For Dri

Bogdanov in the Anthropocene

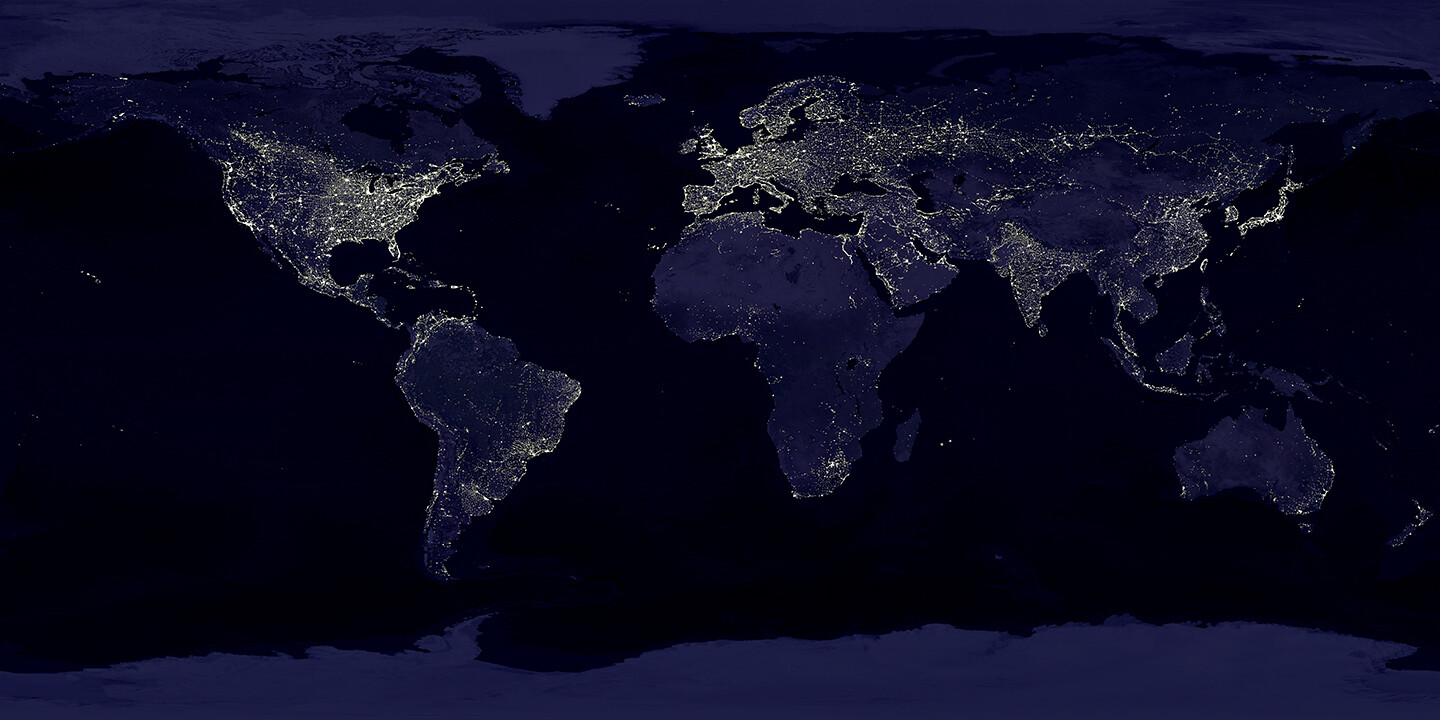

There is much in Aleksander Bogdanov to make him appear as a contemporary for those of us living in the so-called Anthropocene: the view of the universe, and by extension the planet, as a self-organized process in which everything is connected; the emphasis on the entropic force of disorganization and the constant tension between the activities-resistances of humans and their milieu; the certainty of the impossibility of a final equilibrium in any relationship with the environment; the understanding that the imperative of viability and adaptation also applies to humankind, which puts it in a potentially precarious situation in a world that is changing rapidly. All this seems to make Bogdanov a contemporary for those of us who inhabit the Anthropocene. More than that: at a time when many claim that the ecological crisis forces us to think beyond anthropocentric exceptionalism, the Russian thinker’s monism (which drives him in his search for a single set of principles from which to think the physical and the mental, the human and the nonhuman, the natural and the artificial, the living and the nonliving) and the organizational point of view that follows from it (with the perspectivism and the great levelling that the concept of activity-resistance connotes) indicate that, for Bogdanov, the idea of extending agency beyond the limits of the human would not represent anything new. Finally, as McKenzie Wark has pointed out, Bogdanov demonstrated a visionary awareness for his time of life as “part of a self-regulating system, although not necessarily one that will always find equilibrium,” and of humankind’s collective labor as something that “transforms nature at the level of the [planetary] totality.”1

What, however, are we to make today of Bogdanov’s assertion that the aim of humankind is “dominion over nature,”2 or his vision of the “human collective” as the “organising centre for the rest of nature,” which “‘subordinates’ and ‘rules over’ it … to the extent of its energies and experience?”3 One must heed, first of all, Bogdanov’s observation that expressions such as “conquest,” “subordination,” and “ruling over” are metaphors through which authoritarian forms of social organization inadequately named the tektological phenomenon of “egression,” whereby a complex within a wider system comes to exert a preponderant influence over the other elements of that system.4 Seen without the fetishes of previous historical moments, the notion of humankind as the “universal egression”—universal in the sense of tending towards expansion, although always effectively limited in its scope—would exclude neither the agency of the nonhuman, nor the possibility of another type of relationship than simple domination between the human and its environment. Rather, it would simply name the fact that humans have revealed themselves, in the share of space-time that they have occupied within “the great universal organiser, nature,” to be the complex with the greatest organizing power over what surrounded it.5 Instead of a teleological destiny or metaphysical eminence, in other words, we have here no more than a statement of fact.

Trinity Site explosion, 0.016 second after explosion, July 16, 1945. The viewed hemisphere’s highest point in this image is about 200 meters high. Image: Berlyn Brixner / Los Alamos National Laboratory. License: Public Domain.

This fact, nevertheless, has turned out to have a tragic underside: the concept of the Anthropocene marks the definitive realization that this organizing power is, at the same time, a disorganizing power on a planetary, geological scale. If not anticipated by Bogdanov as such, however, this awareness does not indicate an entirely blind spot in his thinking. To see how it is possible to think the Anthropocene from the perspective of the “universal science of organization,” it is enough to recall the perspectivity of Bogdanov’s concept of activity-resistance, the principle according to which organization always involves an expenditure of energy, and the observation that the metaphor of the “struggle” against nature expresses a “disorganising correlation.”6

Here, Bogdanov is clearly considering the relationship from only one of the points of view involved: nature “disorganizes” humanity, that is, it resists the latter’s efforts to transform it according to its ends. As we saw above, however, a gain in organization in one part always implies a loss of organization in another, for two reasons: because elements and connections that previously belonged to one complex end up being consumed, transformed, or integrated into another; and because in the activities necessary for this consumption, transformation, or integration, part of the energy expended is permanently lost in the form of heat. Wiener’s “local and temporary islands of decreasing entropy” feed off the organization that exists elsewhere, and as such actively contribute to the growth of entropy not only in these parts, but in general.7

Organization is, in short, a local phenomenon that always implies the transfer of disorganization and entropy to some other place. (You only have to look at the private life of a community or union organizer to see this.) Based on this principle, tektology is in a perfect position to give us an explanation of how and why the organizing activity of “universal egression” could prove to be a disorganizing force on both a local and global scale. It suffices to think that, as this activity grows in power and scope, nature begins to respond not only with the passive (local) resistance of its arrangements and the (general) entropy that increases as a consequence of the activity needed to undo them, but also with the activity of a series of new (global) arrangements and nonlinear reactions triggered by the advance of human action.

In other words, humankind’s organizing action, in the same process in which it demonstrates itself to be disorganizing of nature, also manifests itself as reorganizing it, and it is the activity resulting from this reorganization that eventually presents itself to humanity as resistance, that is, as a disorganizing force. If it is the export of entropy that “enables some to assert the existence of progress,” the ecological crisis signals the realization that there is a limit to the possibility of continuing to export entropy within a closed system without threatening its equilibrium to such an extent that the very continuity of the progress thus built is threatened.8

It should be noted, however, that this explanation is, at the same time, an interdiction to any moral reading of the Anthropocene and the expansion of agency beyond the human. To exist is to organize oneself, and to organize inevitably entails costs; this applies to us as much as to any other being, and to say “good” or “bad,” gains or costs, always implies also asking “for whom?” What has made humans a disorganizing force on a global scale is not some moral flaw characteristic of the species, which would make it constitutively immune to a predisposition to harmony spontaneous in all others, but rather the combination of a system of production and distribution of wealth that demands constant expansion, and an enormous mismatch between the growth in the capacity to produce effects and the capacity to calculate their costs. Recognizing the nonhuman can give us another perspective from which to make this calculation, but it cannot eliminate the fact that action has costs. It is undoubtedly necessary to drastically reduce those and rethink from top to bottom the priorities according to which they are taken on, as well as the criteria for their distribution, and that of gains. But the fantasy of a power to that is not immediately also a power over, or of an organization that does not involve costs, does nothing to help the real challenge, which is to find a dynamic equilibrium with the environment in which the maximum flourishing of life, human and nonhuman, is possible.

Granted, from the thought that everything comes at a cost can follow practically any course of action, and the tone of hard-nosed, “no such thing as a free lunch” realism it evinces is more often than not at the service of justifying the worst—not least the sort of behavior that has brought us to the verge of ecological collapse. “The norms of expediency,” as Bogdanov points out, “will point with equal conviction to helping one’s neighbour and to cutting his throat.”9 What tektology can make us see, however, is that one need not deny that costs are real in order to oppose such positions; and, conversely, that to believe in the reality of costs does not entail agreeing with how mainstream economic and political discourses calculate what gains are desirable, what (and whose) losses are acceptable, and what trade-offs are worth it. The real question lies in the criteria and how they are decided; by abandoning to these discourses the terrain of realism, what one ultimately relinquishes is, in fact, the prospect of questioning the air of self-evidence in which the criteria they assume tend to come wrapped.

Bogdanov is perhaps a tad too naive (or disingenuous) in claiming that, once society is based on comradely cooperation, “goals and diverse norms that serve them [will] coalesce in a socially coordinated struggle for happiness.”10 After all, clarity regarding “the universal ultimate goal” —“to achieve the maximum life for society as a whole that, at the same time, would correlate with the maximum life for the individuals who comprise it”—cannot guarantee that the means to achieve it, and the standards with which to judge them, would automatically become transparent.11 For reasons we have already seen, such evaluations cannot transcend their perspectival condition, and therefore may not only not be equally good for “all” (however broadly or narrowly we may wish to interpret that word) but might also be wrong (in the sense of setting unanticipated counter-finalities in motion). Yet Bogdanov’s ideal can remain a valuable guide if we bring to the fore the interdependence that is already implied in the tektological project. This allows us to view the “struggle for everything that life and nature can give to humankind” as including, rather than striving to emancipate itself from, both nonhuman nature and nonhuman life.12 The goal then becomes—in a very broad sense that can only be broken down into concrete evaluations in partial and uncertain terms—one of sustaining a dynamic equilibrium with the environment in which the maximum flourishing of life, human and otherwise, is possible. Or, as Wark puts it, the great organizational “quest” remains the one “to find and found a totality within which to cultivate the surplus of life.”13

Whose quest though? One point where Bogdanov remains faithful to a certain humanism that precedes and runs through Marxism is the ease with which he refers to humankind as a collective subject. It is true that this subject is split almost from the start by the division between organizers and executors, which is expressed from modernity onwards in the opposition between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. But at no point does he seem to doubt the unilinearity of a history in which, even if momentarily separated from this scheme, all human collectives finally tend to incorporate themselves into it and, after eliminating that original split, come together in a single community of organizers of their world. Nevertheless, in Bogdanov’s writings it is possible to find useful principles for thinking about the synchronous coexistence of diverse human collectives, another issue that the Anthropocene brings to the fore in full force.14

His insistence that “cognition is an adaptation” whose “‘truth’ boils down to its fitness to govern practice,” and that “the collective is always the subject of practice,”15 and therefore also of cognition, amounts to ascribing truth to all knowledge that has become settled in the practice of any group whatsoever in its encounter with everything that resists its labor—that is, “nature.”16 Arising from the friction between collective activity, under its specific conditions of organization, and the activities of the things that populate the environment, truth is always simultaneously objective (because it is limited by the regularities that practice reveals) and relative (because it is conditioned by the relations of production and the contingencies that are specific to encounters—for instance, the greater or lesser natural diversity available within a collectivity’s field of action). Since this encounter takes place continuously over time, and its conditions, both social and natural, are changeable, it never reaches a definitive stage, which would be equivalent to a state of static equilibrium: “There can be no absolute and eternal philosophical [or scientific] truth.”17 This other dimension of Bogdanovian perspectivism can be very useful when faced with an issue such as the environmental crisis, which involves and requires reconciling a complex ecology of knowledge and practices, insofar as it establishes a pluralism that does not forsake objectivity altogether.

Shelters in Kenya for those displaced by the 2011 Horn of Africa drought. License: CC BY 2.0.

What is more, it helps us not to lose sight of what is ultimately the point in incorporating a plurality of perspectives. If truth never ceases to be relative, it is nevertheless possible to increase its degree of generality by expanding the number of results and methods accumulated in different fields of experience that it is capable of integrating and organizing.18 The relative becomes less relative—that is, relative to more things—in the process of attempting to elaborate the system of its own relativity. The assumption of historical unilinearity and the confidence in the emergence of a class destined to take on all of humanity’s tasks leads Bogdanov to believe that the project “to unify the experience of all people of past and present generations into a rigorous and coherent system for understanding the world” could converge into a single science.19 Awareness of the very high prices and enormous blind spots of the process of economic, technical, and cultural unification imposed and propitiated by colonial expansion gives us reason to be much more skeptical about the motivations, viability, and desirability of any such unifying pretensions. What reading Bogdanov today reminds us, however, is that such skepticism should be used pharmacologically, as a prudential principle and a tool for controlling the results of systematization efforts, and not as a reason to give up on such efforts once and for all.

The contemporary “polycrisis,” with the ecological emergency at the forefront, presents us with “organisational tasks of unparalleled breadth and complexity,” the resolution of which cannot be “haphazard or spontaneous.” The answer is not less coordination, but more; and this requires not fewer attempts at global modelling, but more and better, more diverse and self-reflective, from different perspectives and at different scales of granularity. For Bogdanov, democracy is a cognitive and practical imperative rather than a matter of ethics or recognition issue: “synthetic” or “comradely” cooperation is capable of greater achievements because a complex collective modeler is, in principle, capable of more complex models. We can be more moderate than him in our optimism without completely abandoning this insight.

The Augustinian Left

A little over a decade ago, the British art historian T. J. Clark caused a stir with a text that called for the creation of a “left without a future”: one that did not expect anything “transfiguring” to happen, but rather adopted for itself a pessimism about human nature that had, in the Enlightenment, been the preserve—and strength—of the right:

There will be no future, I am saying finally, without war, poverty, Malthusian panic, tyranny, cruelty, classes, dead time and all the ills the flesh is heir to, because there will be no future; only a present in which the left … struggles to gather the “material for a society” Nietzsche thought had vanished from the earth.20

Porcelain figurine “I.V. Stalin votes” by A. Sotnikov, Dulevo Porcelain Factory, USSR, 1950.

As we have seen so far, Bogdanov occupies a diagonal position in relation to the list of ineliminable givens that Clark compiles. On the one hand, Bogdanov genuinely believed in the possibility of the end of classes, poverty, and tyranny; on the other, he did not mistake this for the end of risk, of effort, of resistance imposed by the environment, or even, as Red Star demonstrates, of the struggle against the scarcity of resources, the danger of overpopulation and, eventually, war itself (even if interplanetary). The difference lies, firstly, in where the source of such ills is situated: for Clark, it is in a human nature burdened with an innate tendency towards radical evil; for the Russian author, it is in the play of activity-resistance, in the material and energetic cost of each single thing, in the external and internal work of disorganization. This results in a difference of orientation. Clark’s left must function as a katechon, and its radicality resides in its recognition of the constant presence of radical evil and its ability to contain its worst effects. Bogdanov’s, on the other hand, does not give up on its ambitions in the least, but confronts them without the illusion of a final point of equilibrium; its work never ends, not because the worst is always near, but because disorganization is always there, nothing comes without a cost, and entropy and the dangers of relapse gnaw away at every struggle that aims to make way for the maximum possible abundance and freedom for those who take part in it.

Two lefts, then, one Manichean, the other Augustinian. Which of the two is more deserving of the title of “tragic” that Clark claims? The tragedy of the first is merely human, that of subjects we see “perishing, devouring one another and destroying themselves, often with dreadful pain, as though they came into being for no other end.”21 That of the second is cosmic: it concerns complexes or systems subject to the same mechanisms and laws in a universe where disorganization never goes away, entropy grows, there are nonnegotiable limits, action and inaction have irreversible costs and effects. Although it boasts a disillusioned and “grown up”22 tone as one of its distinctive features, the former still has in common with much left-wing political thought the fact that it occupies the perspective of a specific type of protagonist: a hero of grand gestures, the activist who throws his life away at the moment when the crisis spills over into conflict or the statesman who weighs up serious and difficult decisions. The only difference here is that the gesture is katechontic instead of Promethean or transfiguring. Bogdanov places us in the point of view of a rarer character, the organizer. A hero whose gestures are less exceptional, in size as well as in frequency, whose pathos is not that of someone who is always faced with the hour of decision, nor of someone who still fantasizes about a final equilibrium, but rather the resigned irresignation of someone who understands that doing and maintaining something always has its cost, that things require continuous effort, that given enough time and not enough work, everything will unravel, that not only is “the struggle itself towards the heights … enough to fill the heart” but that there is much to celebrate along the way23—someone who knows that the true human tragedy is the awareness of contingency, of counter-finality, of the inevitability of choices and trade-offs, and of their irreversibility, but who also knows that this does not give anyone an excuse for insensitivity in the face of suffering. Someone who fights not because victory is certain, but because not fighting—that is, not caring about existing—would be impossible.

Mckenzie Wark, Molecular Red: Theory for the Anthropocene (Verso, 2015), 54, 12. Wark’s work has played a major role in the recent revival of the Russian thinker in the English language.

Aleksander Bogdanov, Essays in Tektology: The General Science of Organization (Intersystems Publications, 1984), 1.

Bogdanov, Essays in Tektology, 184.

Bogdanov, Essays in Tektology, 184.

Bogdanov, Essays in Tektology, 63.

Bogdanov, Essays in Tektology, 184.

This is equivalent to Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen’s insight into the economic process as the transformation of “low” into “high entropy.” Such a convergence is no surprise; like Bogdanov, Georgescu-Roegen was greatly influenced by the philosopher and physicist Ernst Mach. See Nicholas Georgescu-Rogen, The Entropy Law and the Economic Process (Harvard University Press, 1971).

Closed, that is, in the technical sense of the term: it exchanges energy but not matter with its environment.

Aleksander Bogdanov, “Goals and Norms of Life,” in Russian Cosmism, ed. Boris Groys (e-flux journal and MIT Press, 2018), 194.

Bogdanov, “Goals and Norms of Life,” 185.

Bogdanov, “Goals and Norms of Life,” 185.

Bogdanov, “Goals and Norms of Life,” 185.

Wark, Molecular Red, 11.

Although he personally does have some unfortunate remarks to make about this synchronic diversity. Aleksander Bogdanov, Philosophy of Living Experience: Popular Outlines (Haymarket, 2016), 24–25.

Bogdanov, Philosophy of Living Experience, 158, 249.

“Nature is what people call the endlessly unfolding field of their labour-experience.” Bogdanov, Philosophy of Living Experience, 42. This should be understood as a sort of retrospective projection, of course: the idea is that, regardless of what concept was used by different human collectivities to designate this totality, it is equivalent to “nature” as Bogdanov understands it; and even if a group did not itself have the concept of such a totality, its experience could still be gathered in such a way.

Bogdanov, Philosophy of Living Experience, 13.

For Bogdanov, as for Claude Lévi-Strauss, the impulse in this direction is an internal demand of thought itself, which he explains in organizational terms: “Any organisation is organised precisely to the extent that it is integrated and holistic. This is the necessary condition for viability. This is also true of cognition, once we recognise that cognition represents the organisation of experience. Therefore cognition always tends toward unity, toward monism.” Bogdanov, Philosophy of Living Experience, 236.

Bogdanov, Philosophy of Living Experience 10.

T. J. Clark, “For a Left with No Future,” New Left Review, no. 74 (2012): 75. For a sharp rejoinder, see Alberto Toscano, “Politics in a Tragic Key,” Radical Philosophy, no. 180 (2013).

A. C. Bradley, Shakespearean Tragedy: Essays on Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth (MacMillan & Co., 1912), 23.

Clark, “For a Left with No Future,” 59.

Albert Camus, Le Mythe de Sysyphe (Gallimard, 1942), 168. My translation.

Category

Subject

This two-part text is a version of the introductory essay to the Brazilian edition of Aleksander Bogdanov’s Essays on Tektology (Ensaios de Tectologia: A Ciência Universal da Organização, Machado, 2025).