acquiring ancestral lands belonging to Hawaiian families.

ʻĀina translates as land or earth.

Eimi Tagore, “Art festivals in Japan: Fueling revitalization, tourism, and self-censorship,” Contemporary Japan 36, no. 1 (2024): 7–19.

Over email, the artist told me that this piece developed out of ideas and research she had begun for a planned show at the Heidelberger Kunstverein in Germany, but which was canceled by the museum a month before it was set to open in November 2023. For more information on that canceled show, see Kerstin Stakemeier, “Ruined Sense/s: Jumana Manna at Heidelberger Kunstverein, an Exhibition That Wasn’t,” Mousse (February 27, 2024), https://www.moussemagazine.it/magazine/jumana-manna-kerstin-stakemeier-heidelberger-kunstverein-2024/.

Puʻuhonua translates as sanctuary, place of refuge; pō as darkness, the shifting night of divine creation.

I’m reminded of an essay by Palestinian author Adania Shibli, in which she describes returning to words after a period of writer’s block triggered when the IDF threatened her family. Waking suddenly one night months later, she greets the objects in her bedroom not in fear, but with aloha: “The faint light emanating from the streetlamps outside, has cast the shadow of the books on the opposite wall, creating that massive black cube shape. Perhaps words are like this. They can, for all their smallness, leave a certain trace in the world … This faint light, which has left its trace stealthily and quietly in the room, seems at that hour of the night, like a lesson in learning to write again.” Adania Shibli, “On learning to write again,” European Review of Books (June 13, 2022), https://europeanreviewofbooks.com/on-learning-to-write-again/.