I first met Boris Groys in Mexico City in 2004, during a conference on contemporary art ambitiously titled “Resistance.” I had never participated in a large-scale international conference or even spoken in public before and it was a truly intimidating experience: I was so nervous that I couldn’t sleep the night before, then drank so much coffee in the morning that my body was literally shaking to the point that my speech became unintelligible. The simultaneous translator basically gave up because she couldn’t make out what I was saying, and I was speaking way too fast anyhow. It was an excruciating experience, and I couldn’t wait for it to end. After I had finally finished and left the stage, the organizers introduced me to Boris Groys. What first struck me about him was his incredible, almost supernatural calm. He seemed like the calmest person I have ever met in my life—not by way of indifference or disinterest, but by way of a certain philosophical tranquility that I had read about but not yet encountered in a person.

I was already familiar with Mexico City, having spent plenty of time there in previous years, so the conference organizers asked me to take Boris sightseeing. We went to the famous Museum of Anthropology and then to the house of Leon Trotsky. In the garden of Trotsky’s house Boris noticed a simple cement tombstone marking Trotsky’s grave, which struck me as a faint reflection of the spectacular and luxurious mausoleum where Lenin lies mummified in Moscow’s Red Square. I remember Boris saying ironically that at least Trotsky got his own mausoleum—his nemesis Stalin was evicted from Lenin’s mausoleum. I also remember how the staff at Trotsky’s house seemed suspicious of us. Perhaps the memory of Stalin’s agents’ past infiltrations and the assassination still linger.

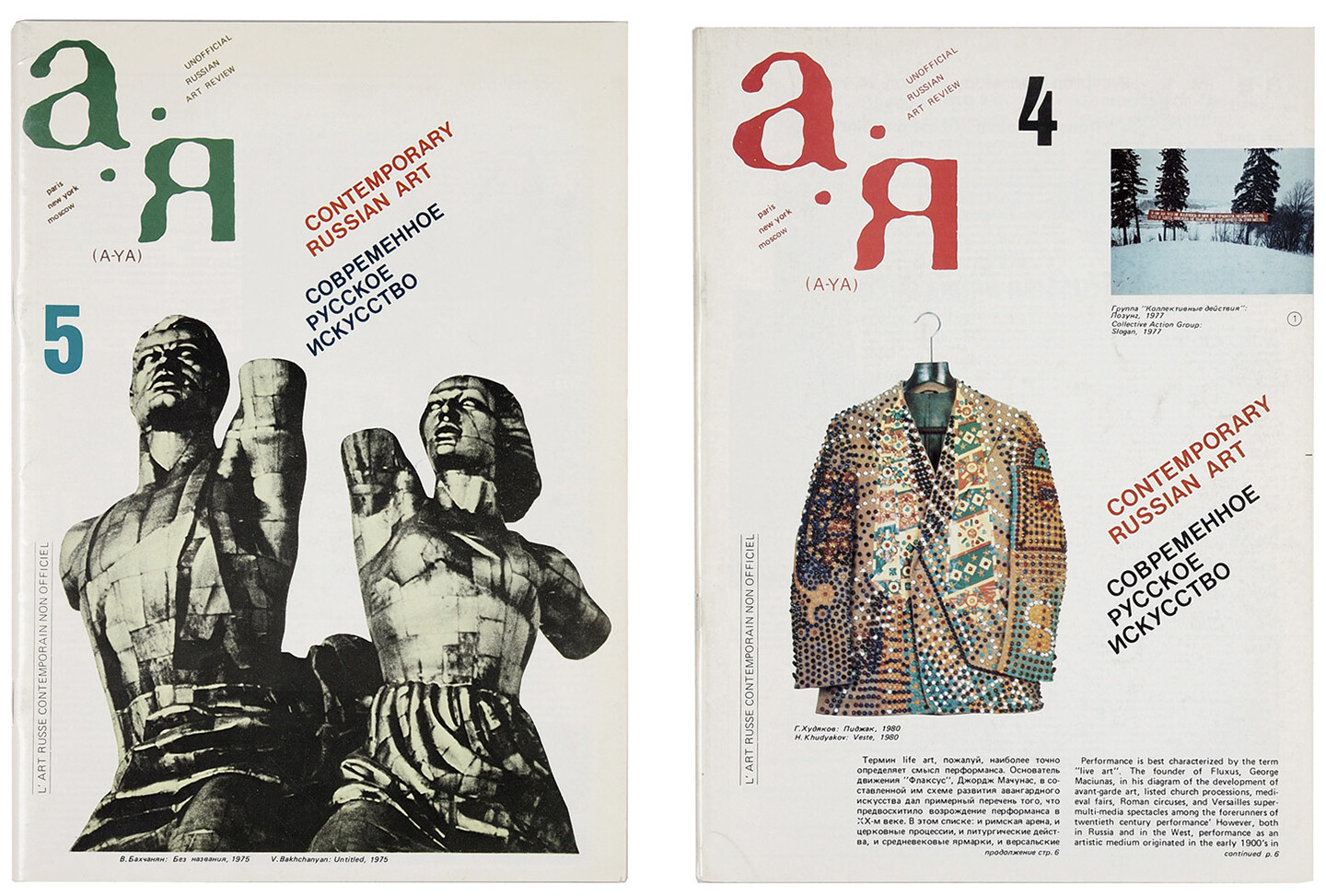

I don’t remember if Boris and I spoke in Russian or in English this first time we met. At the time it was a bit challenging for me to converse in Russian. I left the USSR with my parents in 1981, at the age of thirteen, and did all my studies in English in the US. While I could hold a simple conversation about basic things, speaking about art or theory in Russian was difficult. Boris was very patient and supportive of my gradually becoming more fluent. I suspect one of the reasons I eventually regained the language was due to his encouragement. By coincidence he also left the USSR in 1981, although in very different circumstances—while my family voluntarily emigrated to the US, he was forced to leave the country. I remember the story well: following the publication of his essays on Moscow conceptualism in a Parisian Russian-language journal called А-Я, the KGB asked him to come in for an “interview.” He recalled that the agents seemed quite tired or uninterested, as though after many decades of ideological zeal, they were finally burned out. They were very interested in his sweater for some reason, which made him think they might have expected a bribe. But he didn’t want to part with his sweater. The interrogators also requested that he publicly repudiate his published texts, which he refused to do. So they suggested two options: leave the country or go to jail. Boris chose the former and left for Germany.

Boris had actually been born in Berlin, in 1947. His father was a prominent Soviet electrical engineer who restored electricity to East Berlin following the end of the war. I remember some of my German acquaintances being very impressed by his command of the German language. With Nabokov among the few exceptions, it’s rather unusual for a Russian writer to write in other languages, perhaps due to the particularities of Russian. But Boris writes equally well in Russian, German, and English.

Following our initial meeting in Mexico, we met for lunch in New York. Boris kindly gave me his Gesamtkunstwerk Stalin book, in English, and it totally blew me away. Unlike most Western art historians who espouse the narrative of a certain disruption and amnesia separating a more utopian, early avant-garde from postwar artistic practices, Boris sees the avant-garde in the USSR as a continuous arc that, in a sense, engulfs and devours society, and which even includes the radical state policies of the Stalin period. It’s a very provocative proposal that nevertheless rings true to me.

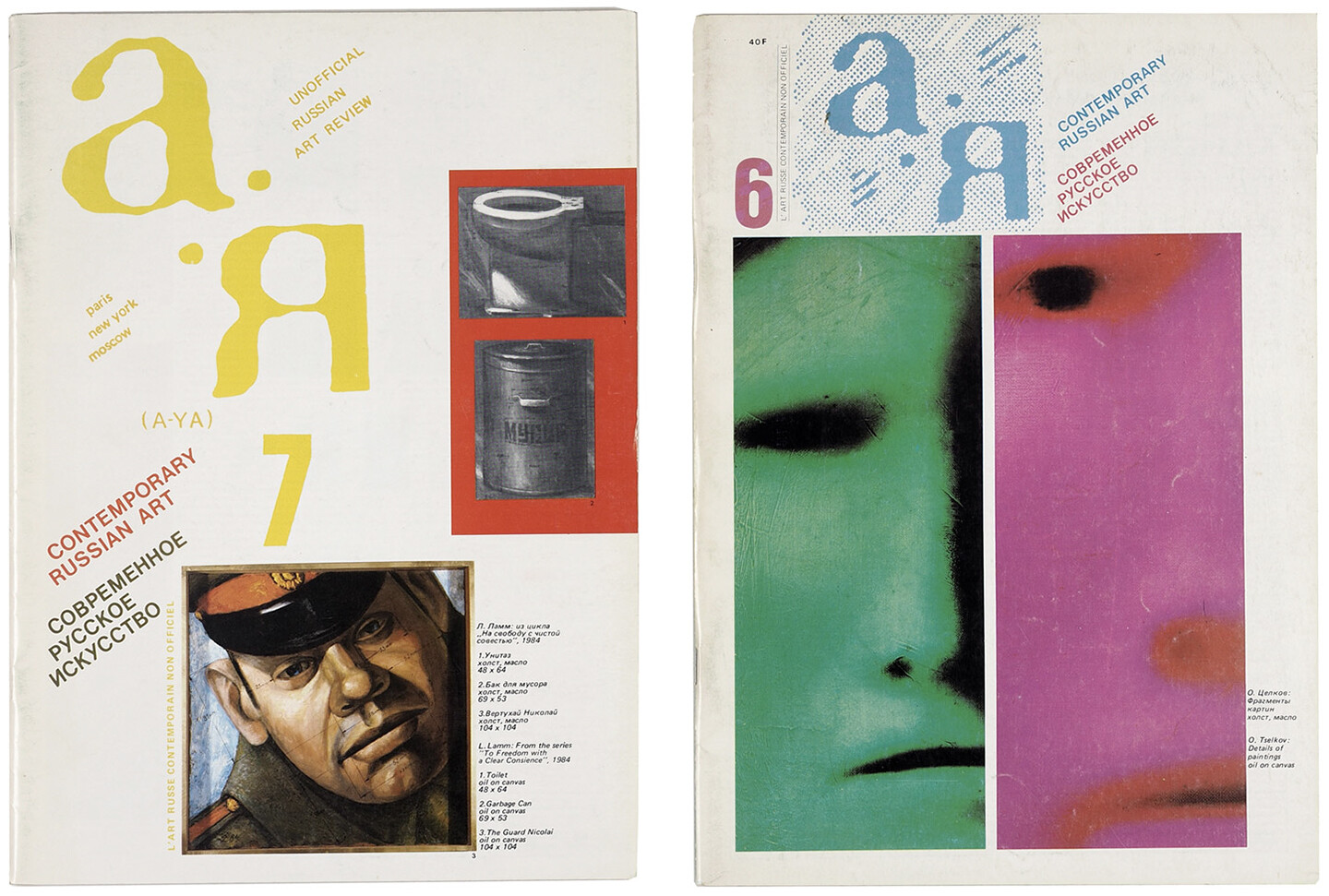

Previously, in New York, I had studied with some of the Marxist art historians who came to prominence in 1980s, like Benjamin Buchloh, Rosalind Krauss, and others who belonged to the October journal circle of writers. While their work and ideas were very much grounded in and made use of the Soviet avant-garde, it seems that none of them learned Russian in order to read primary texts, artists’ writings, and so forth. So, I think they constructed a narrative of what that period was in the USSR as an idealized view from the West, in many ways oversimplified and much flatter in comparison to the paradoxical complexity of that era and its artistic practices, ideologies, and the beliefs of its protagonists. This, in turn, led to a kind of a misunderstanding of what this art was. Boris mentioned to me that when he first started to meet some of his colleagues in the West, it made him feel like a Martian. Imagine a whole industry of academics writing books about canals on Mars. Suddenly, a Martian arrives on earth and says: Sorry, but there are no canals on Mars! And so, in a polite yet sinister way, all these colleagues would ask Boris when he planned to go home—which he couldn’t do even if he wanted to.

Illustration for Mars and Its Canals by Percival Lovell, 1906.

Around this same time, I was invited to cocurate Manifesta, a biennial of contemporary art meant to take place in Nicosia in 2006. Our proposal was a bit radical: we planned to replace an exhibition of art with an experimental art school, and to make it a fully discursive project rather than an exhibition. I invited Boris to be a part of a core group of artists and theorists who would develop the curriculum for this school, and he came up with an incredible seminar called “After the Red Square.” At the time he was finishing his book The Communist Postscript and this seminar was in some ways a condensation of his ideas on the postcommunist condition. Then the biennial was abruptly cancelled: the Greek-Cypriot government, the official host of Manifesta, decided that it was not in their political interests to host an international project that included Turkish-Cypriots in a meaningful way. I spoke with Boris and other participants, and we decided to realize our project independently in Berlin.

We rented a small cement building adjacent to a supermarket in a part of East Berlin formerly called Leninplatz, renamed after Unification to United Nations Plaza. It used to have a gigantic nineteen-meter-tall statue of Lenin. In the mid-nineties the statue was removed and buried in a garbage dump. Boris’s seminar ran for two weeks and included artists and thinkers from Lebanon to China and other countries with a significant history of communist movements. At a certain point we had an emergency. There is a Russian artist who is notorious for physically assaulting other artists, curators, and philosophers as a sort of “performance,” and we learned that he had arrived in Berlin with a plan to disrupt the seminar. Boris had had an unfortunate encounter with him in the past, and while he was not scared, this artist nevertheless had very troubling ideas: he believed that there were only two people whom it would be appropriate to murder as a “work of art”—one being Kazimir Malevich, who was already dead, and the other being Boris Groys. Some years earlier, he attacked and defaced a Malevich painting at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and spent a few years in a Dutch prison. Understandably, we were very concerned and hired security guards for the seminar, which looked extremely strange. We gave them photographs of this artist with instructions to deny him entry, but he still somehow got in. I remember noticing him in the audience and asking Boris if we should cancel, but he wanted to continue. A couple of students who were not intimidated by physical violence moved closer to this artist in case he tried something. In the end it was more of a sputter than an explosion: he did try to disrupt the talk by cursing, accusing everyone in the room of being hypocrites, and spitting on the floor around him, but no more than that. And when he tried to move closer to the speakers, we escorted him out of the building. He did not return, and the seminar continued.

Workers dismantle an outsized sculpture of Lenin by Nikolai Tomsky in Berlin, November 13, 1991. Photo: Andreas Altwein

Perhaps the most important intellectual gift I received from Boris was an introduction to the philosophy of cosmism. At first, I couldn’t believe it was true. Sometime around 2012 I met Boris for dinner, and he started telling me about some strange events that occurred in Moscow in the mid-1920s: there was a mysterious, government-mandated Institute of Blood Transfusion where researchers tried to find a cure for aging and death by exchanging blood between older and younger people; there had been a plan to open blood banks throughout the Soviet Union so that, through these blood exchanges, a kind of literal “brotherhood” would be achieved across the diverse populations of the USSR; Malevich’s Architectons were in fact not models for terrestrial architecture but designs for spaceships and orbiting cemeteries in which the corpses of the dead would be preserved in the zero gravity and absolute cold of the cosmos until a technology of resurrection could be invented. And other such things.

To be honest, I thought he was making it all up: it sounded more like dark, vampiric science fiction than historical fact. However, a few months later I was asked to do an interview with Ilya Kabakov, who unexpectedly told me similar things. It made me very curious, and when I investigated further, I came across a collection of writings by Nikolai Fedorov, the nineteenth-century librarian from Moscow credited with originating the philosophy of cosmism. The book, called The Common Task, was a complete revelation to me. The ideas were incredible and very far ahead of their time, envisioning life and society as a fully planetary, regulated phenomenon in which violence, private property, capital accumulation, exploitation, and alienation are replaced by the universal task of preserving and restoring life through technological means. In short, the main idea of cosmism is deceptively simple: evolution is incomplete because we are mortal and we should focus all of the productive, intellectual, and organizational forces of society on a single task: to defeat death, resurrect all our ancestors, and learn to live in the cosmos (because our planet is too small to support a massive population of resurrected, immortal people).

While Fedorov was a deeply religious person and far from a socialist thinker, his ideas, articulated around the 1860s, are similar to communism in many ways, albeit with one important difference: as Boris points out, communism demands infinite sacrifice from the generations of people who are to struggle towards achieving it. These sacrificial generations will get nothing for themselves in return, except the dream that future generations will live in justice and utopia. Cosmism, on the other hand, offers a promise of material resurrection and thus physical participation in the immortal society of the future for everyone who has ever lived. In this way, each one of us has a personal, tangible incentive to participate in the project of cosmism.

Although Fedorov didn’t publish his writings during his lifetime and didn’t teach formally in a public institution, his ideas did somehow circulate and spread. He had some correspondence with Dostoyevsky, and Tolstoy used to visit him at the library to discuss his ideas. Seemingly, these fantastical ideas managed to enter the work of a whole generation of artists, writers, scientists and other thinkers, to the extent that even without any direct link, one can still sense the imprint of Fedorov’s ideas on the thinking of so many advanced practitioners from that period. Following the October Revolution, cosmist ideas became particularly resonant, probably because their radical materialism dovetailed with aspects of Marxism, and maybe because in a radicalized, revolutionary society that had suddenly abolished private property, nothing seemed to be impossible or out of reach—not even space travel and immortality.

Deathbed of Kazimir Malevich, 1935, Leningrad, USSR.

From 1917 onwards we see the emergence of biocosmism-immortalism, essentially a continuation of Fedorov’s thinking without its religious dimension. Propagated by such figures as the anarcho-futurist poets Alexander Svyatogor and Alexander Yaroslavsky, biocosmism even produced a small political party that advocated for a universal right to rejuvenation and freedom of transportation in cosmic space. Cosmism of this period also included a roster of amazing scientists such as Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the self-taught mathematician credited with founding the science of rocketry; Alexander Chizhevsky, the inventor of space biophysics, best known for his study of the physiological and psychological effects of solar cycles on human history and society; Vladimir Vernadsky, the originator of radio-geology, who wrote eloquently on the “noosphere,” a sphere of human reason encompassing our planet; and many others.

The work of nearly all advanced practitioners of the artistic avant-garde, from Malevich and Rodchenko to Eisenstein and Meyerhold, can be perceived through a cosmist lens. A particularly interesting, lesser-known figure is Vassily Chekhrygin, a painter and writer who died very young but left a vast legacy of artworks and writings quite literally illustrating Fedorov’s ideas of resurrection, immortality, and the cosmos. Most of these works and texts have never been translated into English, or even published in Russian, in part because these ideas were suppressed in the USSR following Stalin’s purges of the 1930s. One important project I did jointly with Boris was a large-scale exhibition related to cosmism at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin in 2017, along with a companion anthology Boris edited of translated texts by key cosmist artists and authors, including many mentioned above, that MIT Press published in 2018.

According to Vsevolod Meyerhold, biomechanics teaches the ability to turn chaos into well-ordered cosmos.

Over the past decade or so, I’ve made seven films based on cosmist ideas. I always think of Boris as the primary viewer for these films, and in a sense, as their most important audience. This is not only because of his deep knowledge of cosmist philosophy, but also because of his keen understanding and appreciation of art. Many scholars, theorists, and philosophers I know have a slightly oblivious or even condescending relationship to art. Most acknowledge its social or historical importance, but I have a nagging feeling that, maybe because they deal primarily with ideas rather than things or images, they perceive art as a more basic or even base practice compared to “pure thought.” Consequently, most of them don’t really see or understand art.

Recently I attended a talk by a German scholar who has spent his entire professional life researching cosmism. He is now in his seventies, and has been preoccupied with cosmism for nearly half a century, since his student days. He is a “cosmism skeptic”—adamant that there is no such philosophical or intellectual movement because, according to him, all its various protagonists contradict each other in paradoxical ways and no consistency of ideas gives it coherency. For him, it’s a kind of a hoax. But I realized it’s actually a very tragic situation for a person to give cosmism so much of his life’s time and energy, really struggling with it, only to now doubt its very existence—mainly because he is unable to see the beauty of its reflection in art, cinema, poetry, music, literature, theater, architecture, and so forth.

Boris has been very close to artists ever since his student days and, while I hesitate to think of him as an art historian or a curator, his insight into art and its practitioners is unprecedented for a theoretician. Maybe this is why the Gesamtkunstwerk Stalin book he gave me years ago was so important for me in seeing the relationship between the incredibly complex trajectory of the Soviet avant-garde and the brutal velocity of dictatorial power: the total work of art that the USSR briefly embodied, and where I came from.

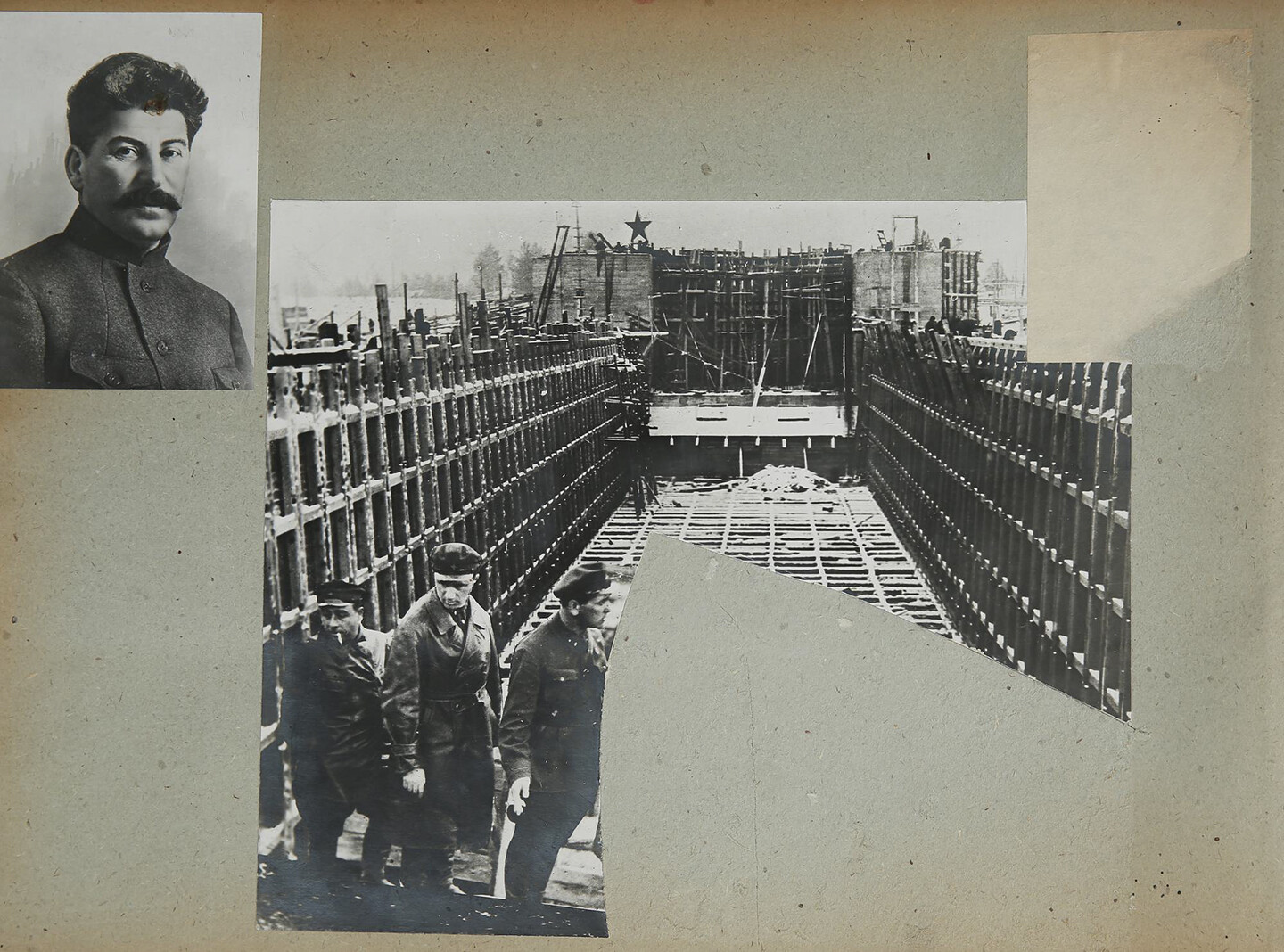

Alexander Rodchenko, Agitkost album, Belomor Canal, 1934. The canal was built with the forced labor of political prisoners, more than twenty-five thousand of whom died during its construction.

A couple of years ago Boris shared an unusual text with me, a kind of script for a film or TV series based on cosmism that some Hollywood producer convinced him to write. It’s not so much a developed script with scenes and dialogue as a rough, conceptual treatment: a story, or even a kind of meta-story. It is set in a future in which the senior curator of the struggling State Museum of Immortality, Ilya Gordon, entrusted with the most important task of preserving and resurrecting the dead, is approached by a mysterious, wealthy patron through his beautiful female associate, who proposes a public-private partnership. Here is how Boris describes the museum:

The museum system was totally restructured, and all the museums and archives were turned into immortality museums. After a person died, his or her body was cryogenized and put into a special container. The container was installed in a room designed to look as if this person still lived in it. The room contained photos and other documentation that were related to the dead inhabitant of the room. The body was preserved, with the goal of its eventual repair and resurrection. The documentation and the general aesthetics of the room were used to restore the personality and individual identity of the deceased: his or her taste, way of life, and familiar environment. In other words, the Museums of Immortality functioned as a democratized version of Egyptian pyramids.1

As the story progresses, it becomes darker and more sinister: the public-private partnership opens the Museum of Immortality to sexual orgies, various satanic rituals, blood sacrifices, and eventually cannibalism: they eat the corpses they were entrusted to preserve and resurrect.

I have often wondered why Boris wrote this script. One of the very important literary works in the cosmist oeuvre is a science-fiction novel published by the Marxist theorist and scientist Alexander Bogdanov called Red Star (1908). The title refers to the planet Mars rather than the communist red star, although it is often described as “the first Bolshevik utopia” because Bogdanov also happened to be the cofounder of the Bolshevik faction of the Communist Party in Russia. Personally, I would not describe it as a utopia: in the novel, the Martians, who have already reached a high level of socialism on their planet, kidnap an earthling and lure him to Mars, where he learns that despite their advanced society and the superior technology by which they attained near immortality, their planet is actually dying and they plan to colonize earth and subjugate humans. While there are no specific overlaps in plot or narrative between Bogdanov and Groys, I feel a similar texture in these works. I also think that what has always mattered in Boris’s work is something shared with Bogdanov (and Malevich, Bely, even Kabakov), which is the possibility to go outside his own time and way of seeing. This becomes a method by which he is able to transcend his era, his situation, his existence.

I once asked Boris if he would allow me to make this film, but he demurred: apparently at the time they were negotiating producing it as a serial for a streaming platform, or something like that. As far as I’m aware that didn’t happen, so maybe there’s still a chance it could become one of my films. I really hope so, and there’s plenty of time: eternity. Immortality and Resurrection for All!

Boris Groys, “Becoming Immortal,” Cosmic Bulletin, 2020 →.

A version of this essay will be included in a forthcoming edited book on Boris Groys titled Total Art, Total Theory: Essays on Boris Groys.