I’m no more your mother

Than the cloud that distills a mirror to reflect its own slow

Effacement at the wind’s hand.—Sylvia Plath, “Morning Song” (excerpt)

Why are our lives still governed by binaries? How are binaries such as gender and race maintained, and by whom? I have long been interested in the entrenchment of binary thinking and the systems it reinforces, especially when it comes to conceptions and misconceptions of gender and race in cultural production. Eurocentric white feminism and the way it has evolved over the last thirty years has not helped create a wider, stronger, more powerful alliance between feminisms and LGBTQI+ movements. The intersections between feminisms, and their further intersections with racism, class struggle, social injustice, and disparity, have not been accentuated enough in the mainstream these last decades. The rise of trans-exclusionary radical feminists (TERFs) exemplifies the problem.

The current ascendance of openly racist and radical-right female politicians in the EU and beyond marks a new era in the figure of women in power, perpetuating what I have in the past called “narcissistic authoritarian statism.”1 Political actors who identify as female, taking the baton from Trump and Bolsonaro, have now taken center stage in portraying and implementing what appears to be essentially toxic masculinity: Italy’s Giorgia Meloni and Germany’s Alice Weidel are two prime examples. Considering these women in the context of entrenched binaries can open up new ways of thinking about the politics of care and its relationship to gender—or maybe better put, the connection of care to ideas of what femininity is or should be.

I align myself with those who push for an egalitarian approach to care labor that not only stems from the collective aspect of care but breaks with its feminization—and most certainly breaks with the TERF insistence on biology. The TERF exclusion of people who identify as female but who might or might not have a womb destroys urgently necessary feminist alliances in times of neofascism. TERF ideology makes possession of a womb (as a physical space and bodily trait) nonnegotiable for feminist struggles, and plays an important role in stabilizing and propagating neofascism, entrapping forms of feminism in their cul-de-sacs. To discuss this I will use the figure of the Mother as a representative and/or carrier of a predominantly white-supremacist feminism, which, as Judith Butler recently argued, can go so far as to feed the “anti-gender ideology movement” and fixate on a “phantasm” of essentialized identity, which in turn becomes a conceptual container for neofascism.2 To reflect that essentialism I will use an ironic capital M for “Mother.”

I aim to address the figure of the Mother through her predominant performance: mothercare. According to my embodied experience, the Mother is still, after decades of anti-racist feminist struggle, collectively understood, addressed, and portrayed as a white Western lady whose role is often strongly connected to nature and nurture. What would happen to our feminisms if we refused to continually recreate and enforce this stereotype of what it means to a mother? What if we killed the sanctity of the biological womb? Is doing so a necessary sacrifice in a time of absolute crisis? Why are some left-wing feminists as disgusted with this idea as liberal and far-right feminists? Some claim it is sacrilege and dangerous to abolish the sanctity of the biological womb and the embodied knowledge of having been born a female, given the never-ending femicides, gender pay gaps, and glass ceilings of gender inequality. Many claim that the sacrifices of previous feminists movements have been too great to now abandon them for other categorizations, given the specifics of gestation, breastfeeding, and other bodily facets of reproductive labor. But are these reasons valid enough to continue to exclude and deny womXn without wombs? Does a womb make one a feminist? Does motherhood make one a feminist? Does motherhood make one a good person? Hardly. How does mothercare frame care politics? I would like to propose a new term, drawing from practices that have informed and infused not only radical feminisms, but more broadly the ethics and politics of care: othercare. I propose a practice of care as alterity, a practice that stands opposite to this figure of the Mother.

Mother-Monster Land / Womb Abyss

During my second trimester in summer 2022, the district attorney in Patras, Greece charged a woman for the murder of her children. Roula Pispirigou killed her three daughters—Georgina, Malena, and Irida, respectively aged nine years, three years, and six months old—over a period of three years. She had purposefully made her children ill and taken them to the hospital, suffocated them while sleeping, or poisoned them—apparently to try to keep her husband from cheating on her or leaving her. All three children died under dubious circumstances. The arrest dominated social and mass media in Greece, pushed into the public eye by the outlets close to the neoliberal Mitsotakis government in order to distract from the massive fires across the country in July 2022, which burned thousands of acres of virgin forest and the suburbs of Athens. These were not wildfires but human-made disasters, due to a decade of austerity and a climate-change-denying government that decided not to invest in firefighting staff or equipment. This resulted in an irreparable ecological catastrophe; thousands of animals were burned alive and biodiverse areas were decimated. At the time, I thought about how typical it was for patriarchy to use a woman to cover its crimes against nature and people.

CBS News covers the sentencing of Roula Pispirigou in a March 18, 2025 article titled “Nurse Given 3 Life Sentences for Killing Her 3 Daughters in Greece in Case That Gripped Public for Years.”

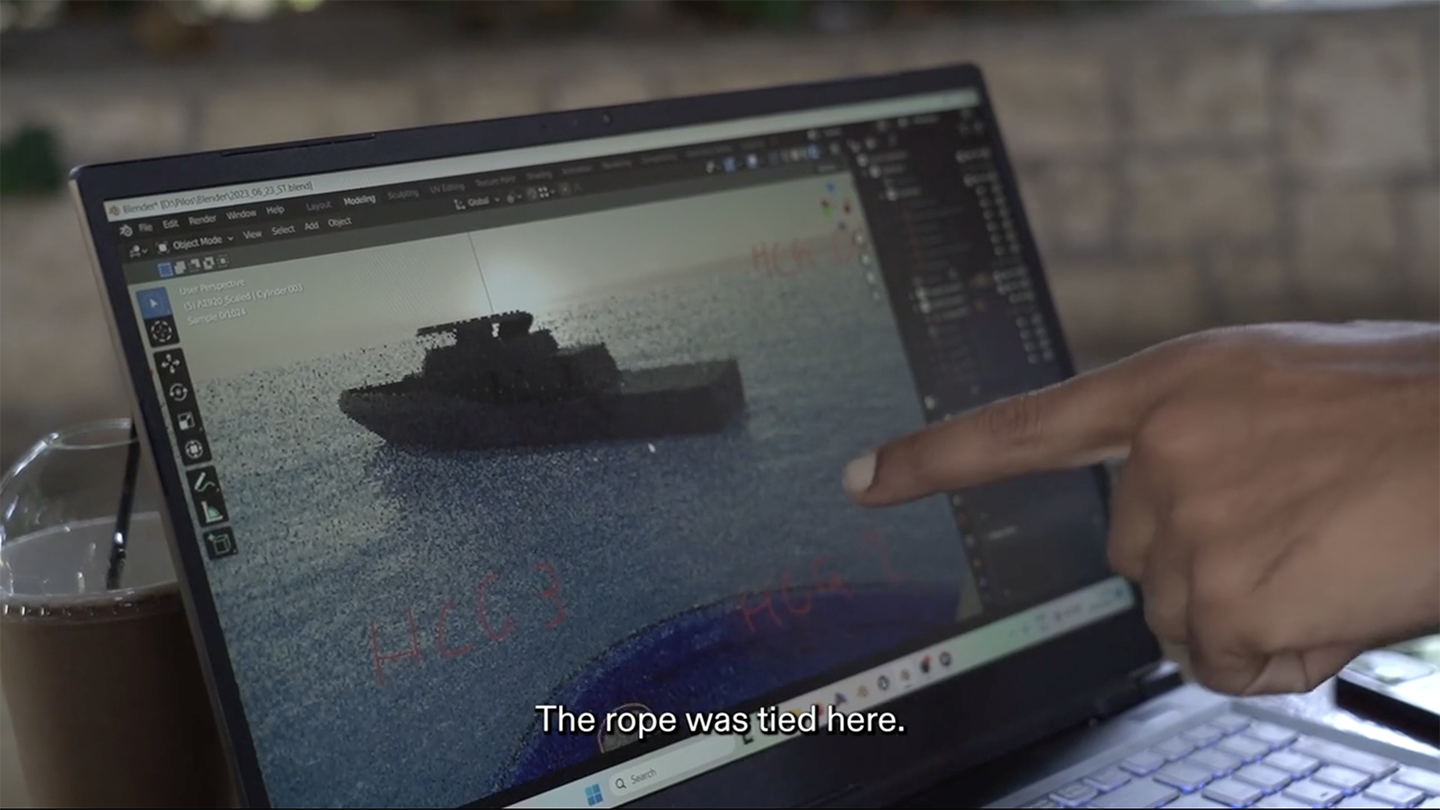

A year later, while I was breastfeeding my newborn, the Adriana, a boat leaving Libya for Italy with hundreds of refugees on board, sank inside the Greek Search and Rescue zone in the Mediterranean Sea. The Pylos shipwreck of June 2023 became the deadliest refugee shipwreck in recent history. Around five hundred people were lost forever, unidentified, deprived not only of their basic human right to asylum (established in 1950), but of a timeless care act common to human and nonhuman animals alike: burial. Refugee drownings in the Mediterranean have been a recurring phenomenon over the past decade, a contemporary equivalent of what Édouard Glissant called the “womb abyss” of the slave ship during the Middle Passage. My thinking begins with this womb abyss:

What is terrifying partakes of the abyss, three times linked to the unknown. First, the time you fell into the belly of the boat. For, in your poetic vision, a boat has no belly; a boat does not swallow up, does not devour; a boat is steered by open skies. Yet, the belly of this boat dissolves you, precipitates you into a nonworld from which you cry out. This boat is a womb, a womb abyss. It generates the clamor of your protests; it also produces all the coming unanimity. Although you are alone in this suffering, you share in the unknown with others whom you have yet to know. This boat is your womb, a matrix, and yet it expels you. This boat: pregnant with as many dead as living under sentence of death. The next abyss was the depths of the sea … In actual fact the abyss is a tautology: the entire ocean, the entire sea gently collapsing in the end into the pleasures of sand, make one vast beginning … Paralleling this mass of water, the third metamorphosis of the abyss thus projects a reverse image of all that had been left behind, not to be regained for generations except—more and more threadbare—in the blue savannas of memory or imagination … Experience of the abyss lies inside and outside the abyss. The torment of those who never escaped it: straight from the belly of the slave ship into the violet belly of the ocean depths they went.3

The Adriana was carrying roughly 750 people, mainly from Syria, Pakistan, and Egypt. Only 104 survived, including only one woman; eighty-two bodies were recovered but only fifty-eight identified. According to survivor testimonies, the more than two hundred women and children aboard were in the hold of the ship, with closed doors for their own safety and privacy. The waters where the Pylos wreckage occurred are the deepest in the Mediterranean, known as the Calypso Deep, at 5109 meters (16,762 feet). According to Greek authorities, the location made it impossible to recover the dead.4

Calypso Deep takes its name from the beguiling sea nymph of Greek mythology, because of course Western science continues to fetishize ancient Greece and its archetypes. In this case, the female name is particularly telling. It translates as “she who conceals knowledge,” from the Greek “καλύπτω,” for “cover,” “hide,” “conceal.” Calypso, siren of sirens, lured Odysseus to the island of Oggia by singing. There she held him captive for seven years, trying to force him to become her immortal husband. Odysseus was referred in ancient Greek as the “πολυμήχανος” (polŭmḗkhănos), or “the ingenious,” “the cunning,” “the crafty”: the one who held knowledge. The myth itself oozes misogyny: Calypso is the archetype of a woman who bewitches a man into a relationship through sexual manipulation. Some feminist readings of the myth of Calypso in The Odyssey suggest that Odysseus was in fact Calypso’s slave during these seven years. In a 2018 article, classics professor Stephanie McCarter asked whether Calypso was a feminist or a rapist. The semi-goddess, in McCarter’s reading, is a classic representative of the Mother I am discussing here: “What Calypso wants is not something new or different from masculine authority but her own feminine one to match it.”5

The Calypso Deep was discovered on September 27, 1965 by three white European men: Captain Gérard Huet de Froberville, Dr. Charles “Chuck” L. Drake, and Henri Germain Delauze, who entered the waters in the French bathyscaphe Archimède. Calypso yet again hides authority and knowledge, just like when she hid Odysseus. Now, in her dark-blue depths she hides the truth about countless victims: hundreds of babies, children, women, and men, concealing their numbers as well as their identities. She is used as a convenient alibi to allow those in power to ignore the magnitude of this tragedy.

During the revelations about the scale of the disaster, the Mitsotakis government, unable to cover up information released by NGOs showing that the Hellenic Coast Guard had received orders from high up to capsize the boat, used an old piece of news to divert attention from this human-made tragedy. A new media frenzy was whipped up by the same government-friendly outlets as before: the case of the modern Medea, the murderous mother Pispirigou, was revived, with fresh details of the babies’ killings. The Mother-monster that is the state, or the supra-state of the European Union, the ultimate white-supremacist Mother, has been drowning people since colonial times and keeps hiding its crimes by using female forms like Calypso and Medea—using them and their associations with nature as distractions or bait.

Although authorities claimed that it was impossible to reach the sunken boat holding the drowned refugees, it is in fact very possible to reach the bottom of the Calypso Deep. The French expedition in 1965 was able to explore and measure its depths. Two years before the Pylos wreckage, in February 2020, Caladan Oceanic, a company owned by billionaire entrepreneur Victor Vescovo, reached the bottom of the Deep with its own submersible. Vescovo himself was on board, together with Prince Albert of Monaco. The 2020 expedition validated that the 1965 mission had reached the deepest point of the Mediterranean Sea.

This kind of technology is only produced for and accessible to the techno-feudalists of the world. It is never available to working class or migrant bodies of color, unless it is used to kill them. The rich white people of the Capitalocene understand the possibilities of exploiting the earth and beyond, conquering the dark matter of the universe, the sea, and our planet’s minerals, but they are uninterested in the “dark” affairs taking place beneath earthly waters. The complete and total indifference of Mother Europe towards her non-white, non-Christian, other children is reflected in the Mediterranean waters and the shiny holiday packages she books for her enjoyment there. It is not enough to say that the EU’s refugee policy is defined by carelessness; more than that, it embodies the necropolitics of dehumanization and death that Achille Mbembe and Silvia Wynter spoke of.6 It is tragically fitting that less-than-white countries are asked to take care of the migrant problem, from Erdogan’s Turkey to Mitsotakis’s Greece. The murderous policies of these governments have been defined in recent years by pushbacks and drift-backs, sponsored by eight hundred million euros from the EU.7 Ursula von der Leyen, the Mother-head of the EU, ensured these funds, and then enjoyed a free holiday at one of Mitsotakis’s villas.8

Mother Racism

The anti-migratory racist hatred towards these other children, and the suffocating self-righteousness of the Mother and what she deems to be “grievable life” (in the words of Judith Butler), have been clear for many decades.9 But it was 9/11 that marked the epoch-defining collapse of the Mother as a benevolent white lady who takes care of all the wretched of this earth, leading to the rise of anti-Muslim sentiment, gung-ho military policies, and unlawful invasions by the West.10 The carnage of the US-made Second Gulf War was so massive that dehumanization had to go on overdrive: the crimes of the Iraq invasion remain hidden and unpunished, but ironically are used today to justify the current killing frenzy by those who commit genocidal acts.11 The numbers are staggering: one study estimated the civilian death toll of the Second Gulf War at 461,000.12

Those innocent Iraqi civilians were meant to remain faceless, nameless numbers: the death of the “soul of [one’s] soul” was even then a death with no process, no honors, no rituals.13 One might have thought that the elected officials responsible for these crimes would be punished and shamed for lying to voters about Saddam Hussein’s alleged weapons of mass destruction. Unfortunately, killing with impunity has only gotten worse since then. The Mother’s continued moral bankruptcy is epitomized by the tragedy of Gaza over the last two years. The dehumanization of brown life after 9/11, together with the normalization of racist politics in the mainstream Western public sphere, paved the way for the horror unfolding in Palestine.

The death of Israeli civilians on October 7 was rightfully deemed worthy of mourning by the Mother, but her care labor stopped there. Since then, the deaths of civilians in Gaza have often been deemed “collateral damage”—less important and unworthy of mourning. In Germany—the Mother of all European nations for decades now—the duty of mourning a life, and most importantly of saving a life, has been sidelined by the country’s obsessive, illogical Staatsräson.14 It’s hard to believe that Germany has real remorse for its colonial and Nazi past given that a large segment of the population normalizes the neofascist political party Alternative für Deutschland, with its racist and Nazi references (in slogans like “Alles für Deutschland”) and its collusion with far-right paramilitary groups seeking to deport migrants. As a descendant of victims of Nazi atrocities, I am sad to say that Germany has clearly failed to learn from its mistakes.15 It uses the war in Gaza to absolve itself of the horror of all horrors, the Holocaust. This hypocrisy was recently epitomized, in the cultural realm, by German cultural minister Claudia Roth. At the 2024 Berlinale, Roth insisted that when she clapped for the best documentary winner, No Other Land (which would go on to win a best-documentary Oscar as well), she was only applauding for the two Israeli members of the four-person directing team. The other two are Palestinian.

The Mother is not only a person or nation or continent; it is also the West’s self-flattering idea of itself. The West portrays itself as the Mother of all Mothers, the beacon of truth and civilization, the arbiter of law and justice. This idea has always been hypocritical, but after the war in Gaza, the West’s claim to defend “civilization” has been exposed as grotesque. Indeed, we may have reached a full-circle moment in history: Mother is finally accepting her true nature, as she revisits with pride her past of colonial plunder. This historical period gave rise to the global order we know today, as argued by Raoul Peck’s brilliant docuseries Exterminate All the Brutes (2021). It’s when Mother gave birth to Western capitalism, when she initiated the erasure of nature by declaring her total detachment from it, and when she murdered countless “brutes” through bloodthirsty conquest. Like Medea, Mother today is happy to kill her children—both ideological (progress, justice, equality) and actual—for the sake of power, as she saunters up to a podium and gives a Nazi salute.16

White Mother-Boards

The Mother needs to die. And we can kill her if we destroy the Motherboard: the central system that gives commands. It is already broken in so many ways. Given this, a new concept of the mother needs to emerge, one that discusses mothercare without the M, one that propagates care as alterity. In mothercare transformed into othercare, multiple mothers can take care of you. It might be a cyborg or a mechanical womb that breeds and feeds you. You are the responsibility of many; you are a collective endeavor. Othercare builds on the societal structures of Indigenous and First Nations communities that have long understood kinship practices as collectivist performances of care, and that include humans and nonhumans alike. Those in need of care are collectively cared for from a pool of others that (lower-case) mother, regardless of their biology. The system of beliefs underpinning these practices is not beholden to binaries and goes beyond the human. In the words of María Puig de la Bellacasa, this system sees

care as a human trouble but this does not make of care a human-only matter. Affirming the absurdity of disentangling human and nonhuman relations of care and the ethicalities involved requires decentering human agencies, as well as remaining close to the predicaments and inheritances of situated human doings.17

Selma Selman, Motherboards, 2023. Copyright Selma Selman, supported by KRASS – Kultur Crash Festival, 2023, Hamburg. Photograph by Mario Ilić.

In her performance Motherboards (2023–ongoing), artist Selma Selman pries gold from discarded electronics. With the help of her family, she disassembles electronic waste and recycles the extracted gold (a material that symbolizes so many things: affluence, desire, early banking systems, the settler goldrush in the US, and so much more). Selman is a Bosnian artist of Romani descent, and her repurposing of material through gleaning refers to the resilience of her family. It also points to the collective and undervalued labor of all those who collect scrap metal and repurpose it. The gold she recovers is transformed into a carefully constructed sculpture: a golden nail. And the noise resulting from the process is turned into a musical composition. To me, Selman’s work highlights communities that have not only managed to survive the Mother nation and its systems of statecraft and bureaucracy, but to thrive against all odds, through collective care structures. In her own words:

The essence is that the Roma population started recycling iron and other types of waste a hundred years ago, for survival, and on the other hand, to save the planet. To me, this is much more important than today’s West, which has only now understood the economic and ecological essence of recycling. So, my work questions that position of the Western white world towards the minority Roma population. And then it can also be read as a feminist work, questioning capitalism.18

M-otherhood

Mother is not only the state, the nation, or the idea of the West. It is also the way that the illusion of Mothering suffocates even the most feminist of mothers. This is explored in Candice Breitz’s film Mother (2005) (one half of her diptych Mother and Father), where six white Hollywood actresses passionately perform the rites of motherhood. They embody blockbuster character types: the self-denying mother who exists in a state of perpetual hysteria (“Everything I did, I did out of love for you!”); the mother who did not want to become a mother; and so on. The work was shown recently in the group exhibition “Good Mom/Bad Mom” at the Centraal Museum Utrecht, one of many recent exhibitions that aim to discuss motherhood—but that mostly fail to disengage it from biology. It is telling that Breitz’s film depicts six white American actresses of different generations, all ambassadors of the dominant narratives of the Western cinematic canon.

Candice Breitz, Mother, 2005, six-channel installation. Courtesy of the artist.

Predominantly Western or West-oriented feminist theory has had an ambivalent, if not tense, relationship to motherhood. Radical feminists of the second half of the twentieth century were at best suspicious of the human gestation and care labor involved in motherhood. Some argued that these practices could only be exploited by patriarchy to perpetuate the subjugation of women. Shulamith Firestone famously wrote in The Dialectic of Sex that “the heart of woman’s oppression is her child-bearing and child-rearing role.”19 To liberate women, she argued, we first need to redistribute the burden of reproducing the species. Firestone described pregnancy as barbaric and proposed ectogenesis as a solution—the production of human fetuses outside of female bodies, in artificial wombs. Firestone’s proposal is extremely relevant today, not only because fifty years later we may be close to making it scientifically possible, but also because she highlighted the way technology is controlled by patriarchy and needs to be reclaimed by feminists.

A decade after Firestone’s book came out, this debate on motherhood was furthered by lesbian feminist poet and theorist Adrienne Rich in her much-discussed book Of Woman Born (1986). Rich made a crucial distinction between the experience of motherhood (“the potential relationship of any woman to her powers of reproduction and to children”) and the institution of motherhood (“which aims at ensuring the potential—and all women—shall remain under male control.”)20 Around the same time, some feminist theorists began to highlight motherhood’s intersection with class and race. bell hooks famously discussed this in her 1984 book Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center:

White women who dominate feminist discourse today rarely question whether or not their perspective on women’s reality is true to the lived experiences of women as a collective group … Feminist theory lacks wholeness, lacks the broad analysis that could encompass a variety of human experiences.21

The most compelling argument in hooks’s book concerns white second-wave feminists and their position on care and reproductive labor: their solution to oppression is to exit the home for the workplace. hooks contends that this has never been a preoccupation of Black women: “Had Black women voiced their views on motherhood, it would not have been named a serious obstacle to our freedom as women. Racism, availability of jobs, lack of skills or education … would have been at the top of the list—but not motherhood.”22 She highlights the way racial capitalism produces different feminist experiences. hooks’s thinking ties in with Angela Davis’s influential book Women, Race and Class (1981). Here Davis challenges the Wages for Housework demand to be paid for care labor (as advocated by seventies feminists such as Silvia Federici), juxtaposing this with the reality of Black women who, “as paid housekeepers, have been called upon to be surrogate wives and mothers in millions of white homes.”23 Davis points out that in the US,

the majority of Black women have worked outside their homes. During slavery, women toiled alongside their men in the cotton and tobacco fields, and when industry moved into the South, they could be seen in tobacco factories, sugar refineries and even in lumber mills and on crews pounding steel for the railroads. In labor, slave women were the equals of their men. Because they suffered a grueling sexual equality at work, they enjoyed a greater sexual equality at home in the slave quarters than did their white sisters who were “housewives.” As a direct consequence of their outside work—as “free” women no less than as slaves—housework has never been the central focus of Black women’s lives. They have largely escaped the psychological damage industrial capitalism inflicted on white middle-class housewives, whose alleged virtues were feminine weakness and wifely submissiveness. Black women could hardly strive for weakness; they had to become strong, for their families and their communities needed their strength to survive … Black women, however, have paid a heavy price for the strengths they have acquired and the relative independence they have enjoyed. While they have seldom been “just housewives” they have always done their housework. They have thus carried the double burden of wage labor and housework.24

Davis, hooks, and Rich address situated feminist experiences and the different kinds of feminism they have produced. More recently, Sophie Lewis has examined the relationship between gestation labor and capitalism in her book Full Surrogacy Now (2019). She asks: “What if we reimagined pregnancy, and not just its prescribed aftermath, as work under capitalism—that is, as something to be struggled in and against toward a utopian horizon free of work and free of value?”25 Jenny Brown, in turn, proposes the option of a “birth strike” in her 2019 book of the same name, where she lays out a compelling analysis of the role of late capitalism in reproductive labor. She argues that feminists should seek to control the means of reproduction and demand a reassessment of the state’s support for care labor. Lewis’s more recent book Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation (2022), which draws from early radical feminists like Alexandra Kollontai, proposes that care labor could be something that happens outside of the family structure, and offers the term “comrades” instead of “kin.”

Care as Alterity: A Beginning

In a world where we are witnessing the rebirth of fascism—or more accurately the successful gestation of neofascism—it is crucial to recognize the important role played by the quintessential Mother: she is deployed to maintain stability, order, and authority by way of biology. From Meloni’s changes to laws concerning reproductive and parental rights, to Musk’s obsession with eugenics, to the return of the traditional family form via the destruction of reproductive rights, the Mother as a figure of biologically defined, binary heteronormativity is reemerging everywhere. Women who support these ideas are even cashing in on the figure of the Mother. Legions of social media “tradwives” promote traditional motherhood, mixing it with fashion endorsements and product placement. Until recently, some led their millions of followers to believe they voted progressive. Now they wear their MAGA hats shamelessly.

Thankfully, there are “other-mothers” shaking the foundations of these fortresses of binarism. One excellent example is the mothers of ballroom culture, who for decades have been taking in, raising, and proudly parenting queer kids rejected by their biological parents, from the US to the Philippines. They are a model of othercare that I will discuss further in the second part of this essay. Another example of othercare is the group Mothers Against Genocide, which has been practicing alternative motherhood by seeking to soften the censorship of Meta’s platforms and advocating for accountability for war crimes in Palestine. In the cultural realm, a group of cultural workers named Matri-Archi(tecture), founded by Khensani Jurczok-de Klerk, recently organized a series of gatherings modelled on the South African tradition of the stokvel. This is an informal “savings pool,” typically organized by Black women, to which members contribute funds on a rotating basis, allowing contributors to later withdraw lump sums to pay for things they need. Members usually gather monthly in the home of another member. The stokvel provides a familiar social space for fellowship and community. Matri-Archi(tecture) organizes gatherings that aim to catalyze a collective reimagination of the conditions under which we collaborate, using care as an ethic and point of departure.26

Othercare is not just a possibility or proposal but a necessity for fighting back against the new wave of far-right racist patriarchy. Abandoning our reproductive organs for collective liberation is the only way for feminisms to come back to life. A womb does not make one a feminist—or a good person for that matter. Nor does giving birth make one a good carer and parent, because care is not tied to biology and familial bonds. One way to set ourselves apart from the Mother is to conceive of care as alterity. The Mother is deeply rooted in the belief that binaries are not to be challenged, changed, or abolished. Through othercare, we can find new terms to describe selfless love. In the words of Sophie K. Rosa, “foregrounding connection, care and community in our political analyses and action can be powerful.”27 Seizing our means of reproduction and redefining who cares for whom and why might be the only path to the broad alliances that offer a way out of the dark misanthropy that lies ahead.

Judith Butler, Who’s Afraid of Gender? (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2024), 13, 6.

Édouard Glissant, The Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (University of Michigan Press, 1997), 6.

“Greece: One Year on From the Pylos Shipwreck, the Coast Guard’s Role Must Be Investigated,” News, amnesty.org, June 13, 2024 →.

Stephanie McCarter, “Is Homer’s Calypso a Feminist Icon or a Rapist?” Electric Literature, January 30, 2018 →.

Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics (Duke University Press, 2019); Sylvia Wynter, Black Metamorphosis: New Natives in a New World, unpublished manuscript →.

Nektaria Stamouli, “Von der Leyen’s Holiday to Greece Prompts Criticism from Top EU Watchdog,” Politico Europe, November 26, 2024 →.

Butler, Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 6.

Butler, Who’s Afraid of Gender?, 6.

John Yoon and Zach Montague, “Biden Says He Urged Netanyahu to Accommodate Palestinians’ ‘Legitimate Concerns,’” New York Times, January 17, 2025 →.

“Iraq Study Estimates War-Related Deaths at 461,000,” BBC News, October 16, 2013 →.

In a November 2023 video that went viral, Khaled Nabhan, a Palestinian grandfather, mourned the death of his four-year-old granddaughter Reem, calling her “the soul of my soul.” She and her five-year-old brother were killed by an Israeli airstrike in Gaza. In December 2024, Khaled was himself killed by an Israeli tank shell. See Abeer Salman and Nadeen Ebrahim, “Palestinian Grandfather Whose Tribute to Slain Granddaughter Went Viral Is Killed by Israeli Fire in Gaza,” CNN, December 16, 2024 →.

Lena Obermaier, “‘We Are All Israelis’: The Consequences of Germany’s Staatsräson,” Sada, March 28, 2024 →.

Very few people I’ve met in my life know of the Nazi atrocities committed outside of Western Europe, maybe because these peripheries inhabited by lesser white people fall into the category of ungrievable life. Frankly, very few Germans I’ve met even know that the Nazis invaded Greece. More information about the invasion can be found in the book The Black Book of Nazi Atrocities in Greece, a product of the colossal research of survivors, available to download for free in Greek and German →. The deaths of my family members are noted within the book’s thirty-five pages of documented killings and mass murders (p. 62–97), many of which took place in what Greeks since 1940 have called “holocaust” villages (the word having entered Greek in the 1920s due to the Greek and Armenian genocide of 1915–23).

This is a reference to the apparent Nazi salute given by Elon Musk at a rally following Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration in January. See Lauren Aratani, “Elon Musk’s Daughter Says Father’s Rally Gesture Was ‘Definitely a Nazi Salute,” The Guardian, March 20, 2025 →.

María Puig de la Bellacasa, Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds (University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 18.

Selma Selman, “Alchemy at Work,” interview by Miloš Trakilović, Vogue, March 15, 2024 →.

Shulamith Firestone, The Dialectic of Sex (William Morrow, 1970), 58.

Adrienne Rich, Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution (Norton, 1986), 13.

bell hooks, Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (Routledge, 1984), 3.

hooks, Feminist Theory, 133.

Angela Davis, Women, Race and Class (Random House, 1981), 230.

Davis, Women, Race and Class, 230.

Sophie Lewis, Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against Family (Verso, 2019), 11.

Sophie K. Rosa, Radical Intimacy (Pluto Press, 2023), 7.

Subject

The author would like to thank artist Cameron Rowland for directing me to “Womb Abyss,” and Elvia Wilk for her intrepid editing. This text is dedicated to K and other trans activist friends in Berlin and beyond who have been showing me what true love for your fellow human means.