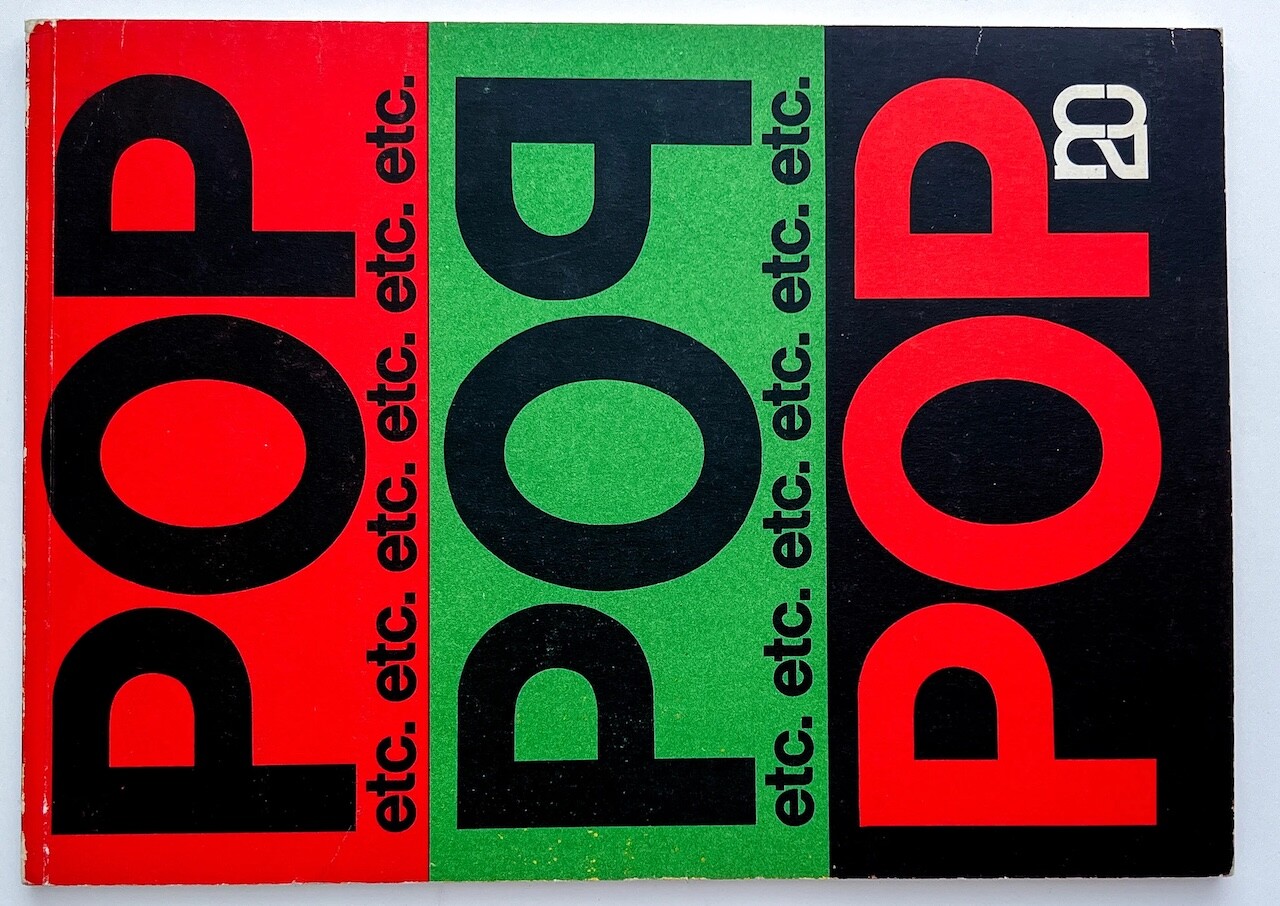

Cover of the exhibition catalog for “Pop, etc.,” Vienna, 1964.

In 1964, while in Vienna for a conference, a delegation of Soviet philosophers happened upon “Pop, etc.,” an exhibition of pop art featuring works by Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein that was held at the Museum of the Twentieth Century (now known as the mumok, or Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien). Among members of the Soviet delegation was the Marxist philosopher Evald Ilyenkov, who subsequently recorded his impressions in an exhibition review titled “What’s Through the Looking Glass?” (Chto tam, v Zazerkal’e?). An excerpt of this review appears here for the first time in English, translated by Trevor Wilson. This traveling exhibition became Ilyenkov’s trip “through the looking glass” into the inverted world of the capitalist West. There, Ilyenkov writes, art had seemingly committed suicide, having sacrificed concrete form in its pursuit of the fetishization of things.

***

In the fall of 1964, during a trip to the Philosophical Congress, our delegation found itself in Vienna on the exact same day as the opening for an exhibition of pop art that had arrived from America. We had all heard something about “pop art,” read something about it, and so we had some general idea about the individual masterpieces of this movement based on faint clichés in the newspapers. Yet since we had become accustomed to trusting our own eyes more than “a rumbling of rumors,” we all decided as one to not miss a chance to get better acquainted with this “pop art” in person, without intermediaries.

[…] We then reflected for a long time on what we saw. The spectacle gave quite a bit of food for thought and discussion. In some respects, our judgments happily aligned, in others less so, yet one thing was sure: the exhibition made a strong impression on everyone. I am judging for myself and from the agitated tone in which we exchanged opinions. I cannot remember whether anyone reacted to what they saw with impassive reflections. That only came later, although we all still belonged to that class of philosophers called to not cry, not laugh, but to understand.

As I do not feel I have the right to speak for others and in their name, I will merely share my own, perhaps entirely personal experience of that day.

Entering the halls of the exhibition with a feeling of totally understandable curiosity, I felt prepared in a rather ironic way. Such a setting for experiencing pop art seemed to me, based on everything that I had read and heard about it, entirely natural for any average person. Yet already after ten minutes, this ironic and mocking apperception, being “a priori” yet obviously not at all “transcendental,” was swept away and demolished entirely, through a deluge of immediate impressions that assailed my psyche. I suddenly realized that something wrong was happening in my poor mind, and, before I was able to make sense of what was happening, I felt terrible. Literally physically terrible. I had to cut short my tour and exit for fresh air, onto the streets of the sedate and old-fashioned beauty that is Vienna. Naturally, in these moments I did not attempt to theorize, but I immediately understood one thing: my nerves could not take the stress and gave out. The barricade of irony behind which I had hidden myself from pop art, “abstraction,” and other such things of modernism could not bear this onslaught of impressions and came crashing down. I had not bothered to prepare in advance any other line of defense, and these physically foreign images, foreign to me to the point of hostility, all squeezed together, forced their way into my psyche, unceremoniously took residence inside of it, and I was unable to handle them.

So I sat on the steps of the entrance and smoked, unsuccessfully trying to conquer within myself this unpleasant feeling of dejection, of confusion, and of anger at my own nerves.

When I finally became capable of expressing myself articulately, then, I remember quite well, I said, “It feels to me as though a good friend has fallen in front of a tram right before my eyes. I cannot look at his entrails smeared all over the tracks and asphalt.”

Now, several years later, I cannot find any other words that might more accurately describe the state which the exhibition had brought about in me.

An interpreter standing next to me, carefully taking stock of my confused face, said, “I understand how you feel. You are simply not used to it. It’s hard to immediately wrap your head around it.”

“Do I need to?” I asked her. “Is it worth getting used to?”

She thought for a moment, shrugged her shoulders and didn’t answer at first. Being very sophisticated and intelligent, she clearly had her own articulate views on pop art, on abstraction, and on many other phenomena of modern intellectual culture, yet she was tolerant enough even of those that did not conform to her views.

“You are, of course, right,” she said a bit later, “to disapprove of all of this. It really is 90 percent rubbish and charlatanism. Here in Vienna, we also understand that. Yet there’s nevertheless something here that, it seems to me, you might not notice. Some things that are really, in their own way, quite accomplished. Maybe even 10 percent in total. And that’s a good thing. Here, for example, this composition made of electric lamps and tin soldiers …” And she began to explain to me, entirely sincerely and calmly, without any particular excitement or any particular desire to impose her opinion upon me, why and what she liked in this composition that was exquisite in its own way. She found a certain sense of taste in it, a mark of imagination, and many other qualities. Why not then marvel at it, if it had been in fact executed artistically and elegantly?

“It is not often in general that one encounters real skill. And is that not the most important thing? What difference does it make if it’s pop art, abstraction, or figurative painting?”

So she posed a question to me that, at the time, at the entrance to the exhibition, I dared not answer. Really, what was the most important thing in art? What exactly makes art art? I saw no way of answering this in two words or less. Nor did I have any desire whatsoever at that moment to set sail into the oceanic depths of aesthetics, lapping on the shores of realism, the shores of surrealism, and the shores of pop art where we had only just been. And so I remained silent.

At that very moment, my philosopher colleagues, whose nerves proved stronger than mine, were having a very curious conversation with the curator of the exhibition. Having returned to the hall, I began to listen as the Austrian professor, calmly and patiently, carefully choosing his words, fought off an attack from one of our philosophers: “No, you are deeply mistaken. This is not gibberish, not a travesty, not charlatanism. It really is art. And perhaps even the only kind of art possible in our time.”

At first, I decided that I would listen to this latest variation on the notion of an artist’s right to see the world as he pleases, but what I heard next made my ears prick up.

“Yes, really art. A dying art. The death of art. Its agony. Its death throes. Art has fallen under the iron wheels of our civilization. It is a misfortune. A tragedy. And you scoff at it.”

I cannot guarantee that I am conveying the words of the art historian from Vienna with stenographic accuracy. I can grasp spoken German only with some difficulty, something which moreover already has taken nearly four years. Yet I can vouch for the meaning of his words—this is also how the others understood them.

“It is art, my sirs, art and not charlatanism. Art, before your very eyes, is taking its life in suicide. Suicide, my dear philosophers. It is sacrificing itself. In order to at the very least force us all to understand the path we are taking. It is illustrating what we ourselves are turning into. Into junk. Into things. Into dead things. Into corpses. And until now, you didn’t understand this. You find it to be a circus, a travesty, a magic trick. Whereas it is in fact agony. And a most genuine one. A mirror which shows to us our own proper essence and our future. Our tomorrow. If everything goes the way it is going. Alienation …”

Someone began to object to the professor, that tomorrow does not necessarily need to be so grim, that we imagine such a tomorrow entirely differently, that alienation is alienation and charlatanism is charlatanism, and that the creators of pop art didn’t resemble unfortunate suicide victims, but rather resembled successful business men [gesheftmeistery], and so on and so forth.

“Perhaps the most tragic thing consists in the fact that they themselves don’t understand it. They are not aware of what they are creating. They themselves believe that they have found a solution to the dead-end of abstraction, believing that they are returning an objectivity to art, a concreteness, a new life. But this is not about them. This is about Art. They can get away with not understanding. But we, sirs, we are theoreticians. We are obligated to understand. Our civilization is moving toward suicide. Art understands this. Not the artists. Art itself had thrown itself under the wheels. So that we see it, become horrified, and understand. And do not marvel at it. And do not mock it. Both of which are beneath intelligent people. Take a better look.”

I once more looked around the hall. Above the entrance, as an emblem, was a massive sheet of photo paper, about three by four meters. From afar, it is a great black and white surface, while up close the eye discerns hundreds of the exact same image placed in rows—prints of the exact same negative. A woman’s face, the very same one repeated hundreds of times. Hundreds of poorly made photographs, such as are made by photo artists to obtain their official certification … And the person who is viewed a thousand times in this way is the well-known Mona Lisa, the very same “Gioconda.” As a result of this annoying, mechanical reproduction, the face has lost what we call its “individuality.” And the famous smile has lost any semblance of mystery. The mystery has been wiped clean from the face by the corrosive chemicals of a talentless photographer. The smile has become deathly, frozen, unpleasantly artificial. The professionally acquired smile of an aging model who smiles simply because that is what’s expected of her. But not even this is important, for the face and the smile here play the role of a brick in the bricklaying of the “composition.” A Mona Lisa like any other. While Mona Lisa disappears …

I look at her and I think with regret: “Now, if I ever get the chance to see the real, living ‘Gioconda,’ my meeting with her will probably be poisoned by the recollection of this spectacle.”

For a second, a thought crossed my mind: what about Perov’s misfortunate Hunters and Vasnetsov’s Bogatyrs, which had somewhat recently come to make regular appearances in beer halls and train station canteens? After all, you poor things, too, have become debased in just the same way. One had become sick of you, too, trivialized you to such a degree that one feels nauseated even looking at you. Worse even than the Dance of the Little Swan … Well, whatever, more on that later. Not everything all at once. It’s just clearly no accident that the sorrowful state of the “pop art” exhibit recalled this sad set of circumstances.

Next to this sadistic, murdered “Gioconda” was a toilet. That very same textbook toilet that must be mentioned, alas, in every story told about pop art. A real, usable toilet, brazenly offering its services. Yet underneath it is a text through which it is to be understood that, in this instance, it is designated to serve aesthetic, intellectual needs. Here it serves merely as an object of disinterested, pure contemplation. Try to make sense of it: Do they want to uplift what is low, or degrade what is highbrow? Where is the top and where is the bottom? Everything in the world is relative …

In the corner of the hall, a gnashing sound can be heard from some poorly adjusted cogs. The curator of the museum has turned on a switch and some sort of sophisticated construction has begun to move, to rush about, and to jerk its joints around. Overhead, in a nickel cup-slop bowl is a real human skull. The slop bowl with its skull slowly rotates, shaking. Directly in front of it, strung on steel rods, two disgustingly real replicas of eyeballs are also rotating in different directions. Lower, jerking this way and that by wires, are two fists in cloth gloves. On the floor are two shoes. A zinc water cistern serves as the composition’s skeleton, with a faucet placed in an appropriate spot. There is also explanatory text. Yet it is clear without the text who and what all of this depicts. Here lies man. His image and divine likeness, just as the pop artist sees it. Whoever finds it funny, I don’t. Do you find it funny?

And as one proceeds further, piled on top of one another are soup cans, wire coils, electric lamps, tin soldiers, a bathtub, tube-like entrails from some kind of household appliance, and so on and so forth of this kind of thing. From the wall, a roughly done up beauty bares her teeth from a billboard, with some kind of burlap hanging down …

At some point, everything here became so sickening to me. And only later did I realize why.

This kind of art achieves its desired effect not through skill, but through mere numbers, in mass, brazenly. If you see just a single masterpiece of this kind, it would hardly invoke in you any kind of emotions beyond bewilderment. This is probably why photographs of individual successes within the “modern” avant-garde visual arts, even those of wonderful technical design, do not and cannot give you any sense of what exactly “pop art” is.

Individual pieces of pop art, clearly, are powerless to thwart any natural resistance in the psyche of a man who possesses the most elementary level of artistic taste.

It is an entirely different case when these pieces, concentrated in the hundreds and thousands into special halls set aside for them, inflict a single, massive blow on the psyche: they beset you from all sides, pile onto you, press against you, come crawling out of the corners and the woodwork just like the evil spirit in Gogol’s “Viy”—some remain eerily silent, others gnash their iron teeth and aim to catch you in their deathly hands. At this point, any life-saving sense of humor may as well abandon you, and you might find yourself with no time for irony. Against your will, you find yourself reflecting upon it seriously. “You find it to be a circus, a travesty, a magic trick. Whereas it is in fact agony. A most genuine one.”

I don’t believe that this elderly professor from Vienna was a Marxist, let alone from the ranks of “dogmatics” who stubbornly refuse to accept any new trends in art. He may have been entirely a Catholic, or a neo-Hegelian, or an existentialist. I don’t know. In any case, he was a smart and intelligent man accustomed to reflecting on what he saw. In the form of pop art, the death of art was made so obvious that it was now understood by both atheist and believer.

“Art, before your very eyes, is taking its life in suicide … Agony, death throes …”

Try as I might, I was unable to see this—the agony—in the mass accumulation of pop art objects with bad taste. I could see only the entirely cold and lifeless corpse of art where the professor was still remarking on differences in its convulsions. Perhaps his eye is more professionally perceptive than mine, and he could see flickers of a dying life where I saw nothing at all.

Suicide? Perhaps. In this regard, I felt internally completely in agreement with the philosopher. Except that, probably, this had already happened earlier. Either at the stage of abstraction, or at the stage of cubism. At that point, one could still detect the spasms of a dying and, thus, still living organism. Whereas the pop art exhibit already gave the impression of an anatomical theater. An oppressive, frightening, and grim impression.

“The iron wheels of our civilization … Our civilization is leading to suicide … Alienation …”

This is much more plausible. I could agree with it. These are necessary remarks that ought to be made by any Marxist.

Indeed, it is clearly necessary to view pop art as a mirror, reflecting to the citizen of this “alienated world” his own image. That image into which this thrice-mad, upside-down world turns man. A world of things, mechanisms, devices, a world of standards, templates, and lifeless models—a world made by man, but one now beyond the control of his own conscious will. An incomprehensible and uncontrollable world of things that recreates man in its own likeness and image. A dead corpse that has become a despot over the labor of the living. A world in which man himself turns into a thing, into a dummy which is jerked about on wires in order to get him to perform the necessary, convulsive movements for the “composition.” Pop art is a mirror for this world. In this mirror, it is the human that stands before us.

A human being? Could you be more precise, more concrete?

It is a human being who has made peace with his fate in a world of “alienation.” A man thoughtlessly and passively accepting the world as it is, intimately in agreement with it. A man who has sold his soul to this world. For trash. For a soup can. For a toilet.

This man should not then be surprised and get upset when art suddenly begins to depict him as a soup can. Or as a toilet. As a pyramid of trash. As pop art.

Such a man cannot but look this way in the mirror of art. This is probably what the sad art historian in Vienna meant when he said that “pop art” may well be “the only kind of art possible in our time.” Indeed, if one takes bourgeois civilization as the “the only kind of humanity possible in our time,” one must agree with him out of necessity, however unpleasant, and then take pop art as the inevitable conclusion to the development of “contemporary art.” Get used to enjoying it aesthetically. Get used to it even if, at first, it disgusts you. After all, man can get used to anything. Especially if he gets accustomed to it gradually, methodically, slowly, step by step, starting with just a little.

First, get used to finding pleasure in a game of different colored cubes. Try to construct your own self-portrait from these cubes. You’ll then feel that you like this self-portrait, and that in contemplating it you get the same sense of enjoyment as you used to in such old-fashioned things as the Venus de Milo or the Sistine Madonna—rejoice. You are already on your way to the goal. Transition next to the dissection of the cubes onto painted surfaces, from planes to lines, from lines to points and dots. Do you feel a sense of freedom, of beauty? You’ll then lose sight of the last bits of old-fashioned rags, the final remnants of abstraction, and you will set your sights upon the most modern form of beauty. The beauty of the toilet. And thus calmly, with the knowledge of having fulfilled one’s duty, submerge yourself in selfless prayer before this new altar, and experience the joy of abnegation.

What’s important is to begin. For this path will lead you toward your goal. Have you accepted seeing a higher beauty in cubes? All according to plan. Know that you, if you yourself are an artist, have made the first bloody incision into the body of art with your own two hands. Know that someone will follow in your footsteps, someone bolder than you. He will draw the next bit of blood, drawn straight from the heart of art. And, finally, the pop artist will arrive. And there will be a cold, still corpse on the zinc coroner’s table of aesthetics.

Art’s suicide really has occurred, in the form and image of “modern” (in Russian, “contemporary” [sovremennyi], in theoretical terms, bourgeois) art. To be more precise, it has been occurring. Slowly, painstakingly, in stages. It is just that it has no appearance or character of heroic sacrifice. This art, through its authorized representatives, has not at all thrown itself “under the iron wheels of our civilization” before viewers, so that they might become horrified and realize what awaits them if such wheels continue on the same tracks. Quite the opposite. Modern art has laid down on these aforementioned tracks with masochistic satisfaction, and has invited all viewers to share in this dubious satisfaction. The fact that artists who have allowed this sad event to happen by their own hand have not realized the real meaning of their actions, and have even constructed all sorts of noble illusions on their account, changes nothing with regard to the objective meaning and role of modernism. Any artist captivated by this broad movement, regardless of what he may think of it and whatever conscious goals he may pursue, has objectively contributed to the murder of Art. Sometimes he may suffocate himself, stifling his own song as it rises in his throat, vaguely sensing that something is bad and not right. It has happened before. Yet this awakening awareness is extinguished by leftist phrases, sometimes even written in Marxist terms. These phrases lull the artist back to sleep and transform him into a willing servant for forces which are in fact naturally hostile to Art and to the artist’s personhood. Forces which nudge both Art and the artist toward suicide. This, too, is a fact. And then they proceed to praise the deceased.

Meanwhile, real Marxists—and not blowhards—had early on already discerned the true—the objective—meaning of modernism. They had never tired of explaining where modernism was going and how it would end. No one believed them. They received as a response: this is “dogmatism,” an inability to see “modern art,” to obtain a “modern viewpoint”… As a result, they got pop artists. Back in Vienna, we all came to a unanimous conclusion: the cleverest thing we could do would be to invite the pop art exhibit to Moscow and place it in the Manege for universal evaluation. Rest assured, hundreds of masterful tirades against modernism could not produce the same effect as viewing this display. Many would lose the desire to play around with modernism, and it would force a serious reflection on the fate of modern art. In light of this instructive display, much would become clearer. And, perhaps, many advocates of abstraction, cubism, and their related movements would turn a more sober eye on the object of their admiration. They would no longer see in it the free-spirited, Dionysian dance of modern art, but instead art’s convulsing spasms—perhaps still alive (in contrast to pop art), but in agony.

If it is true that human anatomy offers a key to the anatomy of primates, then such a living representation of pop art should present the genuine key to a genuine assessment of its embryonic stages, to those not-quite-developed forms which, in abstraction and cubism, cannot be so easily analyzed by a theoretically untrained eye, and can even be taken as something “progressive.” Pop art, in its final form, illustrates the precise trajectory of this progress, and how it will end for art. And for humanity. For pop art is after all a mirror, and not just charlatanism or hooliganism. It is a mirror that reflects the notable tendencies of “modernity.” The very same tendencies of “modernity” that threaten humanity—and not merely art—with rather unpleasant consequences.

Through the aesthetic lens of pop art, one really sees the finale to the development not only of art, but also of man, who has fallen onto the tracks of modern civilization’s bourgeois development and is being dragged along behind with it. This is useful for each of us to realize. And to realize that this means seeing pop art through the eyes of a Marxist. Through the eyes of a communist. From the point of view of Marxist-Leninist aesthetics and the theory of reflection.

This point of view compels us, in particular, to combat first and foremost not pop art or abstraction as such, but the real social conditions which have given birth to abstraction and pop art, and to pop-ism [popovshchina], conditions which are merely being reflected in its own offspring. That same point of view encourages us to see in abstraction and pop art not “modern beauty,” but a genuine deformity in the form of human relations that is reflected in them, the very same form of human relations that is called in scientific language “bourgeois.”

Modernism, no matter which illusions its proponents harbor on its behalf, is entirely, from beginning to end, from cubism to pop art, a form of man’s aesthetic adaption to the conditions of an “alienated world.” A world where dead labor rules over the living, and a thing—or to be more precise, a mechanistic system of things—rules over man. A world either which humanity must overcome, or in which it will perish. Together with the world. Humanity has accumulated enough technical means for accomplishing one or the other solution. In this rather serious circumstance, one cannot but realize what modernism is, and how one should accordingly relate to it. That one can get used to modernism and develop a taste for it is like how one can develop a taste for vodka, which does not follow that vodka is good for you or that it heightens your intellectual faculties. The same can be said of modernism’s effect on the sharpness and clarity of one’s aesthetic “view.”

Understood correctly, in a Marxist way, modernism appears as a mirror. But reflected in this mirror is man deformed by the world of “alienation.” It is no modern beauty to be marveled at, as at Apollo. This is what needs to be understood.