Consider what it is to be concerned with the florescence and efflorescence of this generation’s self-defensive care, its prefatory counterpleasures, which reveal the public intramural resources of our undercommon senses, where flavorful touch is all bound up with falling into the general antagonistic embrace of inhabited decoration, autonomous choreography, amplified music, of which what happens in the yard, or at the club, or on the record are only instances, unless the yard is everybody’s and the club is everywhere, and everything is a recording.

—Fred Moten1

In Alex Wheatle, the fourth film in Steve McQueen’s five-part cycle of films entitled Small Axe (2020), the eponymous character enters the diegetic scene of his life’s narration by walking through a poured concrete volume shaped by antiseptic floors, bordered by institutional walls, regulated by a tempo that rings to the slick echoes of imprisoned bodies laboring at a fraught precipice between self-preservation and “self-actualization.”2 Their resonant sounds in the background of that scene’s unfolding constitute a faint but palpable echo within the great basement hall in Beacon, New York, where McQueen’s infratones pulse urgently directly beneath Cameron Rowland’s Underproduction (2024),3 a work whose artful occlusion and inversion mark a threshold between perceptibility and the position of the unthought.4

Rowland’s “sculpture”5 indexes ongoing emanations of Black futurity in an object whose historical emplacement protected the inchoate soundings of study, unfolding in Black interiors. Their cantankerous pan literally overturns audibility as a praxis of the enslaved, by way of an object echoing a series of acts aimed at nurturing undercommon narrations that secreted the end of slavery back into its fetid presents. In McQueen’s film, Wheatle’s silence—his stolid, wordless withdrawal from the scripture of his forced narration—tracks his horizontal movement through the scene’s opening frames, so that the camera figures Wheatle’s embodiment as an interstitial silence, an intermission coursing along diegesis’s teleological line, continuously syncopating the prison’s Taylorist rhythms.6 Wheatle survives a terrible tempo. His biography is narrated atop his worldlessness as an erasure entered in the logic of institutional inscription. Like much of Black history, Wheatle’s life attains legibility through its iteration in the ledger.7 His life recursively begins in the film as a writing out—a literal de-scription—and it is only in song, in his discovery of reggae and dub, that Wheatle finds his own choral echoing articulation. I hope to listen for such echoes in what follows.

A litany of texts converge at this small postindustrial corner of western New York, at a juncture in Dia Beacon’s galleries that resonates with the neighboring awfully harmonic geometries of Melvin Edwards’s haunted chords, his cascading wire riffs resonating their correlated displacements and expansive reiterations as Rowlands’s anti-propertizing art now enters the precincts of Dia.

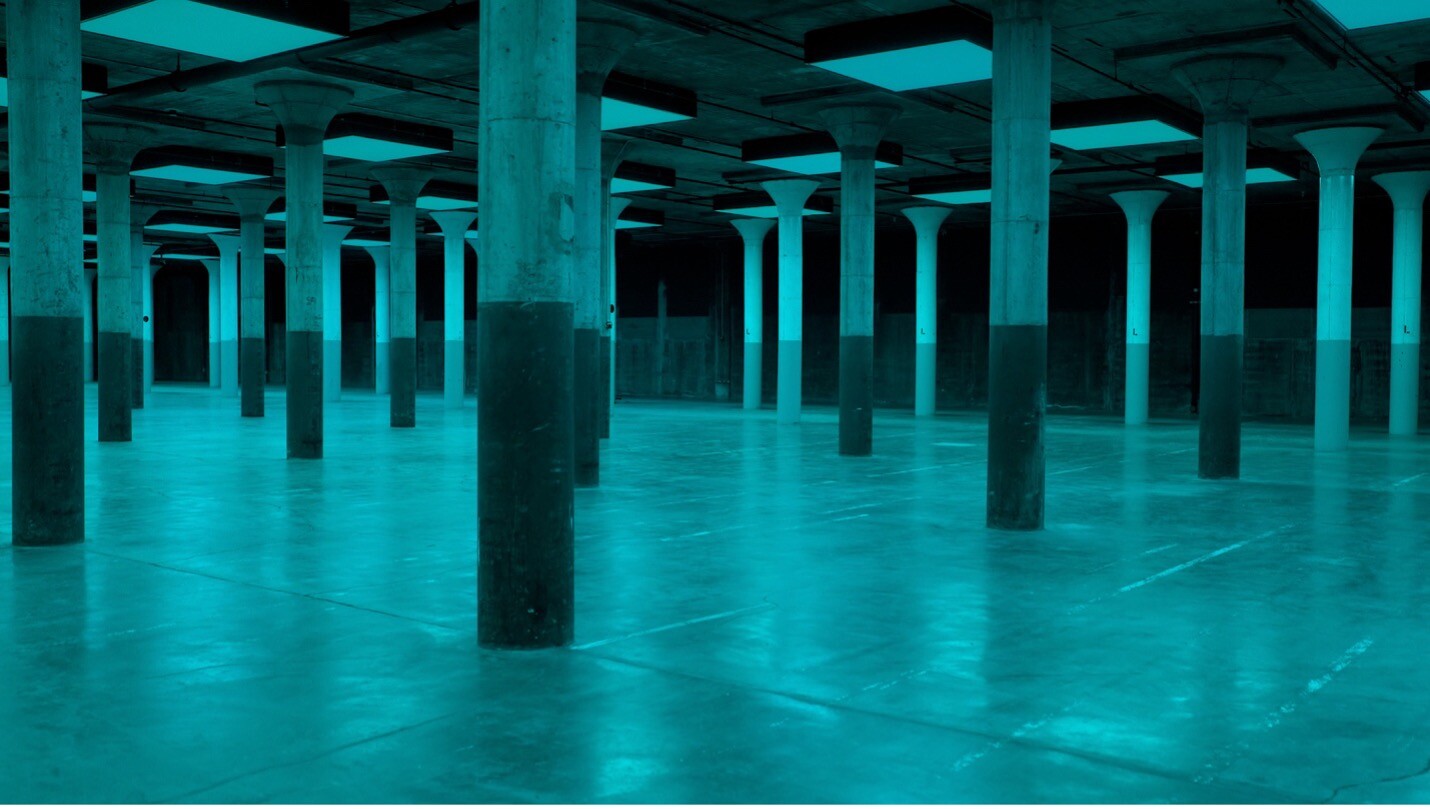

Something complicated is afoot here. In Bass’s (2024)8 sonic emanations, we are given the cyclical iterative rhythms of an insistent tone pulsing under a gridded cascade of oscillating depthless lights—lights that in their near total diffusion and dispersal of the body’s shadow shift the historicity of this postindustrial space. Upstairs, above ground, within the theater of Rowland’s installation, the restrictive rhythms of covenant now resound in Dia’s galleries, and thanks to McQueen, so too does Bass’s dissonant, syncopated enunciation—its musics of muffled speech, and their digressive departure from a point without origin.9 Bass emits a somnolence from its basement space that sprawls with expansive plasticity beneath the wooden floors that bear one third of Rowland’s exhibition “Properties” (2024). Between Senga Nengudi’s pendant vessels, Edwards’s barbed strings, and Rowland’s and McQueen’s installations, Dia’s Beacon galleries are now collectively marked by these distending transformations of the regularizing, racializing frequencies of American industry.

In McQueen’s Bass, the bass itself instrumentalizes its audience as medium, as vector of its own fluvial movements. To enter into Bass’s aural field is to earth and disperse its itinerant vibration. Wherever we hear it, we bear and share its enunciations bodily. Moreover, Bass’s capacity to incorporate its audience as vectors of communicability enlists it in an ongoing act of (re)production, of labor without contract. Within this dematerializing structure, Bass rehearses a blackened condition of sudden availability to conscription into involuntary labor under conditions of (light) prescription, and it does this without imposing upon its audience the corollary and hereditary unfreedoms that echo in the work’s solicitation and imaging of the hold.10 In this, it is a non-sequitur.11

Bass is a resonance one might more easily pass than parse, share than plot, feel than name. It is what Tina Campt describes as “infrasound”—a fugitive, resistant murmuration “often only felt in the form of vibrations through contact with parts of the body.”12 In its irresistible communicability, Bass enacts affectability as a discourse of blackened sociality; it produces a machinic and mellifluous instantiation of miscegenation as a mode of fashioning, of weaving meanings that exceed the strictures of proper naming. Bass performs what Anthony Huberman calls “banging on a can,” in a Motinian echo of a mode of creative response that thinks the material and symbolic dimensions of life musically—a mode of intellection that reads worldliness in and as song.

That very act of banging on a can summons the friendly ghost of David Hammons squarely into the scene of Dia’s ongoing expansion and reiteration of its artistic program, effected here through these newly orchestrated installations of Edwards, Rowland, and McQueen. If the 2017 Met Breuer exhibition “The Body Politic” showed an affinity between the artistic practices of Hammons, McQueen, Arthur Jafa, and Mika Rottenberg, it was that rattling digressive can in Hammons’s Phat Phree (1995–99) that articulated a rhythm of improvisatory wandering, an invisible architecture of spontaneous combustion, which threads through Bass, just as Bass’s blue tones echo both Hammon’s Concerto in Black and Blue (2002) and McQueen’s earlier Blues Before Sunrise (2012).13

Bass emerges in a season in which Dia has welcomed, in linear sequence, the dual interventions of McQueen (at both its Beacon and Chelsea locations), the subtly inimical interpretive engagements with Bruce Nauman offered by Paul Pfeiffer in its ongoing Artists on Artists series,14 and now the inauguration of an installation by Cameron Rowland. In other words, Bass murmurs its rhythms in a season in which non-white speech has again assumed a position of prominent articulation at the core of Dia’s platform.15 Notably, where both Hammons and Nauman enact their repetitively aggressive bangs in such works, the modality of articulation common to Pfeiffer, McQueen, Rowland, and Nengudi could more aptly be described as a sinuous infiltration. Perhaps we might think this broader symbolic and racial moment in Dia’s art history with an eye squarely focused on the inattention so artfully and potently situated in Moten’s trenchant text “The Case of Blackness,”16 and perhaps we might consider the distinctive inflections of this set of practices—figuring them together with the weaves of Edwards and the vessels of Nengudi—within the undulating parameter of Renee Gladman’s iterative, recursively entangled, and infinitely wending lines:

I began the day wanting to bring into convergence three activities of being—what I’d seen, what I’d read, and what I’d drawn—and to say about these acts how they made lines in the world that ran alongside other lines, and how all these lines together made environments of the earth, where I could put my body and you could put yours, and these would be lines always entwined because there was little if anything you could say or make without calling forth other lines, and this was how you knew you were where you were and the ground was worth cultivating and that there was life beneath the ground.17

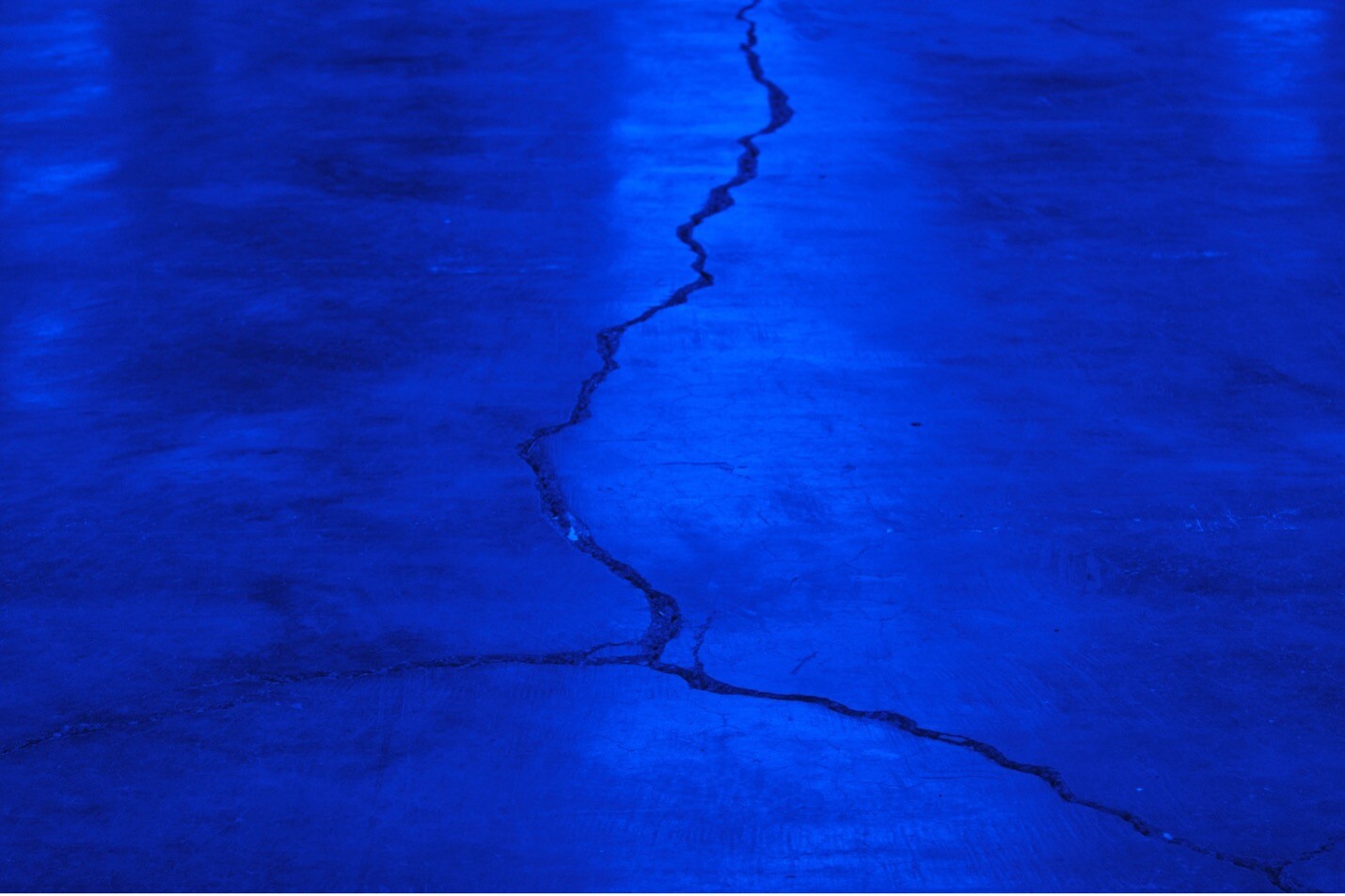

Easement boundary line of Cameron Rowland, Plot, 2024, photographed November 2, 2024, Dia Beacon, NY. (See caption in footnote 18.)

Rowland’s entire practice is testament to this last irreducible line: “there was/is/has been/will forever be life beneath the ground”: this is their Plot (2024),18 their tripartite intervention within the precincts of the Dia Art Foundation, and within its Beacon grounds.19 If we can approach Rowland’s work actively grappling with our ongoing imbrication in the irremissible debts of native dispossession, if we can arrive at such work freighted with a sense of the weight of racial slavery’s indispensable role in the formation of modernity, if we can reckon with what Kathryn Yusoff incisively describes as “this conversion of earth through the grammars of geology” into profit, into property, through a confluence of material and epistemic violences that “enacted a world-building and world-shattering” project whose ravages have been of an alarmingly consistent extremity, yielding to white supremacy an immense megastructure of racial capital continuous within our present afterlife of slavery,20 then we might grasp the terrible beauty of Rowland’s plot.21 Here, again, Gladman’s fractal lines course umbilically through McQueen’s fluvial sound, Edwards’s stringed instruments, Nengudi’s flavorful bodies, and Rowland’s upturned pan:

… where all at once the lines in the world head for the periphery, and each departure is violent and each exploding site is a center with a micro-architecture inside that pulses like all centers pulse, responding “to the megastructures of the previous layers,” each center being a book burning at the core of the earth.22

In Rowland’s recourse to the contract,23 to the rubric and stricture of the ledger, there is also an awful, beautifully inverted line drawing together, in utter involution, the categorical distinctions between earth, edifice, institution, and the afterlife of slavery.24 Through these documentary interventions, Rowland fathoms a set of “languages having to break in order for [enslaved] words to appear, to flow like they’re searching for something, illuminated from within,” to borrow from Gladman. In consonance with Marina Vishmidt, we might think this as infrastructural, and not institutional, critique, attending to the ways in which Rowlands’s mode of operation moves from “a standpoint which takes the institution as its horizon, to one which takes the institution as a historical and contingent nexus of material conditions amenable to re-arrangement through struggle.”25 We might consider the implications of this practice’s braiding together—through both contract and extant matter, through abstraction and concretion—the instance of the institution with the longue durée of slavery’s worldmaking aftermaths, a move that enables Rowland’s work to “transversally connect with and through [Black Radical] movements elsewhere, and to materialize those movements within the space of art as a concrete rather than gestural politics.”26

To borrow still further down that line from Ciarán Finlayson, it is a function of Rowland’s insistence on the docket, the jurisprudential precisions of the written contract, that links post-Emancipatory racial logics to their roots in pre–Civil War orders of slavery, as was materialized in Rowland’s pathbreaking debut exhibition “91020000” at Artist’s Space in 2016. Thus, in Dia’s instance, Rowland’s Increase (2024)27 sounds the awful consonance of Black infant mortality’s comparable rate of death in the present to that obtaining under chattel slavery:

Black infants in America are now more than twice as likely to die as white infants—11.3 per 1,000 black babies, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 white babies, according to the most recent government data—a racial disparity that is actually wider than in 1850, 15 years before the end of slavery, when most black women were considered chattel.28

Finlayson observes of this consonance that Rowland’s works “bear witness to abolition as the emancipation of capital and testify to the purported freedom on the far side of Jubilee as the dominion of what DuBois would call ‘dictatorship of property.’”29 So just as McQueen’s operative mechanism in Bass conscripts, so Rowland’s contractually architected relationship between extant object (or, more colloquially, ready-made) and art institution collapses aesthetic autonomy (and its values) into a structure and scene of contracted labor wherein personhood, propriety, and property are indivisible from white supremacy’s submarine architectures of enclosure and expropriation, wherein that which has been “purchased,” rented, or otherwise obtained and redeployed as art is committed to a program of derelict use, to a mutually agreed upon contractual promise of depreciation, degradation, deprecation of value, “raising the question as to what it might mean for these objects, completely unadorned, to be works of contemporary art only insofar as they are straightforwardly useful objects or historical artifacts.”30 To follow Finlayson, we might say: these “works” work. This simple fact enacts a kind of contagion consonant with McQueen’s bass-driven drift, since it extends to every object existent under the edifice of racial slavery’s ongoing aftermath … This is the nature of our (un)common (under)common entanglement, and it describes a space with no wholly separable straight lines.

***

“Properties” begins multiply. It begins with Estate—sited at the museum’s ticket desk—listing an inventory of literal properties, enumerating Schlumberger’s foundational contribution of oil wealth’s returns to the erection of an institution with canonical influence over common conceptions of the anti-normative possibilities of conceptual art. It equally begins with Rowland’s plot, which we might venture to say brings “exhibition” online: wherein Rowland’s work triggers the institution’s need to show what cannot be held, what cannot be owned, such need thus engendering commitment to the successive depreciation of its value(s). “Properties” does this in an institution whose single unit of measure—the day—is relentlessly interminably assailed by the ecological and neo-imperial depredations of an industry that bequeaths to the Dia Foundation its ground, its common forms of access, its public face. Here, there is echo of Gladman (2018) in Moten (2013):

There is an ethics of the cut, of contestation, that I have tried to honor and illuminate because it instantiates and articulates another way of living in the world, a black way of living together in the other world we are constantly making in and out of this world, in the alternative planetarity that the intramural, internally differentiated presence—the (sur)real presence—of blackness serially brings online as persistent aeration, the incessant turning over of the ground beneath our feet that is the indispensable preparation for the radical overturning of the ground that we are under.31

Can we perhaps now hear Rowland’s underproduction and McQueen’s infratones in a certain synchrony?

The first sight line in “Properties” is of/toward this Plot—a distant contract, but simultaneously a verb, a noun, an activity, a structure, a plan, the inner logic of a (melo)drama, the hydraulic32 mechanism that enables whiteness to metabolize its violence and regulate itself. To reach this plot one must first pass through a voided white vestibular space in which Rowland’s short publication stands in stacks as an open invitation to study. In pondering this invitation to reckon with one’s imbrication in this scene, this str(ict/u)ture, this plot, I am moved to ask: Can an upturned pan speak history’s scouring back into an emptied space? Can the sequence of five scythes that constitute Commissary (2024)33 sing in an interminable round loudly enough that we might sense their volatility? Can these rusted scimitar blades speak to the silence that surrounds them—can they cut industry and its initiating iniquities together in a necrotic embrace, one that sounds the threshed textures of this harvest that counterposes Increase and Commissary as two poles within Rowland’s magnetic field, in a gallery where their four works are arrayed at points north, south, east, and west—marking the totality of its and our social field?

Cameron Rowland, “Properties,” 2024, Dia Beacon. Installation view.

Can we reckon with the integration of these objects—objects which issued from the regularizing and repressive architectures of slavery and its aftermath—as precedent to the industrial modernity that gave us ceramic fountains and specific objects as matter for thought of the notion of transcendence? Can we attend to the manner in which their exhumation orients us toward a horizon beyond art (and its many precincts),34 and toward the structures of a world that invents leisure35 to manage the necropolitical eviscerations that its malignant lifeworlds depend upon?

It would be my contention that these questions concern us so much more than they do these objects on display. Given that for those myriad subaltern communities marked as structurally disposable, as incapable of (democratic) rights and the (responsible) exercise of freedom, “the fascism which liberal modernity and civil society have always required has never abided by this order’s mendacious separation of the political from the aesthetic,”36 how could one expect an art keyed to the operation of these structures, or grounded in the historical praxis of these communities, to conform to the artifice of such notionally separable strictures as those that divide aesthetics from politics, form from content, present from past, living from dead?37

If we even provisionally understand, as so many of those engaged in Black studies do, that “genocide, now as before, is an aesthetic project,” and that therefore the luster, integrity, probity, and solicitousness of culture serves precisely to veil and abet its perpetual practice of genocide as economic rationale, as engine of state formation, as regeneration of “growth,” then which aesthetic act can be materially uncoupled from the political arrangements of subjection that underwrite artistic “freedom”? Or, better still, in the words of Rizvana Bradley, “how do we survive the aesthetic regime that carves and encloses the very shape of our question?”38 Renee Gladman again:

I was looking into the moss growing between the bricks laid out in front of the door, looking into the moss as its own space, its doing beyond making a border, and the green coming back after such a long winter, bright but also mourning—the sun bearing down on it, the clouds blocking the sun, the human eyes glaring—and found, within, spaces that bordered some infinite writing about process and thought, some unending burrowing, some endless death and reach, some constant holding in place, Kristin Prevallet’s “the poem is a state both of mind and landscape,” and our books burrowing inside our drawings, the lines holding the brick unyielding.39

Steve McQueen, Bass (detail), 2024. © Steve McQueen. Photo: Don Stahl.

Faced with the impulse to break out of this bind, perhaps we might return to McQueen’s Exodus (1992–97), freshly on display at Dia Chelsea, a looped Super 8 film transferred to digital video and sited at the center of the first of his two galleries. It is a film in which, following the line of Tavia Nyong’o, “the blackness interpolated between cinema’s vaunted ‘twenty-four frames a second’” can be read between the weaving motion of these two Black men, echoing back Bass’s errant and digressive iterations as another order of blackened motion that brings dissonant difference into simultaneous articulation.40

If I might follow their lead, and depart momentarily from the order of propriety, it seems to me that in McQueen’s Sunshine State (2022), the twinned and inverted two-channel structure of simultaneous erasures of Al Jolson’s skin enacted in the film, whether into shadow under the glistening gleam of boot black, or into the irradiating halations of white “in the negative,” hail back not merely to the hydraulics of anti-Blackness, and to its generative negrophiliac dimensions, but forward to Cindy Sherman’s untitled and aborted “self-portrait” in blackface, and to Bruce Nauman’s “self-erasure” in his own self-assigned experiment with racial abnegation in Flesh to White to Black to Flesh (1968), an action resurfaced obliquely in Pfeiffer’s Artists on Artists talk in October of last year.

In the involuted echo of these “experimental” iterations of artistic freedom, McQueen’s Sunshine State unearths an antinomy of drastic disequilibrium in which opposition (of black to white, front to back) and equality (in the simultaneous identity of twin frames) are discomposed by the desirous depths of a whiteness that cannot separate the violence of consumption from the practice of affiliation that always incorporates, destroys, disfigures the difference it ostensibly seeks to celebrate.41 Sunshine State shows that within this twinned figure lurks the law of the singular, and its perpetual order of exception. Whiteness must first confront the reality of this need, this profound desire for possessive mastery before learning to desire, to move, to want otherwise. It must want Exodus as leave-taking beyond every register of possession. McQueen’s incantations of the work’s title in Sunshine State seem to articulate this training in the recursive structure of a chant that stages repetition as a programmatic transformation of the self’s relationship to meaning, through the iterations of memory.

In the neighboring gallery, Exodus’s concentric loop of surveilled entry and Black motion sits at the core of a panoply of photographic prints displaying luminous buds, flowers, stalks, fronds, leaves, stems, meshed webs, and tendrilled networks of rhizomatic Grenadian plant life that animates McQueen’s concentric array in a pallid gallery. The prints’ alternating assembly of longitudinal and vertical frames already figures seriality’s constitutive and repressed dependence on the irregular as an eruption that calls for the brutal impositions of order. We might recall here a short line from Moten’s 2015 lecture “Blackness and Nonperformance”: “Forms are reclaimed by the informality that precedes them.”42

McQueen’s prints describe a chromatic fullness of rusted reds and ebullient pinks, ringing the mute tones of the gallery with magenta-tinged depths, submarine greens, and deep black shades, which together fashion a filmic strip of hues that wend a musical structure across the patinaed walls and against the starched parchment of the gallery’s grey floor. The bricked enclosures of Dia’s arches mirror the flat plane of its grey floors and walls, making of the photographs a sinuous weave of Grenadian plant life that articulates a protuberant efflorescence, measured and restrained only by the white enclosures of the picture’s frames. Perhaps this is the (ef)florescence with which Moten was concerned in our epigrammatic opening?

In Exodus, McQueen’s twin Black men march the antenna-shaped fronds of their two potted plants through the bustling Brownian motion of London streets at a rhythm of two-by-two-by-two-by-two, their upright and elegant peregrinations beneath the nodding brims of porkpie hats and macintoshed coats rhyming, and bending white patrician codes to insistently queer Caribbean rhythms. They weave, they thread, they warp and bend—they miscegenate:

And I had found in reading a way to draw lines from the earth and make an outline around my sitting at this table or walking the streets of any place, any large or small city, any countryside, any emptied forgotten place, any place transitioning, taking on multiple identities, blaring them at once, and this was all architecture, all the reading I had done. Lyn Hejinian’s “the open mouths of people,” her “weather and air drawn to us,” to say, “landscape is a moment in time.” I’d found in my walking the expanse of several places through which I stopped repeatedly, I stopped in time and without time, I stood at the thresholds of doors, at the throats of caves; I pulled windows from collapsed walls, and grabbed a book to hold up the city, the barn, the balcony, and this was reading … Reading aggregated layers, with luminous lines running between, and each line was a moment in someone, where the body stood up and walked into a book, a drawing, a squat structure of doors, a tower perched on a hill, into the water, and each line was the writing back of language, its response, its figurations, and all this queering at the corners, putting corners everywhere, even on top of one another. And I found in my narrative these other narratives that opened under water, that glowed in deepest night, that you could read without alarm, that were blown-out geometries, maps, that were textiles hanging from the ceiling, calendula underground, always having something to do with bodies, moving through other bodies.43

Steve McQueen, Bass, on view at Dia Beacon until May 26, 2025. Cameron Rowland, “Properties,” on view at Dia Beacon until October 20, 2025. Steve McQueen, “Steve McQueen,” on view at Dia Chelsea until July 19, 2025.

Fred Moten, “Blackness and Nonperformance,” lecture, Museum of Modern Art, September 25, 2015, YouTube video →.

The writing in this essay has been deeply informed and influenced by Anthony Huberman’s Cooper Union IDS lecture “Bang on a Can,” February 8, 2022 →; and, in turn, by the work of Fred Moten. Neither party bears responsibility for any of the many flaws that follow. With sincere thanks to Leslie Hewitt and Omar Berrada for organizing such a rich and inspirational series of convenings over the years.

Underproduction (2024). Overturned pot, 18 × 21 × 16 inches. Slaves outnumbered owners on the plantation. Slaves were an inherent risk to the plantation. Owners banned slaves from meeting with one another. Slaves met anyway. An overturned pot placed at the door of the meeting blocked the sound of the gathering. The overturned pot protected meetings from the slave patrol. The meetings were negations of the plantation logic of production.

Saidiya V. Hartman and Frank B. Wilderson III, “The Position of the Unthought,” Qui Parle 13, no. 2 (Spring–Summer 2003).

Marina Vishmidt, “A Self-Relating Negativity: Where Infrastructure and Critique Meet,” in Broken Relations: Infrastructure, Aesthetics and Critique ed. Martin Beck et al. (Spector Books, 2022), 40.

See Caitlin C. Rosenthal, “How Slavery Inspired Modern Business Management,” Boston Review, August 20, 2018 →.

See Saidiya Hartman, “A Note on Method,” in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (W. W. Norton, 2019).

Bass features the performances of Steve McQueen as director, and Marcus Miller, Aston Barrett Jr., Mamadou Kouyaté, and Laura-Simone Martin on the bass.

“On the ground, under it, in the break between deferred advent and premature closure, natality’s differential presence and afterlife’s profligate singularities, social vision, blurred with the enthusiasm of surreal presence and unreal time, anticipates and discomposes the harsh glare of clear-eyed, supposedly impossibly originary correction, where enlightenment and darkness, blindness and insight, invisibility and hypervisibility converge in the open obscurity of a field of study and a line of flight.” Moten, “Blackness and Nonperformance.”

See Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” in “On the Archaeologies of Black Memory,” special issue, small axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12, no. 2 (2008).

See Saidiya Hartman, “The Belly of the World: A Note on Black Women’s Labors,” in “Black Women’s Labor: Economics, Culture, and Politics,” special issue, Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society 18, no. 1 (January–March 2016).

Tina Campt, “Introduction: Listening to Images—An Exercise in Counterintuition,” in Listening to Images (Duke University Press, 2017), 7.

Note the subtle interanimation and syncopation of Pfeiffer’s multiple shadows with Bruce Nauman’s rhythmic, pathological cascade of falls in Bouncing in the Corner, No. 1 (1968) →, a work made in the same year that Nauman assumed blackface in Flesh to White to Black to Flesh (1968) →. See “Paul Pfeiffer on Bruce Nauman,” YouTube video, posted October 9, 2024, by Dia Art Foundation →.

See “Leslie Hewitt,” June 24, 2022–June 4, 2023, Dia Bridgehampton; “Tony Cokes,” June 23, 2023–May 27, 2024, Dia Bridgehampton; “Delcy Morelos: El abrazo,” October 5, 2023–July 20, 2024, Dia Chelsea; “stanley brouwn,” April 15, 2023–2025, Dia Beacon; “Felix Gonzalez-Torres,” April 5, 2024–Spring 2025, Dia Beacon; “On Kawara,” long-term view, Dia Beacon; “Senga Nengudi,” long-term view, Dia Beacon.

“Reinhardt reads blackness at sight, as held merely within the play of absence and presence. He is blind to the articulated combination of absence and presence in black that is in his face, as his work, his own production, as well as in the particular form of Taylor. Mad, in a self-imposed absence of (his own) work, Reinhardt gets read a lecture he must never have forgotten, though, alas, he was only to survive so short a time.” Fred Moten, “The Case of Blackness,” Criticism 50, no. 2 (Spring 2008): 190 →.

Renee Gladman, “Untitled (Environments),” e-flux journal, no. 92 (June 2018) →.

Plot (2024). Easement, one acre in Beacon, New York. Black people were prohibited from being buried in cemeteries. These prohibitions were applied to both free and enslaved Black people, in both the North and the South. They were meant to make the degradation of Blackness permanent. Black people were buried in unmarked slave plots and unregistered Black burial grounds. For many Black people these Black mass graves were extensions of Black life. As Sylvia Wynter describes, Black mass graves were a point of connection to the “permanent future” and the “historical life of the group.” As Wynter writes of the provision grounds where slaves grew their own food, the burial plot was also “an area of experience which reinvented and therefore perpetuated an alternative world view, an alternative consciousness to that of the plantation. This world view was marginalized by the plantation but never destroyed. In relation to the plot, the slave lived in a society partly created as an adjunct to the market, partly as an end in itself.” Black people used funerals and burial grounds to plot escape and rebellion. In response, laws banning slave funerals and grave markers were passed throughout the Caribbean and the North American colonies. As former slave John Bates said, masters who prohibited slave funerals would “jes’ bury dem like a cow or a hoss, jes’ dig de hole and roll ’em in it and cover ’em up.” Unmarked Black burials are frequently disinterred during real estate development. This has been the case for numerous burial grounds in New York State and throughout the country. Construction frequently continues despite these “discoveries.” In 1790, the US Census recorded nearly as many slaves in New York State as in Georgia. The land that Dia Art Foundation currently owns in Beacon, New York was owned by slave owners and slave traders from 1683 until the abolition of slavery in New York in 1827. The easement between Dia Art Foundation and Plot Inc. conveys the rights to a one-acre section of the institution’s property to Plot Inc. for the purpose of protecting the graves of enslaved people who may have been buried there. This burial ground easement runs with the land and requires Dia and all future owners to relinquish the rights to use, disturb, or develop this section of the property. The plot will remain unmarked. It will degrade the value of the institution’s property. It challenges the assumed absence of Black burials on sites of enslavement by assuming their presence. See →.

This mooted trio comprises both Plot as contract framed on the wall, Plot as easement sited in degenerative growth on Dia’s grounds, and Estate (2024). Per the artist: “Estate (2024): Dia Art Foundation Real Estate, 1974–2024. Books, $10 each. Schlumberger Limited, established in 1926, is the largest oilfield services company in the world. Descendants of founder Conrad Schlumberger used their shares in the company to create the Dia Art Foundation. Schlumberger Limited was the primary source of funds for the first decade of the institution. During this period, Dia purchased the majority of the fifty-nine real estate properties it has owned during the past fifty years. The properties were purchased for artists, for artworks, for offices, for exhibition spaces, and as rentals. Many of these properties were given away. Many were sold at a high rate of return. A number continue to function as rental properties, which generate over one million dollars of annual income for the institution. Dia does not retain information on the history of these properties prior to the twentieth century.”

“If slavery persists as an issue in the political life of black America, it is not because of an antiquarian obsession with bygone days or the burden of a too-long memory, but because black lives are still imperilled and devalued by a racial calculus and a political arithmetic that were entrenched centuries ago. This is the afterlife of slavery—skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment. I, too, am the afterlife of slavery.” Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2007), 7.

See Kathryn Yusoff, “Mine as Paradigm,” e-flux Architecture, June 2021 →.

Gladman, “Untitled (Environments).”

The intricacies of this dimension of Rowland’s practice, and the deeper analytical, political, and artistic implications of them, are substantive and wide-reaching, deserving of a greater level of sustained attention than this register of response can realistically or ethically accommodate. See Eric Golo Stone, “Legal Implications: Cameron Rowland’s Rental Contract,” October, no. 164 (Spring 2018); and Zoé Samudzi, “Rethinking Reparations,” Art in America, Fall 2023.

See also Jack Whitten, Atopolis: For Édouard Glissant (2014). Acrylic on canvas, eight panels, overall 124 ½ × 248 ½ inches →.

Vishmidt, “A Self-Relating Negativity,” 30.

Vishmidt, “A Self-Relating Negativity,” 31–32.

Increase (2024). Bed frame, 46 × 42 × 78 inches. Under slave law, partus sequitur ventrem stipulated that the “child follows the belly.” When slave owners bought Black women, they also purchased the rights to what owners termed “all her future increase.” Saidiya Hartman describes the centrality of this principle to the system of racial slavery: “The work of sex and procreation was the chief motor for reproducing the material, social, and symbolic relations of slavery. The value accrued through reproductive labor was brutally apparent to the enslaved who protested bitterly against being bred like cattle and oxen.” This status was constructed to last forever. What Jennifer Morgan names as “the value of a reproducing labor force” has ordered the continuity of this sexual violence. Domestic work has been a principal vector for its preservation. Live-in workers have been made perpetually available to their employers. Refusals of this availability are criminalized. Christina Sharpe makes clear that “living in/the wake of slavery is living ‘the afterlife of property’ and living the afterlife of partus sequitur ventrem (that which is brought forth follows the womb), in which the Black child inherits the non/status, the non/being of the mother. That inheritance of a non/status is everywhere apparent now in the ongoing criminalization of Black women and children.” Non/being constitutes a position whose modalities of life and death are simultaneously structured by and unrecognizable to the capture of ownership. As Hartman writes, “The forms of care, intimacy, and sustenance exploited by racial capitalism, most importantly, are not reducible to or exhausted by it. These labors cannot be assimilated to the template or grid of the black worker, but instead nourish the latent text of the fugitive. They enable those ‘who were never meant to survive’ to sometimes do just that.” This fugitivity is an inherent threat to the value of increase. See →.

Linda Villarosa, “Why America’s Black Mothers and Babies Are in a Life-or-Death Crisis,” New York Times Magazine, April 11, 2018 →.

Ciarán Finlayson, “Perpetual Slavery,” Parse Journal, 2019 →. Emphasis mine. See also Ciarán Finlayson, Perpetual Slavery (Floating Opera Press, 2023).

Finlayson, “Perpetual Slavery.”

Fred Moten, “Blackness and Nothingness: Mysticism in the Flesh,” South Atlantic Quarterly 112, no. 4 (Fall 2013): 778–79.

See Frank B. Wilderson III, Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of US Antagonisms (Duke University Press, 2010).

Commissary (2024). Scythes 59.5 × 52 × 16 inches. Rental Sharecropping was debt peonage. It was instituted to replace slave labor. It operated in explicit violation of the Thirteenth Amendment’s stated ban on involuntary servitude. Sharecropping contracts were designed to keep Black people bound to the land, which their labor made valuable. Violations of the contract included leaving the plantation without permission; being loud, disorderly, drunk, or disobedient; having an “offensive weapon”; and misusing the tools. Violations were grounds for dismissal, eviction, and forfeiture of the share. In addition to cultivating the land, these contracts could include obligations to do the washing “and all other necessary house work” for the landlord’s family. Sharecroppers were forced to buy food, clothes, tools, and other necessities on credit from the landlord’s general store, also called the commissary. The commissary charged up to 70 percent interest. Debts were deducted from the cropper’s share. The contract and the commissary kept sharecroppers in perpetual debt. W. E. B. Du Bois describes the terms of this labor as “a wage approximating as nearly as possible slavery conditions, in order to restore capital lost in the war.” Many sharecroppers were former slaves. Many sharecroppers were the children of former slaves. Slaves used scythes as tools of rebellion in Henrico County, Virginia, in 1800; in Southampton County, Virginia, in 1831; and in Coffeeville, Mississippi, in 1858. In violation of their contracts, croppers armed themselves as well. The tools of perpetual debt were also the tools of Black riot.

See Stefano Harney’s remarks as part of Nitasha Dhillon and Amin Hussein’s panel “Strike MoMA: A Conversation with Sandy Grande, Stefano Harney, Fred Moten, Jasbir Puar, and Dylan Rodriguez,” beginning at forty-three minutes in the following video, and note in particular his deployment of the term “precinct” at 43:28 →.

See Simon Gikandi, Slavery and the Culture of Taste (Princeton University Press, 2011).

Rizvana Bradley and Denise Ferreira da Silva, “Four Theses on Aesthetics,” e-flux journal, no. 120 (September 2021) →.

Rizvana Bradley, “The Difficulty of Black Women (A Response),” Artforum, December 20, 2022 →. See also Rizvana Bradley, “The Black Residuum, or That Which Remains,” chap. 4 in Anteaesthetics: Black Aesthesis and the Critique of Form (Stanford University Press, 2023).

Bradley and da Silva, “Four Theses on Aesthetics.”

Gladman, “Untitled (Environments).”

Tavia Nyongo’o, “Habeas Ficta: Fictive Ethnicity, Affecting Representations, and Slaves on Screen,” in Migrating the Black Body, ed. Leigh Raiford and Heike Raphael-Hernandez (University of Washington Press, 2017), 288.

We would do well to think of the Palestinian people here, and of the forcible suppression of Arab speech at the US Democratic National Convention in August 2024.

Moten, “Blackness and Nonperformance.”

Gladman, “Untitled (Environments).”

My sincere thanks to Solveig, Rhea, Tom, Anthony, Ben, and Aaron for their patience and generous support. Thanks to the artists for the special dispensations in the video piece. Lastly, and most emphatically, my thanks to Emily Markert and the team at Dia Beacon, who spent their weekend hunting down echoes in the galleries.